Constitutional Points of Order in the Senate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

Committee Handbook New Mexico Legislature

COMMITTEE HANDBOOK for the NEW MEXICO LEGISLATURE New Mexico Legislative Council Service Santa Fe, New Mexico 2012 REVISION prepared by: The New Mexico Legislative Council Service 411 State Capitol Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 (505) 986-4600 www.nmlegis.gov 202.190198 PREFACE Someone once defined a committee as a collection of people who individually believe that something must be done and who collectively decide that nothing can be done. Whether or not this definition has merit, it is difficult to imagine the work of a legislative body being accomplished without reliance upon the committee system. Every session, American legislative bodies are faced with thousands of bills, resolutions and memorials upon which to act. Meaningful deliberation on each of these measures by the entire legislative body is not possible. Therefore, the job must be broken up and distributed among the "miniature legislatures" called standing or substantive committees. In New Mexico, where the constitution confines legislative action to a specified number of calendar days, the work of such committees assumes even greater importance. Because the role of committees is vital to the legislative process, it is necessary for their efficient operation that individual members of the senate and house and their staffs understand committee functioning and procedure, as well as their own roles on the committees. For this reason, the legislative council service published in 1963 the first Committee Handbook for New Mexico legislators. This publication is the sixth revision of that document. i The Committee Handbook is intended to be used as a guide and working tool for committee chairs, vice chairs, members and staff. -

Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2005 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adrian Vermeule, "Absolute Voting Rules" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 257, 2005). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 257 (2D SERIES) Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2005 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=791724 Absolute Voting Rules Adrian Vermeule* The theory of voting rules developed in law, political science, and economics typically compares simple majority rule with alternatives, such as various types of supermajority rules1 and submajority rules.2 There is another critical dimension to these questions, however. Consider the following puzzles: $ In the United States Congress, the votes of a majority of those present and voting are necessary to approve a law.3 In the legislatures of California and Minnesota,4 however, the votes of a majority of all elected members are required. -

A Guide to Parliamentary Procedure for New York City Community Boards

CITY OF NEW YORK MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, MAYOR A GUIDE TO PARLIAMENTARY PROCEDURE FOR NEW YORK CITY COMMUNITY BOARDS Mayor's Community Assistance Unit Patrick J. Brennan, Commissioner r. 2003/6.16.2006 Page 2 A Guide to Parliamentary Procedure for NYC Community Boards Mayor's Community Assistance Unit INTRODUCTION "The holding of assemblies of the elders, fighting men, or people of a tribe, community, or city to make decisions or render opinion on important matters is doubtless a custom older than history," notes Robert's Rules of Order, Newly Revised. This led to the need for rules of procedures to organize those assemblies. Throughout history, the writers of parliamentary procedure recognized that a membership meeting should be a place where different people of a community gather to debate openly and resolve issues of common concerns, the importance of conducting meetings in a democratic manner, and the need to protect the rights of individuals, groups, and the entire assembly. Parliamentary procedure originally referred to the customs and rules used by the English Parliament to conduct its meetings and to dispose of its issues. Some of the unusual terms used today attest to that connection -- such terms as "Lay On The Table" or "I Call The Previous Question." In America, General Henry Martyn Robert (1837-1923), a U.S. Army engineering officer was active in civic and educational works and church organizations. After presiding over a meeting, he wrote "But with the plunge went the determination that I would never attend another meeting until I knew something of... parliamentary law." After many years of study and work, the first edition of Robert's manual was published on February 19, 1876 under the title, Robert's Rules of Order. -

Points of Order; Parliamentary Inquiries

Points of Order; Parliamentary Inquiries A. POINTS OF ORDER § 1. In General; Form § 2. Role of the Chair § 3. Reserving Points of Order § 4. Time to Raise Points of Order § 5. Ð Against Bills and Resolutions § 6. Ð Against Amendments § 7. Application to Particular Questions; Grounds § 8. Relation to Other Business § 9. Debate on Points of Order; Burden of Proof § 10. Waiver of Points of Order § 11. Withdrawal of Points of Order § 12. Appeals B. PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRIES § 13. In General; Recognition § 14. Subjects of Inquiry § 15. Timeliness of Inquiry § 16. As Related to Other Business Research References 5 Hinds §§ 6863±6975 8 Cannon §§ 3427±3458 Manual §§ 627, 637, 861b, 865 A. Points of Order § 1. In General; Form Generally A point of order is in effect an objection that the pending matter or proceeding is in violation of a rule of the House. (Grounds for point of order, see § 7, infra.) Any Member (or any Delegate) may make a point of order. 6 Cannon § 240. Although there have been rare instances in which the Speaker has insisted that the point of order be reduced to writing (5 633 § 1 HOUSE PRACTICE Hinds § 6865), the customary practice is for the Member to rise and address the Chair: MEMBER: Mr. Speaker (or Mr. Chairman), I make a point of order against the [amendment, section, paragraph]. CHAIR: The Chair will hear the gentleman. It is appropriate for the Chair to determine whether the point of order is being raised under a particular rule of the House. The objecting Member should identify the particular rule that is the basis for his point of order. -

The Legislative Process on the House Floor: an Introduction

The Legislative Process on the House Floor: An Introduction Updated May 20, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov 95-563 The Legislative Process on the House Floor: An Introduction Summary The daily order of business on the floor of the House of Representatives is governed by standing rules that make certain matters and actions privileged for consideration. On a day-to-day basis, however, the House can also decide to grant individual bills privileged access to the floor, using one of several parliamentary mechanisms. The standing rules of the House include several different parliamentary mechanisms that the body may use to act on bills and resolutions. Which of these will be employed in a given instance usually depends on the extent to which Members want to debate and amend the legislation. In general, all of the procedures of the House permit a majority of Members to work their will without excessive delay. The House considers most legislation by motions to suspend the rules, with limited debate and no floor amendments, with the support of at least two-thirds of the Members voting. Occasionally, the House will choose to consider a measure on the floor by the unanimous consent of Members. The Rules Committee is instrumental in recommending procedures for considering major bills and may propose restrictions on the floor amendments that Members can offer or bar them altogether. Many major bills are first considered in Committee of the Whole before being passed by a simple majority vote of the House. The Committee of the Whole is governed by more flexible procedures than the basic rules of the House, under which a majority can vote to pass a bill after only one hour of debate and with no floor amendments. -

Role of the Chair and Decorum Presentation

Role of the Chair, Decorum, and More By Felix Rivera 2.30.020 – Presiding Officer • A. The chair of the assembly shall be the presiding officer of the assembly. • B. The vice-chair of the assembly shall be the presiding officer of the assembly in the case of unavailability of the chair. • C. The presiding officer shall be addressed as "Chair." • D. The presiding officer shall be a member of the assembly with all of the power and duties of that office. Section 4.04 – Presiding officer, meetings and procedures • (a) The assembly shall elect annually from its membership a presiding officer known as "chair." The chair serves at the pleasure of the assembly. • (b) The assembly shall meet in regular session at least twice each month. The mayor, the chair of the assembly, or five assembly members may call special meetings. Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised 11th Edition, pages 449-450 • 1. To open and call the meeting to order • 2. To announce in proper sequence the business that come before the assembly • 3. To recognize members who are entitled to the floor • 4. To state and to put to vote all questions that legitimately come before the assembly • 5. To protect the assembly from obviously dilatory motions • 6. To enforce the rules relating to debate and those relating to order and decorum Robert’s Rules of Order Continued, pages 449-450 • 7. To expedite business in every way compatible with the rights of the members • 8. To decide all questions of order, subject to appeal • 9. -

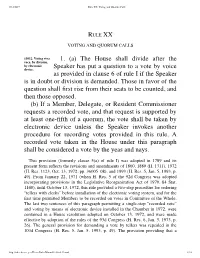

Rule XX- Voting and Quorum Calls

9/12/2017 Rule XX: Voting and Quorum Calls RULE XX VOTING AND QUORUM CALLS §1012. Voting viva 1. (a) The House shall divide after the voce, by division, by electronic Speaker has put a question to a vote by voice device. as provided in clause 6 of rule I if the Speaker is in doubt or division is demanded. Those in favor of the question shall first rise from their seats to be counted, and then those opposed. (b) If a Member, Delegate, or Resident Commissioner requests a recorded vote, and that request is supported by at least one-fifth of a quorum, the vote shall be taken by electronic device unless the Speaker invokes another procedure for recording votes provided in this rule. A recorded vote taken in the House under this paragraph shall be considered a vote by the yeas and nays. This provision (formerly clause 5(a) of rule I) was adopted in 1789 and its present form reflects the revisions and amendments of 1860, 1880 (II, 1311), 1972 (H. Res. 1123, Oct. 13, 1972, pp. 36005–08), and 1993 (H. Res. 5, Jan. 5, 1993, p. 49). From January 22, 1971 (when H. Res. 5 of the 92d Congress was adopted incorporating provisions in the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, 84 Stat. 1140), until October 13, 1972, this rule provided a two-step procedure for ordering “tellers with clerks” before installation of the electronic voting system, and for the first time permitted Members to be recorded on votes in Committee of the Whole. The last two sentences of this paragraph permitting a single-step “recorded vote” and voting by means of electronic device installed in the Chamber in 1972, were contained in a House resolution adopted on October 13, 1972, and were made effective by adoption of the rules of the 93d Congress (H. -

Robert's Rules of Order

Robert’s Rules of Order: How to Effectively Run a Meeting What is Robert’s Rules of Order? • Most widely used manual of “parliamentary procedure” for non-legislative organizations • Used as a means to organize a meeting for: • Church groups • Professional societies • School boards • Associations • Etc. Purpose of Robert’s Rules of Order • Ensure “majority rule” • Protect rights of minority & absentee votes • Provide order and fairness in decisions made • Expedite meetings • All members have equal rights and privilege • Provides checks and balances amongst hierarchy of positions in meetings Components of Robert’s Rules of Order • Quorum must be present for business to occur. Quorum is the minimum number of members of a group that must be present at any meeting, to ensure that enough voices are heard for the decisions made during that meeting to be valid • Agenda created for meeting • Motions – formal proposal for action to be taken on certain topic by organization’s membership Let’s Put It All Together… Commonly Asked Questions of Robert’s Rules of Order 1. Is it true that the president can vote only to break a tie? a) No, it is not true. If the president is a member of the voting body, he or she has exactly the same rights and privileges as all other members have, including the right to make motions, to speak in debate, and to vote on all questions.. However, the impartiality required of the presiding officer of any other type of assembly (especially a large one) precludes exercising the rights to make motions or speak in debate while presiding, and also requires refraining from voting except (i) when the vote is by ballot, or (ii) whenever his or her vote will affect the result. -

Robert's Rules of Order As Used by the General Tribal Council Voting

Robert’s Rules of Order As Used by the General Tribal Council Voting Majority Vote - used in most instances and requires a simple majority of the members voting, excluding those who choose to abstain. The abstentions are asked for to complete the record, not to include them in the count. Two-Thirds Vote - used to overturn a previous action as identified in the Ten Day Notice Policy. Requires two-thirds of those voting to take action, excluding those who choose to abstain. The total number of votes, divided by three, multiplied times two. Fragments are included in the ‘yes’ votes as that is where two-thirds of the vote lies. Note: an action of the membership to overturn a prior action taken at a meeting which was concluded by the Business Committee on behalf of the General Tribal Council, because no quorum was met, falls within the Ten Day Notice Policy requirements. Tie Votes - in the event of a tie, the Chairperson can vote. A tie is identified in Robert’s Rules of Order as an occasion where if the Chair casts a vote, a different outcome will result. The Constitution identifies that the Chair votes “only in the case of a tie.” This has been identified to limit the ability of the Chair to vote to break a tie vote. In the case of a two- thirds vote, where it would change the results of the vote. Point of Order A point of order arises when a member who has the floor is not talking about the subject matter on the agenda before the membership at that time in the meeting. -

Chapter 1 Adjournment

Chapter 1 Adjournment A. GENERALLY; ADJOURNMENTS OF THREE DAYS OR LESS § 1. In General § 2. Adjournment Motions and Requests; Forms § 3. When in Order; Precedence and Privilege of Motion § 4. In Committee of the Whole § 5. Who May Offer Motion; Recognition § 6. Debate on Motion; Amendments § 7. Voting § 8. Quorum Requirements § 9. Dilatory Motions; Repetition of Motion B. ADJOURNMENTS FOR MORE THAN THREE DAYS § 10. In General; Resolutions § 11. Privilege of Resolution § 12. August Recess C. ADJOURNMENT SINE DIE § 13. In General; Resolutions § 14. Procedure at Adjournment; Motions Research References U.S. Const. art. I, § 5 5 Hinds §§ 5359–5388 8 Cannon §§ 2641–2648 Manual §§ 82–84, 911–913 1 VerDate 29-JUL-99 20:28 Mar 20, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00010 Fmt 2574 Sfmt 2574 C:\PRACTICE\DOCS\MHP.001 PARL1 PsN: PARL1 §1 HOUSE PRACTICE A. Generally; Adjournments of Three Days or Less § 1. In General Types of Adjournments Adjournment procedures in the House are governed by the House rules and by the Constitution. There are: (1) adjournments of three days or less, which are taken pursuant to motion; (2) adjournments of more than three days, which require the consent of the Senate (§ 10, infra); and (3) adjourn- ments sine die, which end each session of a Congress and which require the consent of both Houses. Adjournments of more than three days or sine die are taken pursuant to concurrent resolutions. §§ 10, 13, infra. Adjournment Versus Recess Adjournment is to be distinguished from recess. The House may author- ize a recess under a motion provided in rule XVI clause 4. -

Rules Committee Procedures

Rules Committee Procedures 2012 CONTENTS Senate Rules Committee Process .................................................. Page 3 House Rules Committee Process ................................................... Page 5 ************************************************************* Senate Rules Committee Members – 2012 Lt. Governor Brad Owen, Chair Senator Margarita Prentice, Vice Chair Senator Lisa Brown Senator Curtis King Senator Mike Carrell Senator Adam Kline Senator Steve Conway Senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles Senator Tracey Eide Senator Rosemary McAuliffe Senator Karen Fraser Senator Linda Parlette Senator Nick Harper Senator Cheryl Pflug Senator Mary Haugen Senator Debbie Regala Senator Mike Hewitt Senator Mark Schoesler Senator Karen Keiser Senator Val Stevens Senator Joseph Zarelli ************************************************************* House Rules Committee Members - 2012 Rep. Frank Chopp, Chair Rep. Jan Angel Rep. Jim Moeller Rep. Mike Armstrong Rep. Tina Orwall Rep. Cathy Dahlquist Rep. Eric Pettigrew Rep. Richard DeBolt Rep. Tim Probst Rep. Deb Eddy Rep. Ann Rivers Rep. Roger Goodman Rep. Cindy Ryu Rep. Tami Green Rep. Joe Schmick Rep. Bob Hasegawa Rep. Shelly Short Rep. Norm Johnson Rep. Larry Springer Rep. Troy Kelley Rep. Pat Sullivan Rep. Joel Kretz Rep. Kevin Van De Wege Rep. Marcie Maxwell Rep. Judy Warnick SENATE RULES COMMITTEE PROCESS The Rules Committee determines which bills advance to the floor calendar for consideration by the full Senate. There are two calendars in Senate rules. The White Sheet is where bills are sent immediately after being passed out of a standing committee. This is more or less a review calendar. The Green S heet is a consideration calendar made up of bills requested (or "pulled") by Rules members from the White Sheet and is the list of bills eligible to go directly to the floor.