Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2D6 Substrates 2D6 Inhibitors 2D6 Inducers

Physician Guidelines: Drugs Metabolized by Cytochrome P450’s 1 2D6 Substrates Acetaminophen Captopril Dextroamphetamine Fluphenazine Methoxyphenamine Paroxetine Tacrine Ajmaline Carteolol Dextromethorphan Fluvoxamine Metoclopramide Perhexiline Tamoxifen Alprenolol Carvedilol Diazinon Galantamine Metoprolol Perphenazine Tamsulosin Amiflamine Cevimeline Dihydrocodeine Guanoxan Mexiletine Phenacetin Thioridazine Amitriptyline Chloropromazine Diltiazem Haloperidol Mianserin Phenformin Timolol Amphetamine Chlorpheniramine Diprafenone Hydrocodone Minaprine Procainamide Tolterodine Amprenavir Chlorpyrifos Dolasetron Ibogaine Mirtazapine Promethazine Tradodone Aprindine Cinnarizine Donepezil Iloperidone Nefazodone Propafenone Tramadol Aripiprazole Citalopram Doxepin Imipramine Nifedipine Propranolol Trimipramine Atomoxetine Clomipramine Encainide Indoramin Nisoldipine Quanoxan Tropisetron Benztropine Clozapine Ethylmorphine Lidocaine Norcodeine Quetiapine Venlafaxine Bisoprolol Codeine Ezlopitant Loratidine Nortriptyline Ranitidine Verapamil Brofaramine Debrisoquine Flecainide Maprotline olanzapine Remoxipride Zotepine Bufuralol Delavirdine Flunarizine Mequitazine Ondansetron Risperidone Zuclopenthixol Bunitrolol Desipramine Fluoxetine Methadone Oxycodone Sertraline Butylamphetamine Dexfenfluramine Fluperlapine Methamphetamine Parathion Sparteine 2D6 Inhibitors Ajmaline Chlorpromazine Diphenhydramine Indinavir Mibefradil Pimozide Terfenadine Amiodarone Cimetidine Doxorubicin Lasoprazole Moclobemide Quinidine Thioridazine Amitriptyline Cisapride -

<I>Iguana Iguana</I>

Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Vol 58, No 6 Copyright 2019 November 2019 by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science Pages 810–816 Use of Rodent Sedation Tests to Evaluate Midazolam and Flumazenil in Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana) Thais F Bressan, Thayanee Sobreira, and Adriano B Carregaro* This study aimed to evaluate the applicability of rodent behavioral tests to assess the effects of midazolam and flumazenil in green iguanas. Four tests commonly used to assess sedation in rodents—the open field test, forced swim test, behavioral scale, and traction test—were conducted in 10 juveniles iguanas. The animals received midazolam (2 mg/kg IM) or 0.9% NaCl (0.4 mL/kg IM), and the tests were conducted between 0 and 300 min thereafter. To verify the effects of midazolam and flumazenil, the most informative tests from the evaluation stage and the limb withdrawal latency time (LWLT) were used. All 10 iguanas were tested under 4 conditions, as follows: MS, midazolam (2 mg/kg IM), followed 30 min later by 0.9% NaCl (0.4 mL/kg IM); FS, flumazenil (0.05 mg/kg IM), followed by 0.9% NaCl (0.4 mL/kg IM) 30 min later; MF, midazolam (2 mg/ kg IM), followed by flumazenil (0.05 mg/kg IM) 30 min later; and CON, 0.9% NaCl (0.4 mL/kg IM). The behavioral scale and the forced swim test showed the best detection of the onset, peak effect, and the differences between the sedated and con- trol iguanas, with testing done between 15 and 240 min after drug administration. -

FDA Approved Drugs with Broad Anti-Coronaviral Activity Inhibit SARS-Cov-2 in Vitro

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.25.008482; this version posted March 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. FDA approved drugs with broad anti-coronaviral activity inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro Stuart Weston1, Rob Haupt1, James Logue1, Krystal Matthews1 and Matthew B. Frieman*1 1 - Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 685 W. Baltimore St., Room 380, Baltimore, MD, 21201, USA *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Key words: SARS-CoV-2, nCoV-2019, COVID-19, drug repurposing, FDA approved drugs, antiviral therapeutics, pandemic, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine AbstraCt SARS-CoV-2 emerged in China at the end of 2019 and has rapidly become a pandemic with over 400,000 recorded COVID-19 cases and greater than 19,000 recorded deaths by March 24th, 2020 (www.WHO.org) (1). There are no FDA approved antivirals or vaccines for any coronavirus, including SARS-CoV-2 (2). Current treatments for COVID-19 are limited to supportive therapies and off-label use of FDA approved drugs (3). Rapid development and human testing of potential antivirals is greatly needed. A potentially quicker way to test compounds with antiviral activity is through drug re-purposing (2, 4). Numerous drugs are already approved for use in humans and subsequently there is a good understanding of their safety profiles and potential side effects, making them easier to test in COVID-19 patients. -

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

Redalyc.Tissue Depletion of Azaperone and Its Metabolite

Revista de Toxicología ISSN: 0212-7113 [email protected] Asociación Española de Toxicología España Mestorino, N.; Marchetti, M. L.; Daniele, M.; Martínez, M. A.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M. R.; Anadón, A. Tissue depletion of azaperone and its metabolite azaperol after oral administration of azaperone in food-producing pigs Revista de Toxicología, vol. 30, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2013, pp. 209-214 Asociación Española de Toxicología Pamplona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=91931189013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Rev. Toxicol. (2013) 30: 209-214 Tissue depletion of azaperone and its metabolite azaperol after oral administration of azaperone in food-producing pigs Mestorino N1* , Marchetti M L1 , Daniele M1 , Martínez M A2 , Martínez-Larrañaga M R2 , Anadón A2 . 1Laboratorio de Estudios Farmacológicos y Toxicológicos (LEFyT), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 1900- La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2Departamento de Toxicología y Farmacología, Facultad de Veterinaria, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040-Madrid, España. Recibido 5 de noviembre de 2013 / Aceptado 20 de diciembre de 2013 Abstract: Azaperone is a butyrophenone tranquilizer for swine. establecidos por la Unión Europea (100 mg / kg en el músculo, el Food producing pigs are particularly sensitive to stress during hígado, los riñones y la piel + grasa) en ningún momento del handling and transport to the abattoir. In vivo, azaperone is partially muestreo. Como consecuencia, según los resultados obtenidos en el metabolised to azaperol, a metabolite with pharmacological activity. -

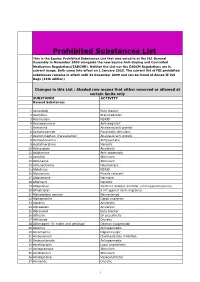

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Parkinson’s Disease Volume 2015, Article ID 609428, 71 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/609428 Review Article Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson’s Disease Philippe Huot,1,2,3 Susan H. Fox,1,2 and Jonathan M. Brotchie1 1 Toronto Western Research Institute, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, 399 Bathurst Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M5T 2S8 2Division of Neurology, Movement Disorder Clinic, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 399BathurstStreet,Toronto,ON,CanadaM5T2S8 3Department of Pharmacology and Division of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, UniversitedeMontr´ eal´ and Centre Hospitalier de l’UniversitedeMontr´ eal,´ Montreal,´ QC, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Jonathan M. Brotchie; [email protected] Received 19 September 2014; Accepted 26 December 2014 Academic Editor: Maral M. Mouradian Copyright © 2015 Philippe Huot et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are secondary to a dopamine deficiency in the striatum. However, the degenerative process in PD is not limited to the dopaminergic system and also affects serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons. Because they can increase monoamine levels throughout the brain, monoamine reuptake inhibitors (MAUIs) represent potential therapeutic agents in PD. However, they are seldom used in clinical practice other than as antidepressants and wake-promoting agents. This review article summarises all of the available literature on use of 50 MAUIs in PD. The compounds are divided according to their relative potency for each of the monoamine transporters. -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Anesthesia and Analgesia in Laboratory Animals

GUIDELINES ON ANESTHESIA AND ANALGESIA IN LABORATORY ANIMALS University of South Florida provides the following guidelines for use by IACUC-certified faculty and staff. CONTENTS PAGE A. Background……………………………………………………….…………………………… 1 B. Definitions....……………………………………………………..…………………………….. 2 C. General Considerations……………………………………….,…………………………….. 3 D. Controlled Substances……………………………………….……………………………… 3 E. Pre-Anesthetic Treatments………………………………….………………………………. 4 F. General Anesthetics………………………………………….………………………………. 4 G. Neuromuscular Blocking Agents………………………….……………………………….. 5 H. Monitoring Anesthesia…………………………………….…………………………………. 6 I. Analgesics……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 J. Comments regarding Anesthetics and Analgesics……………………………………... 7 REFERENCE TABLES PAGE I. Signs of Pain and Distress in Laboratory Animals………………………………………… 10 II. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Mice….………..…...….………...…… 11 III. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Rats……………………………...…… 12 IV. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Gerbils……….……………..…….. 13 V. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Hamsters…….……………..……. 14 VI. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Guinea Pigs….…………….….……. 15 VII. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Rabbits.……...…………….………… 16 VIII. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Dogs.…………………….…………… 17 IX. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Cats.……………………..…………… 18 X. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics for Pigs ..……………..….………………..19 XI. Commonly Used Anesthetics and Analgesics -

Antipsychotics

The Fut ure of Antipsychotic Therapy (page 7 in syllabus) Stepp,,hen M. Stahl, MD, PhD Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychiatry Universityyg of California, San Diego School of Medicine Honorary Visiting Senior Fellow, Cambridge University, UK Sppyonsored by the Neuroscience Education Institute Additionally sponsored by the American Society for the Advancement of Pharmacotherapy This activity is supported by an educational grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Copyright © 2011 Neuroscience Education Institute. All rights reserved. Individual Disclosure Statement Faculty Editor / Presenter Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, is an adjunct professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and an honorary visiting senior fellow at the University of Cambridge in the UK. Grant/Research: AstraZeneca, BioMarin, Dainippon Sumitomo, Dey, Forest, Genomind, Lilly, Merck, Pamlab, Pfizer, PGxHealth/Trovis, Schering-Plough, Sepracor/Sunovion, Servier, Shire, Torrent Consultant/Advisor: Advent, Alkermes, Arena, AstraZeneca, AVANIR, BioMarin, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx, Cypress, Dainippon Sumitomo, Dey, Forest, Genomind, Janssen, Jazz, Labopharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Neuronetics, Novartis, Ono, Orexigen, Otsuka, Pamlab, Pfizer, PGxHealth/Trovis, Rexahn, Roche, Royalty, Schering-Plough, Servier, Shire, Solvay/Abbott, Sunovion/Sepracor, Valeant, VIVUS, Speakers Bureau: Dainippon Sumitomo, Forest, Lilly, Merck, Pamlab, Pfizer, Sepracor/Sunovion, Servier, Wyeth Copyright © 2011 Neuroscience Education Institute. All rights reserved. Learninggj Objectives • Differentiate antipsychotic drugs from each other on the basis of their pharmacological mechanisms and their associated therapeutic and side effects • Integrate novel treatment approaches into clinical practice according to best practices guidelines • Identify novel therapeutic options currently being researched for the treatment of schizophrenia Copyright © 2011 Neuroscience Education Institute. -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Emea/666243/2009

European Medicines Agency London, 29 October 2009 EMEA/666243/2009 ISSUE NUMBER: 0910 MONTHLY REPORT PHARMACOVIGILANCE WORKING PARTY (PHVWP) OCTOBER 2009 PLENARY MEETING The CHMP Pharmacovigilance Working Party (PhVWP) held its October 2009 plenary meeting on 19-21 October 2009. PhVWP DISCUSSIONS ON SAFETY CONCERNS Below is a summary of the discussions regarding non-centrally authorised medicinal products in accordance with the PhVWP publication policy (see under http://www.emea.europa.eu/htms/human/phv/reports.htm). Positions agreed by the PhVWP for non- centrally authorised products are recommendations to Member States. For safety updates concerning centrally authorised products and products subject to ongoing CHMP procedures, readers are referred to the CHMP Monthly Report (see under http://www.emea.europa.eu/pressoffice/presshome.htm). The PhVWP provides advice on these products to the Committee of Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) upon its request. Antipsychotics - risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) Identify risk factors for VTE for preventive action before and during treatment with antipsychotics The PhVWP completed their review on the risk of VTE of antipsychotics1. The review was triggered by and based on data from the UK spontaneous adverse drug reactions reporting system and the published literature. The PhVWP carefully considered the data, including the limitations of both information sources, such as the lack of randomised controlled trial data, the heterogeneity of published studies and the potential confounding factors such as sedation and weight gain, commonly present in antipsychotic users. The PhVWP concluded that an association between VTE and antipsychotics cannot be excluded. Distinguishing different risk levels between the various active substances was not possible.