Private Security in Practice: Case Studies from Southeast Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employment Application 2013

Mississippi Security Police Inc. 3003 Pascagoula Street Pascagoula, MS 39567 228.762.0661 228.769.5583 fax Dear Applicant: Please comply with the following requirements. Please review qualifications and requirements on back of form before completing application. YOU MUST ATTACH a copy of the following along with your application: • High School Diploma or GED College Degree (if applicable) • Driver’s License TWIC® Card (if applicable) • Social Security Card DD214 (if applicable) Training Certificates (if applicable) Submission of an application does not constitute an offer of employment. All applications will be kept on file for six months. Incomplete applications will not be considered. Remove this top sheet before returning application. Please do not call the office to inquire on the status of your application. You will be contacted should a qualifying position be available. If you are contacted, the application process will consist of the following: • Criminal Background Investigation • Motor Vehicle Report • Drug Test • Physical (if applicable) • Credit Check (if applicable) The application process takes seven to ten business days to complete. Upon successful completion of background requirements you will be contacted for the next phase of the interview process. All inquires will be made through the Human Resources office. TRANSPORTATION WORKER IDENTIFICATION CREDENTIALS (TWIC® ) Beginning September 2008, the federal government began requiring additional identification of workers at Port and Refinery locations throughout the United States. As MSP provides security services for these locations, our employees are required to acquire a TWIC® card prior to employment. The application process for a TWIC® card can be a long process. You are responsible for the application and cost of obtaining a TWIC® card. -

Private Security Companies – Normative Inferences

PRIVATE SECURITY COMPANIES – NORMATIVE INFERENCES Report for the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries as a Means of Violating Human Rights and Impeding the Exercise of the Right of Peoples to Self-Determination December 2015 Ottavio Quirico [email protected] Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Allowed P(M)SC Activities: Security and (Non-)Military Services ....................................... 1 1.1. Permitted Conduct: Security Services (Police Functions) ............................................ 1 1.2. Use of (Armed) Force ........................................................................................................ 5 1.3. Military Activities: Prohibited Conduct? ......................................................................... 6 2. Licensing, Commercialising and Using (Fire-)Arms ............................................................... 9 3. Licensing, Authorising and Registering PSCs and Their Personnel .................................... 11 4. Enforcement: Monitoring and Reparation .............................................................................. 14 5. Applicable Law ............................................................................................................................ 18 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Selected References.......................................................................................................................... -

POLICE AUTHORITY District

Wayne County Community College POLICE AUTHORITY District The safety and security of all students, faculty, staff, and visitors are of great concern to the Wayne County Community College District (WCCCD). In an effort to enhance the District’s campus safety services WCCCD’s three Detroit campuses are gaining a higher level of security staff. WCCCD Security Police Authority, a un-armed law enforcement agency now has complete police authority to apprehend and arrest anyone involved in illegal acts on the campus. In the event of a major offense (i.e., aggravated assault, robbery, and auto theft) the WCCCD Security Police Authority would report the offense to the local police and pursue joint investigative efforts. If minor offenses involving college rules and regulations are committed by a student, the campus Security Police Authority may also refer the individual to the disciplinary division of Student Affairs. With oversight from the Michigan Commission of Law Enforcement Standards (MCOLES), a division of the Michigan State Police, the Police Authority was also approved by the Wayne County Prosecutor and the Detroit Police Chief. WCCCD has officers sworn in as Security Police Officers, also referred to as "Arrest Authority" Security, and have misdemeanor arrest authority while on active duty, on the District’s premises and in full uniform. The Director of Campus Safety is responsible for licensure and all of the officers that have the arrest authority must meet minimum requirements related to age, security or law enforcement experience and suitable background including absence of any felony conviction and specific misdemeanor convictions. The law requires these employees to be trained as required by the Michigan State Police. -

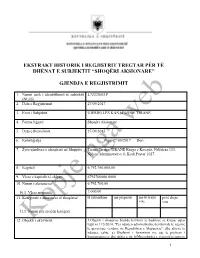

Datë 06.03.2021

EKSTRAKT HISTORIK I REGJISTRIT TREGTAR PËR TË DHËNAT E SUBJEKTIT “SHOQËRI AKSIONARE” GJENDJA E REGJISTRIMIT 1. Numri unik i identifikimit të subjektit L72320033P (NUIS) 2. Data e Regjistrimit 27/09/2017 3. Emri i Subjektit UJËSJELLËS KANALIZIME TIRANË 4. Forma ligjore Shoqëri Aksionare 5. Data e themelimit 27/09/2017 6. Kohëzgjatja Nga: 27/09/2017 Deri: 7. Zyra qëndrore e shoqërisë në Shqipëri Tirane Tirane TIRANE Rruga e Kavajës, Ndërtesa 133, Njësia Administrative 6, Kodi Postar 1027 8. Kapitali 6.792.760.000,00 9. Vlera e kapitalit të shlyer: 6792760000.0000 10. Numri i aksioneve: 6.792.760,00 10.1 Vlera nominale: 1.000,00 11. Kategoritë e aksioneve të shoqërisë të zakonshme me përparësi me të drejte pa të drejte vote vote 11.1 Numri për secilën kategori 12. Objekti i aktivitetit: 1.Objekti i shoqerise brenda territorit te bashkise se krijuar sipas ligjit nr.l 15/2014, "Per ndarjen administrative-territoriale te njesive te qeverisjes vendore ne Republiken e Shqiperise", dhe akteve te ndarjes, eshte: a) Sherbimi i furnizimit me uje te pijshem i konsumatoreve dhe shitja e tij; b)Mirembajtja e sistemit/sistemeve 1 te furnizimit me ujë te pijshem si dhe të impianteve te pastrimit te tyre; c)Prodhimi dhe/ose blerja e ujit per plotesimin e kerkeses se konsumatoreve; c)Shërbimi i grumbullimit, largimit dhe trajtimit te ujerave te ndotura; d)Mirembajtja e sistemeve te ujerave te ndotura, si dhe të impianteve të pastrimit të tyre. 2.Shoqeria duhet të realizojë çdo lloj operacioni financiar apo tregtar që lidhet direkt apo indirect me objektin e saj, brenda kufijve tè parashikuar nga legjislacioni në fuqi. -

126212NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. " ••\ HOW WILL PRIVATIZATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT SERVICES AFFECT SACRAMENTO BY THE YEAR 19991 .' ; ~, J: . ;~ " By ie l Lt. Edward Doonan Sacramento County Sheriff's Department ;. I, •• P.O.S.T. COWvfAND COLLEGE CLASS 9 COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND ~RAINING December 1989 9-0160 • • • • NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE NATIONAL CRThtflNAL JUSTICE REFERENCE SERVICE • (NIJ /NCJRS) Abstract • • 126212 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organiza!lon originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of • Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material In mi- crofiche pllly has peen granted.by _ P Calltornla Commlsslon on . eace ufflcer Standards & Tralnlng to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). • Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. .- ! • HOW WILL PRIVATIZATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT SERVICES AFFECT SACRAMENTO BY THE YEAR 1999? By • Lt. Edward Doonan Sacramento County Sheriff's Department P.O.S.T. COMMAND COLLEGE CLASS 9 COM1vlISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING • December 1989 • • • How Will Privatization of Law Enforcement Services Affect Sacramento By The Year 1999? Eward Doonan. Sponsoring Agency: California Commission on Peace Officer • Standards and Training. 1987. 105 pp. Availability: Commission on POST, Center for Executive Development, 1601 Alhambra Blvd., Sacramento, CA 95816-7053. Single copies free; Order number 9-0160. -

Environmental and Risk Assessment of the Timok River Basin 2008

REC GREY PAPER Environmental and Risk Assessment of the Timok River Basin 2008 ENVSEC Initiative DISCLAIMER The opinion expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the REC, UNECE or any of the ENVSEC partners. 1 AUTHORS: Momir Paunović, PhD, University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Serbia Ventzislav Vassilev, SIECO Consult Ltd. Bulgaria Svetoslav Cheshmedjiev, SIECO Consult Ltd. Bulgaria Vladica Simić, PhD, Institute for Biology and Ecology, University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Science, Serbia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The present report was developed with contributions by: Mr. Stephen Stec, Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe Ms. Cecile Monnier, Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe Ms. Jovanka Ignjatovic, Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe Ms. Ella Behlyarova, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Mr. Bo Libert, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Mr. Milcho Lalov, Major of Bregovo municipality Ms. Danka Marinova, Danube River Basin Directorate - Pleven, Bulgaria 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................................................2 ABBREVIATIONS...............................................................................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................6 -

Criminal Justice Agencies New York

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .4!Q' ... ~~--""'::';.c..;..,.\ ~..l ' . ., ',l LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ~DMINISTRAT'ON ,/ This microfiche was produced from documents received for inclusion in the NCJRS data base. Since NCJRS cannot exercise control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, r - , ~ the individual frame quality will vary. The resolution chart on CRIMINAL JUSTICE this frame may be used to evaluate the document quality. AGENCIES ;; ; IN 1.0 NEW YORK 1971 1.1 111111.8 111111. 25 111111.4. 111111.6 ... ,i MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS-1963-A .Microfilming procedures used to create this fiche comply with the standards set forth in 41CFR 101·11.504 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF LAVf ENFORCEMENT AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE Points of view or opinions stated in this document are STATISTICS DIVISION those of the authorl s] and do not represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. WASHINGTON, D. C. ISSUED FEBRUARY 1972 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE· LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL CRIMINAL· JUSTICE ~EFERENCE SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20531 ....., \ "j7 /20/76 \ LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION Jerris Leonard Administrator TABLE OF CONTENTS , . Richard W. Velde Section Page Clarence M. Coster Associate Administrators FOREWORD. " " " " a " . v NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF LAW ENFORCEMENT NATIONAL SUMMARY. 1 AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE Martin B. Danziger, Acting Assistant Administrator LIMITATIONS OF DATA . " " . " " , " " 3 STATISTICS DIVISION DEFINITIONS OF LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT " " 4 George E. Hall, Director . Statistical Programs DEFINITIONS OF TYPES OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE AGENCIES . 5 Anthony G, Turner, Chief CODE IDENTIFIERS. -

Article UNMANNING the POLICE MANHUNT: VERTICAL SECURITY

Socialist Studies / Études socialistes 9 (2) Winter 2013 Copyright © 2013 The Author(s) Article UNMANNING THE POLICE MANHUNT: VERTICAL SECURITY AS PACIFICATION1 TYLER WALL Assistant Professor, School of Justice Studies Eastern Kentucky University2 Abstract This article provides a critique of military aerial drones being “repurposed” as domestic security technologies. Mapping this process in regards to domestic policing agencies in the United States, the case of police drones speaks directly to the importation of actual military and colonial architectures into the routine spaces of the “homeland”, disclosing insidious entwinements of war and police, metropole and colony, accumulation and securitization. The “boomeranging” of military UAVs is but one contemporary example how war power and police power have long been allied and it is the logic of security and the practice of pacification that animates both. The police drone is but one of the most nascent technologies that extends or reproduces the police’s own design on the pacification of territory. Therefore, we must be careful not to fetishize the domestic police drone by framing this development as emblematic of a radical break from traditional policing mandates – the case of police drones is interesting less because it speaks about the militarization of the police, which it certainly does, but more about the ways in which it accentuates the mutual mandates and joint rationalities of war abroad and policing at home. Finally, the paper considers how the animus of police drones is productive of a particular form of organized suspicion, namely, the manhunt. Here, the “unmanning” of police power extends the police capability to not only see or know its dominion, but to quite literally track, pursue, and ultimately capture human prey. -

Perzierja Dhe Hollimi I Produkteve Te Pastrimit Dhe Te Trajtimit Te Ujit Te Pijshem”

PERMBLEDHJE JOTEKNIKE PËR AKTIVITETIN: “Perzierja dhe hollimi I produkteve te pastrimit dhe te trajtimit te ujit te pijshem” Vendodhja: Rruga “Ura Beshirit”, fshati Lalm, Njesia Administrative Vaqarr, Bashkia Tirane. Kërkues: Subjekti: “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh Janar, 2021 1 TË PERGJITHSHME Subjekti juridik “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh me administrator Z. Leonardo Volpicella, është regjistruar në QKB me NUIS, L21409008V për ushtrimin e veprimtarisë në fusha te ndryshme ku perfshihet edhe: Prodhim, perpunim dhe tregtim te produkteve kimike ne pergjithesi dhe dytesore qe kane perdorim te ndryshem si industriale, ekologjike, farmaceutike, kozmetike dhe shtepiake, detergjent, detersive dhe produkte higjene; produkte per trajtimin e ujerave; produkte per trajtimin dhe riciklimin e mbetjeve urbane dhe/ose industriale dhe toksike; prodhim dhe/ose te materialeve plastike dhe derivate; drejtim, mirembajtje, kontroll, nepermjet menaxhimit te duhur te impianteve te ujerave te pishem me paradisinfektim, aglomerizim, filtrim i shpetje dhe postdezinfektim i ujerave siperfaqesore te lumenjeve, liqeneve dhe te ngjashme nepermjet impianteve te posacme te ngritjes me cfaredolloje fuqie si dhe pastrimin e ujerave shkarkues; ndertim dhe menaxhim i impianteve te pastrimit, dezinfektim i ambienteve, perpunim dhe depozitim per llogari te te treteve te produkteve kimike, kerkim dhe zhvillim i produkteve dhe teknologjive te reja lidhur me objektin e shoqerise. Subjekti “CHEMICA D’AGOSTINO S.P.A.” dshh ushtron aktivitetin e tij në adresën: Rruga “Ura Beshirit”, fshati Lalm, Njesia Administrative Vaqarr, Bashkia Tirane. 2 PËRSHKRIM I PROJEKTIT 2.1 Qëllimi iprojektit Qëllimi i funksionimit te ketij aktiviteti eshte ofrimi i produkteve kimike te nevojshme per tregun vendas. Keto produkte jane te kerkuara nga konsumatori dhe te domosdoshme per mbarefunksionimin e nje sere aktivitetesh dhe ofrimin e disa sherbimeve private ose publike. -

MP Training Team in Republic of Liberia MILITARY POLICE Oaa

MP Training Team In Republic of Liberia MILITARY POLICE Oaa Capt George R. Kaine SP4 Dan Pribilski Editor Associate Editor VOLUME XIII September, 1963 NUMBER 2 Officers FEATURE ARTICLES Assignment: Liberia --- - - - - - - - - - - 5 President Backward Glance at Yongdongpo -------------- 8 Col Robert E. Sullivan Subject: 22d A nniversary -------------------------------------- ----------------- 11 Watch on the Wall ------ --------------------------------- ------14 Honorary President. City of Light . O rganized A gainst Crime ........................... -----------16 Maj Gen Ralph J. Butchers Provost Marshal, Major Command -------------- -------- ---------- 18 TPMGTPTM ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- 19 M ilitary Police Corps .. .. .. -....... ... .. - 19 Vice-President MPs Switch Jobs With Feldjaegers -------------------------------- - 19 Col William C. Curry Fort Myer Dogs Assume New Role ----------------------------- ------------ 20 LD Course U pdated ------------------------------ - ----------- --- --------- ------ 23 Executive Council Vietnam MP School Opens Officer Program ........................--- ---------24 Col Homer E. Shields Sergeant M ajor D eals in Pickelhaube ......................................- 25 Send Us the Man Who Writes ---------------------------------------- 25 Lt Col John F. Kwock Lt Col Harold M. Schwiebert REGULAR FEATURES Maj Leland H. Paul Capt Lloyd E. Gomes Journaletters .------------- 3 Unit Membership Awards 24 Bulletin Board 4 MPA Roundup 26 Capt Matthew -

Lista E Kontratave Te Lidhura Ne Drq Tirane

LISTA E KONTRATAVE TE LIDHURA NE DRQ TIRANE Nr /Dt e Vlera e Gjatesi lidhjes Segmentet rrugore Kontraktori Supervizori Kontrates me a Kontrates TVSH K/Rr. Nr. 54 (Trau Dajt) - Deg. dj. maja e Dajtit, Deg. dj. maja e Dajtit - St. GJOKA teleferikut, Deg. dj. maja e K - 2 30.12.2015 - KONSTRUKSION Dajtit - Vila Qeveritare, Vila 1 30.12.2017 2 81.6 administrator Z. Gjeokonsult shpk 95.992.158 Qeveritare - maja e Dajtit, vjeçare Rrok Gjoka Cel. Tiranë (Fresku) - Surrel, 0692027997 Surrel - Qafë Priskë, Qafë Priskë - deg. dj. Q. Mollë,deg. dj K/Sauk – Senatorium, K/Sauk – Ibë, Ibë – Qafë Krrabë (Km 29), Qafë Krrabë (Km 29) – rot. re VICTORIA INVEST K - 3 31.12.2015 - Shijon, rot. re Shijon – Ura Admin. Zj. Valbona 2 31.12.2017 2 e Zaranikës, K/Km 22 – 74.05 Gjeokonsult shpk 137.681.240 Kuci Cel. vjeçare Qytezë Krrabë, Qytezë 0696552291 Krrabë – Pika Sipër Radio, Degëzim Miniera – Objekti X, Rotondo Sauk – Sauk i Vjetër, Uzi Fushë Krujë (deg. Y) - Fushë Krujë (qendër), Fushë Krujë (qendër) - K/Thumanë Qendër, K/Thumanë K - 5 30.12.2015 - JUBICA admin Z. Qendër - Ura e Drojës (aksi 3 30.12.2017 2 72 Ndoc KULLA , Cel. Gjeokonsult shpk 98.395.910 i vjetër ), Fushë Krujë - vjeçare 0694005877 Halilaj, Halilaj - Krujë, K/Rr. Kombëtare (e vjetra) - Bilaj (Llixha),K/Rr. Kombëtare (e vjetra) - Fabrike e Çimentos K/Shirgjan (K/Rr.Nr.70) - Llixha, Llixha - Kaçivel (k.Gramsh), K/Llixhë - K - 7 18.12.2015 - Mjekëz (Uzinë), Elbasan - ALKO IMPEX Admin 4 18.12.2017 2 Gjinar, k/Drizë (k/rr. -

Economic Role of the Roman Army in the Province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE of EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY in POZNAŃ

Economic role of the Roman army in the province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE OF EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ ACTA HUMANISTICA GNESNENSIA VOL. XVI ECONOMIC ROLE OF THE ROMAN ARMY IN THE PROVINCE OF LOWER MOESIA (MOESIA INFERIOR) Michał Duch This books takes a comprehensive look at the Roman army as a factor which prompted substantial changes and economic transformations in the province of Lower Moesia, discussing its impact on the development of particular branches of the economy. The volume comprises five chapters. Chapter One, entitled “Before Lower Moesia: A Political and Economic Outline” consti- tutes an introduction which presents the economic circumstances in the region prior to Roman conquest. In Chapter Two, entitled “Garrison of the Lower Moesia and the Scale of Militarization”, the author estimates the size of the garrison in the province and analyzes the influence that the military presence had on the demography of Lower Moesia. The following chapter – “Monetization” – is concerned with the financial standing of the Roman soldiery and their contri- bution to the monetization of the province. Chapter Four, “Construction”, addresses construction undertakings on which the army embarked and the outcomes it produced, such as urbanization of the province, sustained security and order (as envisaged by the Romans), expansion of the economic market and exploitation of the province’s natural resources. In the final chapter, entitled “Military Logistics and the Local Market”, the narrative focuses on selected aspects of agriculture, crafts and, to a slightly lesser extent, on trade and services. The book demonstrates how the Roman army, seeking to meet its provisioning needs, participated in and contributed to the functioning of these industries.