Gray and Fox Squirrels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Disease Summary

SUMMARY OF DISEASES AFFECTING MICHIGAN WILDLIFE 2015 ABSCESS Abdominal Eastern Fox Squirrel, Trumpeter Swan, Wild Turkey Airsac Canada Goose Articular White-tailed Deer Cranial White-tailed Deer Dermal White-tailed Deer Hepatic White-tailed Deer, Red-tailed Hawk, Wild Turkey Intramuscular White-tailed Deer Muscular Moose, White-tailed Deer, Wild Turkey Ocular White-tailed Deer Pulmonary Granulomatous Focal White-tailed Deer Unspecified White-tailed Deer, Raccoon, Canada Goose Skeletal Mourning Dove Subcutaneous White-tailed Deer, Raccoon, Eastern Fox Squirrel, Mute Swan Thoracic White-tailed Deer Unspecified White-tailed Deer ADHESION Pleural White-tailed Deer 1 AIRSACCULITIS Egg Yolk Canada Goose Fibrinous Chronic Bald Eagle, Red-tailed Hawk, Canada Goose, Mallard, Wild Turkey Mycotic Trumpeter Swan, Canada Goose Necrotic Caseous Chronic Bald Eagle Unspecified Chronic Bald Eagle, Peregrine Falcon, Mute Swan, Redhead, Wild Turkey, Mallard, Mourning Dove Unspecified Snowy Owl, Common Raven, Rock Dove Unspecified Snowy Owl, Merlin, Wild Turkey, American Crow Urate Red-tailed Hawk ANOMALY Congenital White-tailed Deer ARTHROSIS Inflammatory Cooper's Hawk ASCITES Hemorrhagic White-tailed Deer, Red Fox, Beaver ASPERGILLOSIS Airsac American Robin Cranial American Robin Pulmonary Trumpeter Swan, Blue Jay 2 ASPERGILLOSIS (CONTINUED ) Splenic American Robin Unspecified Red-tailed Hawk, Snowy Owl, Trumpeter Swan, Canada Goose, Common Loon, Ring- billed Gull, American Crow, Blue Jay, European Starling BLINDNESS White-tailed Deer BOTULISM Type C Mallard -

Fort Riley Hunting Guide

FORT RILEY HUNTING GUIDE The Fort Riley Military Reservation is located in northeast Kansas between Manhattan and Junction City. About 71,000 of the installation's 101,000 acres are managed for multiple-use, including wildlife management. Hunting is allowed on Fort Riley when compatible with the post's primary mission of military training. Fort Riley has a diverse and abundant wildlife resource, which is a product of the post's good habitat conditions. Native tall-grass prairie is well interspersed with riparian and upland woodlands and shrublands creating diverse habitat conditions. Coupled with this native habitat is almost 1,600 acres of land leased for agricultural crop production on the installation's perimeter boundary. Another 700 acres of wildlife food plots, ranging in size from 1/2 to 15 acres, are planted in the interior of the Post each year. Nine principal game species are available to the Fort Riley hunter: bobwhite quail, ring-necked pheasant, greater prairie-chicken, mourning dove, wild turkey, white-tailed deer, elk, cottontail rabbit and fox squirrel. In addition to these species, good populations of raccoon, bobcat and coyote exist on Post. Waterfowl hunting opportunities can be fantastic along the rivers when the ponds and shallow water wetland areas start freezing over, as well as most Central Flyway "puddle" ducks can be found on Fort Riley's numerous ponds and lakes during the fall migration. REGULATIONS On Fort Riley, all State of Kansas and federal hunting regulations (bag limits, season lengths, hunting hours, methods of take, etc.) are in force unless otherwise noted in the Fort Riley Hunting and Fishing Regulations, FR Reg. -

El Dorado Wildlife Area Newsletter 11-20-2014

El Dorado Wildlife Area News Area News – Fall 2014 2014/2015 Hunting Outlook: Upland Birds: The fall hunting outlook for quail on the area is fair. Hunters should see quail numbers that are again increased as compared to last fall. Quail production in recent years (2007-2010) was believed to have been hampered by heavy rains, cool temperatures, and significant flooding during the critical reproductive months of May, June, and July. The 2011 and 2012 reproductive seasons however were notably different. Rather than too much moisture and associated cool temperatures, both years were marked with record breaking excessive heat and drought. Quail production during those years is believed to have suffered as well. More moderate weather conditions in 2013 and 2014 are believed to have resulted in improved production, as several coveys were observed or reported early this fall, but current quail populations remain below levels observed during 2005 and 2006 when quail populations were very good. Within most habitat areas, natural vegetation and area crops should provide good food and cover conditions for wildlife, including quail, and should help to sustain breeding populations into next spring. The wildlife area lies outside the primary range of ring-necked pheasant. Hunters occasionally encounter pheasants on the area, but numbers are low. Male bobwhite. Waterfowl: The fall hunting outlook for waterfowl on the area is fair. Waterfowl populations are reported to remain strong following another good production year within breeding habitats to the north. Habitat conditions however here are not nearly as strong as those experienced last year. Abundant precipitation and a slight flood in June kept lake levels full, or nearly so, for much of the summer. -

Invasion, Damage, and Control Options for Eastern Fox Squirrels

Invasion, Damage, and Control Options for Eastern Fox Squirrels Sara K. Krause, Douglas A. Kelt, and Dirk H. Van Vuren Dept. of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology, University of California, Davis, California ABSTRACT: Fox squirrels are an emerging urban, suburban, and agricultural vertebrate pest in California. They cause a diversity of damage to vegetation and property. Multiple introductions of fox squirrels into California have led to a rapid expansion of their range in the state. Fox squirrels at the University of California, Davis increased from none to an estimated 1,609 between 2001 and 2009. Damage due to the dense population of fox squirrels is increasing. There are several population control options available, but social considerations may limit the viable options to non-lethal methods. This paper provides an overview of the impacts of the introduced fox squirrel in California and on the University of California, Davis campus. KEY WORDS: damage, efficacy, fox squirrel, GonaCon™, Sciurus niger, wildlife birth control, wildlife contraception Proc. 24th Vertebr. Pest Conf. (R. M. Timm and K. A. Fagerstone, Eds.) Published at Univ. of Calif., Davis. 2010. Pp. 29-31. INTRODUCTION km/year (King 2004). In the San Francisco Bay area, we Fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) are found throughout the have seen them in nearly all city and county parks, United States in urban, suburban, rural, and wild areas. educational campuses, open space preserves, state parks, They are native to the eastern and southern United States, and national recreation areas. Populations within as well as some areas of the southwestern United States. California occur along the coast from Sonoma County to They have been introduced to many areas of the western San Diego County, and inland from Lake and El Dorado United States. -

Tree Squirrels There Is Undoubtedly No Other Animal That Has Developed Such a Love-Hate Relationship Around Our Homes and Gardens As That of Tree Squirrels

Tree Squirrels There is undoubtedly no other animal that has developed such a love-hate relationship around our homes and gardens as that of tree squirrels. The eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) are the two species of tree squirrels found in Louisiana. Depending upon your locality, there are two subspecies of gray squirrels and three subspecies of fox squirrels that can be encountered in our state. The nominate race of the eastern gray squirrel occurs in the northwestern por- tion of Louisiana while the darker subspecies know as S. c. fuliginosus occurs in our more southern par- ishes. Throughout the central and northern parishes, specimens tend to show intermediate color charac- teristics between the two subspecies. Eastern gray eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) squirrels regardless of their origin are often referred to as simply gray or cat squirrels. S. n. ludovicianus. These animals are characterized as the largest of all subspecies with a massive skull The three subspecies of fox squirrels found in and slightly paler coloration than the more eastern our state vary drastically in size and color. The subspecies. The bottomland hardwood forests of the western one-third of Louisiana is occupied by Tensas, Mississippi, and Atchafalaya floodplains in the eastern and central-southern portions of the state are home to the smaller, darker subspecies S. n. sub- auratus. Melanistic or black individuals are so com- mon in this subspecies that in local populations, they often outnumber the normal color phase. Areas east of the Mississippi River into the Florida parishes are home to the well-marked race of fox squirrels known as S. -

Life History Account for Eastern Fox Squirrel

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group EASTERN FOX SQUIRREL Sciurus niger Family: SCIURIDAE Order: RODENTIA Class: MAMMALIA M078 Written by: G. Hoefler, J. Harris Reviewed by: H. Shellhammer Edited by: R. Duke, S. Granholm CWHR Staff 2013 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The eastern fox squirrel is an introduced species with many localized populations in urban areas and nearby rural settings. Reported from San Mateo, Merced, and Ventura cos. (Ingles 1965, Wolf and Roest 1971), and Santa Clara and Santa Cruz cos. (Gilroy 1980). Also believed to occur in Ventura and Los Angeles cos., and from Yolo, Napa and Sonoma cos. south to San Benito, Fresno and Monterey cos., west of the Sierra Nevada foothills. The eastern fox squirrel is common in urban and orchard-vineyard habitats, and in eucalyptus groves. Individuals are moving into the edges of valley foothill riparian, redwood, and valley foothill hardwood habitats in Santa Cruz Co. (Gilroy 1980), and possibly elsewhere. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: The eastern fox squirrel eats acorns and a wide variety of other nuts, fruits, and seeds. In Ventura Co., eats wild and domestic agricultural nuts and fruits in summer, eucalyptus seeds in winter (Wolf and Roest 1971, Flyger and Gates 1982). Cover: Uses trees for cover, keeping the tree between squirrel and predator or disturbance. Often remains motionless in order to avoid detection (Flyger and Gates 1982). Reproduction: Uses tree cavity; hollow spheres of leaves also constructed on tree limbs or in the crotches of trees, 8-20 m (26-66 ft) above the ground. -

Emammal Animal Identification Guide

Animal Identification Guide Distinctive Species: White Tailed Deer White tail deer have a tan to reddish-brown coat in the summer and slightly duller color variations during the winter. Males possess antlers during the summer months which are shed during the winter. As the name suggests, white tailed deer have brown tails with a white underside, and often white underbellies. Fawns have reddish coats, and while they are still young have white spots along their backs and sides. They are common in forests; especially ones that have open fields or brush lands, as they feed predominantly on grasses and other vegetation. White-tailed deer are found almost anywhere in the United States. Northern Raccoon Northern raccoons are common almost anywhere in the United States. Their most obvious features are their ringed tails, white faces, and mask-like patches around the eyes. Northern raccoons have coarse looking fur that usually ranges from black to gray, although brown, red and albino raccoons have also been documented. They are well known as being scavengers, and therefore can live in almost any environment that has water and some sort of shelter. They are extremely curious animals and close-up pictures of raccoon faces are common on camera-traps. Virginia Opossum Virginia opossums, a predominantly nocturnal scavenging species native to the southern United States, sport a white head and predominant long, furless pink tail. These opossums have scruffy looking gray body fur, as well as small, leathery ears and a pointed, pink snout. Virginia opossums are often found in forests and woodlands, but due to their scavenging nature are also found in urban areas as well. -

TREE SQUIRRELS in WISCONSIN: Benefits and Problems

G3522 TREE SQUIRRELS IN WISCONSIN: Benefits and Problems Five species of tree squirrels live in Wisconsin: the gray squirrel, fox squirrel, red squirrel, and two species of flying squirrel. All five are popular with people who enjoy watching wildlife, although flying squirrels, because of their nocturnal habits, are rarely seen. As abundant animals low in the food chain, squirrels are important prey species for many mammalian and avian predators. Gray and fox squirrels are popular small-game animals. Squirrels also raid gardens, fields and birdfeeders, FOX SQUIRREL invade houses and other buildings, cause power (Sciurus niger) outages and create other mischief. The fox squirrel is the largest tree squirrel in This bulletin will introduce Wisconsin’s tree squirrels Wisconsin. It is 20 to 22 inches long, including the and describe various management techniques. tail, and weighs 24 to 32 ounces. It gets its name from its rusty brown coat, which is very similar to the GRAY SQUIRREL hair color of a fox. The underside is pale yellow or (Sciurus carolinensis) orange-brown. Color variations are common and may even occur within the same woodlot. The fox The gray squirrel is 18 to 21 inches long, including its squirrel’s “grizzled” rusty brown appearance and size 8- to 10-inch tail, and weighs from 16 to 28 ounces. makes it easy to distinguish from a gray squirrel. Its The gray squirrel derives its name from its grayish brown and gray tail is very fluffy and lacks white- coat, which may vary from black to white. The black tipped hairs. The ears of a fox squirrel are rounded color phase or a golden-yellow “Lady Isabella” gray and shorter and wider than those of a gray squirrel. -

Texas Wildlife Identification Guide

TEXAS WILDLIFE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE A guide to game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife of Texas. INTRODUCTION Texas game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife are important for many reasons. They provide countless hours of viewing and recreational opportunities. They benefit the Texas economy through hunting and “nature tourism” such as birdwatching. Commercial businesses that provide birdseed, dry corn and native landscaping may be devoted solely to attracting many of the animals found in this book. Local hunting and trapping economies, guiding operations and hunting leases have prospered because of the abun- dance of these animals in Texas. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department benefits because of hunting license sales, but it uses these funds to research, manage and protect all wildlife populations – not just game animals. Game animals provide humans with cultural, social, aesthetic and spiritual pleasures found in wildlife art, taxidermy and historical artifacts. Conservation organiza- tions dedicated to individual species such as quail, turkey and deer, have funded thousands of wildlife projects throughout North America, demonstrating the mystique game animals have on people. Animals referenced in this pocket guide exist because their habitat exists in Texas. Habitat is food, cover, water and space, all suitably arranged. They are part of a vast food chain or web that includes thousands more species of wildlife such as the insects, non-game animals, fish and i rare/endangered species. Active management of wild landscapes is the primary means to continue having abundant populations of wildlife in Texas. Preservation of rare and endangered habitat is one way of saving some species of wildlife such as the migratory whooping crane that makes Texas its home in the winter. -

Chapter W-3 - Furbearers and Small Game, Except Migratory Birds

09/01/2021 CHAPTER W-3 - FURBEARERS AND SMALL GAME, EXCEPT MIGRATORY BIRDS Index Page ARTICLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS #300 Definitions 1 #301 License Fees 1 #302 Hours 2 #303 Manner of Take 2 #304 License Requirements 5 #305 Evidence of Sex/Species 5 ARTICLE II SMALL GAME SEASON DATES, UNITS (AS DESCRIBED IN CHAPTER O OF THESE REGULATIONS), BAG AND POSSESSION LIMITS, LIMITED LICENSES AND PERMITS #306 Cottontail Rabbit, Snowshoe Hare, White-tailed & Black-tailed 6 jackrabbit #307 Abert's Squirrels 6 #308 Fox Squirrel and Pine Squirrels 6 #309 Wyoming (Richardson's) ground squirrel, black-tailed, white-tailed, 6 and Gunnison prairie dogs #310 Common Snapping Turtle 7 #311 Marmot 7 #312 Prairie Rattlesnake 7 #313 Dusky (Blue) Grouse 7 #314 White-tailed Ptarmigan 7 #315 Greater Sage-grouse 8 #316 Gunnison Sage-grouse 8 #317 Mountain Sharp-tailed Grouse 8 #318 Chukar Partridge 9 #319 Pheasant 9 #320 Quail (Northern Bobwhite, Scaled, Gambel's) 9 #321 Greater Prairie-Chicken 9 #322 Wild Turkey 10 #322.5 Ranching for Wildlife - Turkey 17 #323 Mink, pine marten, badger, gray fox, red fox, swift fox, raccoon, 20 ring-tailed cat, striped skunk, western spotted skunk, long-tailed weasel, short-tailed weasel, opossum and muskrat #324 Bobcat 20 #325 Coyote 20 #326 Beaver 20 Basis and Purpose 22 Statement CHAPTER W-3 - FURBEARERS and SMALL GAME, EXCEPT MIGRATORY BIRDS ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #300 - Definitions A. "Canada Lynx Recovery Area" means the area of the San Juan and Rio Grande National Forests and associated lands above 9,000 feet extending west from a north-south line passing through Del Norte and east from a north-south line passing through Dolores and from the New Mexico state line north to the Gunnison basin (including Taylor Park east to the Collegiate Range). -

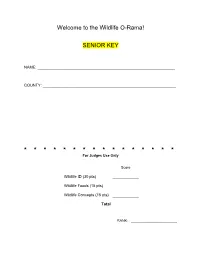

2017 District O-Rama Scorecard SR ANSWERS.Pdf

Welcome to the Wildlife O-Rama! SENIOR KEY NAME: _______________________________________________________________ COUNTY: _____________________________________________________________ * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * For Judges Use Only Score Wildlife ID (30 pts) Wildlife Foods (15 pts) Wildlife Concepts (15 pts) Total RANK: _______________________ Wildlife Identification Mississippi Alluvial Plain & Urban MATCHING: Identify the wildlife species represented by the numbered item on the table and write the letter of the wildlife species in the blank. Answers can be repeated. 1. 16. A. American bittern B. American black duck 2. 17. C. American robin D. American wigeon 3. 18. E. Big brown bat F. Black bear 4. 19. G. Bluegill H. Blue-winged teal 5. 20. I. Bobcat J. Canada goose 6. 21. K. Common nighthawk L. Coyote 7. 22. M. Eastern box turtle N. Eastern bluebird 8. 23. O. Eastern cottontail P. Eastern fox squirrel 9. 24. Q. Eastern gray squirrel R. European starling 10. 25. S. Hairy woodpecker T. House finch 11. 26. U. House sparrow V. House wren 12. 27. W. Largemouth bass X. Mallard 13. 28. Y. Mourning dove Z. Northern flicker 14. 29. AA. Northern pintail BB. Opossum 15. 30. CC. Prothonotary warbler DD. Raccoon EE. Red-eyed vireo FF. Red fox GG. Redhead HH. Rock pigeon II. Ruby-throated hummingbird JJ. Song sparrow KK. White-tailed deer LL. Wood duck 2 Wildlife Foods MULTIPLE CHOICE: Select the best answer and write the letter in the blank. HINT: The foods item represents a food category described in the study materials. The food sample itself may not be eaten by a particular animal. _____31. Which animal commonly eats this food? (soft mast) A. -

Fox Squirrel and Gray Squirrel Associations Within Minimally Disturbed Longleaf Pine Forests

Fox Squirrel and Gray Squirrel Associations within Minimally Disturbed Longleaf Pine Forests L. Mike Conner, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Rt. 2, Box 2324, Newton, GA 31770 J. Larry Landers,1 Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Rt. 2, Box 2324, Newton, GA 31770 William K. Michener, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Rt. 2, Box 2324, Newton, GA 31770 Abstract: Fox squirrels (Sciurus niger) are an important species in longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests. We estimated fox squirrel density within 6 minimally disturbed long- leaf pine strands, examined association between fox and gray squirrels (S. carolinensis), and measured habitat variables at fox and gray squirrel capture sites. Fox squirrel den- sity estimates ranged from 12-19 squirrels/km2 among study areas. Fox squirrel capture sites had higher pine basal area, higher total basal area, higher herbaceous groundcover, and lower woody groundcover than other sites. Gray squirrel capture sites had higher hardwood, oak, and total basal areas; lower pine basal area, higher woody groundcover, and less herbaceous groundcover than other sites. A strong negative association be- tween fox and gray squirrel capture sites appeared related to species-specific habitat preferences. Fox squirrel capture sites had higher pine and lower hardwood basal areas than gray squirrel capture sites. Further, herbaceous groundcover, especially wiregrass (Aristida stricta), dominated fox squirrel capture sites, whereas woody groundcover dominated gray squirrel capture sites. Logistic regression models indicated that pine basal area and herbaceous groundcover were positively related to probability of fox squirrel capture whereas fern groundcover was negatively related to the possibility of fox squirrel capture.