The Mothers: an Exploration of Memory and Secondary Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance This catalog features the novels available for foreign translation and audio rights purchases. SBR Media is owned by Stephanie Phillips Contact: [email protected] Phone: 843.421.7570 SBR Media 3761 Renee Dr. Suite #223 Myrtle Beach, SC 29526 The information in this catalog is accurate as of July 29, 2020. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. SBR Media Catalog of Works .................................................................................................................... 1 Alexis Noelle ............................................................................................................................................... 14 Her Series : Contemporary Suspense ...................................................................................................... 14 Keeping Her ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Deathstalkers MC Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................... 15 Corrupted ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Shattered Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................................. 15 Shattered Innocence ............................................................................................................................ -

Ronnie Dunn and Cracker Barrel Ready to Serve New Music Offering

May 21, 2012 Ronnie Dunn and Cracker Barrel Ready to Serve New Music Offering Sales of Exclusive CD Ronnie Dunn — Special Edition will support Wounded Warrior Project LEBANON, Tenn.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Country music icon Ronnie Dunn's newest solo CD debuts today through the Cracker Barrel Old Country Store® exclusive music program. The CD, Ronnie Dunn — Special Edition, is a powerful collection of 12 songs that Dunn first released in 2011, and includes an additional two previously unreleased bonus tracks. And because Ronnie Dunn and Cracker Barrel support America's military personnel, a portion of the proceeds from sales of this CD will be donated to Wounded Warrior Project™. The CD is available for$11.99 exclusively at all Cracker Barrel locations and online at crackerbarrel.com. Twice named the BMI Country Songwriter of the year, Ronnie Dunn's songs are known for vividly depicting real life as well as profound love. There's a healthy helping of each on this CD with "Cost of Livin'," "Bleed Red," and "Keep on Lovin' You," while "I Love My Country" is richly laden with patriotism. "More than ever before, I feel as though this album gave me a chance to tell my own story through songs that mean a lot to me," says Dunn. "And it's particularly gratifying because, by working with Cracker Barrel, a portion of the CD retail sales will be donated to Wounded Warrior Project. To me, that truly makes this CD a special edition." "We're pleased to work with Ronnie Dunn on a collection of songs we not only think will resonate with our guests, but also will support our nation's Wounded Warriors," said Julie Craig, Cracker Barrel Marketing Manager. -

Brooks and Dunn

BROOKS AND DUNN Brooks & Dunn est un groupe duo de Country Américaine composé de Kix Brooks ( né Léon Eric Brooks III en mai 1955 à Shreveport, Louisiane) et de Ronnie Dunn (né Ronald Gene Dunn, Juin 1, 1953 à Coleman, Texas). Tous deux ont eu une carrière de chanteur compositeur avant la formation du duo. Le duo fait ses débuts en 1991 avec ses quatre premiers singles qui, tous, sont classés numéro un au U.S. Billboard country music charts. Son premier album, Brand New Man, est lancé la même année. Brooks & Dunn ont écrit une quarantaine de singles, dont vingt ont été classés premier. Le duo à enregistré dix albums, deux compilations des « plus grands succès » (greatest-hits), et un album de chansons de Noël. Brooks & Dunn gagnent le prix du CMA du groupe vocal de l’année entre 1992 et 2006, excepté en 2000, lorsque Montgomery gentry a les honneurs cette année là ! En plus, Brooks & Dunn remportent le prix « Entertainer of the Year » en 1996. Deux singles du duo sont nommés, dans le magasine Billboard, Numéro Un de country single de l’année : My Maria » (1996) et « Ain’t Nothing Bout You » (2001). En 2009, le duo annonça sa séparation. Ils firent leur dernier concert le 2 septembre 2010 au Bridgestone Arena de Nashville, Tennessee. Depuis Brooks continue son métier de présentateur radiophonique sur American Country Countdown qu'il exerce depuis 2006, Dunn continue quant à lui une carrière solo chez Arista Records. Association Varoise de Danse Country Albums 1991: Brand New Man 1993: Hard Workin' Man 1994: Waitin' on Sundown 1996: Borderline 1997: The Greatest Hits Collection 1998: If You See Her 1999: Tight Rope 1999: Super Hits 2001: Steers & Stripes 2002: It Won't Be Christmas Without You 2003: Red Dirt Road 2004: The Greatest Hits Collection II 2005: Hillbilly Deluxe 2007: Cowboy Town 2008: Playlist: The Very Best of Brooks & Dunn 2009: #1s… and Then Some Association Varoise de Danse Country . -

Issue 157 Gold Dependent on PD Background? a Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Checking out the Top 100 Most-Played Country Radio Power Gold

September 8, 2009 Issue 157 Gold Dependent On PD Background? A funny thing happened on the way to checking out the Top 100 most-played Country radio Power Gold. I ran the PG list as normal, using Mediabase 24/7 for all CA/Mediabase reporting stations for the two-week period Aug. 23-Sept. 5, 2009. I figure with the start of the fall book just a couple weeks away, it’s a great time to make sure your Power Gold list is polished to a high gloss. After running that list, which appears on Page 6 of this CA Weekly, I decided to run the PG list using the Mediabase 24/7 Custom Report tool for both the “Country PD” and the “Pop- Parr None: KKGO/Los Angeles morning host Shawn Parr served as the background Country PD” filter I’ve run in the past. voice of the Jerry Lewis MDA telethon this past weekend (9/6-7), rubbing Background: In the April 13 CA Weekly (see elbows with everyone from Charro (l) to Wynonna (r). CountryAircheck.com, archives), we ran a comparison of the current music lists from the two sets of programmers. Taylor Turns 10 The “Country PD” list consists of 20 veteran Country radio According to Big Machine, Taylor Swift’s programmers. The “Pop PD” group is 18 current Country radio worldwide album sales have surpassed 10 million programmers who have come to the format for the first time in units, and she’s sold an additional 20 million paid the last year or so. song downloads. -

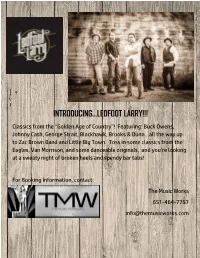

Introducing…Ledfoot Larry!!!

INTRODUCING…LEDFOOT LARRY!!! Classics from the “Golden Age of Country”! Featuring: Buck Owens, Johnny Cash, George Strait, Blackhawk, Brooks & Dunn…all the way up to Zac Brown Band and Little Big Town. Toss in some classics from the Eagles, Van Morrison, and some danceable originals, and you’re looking at a sweaty night of broken heels and spendy bar tabs! For Booking Information, contact: The Music Works 651-464-7757 [email protected] SONG LIST: Red Dirt Road - Brooks & Dunn Dust On The Bottle - David Lee Murphy Some Girls Do - Sawyer Brown Beer Money - Kip Moore Meet In The Middle – Diamond Rio Here's A Quarter - Travis Tritt Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Boondocks - Little Big Town Red Neck Girl - Bellamy Bros. Streets of Bakersfield - Buck Owens Old Alabama - Brad Paisley Chattahoochee - Alan Jackson Chicken Fried - Zac Brown Band Hillbilly Shoes - Montgomery Gentry Wagon Wheel - Old Crow Medicine Show Write This Down - George Strait Fast As You - Dwight Yoakam You Never Even Call Me… - David Allen Coe Goodbye Says It All – Blackhawk Kick A Little - Little Texas Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Be My Baby Tonight – J. Michael Montgomery Pontoon - Little Big Town Killing Time - Clint Black Cadillac Style - Sammy Kershaw Good Hearted Woman – Waylon Jennings Into The Mystic - Van Morrison Unbelievable - Diamond Rio 8 Second Ride - Chris Ledoux Oh Pretty Woman - Roy Orbison The Fireman - George Strait Guitars, Cadillacs - Dwight Yoakam Friends In Low Places – Garth Brooks My Maria - Brooks & Dunn Tequila Sunrise – Eagles Squeezebox - The Who The Shake - Neal McCoy The Race Is On - Sawyer Brown Rodeo – Garth Brooks Real Good Man - Tim McGraw Drink In My Hand - Eric Church Fishin’ In the Dark – Nitty Gritty Dirt Band My Next Broken Heart – Brooks & Dunn Don’t Rock The Jukebox – Alan Jackson From The Horse’s Mouth: “Ledfoot Larry is a very solid country music group. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Request List 619 Songs 01012021

PAT OWENS 3 Doors Down Bill Withers Brothers Osbourne (cont.) Counting Crows Dierks Bentley (cont.) Elvis Presley (cont.) Garth Brooks (cont.) Hank Williams, Jr. Be Like That Ain't No Sunshine Stay A Little Longer Accidentally In Love I Hold On Can't Help Falling In Love Standing Outside the Fire A Country Boy Can Survive Here Without You Big Yellow Taxi Sideways Jailhouse Rock That Summer Family Tradition Kryptonite Billy Currington Bruce Springsteen Long December What Was I Thinking Little Sister To Make You Feel My Love Good Directions Glory Days Mr. Jones Suspicious Minds Two Of A Kind Harry Chapin 4 Non Blondes Must Be Doin' Somethin' Right Rain King Dion That's All Right (Mama) Two Pina Coladas Cat's In The Cradle What's Up (What’s Going On) People Are Crazy Bryan Adams Round Here Runaround Sue Unanswered Prayers Pretty Good At Drinking Beer Heaven Eric Church Hinder 7 Mary 3 Summer of '69 Craig Morgan Dishwalla Drink In My Hand Gary Allan Lips Of An Angel Cumbersome Billy Idol Redneck Yacht Club Counting Blue Cars Jack Daniels Best I Ever Had Rebel Yell Buckcherry That's What I Love About Sundays Round Here Buzz Right Where I Need To Be Hootie and the Blowfish Aaron Lewis Crazy Bitch This Ole Boy The Divinyls Springsteen Smoke Rings In The Dark Hold My Hand Country Boy Billy Joel I Touch Myself Talladega Watching Airplanes Let Her Cry Only The Good Die Young Buffalo Springfield Creed Only Wanna Be With You AC/DC Piano Man For What It's Worth My Sacrifice Dixie Chicks Eric Clapton George Jones Time Shook Me All Night Still Rock And -

Brooks & Dunn Visit Their New Country

(8.9.19) - https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/country/8527035/brooks-dunn-country-music-hall-of-fame-exhibit BROOKS & DUNN VISIT THEIR NEW COUNTRY MUSIC HALL OF FAME EXHIBIT: 'IT'S REALLY MIND BOGGLING' Brooks & Dunn were on hand Thursday evening (Aug. 8), for the unveiling of their new exhibit Brooks & Dunn: Kings of Neon at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville. Ahead of the official exhibit opening on Aug. 9, the country duo addressed a room full of industry peers, friends and family. Full of gratitude and disbelief at the success they’ve had together, both Kix Brooks and Ronnie Dunn thanked those for attending the exhibit grand opening. “For a couple of guys that didn't know each other from Adam, didn't really want to do this, it just didn’t make any sense,” Brooks explained about the decision to team up as a duo when he and Dunn were both in their mid-30s. “We’d both been around the block for a long time. But, we were also pretty broke. When somebody throws any kind of opportunity in front of you in the music business, you generally take it and try to make the best of it. That same week we met, we wrote our first two No. 1 records, and when ‘Brand New Man’ was a No. 1 hit, we knew, 'Now we're in business.'” The exhibit itself includes a brief history of both Brooks and Dunn’s rise to superstardom individually and together. Dunn’s childhood red cowboy boots are on display, while sheet music and early album covers from Brooks are included. -

Media Jukebox Songbook

MEDIA JUKEBOX SONGBOOK 1 (THERE'S GOTTA BE) MORE TO LIFE STACIE ORRICO 2 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT 3 26 CENTS THE WILKINSONS 4 99.9% SURE (NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE) BRIAN McCOMAS 5 A SORTA FAIRYTALE TORI AMOS 6 ABSOLUTELY (STORY OF THE GIRL) NINE DAYS 7 ACCIDENTLY IN LOVE COUNTING CROWS 8 AFRICA TOTO 9 AGAINST ALL ODDS PHIL COLLINS 10 AHAB THE ARAB RAY STEVENS 11 AIN'T IT FUNNY JENNIFER LOPEZ 12 ALL FOR YOU JANET 13 ALL THAT JAZZ CATHERINE ZETA JONES 14 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 15 ALL THE THINGS SHE SAID T.A.T.U. 16 AMAZING JOSH KELLEY 17 AMAZING GRACE ELVIS PRESLEY 18 AMERICAN PIE MADONNA 19 ANGRY AMERICAN (COURTESY OF THE RED WHITE & BLUE) TOBY KEITH 20 ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE BRANDY 21 ANOTHER DUMB BLOND HOKU 22 ANYTHING THIRD EYE BLIND 23 ARE YOU HAPPY NOW? MICHELLE BRANCH 24 ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT? ELVIS PRESLEY 25 AULD LANG SYNE TRADITIONAL 26 BABY BOY BEYONCE KNOWLES f/SEAN PAUL 27 BABY ONE MORE TIME BOWLING FOR SOUP 28 BABYLON DAVID GRAY 29 BACK IN BABY'S ARMS PATSY CLINE 30 BACKSEAT OF A GREYHOUND BUS SARA EVANS 31 BAG LADY ERYKAH BADU 32 BEAUTIFUL CHRISTINA AGUILERA 33 BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10,000 MANIACS 34 BEER FOR MY HORSES TOBY KEITH/WILLIE NELSON 35 BETTER OFF ALONE ALICE DEEJAY 36 BEYOND THE SEA BOBBY DARIN 37 BIG YELLOW TAXI AMY GRANT 38 BIGGER THAN MY BODY JOHN MAYER 39 BLACK MAGIC WOMAN SANTANA 40 BLUE (DA BE DEE) EIFFEL 65 41 BLUE SUEDE SHOES ELVIS PRESLEY 42 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 43 BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE TASTE OF HONEY 44 BOOTYLICIOUS DESTINY'S CHILD 45 BREAKING UP IS HARD TO DO NEIL SEDAKA 46 BREATHE MELISSA ETHERIDGE -

Towards a Historical View of Country Music Gender Roles

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Theses Department of Sociology 12-4-2006 Stand By Your Man, Redneck Woman: Towards a Historical View of Country Music Gender Roles Cenate Pruitt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Pruitt, Cenate, "Stand By Your Man, Redneck Woman: Towards a Historical View of Country Music Gender Roles." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses/12 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STAND BY YOUR MAN, REDNECK WOMAN: TOWARDS A HISTORICAL VIEW OF COUNTRY MUSIC GENDER ROLES by CENATE PRUITT Under the Direction of Wendy S. Simonds ABSTRACT Country music, considered a uniquely American musical genre, has been relatively under-researched compared to rock and rap music. This thesis proposes research into the topic of country music, specifically the ways which country music songs portray gender. The thesis uses Billboard chart data to determine commercially successful songs, and performs a content analysis on the lyrics of these songs. I will select songs from a fifty year period ranging from 1955 to 2005, so as to allow for a longitudinal study of potential changes in -

Garth Songs: Ainʼt Going Down Rodeo the Dance Papa Loves Mama the River Thunder Rolls That Summer Much Too Young Baton Rouge

Garth songs: Ainʼt going down Rodeo The dance Papa loves mama The river Thunder rolls That summer Much too young Baton Rouge Tim McGraw Live like you were dying Meanwhile back at mamas Donʼt take the girl The highway donʼt care Sleep on it Diamond rings and old barstools Red rag top Shot gun rider Green grass grows I like it I love it Something like that Miranda Lambert: Baggage claim Tin man Vice Mamas broken heart Pink sunglasses Gunpowder and lead Kerosene Little red wagon House that built me Famous in a small town Hell on heels Alan Jackson: Chattahootchie Here in the real world 5 oʼclock somewhere Remember when Mercury blues Donʼt rock the jukebox Chasing that neon rainbow Summertime blues Must be love Whoʼs cheating who Vince Gill: Liza Jane Cowgirls do Dont let our love start slipping away I still believe in you Trying to get over you One more last chance Whenever you come around Little Adriana Shania Twain: Still the one Whoʼs bed have your boots been under Any man of mine From this moment on No one needs to know Brooks and Dunn: Neon moon Rock my world My Maria Boot scootin boogie Brand new man Red dirt road Hillbilly delux Long goodbye Believe Getting better all the time George strait All my exes Fireman The chair Check yes or no Amarillo by morning Ocean front property Carrying your love with me Write this down Loves gonna make it Blake Shelton God gave me you Boys round here Home Neon light Some beach Old red Sangria Turning me on Who are you when Iʼm not looking Lonely tonight Toby Keith: Shoulda been a cowboy Red solo cup