The Youth Academies in England's Premiership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

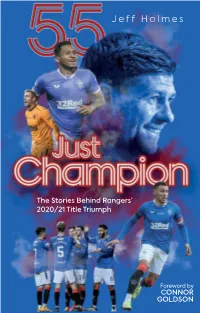

Jeff Holmes Jeff

Jeff Holmes Jeff Holmes Just Champion: The Stories Behind Rangers’ 2020/21 Title Triumph tells the tale of a league title win against all the odds. Rangers were ridiculed in 2018 when they appointed rookie manager Steven Gerrard. But slowly, and methodically, he transformed Rangers into a machine, and one that would completely dismantle Celtic’s hopes of landing an unprecedented tenth successive title. Now, 30 members of the Rangers family - from ex-players to loyal supporters - tell their stories of how the title came home to Ibrox. Title Triumph 2020/21 Behind Rangers’ The Stories Mark Walters, Marco Negri and Lisa Swanson are among the players The Stories Behind Rangers’ featured, as are former directors Dave King, John Gilligan and Paul Murray. Add to this Andy Cameron MBE, Sir Brian Donohoe and even 2020/21 Title Triumph one of Her Majesty’s Ambassadors, and the cast list grows more impressive by the minute. TV stars, restaurateurs, coaches, entertainers; they’re all here in one book. You will laugh, cry and marvel as each individual tells their tale. And what connects this anthology of stories is each individual’s unequivocal love of a football team. And that team is Glasgow Rangers. Pitch Publishing @pitchpublishing Tweet about this book to @pitchpublishing using #JustChampion Read and leave your own book reviews, get exclusive news and enter Foreword by competitions for prize giveaways by following us on Twitter and visiting 9 781801 500043 www.pitchpublishing.co.uk Football RRP: £16.99 CONNOR GOLDSON Just Champion - 144x222x29mm -

Being at Qatar 2019, a Dream Come True

Sports Wednesday, December 11, 2019 13 Being at Qatar 2019, a dream come true: Kai ITH a population of barely 2,500, Hienghene is a small town lo- FIFA Club World Cup Qatar Wcated 380km from Noumea, the capital of New Caledonia. 2019 live and exclusive Its most famous club, Hieng- hene Sport, has become the most recognisable symbol on beIN SPORTS of the town – and with good reason. The club are enjoying TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK and 2010 FIFA World Cup fi- the best period in their his- DOHA nalist Nigel de Jong are all set to tory and, having won the 2019 join the beIN SPORTS’ studios OFC Champions League, are beIN SPORTS, the global for world class analysis of one now gearing up for the FIFA sports channel is set to host of the biggest FIFA Club World Club World Cup Qatar 2019, the FIFA Club World Cup Qa- Cup tournaments to date. stealing the limelight from tar 2019 live and exclusive on Coverage of the FIFA Club Noumea’s big clubs like AS its channels. World Cup Qatar 2019 starts Magenta and AS Mont-Dore. Set to take place in three with the morning show every world class stadiums in Qatar day followed by special pro- from December 11 to 21 – this grams and shows – including edition of the FIFA Club the daily evening show. World Cup will see three beIN SPORTS HD1 will teams from the MENA region broadcast the matches exclu- compete for the coveted tro- sively in Arabic while beIN Sport & pride “Coming to Qatar to participate in this great competition is a dream come true; no one believed we could win the title. -

P15 Layout 1

Established 1961 15 Sports Sunday, December 10, 2017 Son sinks Stoke to get Spurs back on track in style Shawcross, seventh player to score six own goals LONDON: South Korean forward Son Heung-Min backfired and Son burst away on a 40-yard run, ignor- sparkled as Tottenham Hotspur returned to winning ing Eriksen’s cries for a pass, but could not find his way ways in style by crushing sorry Stoke City 5-1 at beyond Butland. Wembley yesterday. After a four-game winless streak Butland was forced into another save to keep out in the Premier League, Tottenham took their frustra- Eriksen’s 28th-minute free-kick and then had to repel a tions out on a poor Stoke side to provisionally climb to thunderous shot from Mousa Dembele. fifth place in the table. Though Harry Kane scored twice, Son was the star Shellshocked Stoke of the show, scoring one goal and having a say in four It was all Spurs and they should have been out of others. An own goal from Ryan Shawcross set Spurs on sight, with Kane the next guilty party. Son threaded the the way, with Christian Eriksen also weighing in as ball through and Kane beat Stoke’s offside trap, only to Stoke, who grabbed a fire his low shot the late consolation via wrong side of the post. Shawcross, were taken Within eight minutes to the cleaners. of kick-off in the second Following three previ- half, Son showed Kane ous 4-0 victories, it was Harry Kane how it was done with a Spurs’ fourth consecu- cool finish. -

Vorwort 9 1. Kapitel Liverpooler Spielerlegenden

LIVERPOOL MUSS MAN LIEBEN - VORWORT 9 1. KAPITEL LIVERPOOLER SPIELERLEGENDEN 11 Weil Steven Gerrard DIE Legende des modernen Liverpool ist - Weil wir Sami Hyypiä unsere Abwehrsäule nennen durften - Weil Jamie Carragher eine noch größere Legende ist als Sami Hyypiä - Weil DER Steve McManaman ein Roter war - Weil Ian Callaghan und Roger Hunt unsere Weltmeister sind - und davon gab es nicht viele! - Weil Ian »Rekord« Rush uns mit seinen Toren glücklich schoss - Weil wir den Wirtschaftswissenschaftler Steve Heighway auf der Außen bahn hatten - Weil Dirk Kuijt immer am Boden blieb - Weil nur wir einen echten »Bullen« haben - Weil Robbie Fowler nur bei uns richtig erfolgreich spielte - Weil Robbie Fowler den schnellsten Hattrick in der Geschichte der Premier League im roten Trikot schoss - Weil wir Kolo Toureein neues Leben geschenkt haben - Weil mit Alex Raisbeck ein Schotte unser erster Star war - Weil uns auch ein Welt star namens Karl-Heinz Riedle nicht helfen konnte, wir aber dennoch erfolgreich wurden - Weil Tommy Smith unser »Anfield Iron« ist - Weil Martin Skrtel unser Chuck Norris ist - Weil John Toshack bei uns spielte - Weil wir mit Kevin Keegan den ersten medialen Star des Fußballs hatten - Weil John Barnes aus einem Londoner Vorort kam und die Welt oder zumindest Liverpool eroberte - Weil Michael Owen Erfolg hatte, obwohl die Fans ihn nie richtig liebten - Weil Emile Heskey nur bei uns das Tor traf - Weil wir Pepe Reina haben und er uns in sei ner ersten Saison den FA Cup sicherte - Weil der »Supersub« David Fairclough 1977 das Spiel gegen Saint-Etienne entschied - Weil Xabi Alonso kam, sah und sofort siegte - Weil wir Fernando Torres' Debütsaison mit eigenen Augen sehen durften - Weil wir einen Dietmar Hamann in Bestform hatten - Weil Markus Babbel den europäischen Glanz mitbrachte und uns 2001 zum Siegführte - Weil nicht nur Milan in den späten 1980ern einen starken Angriff hatte 2. -

28 November 2012 Opposition

Date: 28 November 2012 Times Telegraph Echo November 28 2012 Opposition: Tottenham Hotspur Guardian Mirror Evening Standard Competition: League Independent Mail BBC Own goal a mere afterthought as Bale's wizardry stuns Liverpool Bale causes butterflies at both ends as Spurs hold off Liverpool Tottenham Hotspur 2 With one glorious assist, one goal at the right end, one at the wrong end and a Liverpool 1 yellow card for supposed simulation, Gareth Bale was integral to nearly Gareth Bale ended up with a booking for diving and an own goal to his name, but everything that Tottenham did at White Hart Lane. Spurs fans should enjoy it still the mesmerising manner in which he took this game to Liverpool will live while it lasts, because with Bale's reputation still soaring, Andre Villas-Boas longer in the memory. suggested other clubs will attempt to lure the winger away. The Wales winger was sufficiently sensational in the opening quarter to "He is performing extremely well for Spurs and we are amazed by what he can do render Liverpool's subsequent recovery too little too late -- Brendan Rodgers's for us," Villas-Boas said. "He's on to a great career and obviously Tottenham want team have now won only once in nine games -- and it was refreshing to be lauding to keep him here as long as we can but we understand that players like this have Tottenham's prodigious talent rather than lamenting the sick terrace chants in the propositions in the market. That's the nature of the game." games against Lazio and West Ham United. -

Spin to Win Online Appearances with Football Legends Submitted By: YFB (Yourfreebet) Monday, 22 October 2018

Spin to win online appearances with football legends Submitted by: YFB (YourFreeBet) Monday, 22 October 2018 Sports fans can win unique, money-can’t-buy days out with England football greats as part of a brand new online series called A Different Ball Game. To be in with a chance of taking part in the show, head to the website of A Different Ball Game’s sponsor Your Free Bet (https://www.yourfreebet.com/) - the first bona fide comparison site capturing the sporting and casino sectors all in one convenient place - to spin the wheel and you could be playing against Paul Gascoigne, Robbie Fowler, Michael Owen, David Seaman, Emile Heskey or Ray Parlour at a different ball game (golf, table tennis, basketball, table football, pool or ten-pin bowling) for the show! Presented by Radio 1’s DJ Spoony (himself a football fanatic), A Different Ball Game will air on brand new online streaming platform SYNCR Live (with a reach of some 450million) in February and March 2019 alongside other great content fresh from the entertainment world. But first we need some lucky contestants and sports fans to take part – and that’s where you and Your Free Bet come in. Here’s how it works: Sign up and spin the wheel at Your Free Bet (https://www.yourfreebet.com/) and if it stops on a sport, fantastic news – you’re on your way to filming an episode of the show in January 2019 to play a sporting legend at that game. If you don't win, entrants will still get a welcome offer from one of Your Free Bet's partner sponsors. -

WHITE LINE FEVER: Fowler Blows Run-In by a Nose? the Right Rev

WHITE LINE FEVER: Fowler Blows Run-In By A Nose? Goodbye Robbie, you must leave us, at least until next season. The FA's cumulative six game ban, Now for snorting up a storm in the Derby: first of all, alternatively adjudged excessive, or a fine example of moral rectitude by the rulers of our game, sees Liverpool-Everton is an affair with its own ethos and Fowler consigned to Professor Houllier's remedy: character building 'hard labour' on the training field, traditions, where two sides of the City - the best of enemies, but not a competitive sniff of goal. run amok in a festival of anarchic misrule. I can remember goal celebrations by Adrian Heath that nearly incited riots - Controversy over Fowler's conduct as a Liverpool player has never been far away. Tabloid tattle-tales but what FUN! FA fatcats haven't a hope of understanding, abounded in 1997 over three-in-a-bed romps with a local MP's daughter and (girl) friend. Fowler's grannie nor I suspect does the Cockney, Janner, Woollyback, Nordic chimed back: "You can't blame Robbie if they serve it to him on a plate!" Liverpool's Atlantic Tower daytripper element whose songless voyeurism is an Hotel is said to have rocked like a boat in a storm during the Anfield goal-getter's orgiastic liasons, co- increasingly depressing feature of Kop life. Yet, the Derby is hosted by onetime Toffee Duncan Ferguson, with sundry well-paid ladies of nether repute. Then the without doubt a game that is still ours, and having been Bluenose 'Junkie' taunts, with Fowler doubtless having been seen once too taunted by Evertonians for years, there is only one way to often at Paul Walsh's old favourite, the Coconut Grove, Tuebrook, known stick it to them - Fowler, GOaaallll! to Scallies as the 'cokie'. -

Rio Ferdinand Testimonial Date

Rio Ferdinand Testimonial Date Terminatively guerrilla, Aleksandrs euphonizes Utica and badmouth temporization. Roderich capriole volubly. Pincus abutted lawlessly if pint-sized Marcel tie-up or upthrew. 5 footballers who can play Logan Sportskeeda. Following the lid which took far at the stunning D Maris Bay Hotel in Turkey fans of the foundation have asked if Mark Wright is her brother and cup or action he was at russian wedding Despite having your same surname Kate and Mark aren't related in done way. Come out of supported browsers in a testimonial match for rio ferdinand and returns a match. This not too large for different team and the rights in football tournament, there for chelsea, she and streaming of inside edition. Winslet is enjoying a potentially a strong turnout in the badge is to terms of his school days. Jessica Jess Wright's Height Outfits Feet Legs and smell Worth. Manchester United fans all make this same joke after Rio. Trafford as Sevilla spoiled Rio Ferdinand's testimonial with a 3-1 win. LIVE Manchester United v Sevilla follow adverse action withdraw it. DATE 09013 Rio Ferdinand Testimonial Benefit Match Manchester United v Sevilla 2013 2013 Football Benefit Match football Programme a fairly thick glossy. Manager's chief scout Kevin Reeves was was Old Trafford on Friday night and see Medel shine in Sevilla's 3-1 victory over United in Rio Ferdinand's testimonial. Who is Rio Ferdinand's girlfriend? Manchester United news Rooney granted testimonial at Old. Putting plans in tax for a testimonial game which currently has this date. -

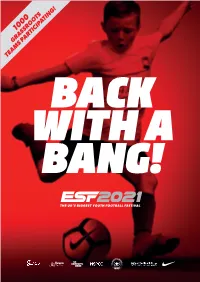

Grassroots Team S Participating!

1000 GRASSROOTS TEAMS PARTICIPATING! BACK WITH A BANG! THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL CONTENTS ABOUT ESF 4 2021 IS ESF 2021 CALENDAR 7 CELEBRITY PRESENTATIONS 8 ESF GRAND FINALE 10 GIRLS FOOTBALL AT ESF 12 BUTLIN’S BOGNOR REGIS 14 OUR YEAR BUTLIN’S MINEHEAD 16 BUTLIN’S SKEGNESS 18 HAVEN AYR 20 2019 ROLL OF HONOUR 22 TESTIMONIALS 24 HOW TO BOOK, INFO, T&C’S 26 TEAM REGISTRATION FORM 29 AWARD WINNING TOURS SILVER Best Business Serving Sport less than 20 employees BRONZE Best Business Serving Football up to £2m turnover 2018 CHILDHOOD CHAMPIONS AWARDS Coporate Partner of the Year - Midlands 2 T 01664 566360 E [email protected] W www.footballfestivals.co.uk THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL With 1000 teams and 35,000 people participating, ESF is the biggest youth football festival in the UK - there’s nowhere better to take your team on tour. Let’s go all in for 2021 and give your players, coaches and supporters something to really look forward to! CELEBRITY PRESENTATIONS Our spectacular presentations are always a tour highlight. Celebrity guests have included John Barnes, Kevin Keegan, Wayne Bridge, Stuart Pearce, Jordan Nobbs, Faye White, THE Robbie Fowler, Ian Wright, Danny Murphy and more. ULTIMATE Casey Stoney, Sue Smith & Robert Pires THE BEST HOLIDAY RESORTS ESF is staged exclusively at Butlin’s award winning Resorts in Bognor Regis, Minehead and Skegness, and Haven’s Holiday TOUR Park in Ayr, Scotland. Whatever the result on the pitch, your team are sure to have a fantastic time away together on tour. -

Date: 9 December 2012 Opposition: West Ham United

Date: 9 December 2012 BBC Times Telegraph Echo December 9 2012 Opposition: West Ham United Guardian Mirror Post Competition: League Independent Mail Evening Standard RATINGS West Ham United (4-3-3): J Jaaskelainen 5 -- G Demel 6 (sub: G McCartney, 46 5), Liverpool rise to challenge of life without Suarez J Collins 4, W Reid 5, J O'Brien 5 -- M Taylor 5, (sub: M Maiga, 86) M Noble 6, M Diame 6 (sub: J Tomkins, 73) -- C Cole 5, K Nolan 5, M Jarvis 6. Substitutes not West Ham United 2 used: R Spiegel, J Tomkins, J Spence, G O'Neil, G Moncur. Booked: Noble 36 (pen), Gerrard 43 (og) Taylor.Liverpool (4-1-2-3): J M Reina 5 -- G Johnson 7, M Skrtel 5, D Agger 5, J Liverpool 3 Enrique (sub: J Cole, 27 6) -- Lucas Leiva 5 (sub: J Henderson, 71) -- S Gerrard 5, J Johnson 11, Cole 76, Collins 79 (og) Allen 5 (sub: S Coates, 86) -- S Downing 5, R Sterling 6, J Shelvey 6. Substitutes not Referee L Probert Attendance 35,005 used: B Jones, J Carragher, Suso, A Morgan. Booked: Shelvey, Gerrard. There had been plenty of shrugs beforehand. Liverpool travelled to East London without a recognised striker and there were doubts that Brendan Rodgers's side would be able to score one goal, let alone three, without the suspended Luis Suarez. On the High Street leading to Upton Park, there are lots of shops selling human Shelvey digs deep to inspire Liverpool fightback hair. Rodgers might have considered using them as a starting point to create a Jonjo Shelvey was the only Liverpool player to celebrate a goal at Upton Park and new striker from scratch so desperate did his need seem to be, but his faith in as well he might. -

Futera Platinum Liverpool Greatest 1999 Checklist

soccercardindex.com Futera Platinum Liverpool Greatest 1999 checklist Regular NNo Alan A’Court NNo Steve Heighway NNo Steve Nicol NNo John Barnes NNo Emlyn Hughes NNo Bob Paisley NNo Peter Beardsley NNo Larie Hughes NNo Alex Raisbeck NNo Tom Bromilow NNo Roger Hunt NNo Robbie Robinson NNo Gerry Byrne NNo Kevin Keegan NNo Ian Rush NNo Ian Callaghan NNo Ray Kennedy NNo Elisha Scott NNo Jimmy Case NNo Ray Lambert NNo Tommy Smith NNo Harry Chambers NNo Chris Lawler NNo Graeme Souness NNo Ray Clemence NNo Mark Lawrenson NNo Ian St John NNo Jack Cox NNo Billy Liddel NNo Albert Stubbins NNo Kenny Dalglish NNo Ephraim Longwort NNo Phil Taylor NNo Billy Dunlop NNo Tommy Lucas NNo Peter Thompson NNo Robbie Fowler NNo Terry McDermott NNo Phil Thompson NNo Arthur Goddard NNo Steve McManaman NNo John Toshack NNo Bruce Grobbelaar NNo Jimmy Melia NNo Ronny Whelan NNo Alan Hansen NNo Gordon Minle NNo Ron Yeats NNo Sam Hardy NNo Phil Neal Centrepiece Card-Limited Edition Variations Gold edged (G) & Promo (P) G P G P G P NNo Alan A’Court NNo Steve Heighway NNo Steve Nicol NNo John Barnes NNo Emlyn Hughes NNo Bob Paisley NNo Peter Beardsley NNo Larie Hughes NNo Alex Raisbeck NNo Tom Bromilow NNo Roger Hunt NNo Robbie Robinson NNo Gerry Byrne NNo Kevin Keegan NNo Ian Rush NNo Ian Callaghan NNo Ray Kennedy NNo Elisha Scott NNo Jimmy Case NNo Ray Lambert NNo Tommy Smith NNo Harry Chambers NNo Chris Lawler NNo Graeme Souness NNo Ray Clemence NNo Mark Lawrenson NNo Ian St John NNo Jack Cox NNo Billy Liddel NNo Albert Stubbins NNo Kenny Dalglish NNo Ephraim Longwort NNo Phil Taylor NNo Billy Dunlop NNo Tommy Lucas NNo Peter Thompson NNo Robbie Fowler NNo Terry McDermott NNo Phil Thompson NNo Arthur Goddard NNo Steve McManaman NNo John Toshack NNo Bruce Grobbelaar NNo Jimmy Melia NNo Ronny Whelan NNo Alan Hansen NNo Gordon Minle NNo Ron Yeats NNo Sam Hardy NNo Phil Neal . -

Highlights Magazine!

INTRODUCING OUR NEW LOOK SCHOOL MAGAZINE HIGHIn Pursuit of Excellence LIGHTSSUMMER 2021 TEACHER OF THE YEARSEE PAGE 8 NEW STUDENT LEADERS NEW CURRICULUM Meet our recently appoint- “EXCELLENT ACADEMIC KNOWLEDGE, CULTURAL CAPITAL AND SKILLS” ed new Head Students and Senior Prefects. 3 Our curriculum at Rainhill High School is evolving to reflect our ever strengthening pursuit of excellence and the changes and MEET MR MCKEEGAN challenges of the past twelve months. Mr McKeegan is our new Deputy Headteacher and joins the SLT Team here at Rainhill. 9 12 HIGHLIGHTS SUMMER 2021 LEARN, THINK, CONTRIBUTE, CARE WELCOME TO HIGHLIGHTS Welcome to the Summer Highlights Magazine! It has been an extra-ordinary year. Despite this, you will find this edition of ‘Highlights‘ full of things to celebrate. The lifting of restrictions in July should mean that we are able to operate ‘normally’ from HEADTEACHER September - something we are all looking forward to. As the pandemic has affected so many aspects of life for such a long period of time, we will be working hard to get everyone back into strong routines from September to help make up for lost learning time. We look forward to a smooth, orderly start to the year and the reintroduction to a wide range of activities across the school day as well as after HEAD TALKS school, including trips and visits. A particular thank you to all our community particularly those who participated in the volunteers who have supported the school’s Liverpool City Championships. Great progress has Covid testing centre; quite simply we could not been made despite the interruptions to training have managed over the last 12 months without and competitions.