II Profile of Bands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aoife Miskelly Soprano

Aoife Miskelly Soprano Northern Irish soprano Aoife Miskelly Codetta in their performance – live on studied as a Sickle Foundation Scholar on the Spanish radio – of Beethoven’s oratorio Christ Opera Masters degree course at the Royal on the Mount of Olives in Cuenca. Aoife is also Academy of Music in London, graduating in a very keen oratorio singer, having performed 2012 with the Regency Award. During her in a whole host of concerts, including Bach’s studies, Aoife was a Kathleen Ferrier Awards Christmas Oratorio, St. John and Matthew finalist (2010), won a BBC Northern Ireland Passions, Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen and Young Artists Platform Award, and was a Magnificat, Beethoven’s Mass in C (in Samling Scholar, Internationale Cologne Cathedral), Brahms’ Deutches Meistersinger Akademie Young Artist and Requiem (St. Martin in the Fields), Carissimi’s Britten-Pears Young Artist. Aoife was the Jepthe (St. John’s, Smith Square), Handel’s winner of the Hampshire National Singing Messiah, Dixit Dominus, Laudate Pueri Competition in 2011, the Bernadette Greevy Dominum, and Saul (conducted by Laurence Bursary in 2011, finalist in the Veronica Dunne Cummings), Mozart’s Requiem, Coronation International Singing Competition 2013, and Mass and Exultate Jubilate, Orff’s Carmina finalist in the 2015 Wigmore Hall Song Burana (Ulster Orchestra), Poulenc’s Gloria, Competition. Stravinsky’s Mass, Varese’s Nocturnal and Vivaldi’s Gloria. During the 2012-16 seasons Aoife was a soloist at the Cologne Opera House where she Aoife’s recent highlights include -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

2013-14 Page 2 Page

Arts Council of Northern Ireland - 2013-14 www.artscouncil-ni.org arts council of northern ireland annual review 2013-14 arts council of northern ireland annual review 2013-14 Prime Cut Production’s ‘The Conquest of Happiness’ Happiness’ of ‘The Conquest Production’s Cut Prime page 2 page page 3 page Our Vision Front Cover: Lyric Theatre Production, ‘Brendan at the Chelsea’. Photo: Steffan Hill Steffan Photo: Chelsea’. the at ‘Brendan Production, Theatre Lyric Cover: Front Our vision is to ‘place the arts at the heart of our social, economic and creative life’. In Ambitions for the Arts*, our new five-year strategic plan for the development of the arts in Northern Ireland, 2013-18, we identify the main themes covering what we believe needs to be done to achieve this vision - championing the arts, promoting Public funding brings access, building a sustainable sector. In this Annual Review 2013-14, you will see the great art within the reach progress that has been made in these areas, from the transformation of Derry~Londonderry through the UK City of Culture 2013 creative programme to the range of everyone of international showcase opportunities now available to our artists and performers. * available at www.artscouncil-ni.org arts council of northern ireland annual review 2013-14 arts council of northern ireland annual review 2013-14 Contents Welcome Welcome to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s Annual Review 2013-2014. Chair’s Foreword 6 This calendar-style review of our combined Exchequer and Chief Executive’s Foreword 8 National Lottery-funded activities covers many of the artistic highlights of the last (financial) year, expanding in greater detail on several of the most significant events. -

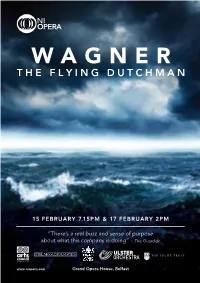

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

EXEMPTIONS the Following Issues Have Been Removed Under Freedom of Information: FOI Exemption Section 23 Commercial Interests It

EXEMPTIONS The following issues have been removed under Freedom of Information: FOI Exemption Section 23 Commercial Interests Item 4.1, pg 2/3; Ulster Orchestra Report FoI Exemption Section 16 Prejudice to the effective conduct of public affairs Item 8.2, pg 5/6; Media Protocol Item 9.2, pg 6; Delegated Decisions Meeting No 14 2011/12 Minutes of the meeting of the Board of the Arts Council held at MacNeice House on Wednesday 28 March 2012 at 5.00pm 1 ATTENDANCE PRESENT Bob Collins (Chair), Damien Coyle (Vice Chair), David Alderdice, Anna Carragher, Noelle McAlinden, Katherine McCloskey, Ian Montgomery, Paul Seawright, Janine Walker. IN ATTENDANCE Roisin McDonough (Chief Executive) Nick Livingston (Director of Strategic Development) Lorraine McDowell (Director of Operations) Noirin McKinney (Director of Arts Development) Geoffrey Troughton (Director of Finance& Corporate Services) Patricia Curran (DSO to the Directors & Corporate Services) APOLOGIES David Irvine, Paul Mullan, Brian Sore. 2 PREVIOUS MEETING 2.1 Minute – 29 February 2012 The minute of the previous meeting was approved and signed by the Chair. Minute – 30 January 2012 – Special Board meeting The minute was approved and signed by the Vice-Chair. 2.2 Matters Arising There were no matters arising. 3 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST The Chair declared his interest in the Ulster Orchestra and advised that Damien Coyle, Vice- Chair would chair the discussion of item no 4.1. 1 BC/PC Mar 12 * - documents circulated with agenda Meeting No 14 2011/12 4 POLICY ISSUES 4.1 Ulster Orchestra Report* 2 BC/PC Mar 12 * - documents circulated with agenda Meeting No 14 2011/12 Mar 12 * - documents circulated with agenda Meeting No 14 2011/12 5 FINANCIAL UPDATE 5.1 Financial Report* Geoffrey Troughton, Director of Finance & Corporate Services, reported on the management accounts circulated prior to the meeting. -

The Magic Flute Programme

Programme Notes September 4th, Market Place Theatre, Armagh September 6th, Strule Arts Centre, Omagh September 10th & 11th, Lyric Theatre, Belfast September 13th, Millennium Forum, Derry-Londonderry 1 Welcome to this evening’s performance Brendan Collins, Richard Shaffrey, Sinéad of The Magic Flute in association with O’Kelly, Sarah Richmond, Laura Murphy Nevill Holt Opera - our first ever Mozart and Lynsey Curtin - as well as an all-Irish production, and one of the most popular chorus. The showcasing and development operas ever written. of local talent is of paramount importance Open to the world since 1830 to us, and we are enormously grateful for The Magic Flute is the first production of the support of the Arts Council of Northern Austins Department Store, our 2014-15 season to be performed Ireland which allows us to continue this The Diamond, in Northern Ireland. As with previous important work. The well-publicised Derry / Londonderry, seasons we have tried to put together financial pressures on arts organisations in Northern Ireland an interesting mix of operas ranging Northern Ireland show no sign of abating BT48 6HR from the 18th century to the 21st, and however, and the importance of individual combining the very well known with the philanthropic support and corporate Tel: +44 (0)28 7126 1817 less frequently performed. Later this year sponsorship has never been greater. I our co-production (with Opera Theatre would encourage everyone who enjoys www.austinsstore.com Company) of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore seeing regular opera in Northern Ireland will tour the Republic of Ireland, following staged with flair and using the best local its successful tour of Northern Ireland operatic talent to consider supporting us last year. -

Rediscover Northern Ireland Report Philip Hammond Creative Director

REDISCOVER NORTHERN IRELAND REPORT PHILIP HAMMOND CREATIVE DIRECTOR CHAPTER I Introduction and Quotations 3 – 9 CHAPTER II Backgrounds and Contexts 10 – 36 The appointment of the Creative Director Programme and timetable of Rediscover Northern Ireland Rationale for the content and timescale The budget The role of the Creative Director in Washington DC The Washington Experience from the Creative Director’s viewpoint. The challenges in Washington The Northern Ireland Bureau Publicity in Washington for Rediscover Northern Ireland Rediscover Northern Ireland Website Audiences at Rediscover Northern Ireland Events Conclusion – Strengths/Weaknesses/Potential Legacies CHAPTER III Artist Statistics 37 – 41 CHAPTER IV Event Statistics 42 – 45 CHAPTER V Chronological Collection of Reports 2005 – 07 46 – 140 November 05 December 05 February 06 March 07 July 06 September 06 January 07 CHAPTER VI Podcasts 141 – 166 16th March 2007 31st March 2007 14th April 2007 1st May 2007 7th May 2007 26th May 2007 7th June 2007 16th June 2007 28th June 2007 1 CHAPTER VII RNI Event Analyses 167 - 425 Community Mural Anacostia 170 Community Poetry and Photography Anacostia 177 Arts Critics Exchange Programme 194 Brian Irvine Ensemble 221 Brian Irvine Residency in SAIL 233 Cahoots NI Residency at Edge Fest 243 Healthcare Project 252 Camerata Ireland 258 Comic Book Artist Residency in SAIL 264 Comtemporary Popular Music Series 269 Craft Exhibition 273 Drama Residency at Catholic University 278 Drama Production: Scenes from the Big Picture 282 Film at American Film -

BEETHOVEN Missa Solemnis

BEETHOVEN Missa Solemnis Steven Roberts - Conductor Emma Morwood - Soprano Emma Stannard - Mezzo Soprano Christopher Turner - Tenor Andrew Greenan - Bass Manchester Philharmonia Leader – Morven Bryce Altrincham Choral Society Musical Director – Steven Roberts Congleton Choral Society Musical Director – Christopher Cromar Saturday, 17 th November 2018 at 7.30 p.m. Royal Northern College of Music, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9RD Altrincham Choral Society prides itself in offering a diverse, innovative and challenging programme of concerts, including many choral favourites. We are a forward-thinking and progressive choir with a strong commitment to choral training and high standards, so providing members with the knowledge, skills and confidence to thoroughly enjoy their music-making. Rehearsals are on Monday evenings at Altrincham Methodist Church, Barrington Road, Altrincham. Car Park entrance off Barrington Road. Satnavs please use WA14 1HF. We are only a 5 minute walk from the train/metro/bus station. Rehearsals are from 7.45 to 10.00 pm For more information contact us E-mail: [email protected] Tweet us @acs1945 Like us on Facebook ACS has a new website – www.altrinchamchoral.co.uk EXCEPTIONAL SERVICE AWARD The Award for Exceptional Service may be conferred on any member who is deemed to have given exceptional service to the Society. The award may be made to a member who has served for 25 or more years on the Committee or a Sub-Committee. In recognition of their services to the society THE EXCEPTIONAL SERVICE AWARD has been awarded to Pat Arnold John Greenan Colin Skelton Joyce Venables Andrew Wragg Steven Roberts - Conductor Steven is the Conductor and Musical Director of Altrincham Choral Society, Chesterfield Philharmonic Choir and Honley Male Voice Choir. -

Clár Samhraidh Na Nealaíon Agus Cultúir Arts and Culture Summer Programme

Comhairle Ceantair an Iúir, Mhúrn agus an Dúin Newry, Mourne and Down District Council Clár Samhraidh na nEalaíon agus Cultúir Arts and Culture Summer Programme INSIDE: AWARD WINNING BELFAST SINGER SONGWRITER KAZ HAWKINS MARY DORAN AND DAVID JOHNSTON ROCK SCHOOL Ag freastal ar an Dún agus Ard Mhacha Theas Serving Down and South Armagh Welcome DOWN ARTS SEASON PROGRAMME May–August 2019 Seo chugaibh eagrán an tsamhraidh Welcome to the Summer edition of the de chlár Ealaíne, Cultúir agus Arts, Culture and Museum programme Iarsmalainne i gComhairle Ceantair for Newry, Mourne and Down District an Iúir, Mhúrn agus an Dúin. Council. This brochure contains live Tá beo-léirithe, ranganna, ceardlanna, performances, classes, workshops, talks, taispeántais agus imeachtaí speisialta exhibitions and special events across fud fad an cheantair idir Bealtaine the district from May – August, including agus Lúnasa, Séasúr Samhraidh an the Newcastle Summer Season. Chaisleáin Nua san áireamh. It is packed full of entertainment Tá súil agam go mbainfidh sibh sult events for the entire family over the An Comhairleoir as an chlár seo, atá lán d’imeachtaí summer months. It highlights the Council’s Mark Murnin siamsúla don teaghlach ar fad i rith commitment to ensuring that we offer Cathaoirleach na míonna samhraidh. Taispeánann all who live, work and visit the district an clár seo tiomantas na Comhairle as many opportunities as possible to Councillor le cinntiú go bhfuilimid a tabhairt engage with arts and culture. Mark Murnin deiseanna go chách atá ina gcónaí, Chairman ag obair nó ar chuairt sa cheantar dul in ngleic le cúrsaí ealaíne agus cultúir. -

Download Booklet

MAG IC L A N T Sophie Daneman ~ soprano Beth Higham-Edwards ~ vibraphone E D Alisdair Hogarth ~ piano Anna Huntley ~ mezzo-soprano R A George Jackson ~ conductor Sholto Kynoch ~ piano O N Anna Menzies ~ cello Edward Nieland ~ treble H Sinéad O’Kelly ~ mezzo-soprano Natalie Raybould ~ soprano - T S E Collin Shay ~ countertenor Philip Smith ~ baritone Nicky Spence ~ tenor A Mark Stone ~ baritone Verity Wingate ~ soprano C L N A E R S F L Y R E H C Y B S G N O S FOREWORD Although the thought of singing and acting in front of an audience terrifies me, there is nothing I enjoy more than being alone at my piano and desk, the notes on an empty page yet to be fixed. Fortunately I am rarely overheard as I endlessly repeat words and phrases, trying to find the music in them: the exact pitches and rhythms needed to portray a particular emotion often take me an exasperatingly long time to find. One of the things that I love most about writing songs is that I feel I truly get to know and understand the poetry I am setting. The music, as I write it, allows me to feel as if I am inhabiting the character in the poem, and I often only discover what the poem really says to me when I reach the final bar. This disc features a number of texts either written especially for me (Kei Miller, Tamsin Collison, Andrew Motion, Stuart Murray), or already in existence (Kate Wakeling, Ian McMillan, 4th century Aristotle). -

Date/Time User ID Event Title Event Promotor Event Venue Client Event

Date/Time User ID Event Title Event Promotor Event Venue Client Event Ticket Value Ticket Numbers Comp/Conc Event Declined Hospitality Value ACNI Hospitality 09/05/2018 ACNI-GCampbell Hubert And The Yes Sock! Tinderbox Theatre Company Mac Yes £20.00 2 Yes No £0.00 N/A 08/06/2018 ACNI-GCampbell Ignition Tinderbox Mac Yes £10.00 1 Yes No £0.00 N/A 26/07/2018 ACNI-GCampbell Paperboy Youth Music Theatre Lyric Theatre Yes £30.00 2 Yes No £0.00 N/A 04/04/2018 acni-nlivingston Jane Eyre Northern Ballet Grand Opera House Yes £37.00 2 Yes No £0.00 No 11/04/2018 acni-nlivingston The Colleen Bawn Lyric Theatre/Bruiser Theatre Lyric Theatre Yes £26.00 2 Yes No £0.00 No 17/04/2018 acni-nlivingston Abigail's Party The Mac The Mac Yes £36.00 2 Yes No £0.00 No 04/05/2018 goconnor Festival Of Fools Festival Of Fools Writers Square Yes £0.00 0 N/A No £0.00 N/A 09/04/2018 Roisin McDonough (acni-shanna) A Further Shore - Journey To Good Friday Government Of Ireland/Poetry Ireland Lyric No £0.00 1 Yes No £0.00 No 11/04/2018 Roisin McDonough (acni-shanna) The Colleen Bawn Lyric Theatre Lyric Theatre Yes £30.00 2 Yes No £0.00 No 24/04/2018 Roisin McDonough (acni-shanna) Chief Executives' Forum - Dinner Chief Executives' Forum Riddell Hall No £0.00 1 Yes No £30.00 No 16/04/2018 acni-nlivingston Conference Dinner ACNI Sonoma Restuarant, Hilton No £0.00 0 N/A No £25.00 No 05/05/2018 goconnor Festival Of Fools Festival Of Fools Belfast City Centre Yes £0.00 0 N/A No £0.00 N/A 16/04/2018 Roisin McDonough (acni-shanna) Creative Cultural Skills Awards Ceremony Creative -

Orla Mullan Beltane CV

Orla Mullan Playing Age: 30-40 Height: 5’ 5” Eyes: Blue Hair: Dark Brown/Mid Length Voice: Engaging/Strong Training: First in Performing Arts - Acting Route from The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts (LIPA) FILM/TELEVISION 2020, Television, DS Roz McFarlene*, MARCELLA, Buccaneer Media/ITV, Ashley Pearce/Gilles Bannier 2019, Feature Film, Lorraine, A BUMP ALONG THE WAY, Gallagher Films, Shelly Long 2018, Television, Detective, LINE OF DUTY, World Productions/BBC, John Strickland 2016, Television, Maxine, PAULA, BBC, Alex Holmes 2016, Feature Film, Detective Lavery, BAD DAY FOR THE CUT, Six Mile Hill, Chris Baugh 2014, Television, Aoibheann Jackson (Control)*, THE FALL 2, World Productions/BBC, Allan Cubitt 2005, Feature Film, Fashion Student, THE KINKY BOOTS FACTORY, Julian Jarrold 2011, Short Film, Sam Ridley, MARIONETTE, DMC Film, Richard Stephenson 2011, Short Film, Claire, THE PITCH, Northern Film School, Ikechukwu Obi 2010, Television, Andrea Lane, EMMERDALE, ITV Yorkshire, Tim Dowd 2008, Television, Mary, BRITAIN'S GOT THE POP FACTOR, McIntyre Productions/ITV, Peter Kay *recurring THEATRE 2021, Stage, Mum, ON THE STREET WHERE WE LIVE - DANI DIVES IN, The Mac, Rhiann Jeffrey 2020, Stage, Emily Beattie, OUR JIMMY PAST AND PRESENT, David Hull Promotions, William Caulfield 2019, 2018, Musical, Molly (Lead Singer), TITANICDANCE, Millennium Form Productions, Waterfront Belfast/China Tours, Orla Griffin 2019, 2018, Musical, Donna (Lead), CHEZZIE’S CHANCE (Jazz musical), Blue Eagle/Millennium Forum Productions, Dave Duggan 2019, 2018,