Evaluation of ROLS III Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland 2009

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland Project Report No L-13 March 2009 Somalia Water and Land Information Management Ngecha Road, Lake View. P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel +254 020 4000300 - Fax +254 020 4000333, Email: [email protected] Website: http//www.faoswalim.org. Funded by the European Union and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document should be cited as follows: Venema, J.H., Alim, M., Vargas, R.R., Oduori, S and Ismail, A. 2009. Land use planning guidelines for Somaliland. Technical Project Report L-13. FAO-SWALIM, Nairobi, Kenya. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ............................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................vi ABOUT THE GUIDELINES................................................................................ vii 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 1.1 What is land use planning?................................................................. 1 1.2 Recent -

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021 Due to climate change and its associated impacts Somalia is now recording more wet and dry weather events, often with disastrous consequences for the people facing such extremes. It has become even more difficult to predict such sequential events. Currently, more than 80 percent of the country is facing drought conditions in the mid of the primary Gu rainy season. Yet, flash floods have been reported in the last two days following heavy and sporadic rains in Somaliland. In addition, limited climate change adaptive capacities has led to irresponsible socio- economic practices like cutting of river banks to extract irrigation waters, further exposing the communities to climate hazards. For instance, riverine flooding due to open river banks near Baarey and Moyko villages has been reported in Jowhar within Middle Shabelle region. With current climate models predicting extreme temperatures and rainfall in the future within the region, the country is likely to continue experiencing frequent flood and drought events with likely consequences of affecting untold numbers of people, taxing economies, disrupting food production, creating unrest and prompting migrations. FLOODS AND RAINS UPDATE The Gu rains continued to spread across most parts of the country with Somaliland and Puntland experiencing moderate to heavy rains over the last week. Other areas in central and southern regions recorded light to moderate rains. The Ethiopian highlands received moderate rains within the last week. Since 25 May 2021, most parts of Somaliland have been receiving moderate to heavy rains. Localized flash floods caused by the heavy rainfall were reported on 01 May 2021 in parts of Hargeisa district. -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017. -

Puntland and Somaliland: the Land Legal Framework

Shelter Branch Land and Tenure Section Florian Bruyas Somaliland Puntland State of Somalia The Land Legal Framework Situation Analysis United Nations Human Settlement Programme November 2006 Map of Somalia 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Scope and methodology of the study Chapter 1: Introduction Somalia, Somaliland and Puntland 1.1 Background 1.2 Recent history of Somalia 1.3 Clans 1.4 Somaliland 1.5 Puntland 1.6 Land through History 1.6.1 Under colonial rules 1.6.2 After independence Chapter 2: Identification of needs and problems related to land 2.1 Land conflict 2.2 IDPs and refugees 2.2.1 Land tenure option for IDPs 2.3 Limited capacity 2.3.1 Human resources 2.3.2 Capital city syndrome Chapter 3: The current framework for land administration 3.1 Existing land administration 3.1.1 In Somaliland 3.1.2 In Puntland 3.2 Existing judicial system 3.2.1 In Somaliland 3.2.2 In Puntland 3.3 Land and Tenure 3.2.1 Access to land in both regions 3 Chapter 4: A new legal framework for land administration 4.1 In Somaliland 4.1.1 Laws 4.1.2 Organizations 4.2 In Puntland 4.2.1 Law 4.2.2 Organizations 4.3 Land conflict resolution Chapter 5: Analysis of the registration system in both regions 5.2 Degree of security 5.3 Degree of sophistication 5.4 Cost of registering transactions 5.5 Time required for registering transactions 5.6 Access to the system Chapter 6: Minimum requirements for implementing land administration in other parts of the country Chapter 7: Gender perspective Chapter 8: Land and HIV/AIDS References Annexes --------------------------------------- 4 Acknowledgement I appreciate the assistance of Sandrine Iochem and Tom Osanjo who edited the final draft. -

DROUGHT, DISPLACEMENT and LIVELIHOODS in SOMALIA/SOMALILAND Time for Gender-Sensitive and Protection-Focused Approaches

DROUGHT, DISPLACEMENT AND LIVELIHOODS IN SOMALIA/SOMALILAND Time for gender-sensitive and protection-focused approaches JOINT AGENCY BRIEFING NOTE – JUNE 2018 ‘The drought destroyed our house, and by that I mean we lost all we had.’ Farhia,1 Daynile district, Banadir region Thousands of Somali families were displaced to urban centres by the 2017 drought. Research by a consortium of non-government organizations indicates that they do not intend to return home anytime soon. It also shows how precarious and limited are the livelihood opportunities for displaced people in Somalia; how far people’s options are affected by gender; and how changing gender dynamics present further protection threats to both men and women. Comparing the findings for Somaliland with those for the rest of the country, the research underscores the importance of local dynamics for people’s opportunities and protection. Gaps were highlighted in the provision of basic services for women particularly. Local, state and federal authorities, donors, and humanitarian and development actors need to improve displaced people’s immediate access to safe, gender-sensitive basic services – and to develop plans for more durable solutions to displacement. As floods in April to June 2018 have forced more people to leave their homes, an immediate step up in the response is essential. © Oxfam International June 2018 This paper was written by Emma Fanning. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Anna Tomson, Eric Kramak from REACH, Anna Coryndon, Francisco Yermo from Oxfam as well as colleagues in Oxfam, Plan International, World Vision, Danish Refugee Council and Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) in its production. -

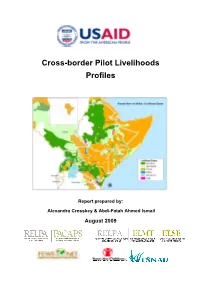

Cross-Border Pilot Livelihoods Profiles

Cross-border Pilot Livelihoods Profiles Report prepared by: Alexandra Crosskey & Abdi-Fatah Ahmed Ismail August 2009 The Pastoral Areas Coordination, Analysis and Policy Support (PACAPS) project is implemented by the Feinstein International Center of Tufts University, under USAID grant number 623‐A‐00‐07‐ 00018‐00. The early warning and early response components of the project are supported by FEG Consulting. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development, the United States Government or Tufts University. Contents Foreword …………………………………..…………………………….……………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………..……………………………………….……….. 4 Section 1: How to Use the Cross‐border Profiles ………………………..………….…………..………… 6 1. Understanding Cross‐border Livelihoods ………………………..………………………………. 6 2. Early Warning ……………………………………….………………………………………..……………….. 6 a. Projected Outcome Analysis for Early Warning ………………………………………..…… 7 b. Early Warning Monitoring ……………………………………..……………………………….… 10 3. Program Development ………………………….……………………….……………………………. 12 a. Intervention Design ………………………………….…………………….……………………….. 12 b. Intervention Timing ………………………………….………………………..……………………. 13 c. Monitoring the Impact of a Project ………………………..…………………….………….. 14 Section 2: Cross‐border Livelihood Profiles …………………………..……………..………………………… 16 1. Introduction ……………………….……………………………………………………………….. 16 2. Filtu‐Dolo Ethiopia – Mandera Kenya Pastoral Livelihood Profile ……………..…..… 17 3. Ethiopia / Somalia -

UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG)

UNITED NATIONS SOMALIA UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) 2nd Quarterly Report 2011 August 2011 UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralised Service Delivery JPLG 2nd Quarterly Report April – June 2011 Participating UN UN Habitat, UNDP, UNICEF, ILO Cluster/Priority United Nations Transitional Plan for Organization(s): and UNCDF. Area: Somalia 2008 -2010 Outcome Two Implementing Ministries of Interior in Somaliland, Puntland and the Transitional Federal Government and target Partner(s): District Councils. Joint Programme Title: UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) Total Approved Joint US$ 37,187,000 Programme Budget: Location: Somaliland, Puntland and south central Somalia SC Approval Date: April 2008 Joint Programme Phase One – 2008 – 2010 and Starting Completion 31/12/ 01/04/2008 Duration: Phase Two 2010 - 2012 Date: Date: 2012 2008 -2011 Through JP pass through with UNDP as AA: Donor Donor Currency USD SIDA 65,000,000 SK 7,030,268 DFID 5,025,000 GBP 7,749,134 Danida 21,000,000 DEK 3,675,212 Norway 6,000,000 NOK 1,002,701 Through JP and bilateral to UNDP EU 7,000,000 Euro 8,908,590 Pass through funds 2009 – 2011 28,365,905 % of Funds Committed: UNDP Italy: $1,800,00; 1,800,000 95% USAID: $1,458,840 1,458,840 Approved: DK:$693,823 693,823 Norway: $723,606 723,606 UNDP TRAC: $100,000 100,000 SIDA: $132,000; 132,000 BPCR: $132,930 132,930 UN Habitat Italy: 866,775 Euro 1,243,400 Parallel Funds 2009 -2011 6,284,599 UNCDF 832,000 TOTAL APPROVED -

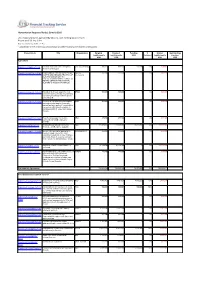

With Funding Status of Each Report As

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2016 List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 23-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R3) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD Agriculture SOM-16/A/84942/5110 Puntland and Lower Juba Emergency VSF (Switzerland) 998,222 998,222 588,380 59% 409,842 0 Animal Health Support SOM-16/A/86501/15092 PROVISION OF FISHING INPUTS FOR SAFUK- 352,409 352,409 0 0% 352,409 0 YOUTHS AND MEN AND TRAINING OF International MEN AND WOMEN ON FISH PRODUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF FISHING GEARS IN THE COASTAL REGIONS OF MUDUG IN SOMALIA. SOM-16/A/86701/14592 Integrated livelihoods support to most BRDO 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 vulnerable conflict affected 2850 farming and fishing households in Marka district Lower Shabelle. SOM-16/A/86746/14852 Provision of essential livelihood support HOD 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 and resilience building for Vulnerable pastoral and agro pastoral households in emergency, crisis and stress phase in Kismaayo district of Lower Juba region, Somalia SOM-16/A/86775/17412 Food Security support for destitute NRO 499,900 499,900 0 0% 499,900 0 communities in Middle and Lower Shabelle SOM-16/A/87833/123 Building Household and Community FAO 111,805,090 111,805,090 15,981,708 14% 95,823,382 0 Resilience and Response Capacity SOM-16/A/88141/17597 Access to live-saving for population in SHARDO Relief 494,554 494,554 0 0% 494,554 0 emergency and crises of the most vulnerable households in lower Shabelle and middle Shabelle regions, and build their resilience to withstand future shocks. -

Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (Tis+) Program Year Three – Annual Work Plan

TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Revised November 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. Annual Work plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TRANSITION INITIATIVES FOR STABILIZATION PLUS (TIS+) PROGRAM YEAR THREE – ANNUAL WORK PLAN (OCTOBER 1, 2017 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2018) Contract No: AID-623-C-15-00001 Submitted to: USAID | Somalia Prepared by: AECOM International Development DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Year Three - Annual Work Plan | Transition Initiatives for Stabilization Plus (TIS+) Program i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................................. iii Stabilization Context .................................................................................................................................. 5 Goals and Objectives of USAID and TIS+ ............................................................................................... 6 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ -

Study Report an Analysis of Women's Land Rights &Territorial Rights Of

STUDY REPORT AN ANALYSIS OF WOMEN’S LAND RIGHTS & TERRITORIAL RIGHTS OF SOMALI MINORITIES IN SOMALILAND Principal Consultant: Dr. Adam Ismail Smart Consultancy & Training Agency (SCOTRA) Hargeisa, Somaliland May 2016 Page 0 of 47 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................3 LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .............................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................4 Key findings: .............................................................................................................................................. 6 1. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................................8 2. HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY OF SOMALILAND .................................................................................9 3. METHODOLOGY OF THE STUDY .................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Study areas ........................................................................................................................................ 12 3.1 Questionnaire: .................................................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Focus group discussions (FGD):........................................................................................................ -

UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG)

UNITED NATIONS SOMALIA UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) 1st Quarterly Report 2011 FINAL May 2011 UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralised Service Delivery JPLG 1st Quarterly Report January – March 2011 Central Administrations of Somaliland, Puntland and the Transitional Federal Government and target Partner(s): District Councils. Joint Programme Title: UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) Total Approved Joint US$ 37,187,000 Programme Budget: Location: Somaliland, Puntland and south central Somalia SC Approval Date: April 2008 Starting Completion 31/12/ Joint Programme 2008 – 2012 01/04/2008 Date: Date: 12 Duration: 2009 -2010 Through JP pass through with UNDP as AA: Donor Donor Currency USD SIDA 30,000,000 SK 3,813,361 DFID 2,275,000 GBP 3,482,109 Danida 15,000,000 DEK 2,672,511 Norway 6,000,000 NOK 1,002,701 Through JP and bilateral EC to UNDP 5,000,000 Euro 7,350,000 Sub total JP Funds 18,320,682 % of Funds Committed: Parallel Funds 2009 -2011 67% Approved: UNDP Italy: $1,800,00; 1,800,000 USAID: $1,757,428 1,757,428 DK:$693,823 693,823 Norway: $723,606 723,606 UNDP TRAC: $100,000 100,000 SIDA: $132,000; 132,000 BPCR: $132,930 132,930 UNHabitat Italy: 866,775 Euro 1,243,400 Sub total Parallel Funds 5,860,511 UNCDF $832,000 TOTAL APPROVED 2009 – 2010 25,013,704 % of Donor USD committed 75% SIDA 3,813,361 DFID 3,482,109 2009/2011: EC 6,051,447 Funds Disbursed: Danida 87,000 Norway 35,000 UNDP/parallel 2,282,771 % of 50% UNDP/USAID 1,758,428 approved UN Habitat/parallel 587,535 UNCDF 232,500 TOTAL 18,330,151 Delay Expected Duration: 5 years Forecast Final Date: December 2012 6 (Months): 2 UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralised Service Delivery EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this reporting period US$3,248,902 has been disbursed against an annual workplan and budget of US$23.3M and of which US$17,456,249 is currently available or committed. -

Fråga-Svar Staden Gaalkacyo I Regionen Mudug Samt Gränsen

2011-10-28 Landinformationsenheten Fråga-svar Staden Gaalkacyo i regionen Mudug samt gränsen mellan Puntland och centrala Somalia Fråga Information önskas om staden Gaalkacyo i Somalia. Gaalkacyo en delad stad där en del tillhör Puntland och den andra de södra och centrala delarna av landet. Vilka delar av staden Gaalkacyo tillhör Puntland? Information önskas även om de olika stadsdelarna i Gaalkacyo. Svar Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) (2010) skriver om gränsen mellan Puntland och södra/centrala Somalia och Somaliland. District and regional administrative jurisdictions of Puntland are lacking clear delineations; yet even the State’s borders with its neighbours from the north and southcentral are still undefined, as a participant from Galkayo recalled: “Let alone the lack of internal jurisdictions, Puntland borders with south-central and Somaliland are not clear. You don’t know where your jurisdiction ends as a State and where the other one starts.” (s. 18) Galkayo – an important crossroads Another area requiring careful attention is the complexity and volatility of Galkayo town and its administrative and social interactions among the various communities living or transiting in this important junction. Galkayo constitutes the epicentre of much of the social, economical and political troubles in the Mudug region as two distinct and often feuding administrations exist. (s. 34) 2 Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit- Somalia (FSNAU) (2010) ger i sin rapport en detaljerad beskrivning av Gaalkacyo (norra och södra Gaalkacyo) vad gäller olika samhällsfunktioner i staden såsom skolor, vägar, sjukhus, skolor och marknader m.m. Information finns också till viss del om i vilken del av staden en viss plats eller byggnad finns.