Javascript Allongé, the ``Six'' Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Javascript and the DOM

Javascript and the DOM 1 Introduzione alla programmazione web – Marco Ronchetti 2020 – Università di Trento The web architecture with smart browser The web programmer also writes Programs which run on the browser. Which language? Javascript! HTTP Get + params File System Smart browser Server httpd Cgi-bin Internet Query SQL Client process DB Data Evolution 3: execute code also on client! (How ?) Javascript and the DOM 1- Adding dynamic behaviour to HTML 3 Introduzione alla programmazione web – Marco Ronchetti 2020 – Università di Trento Example 1: onmouseover, onmouseout <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>Dynamic behaviour</title> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0"> </head> <body> <div onmouseover="this.style.color = 'red'" onmouseout="this.style.color = 'green'"> I can change my colour!</div> </body> </html> JAVASCRIPT The dynamic behaviour is on the client side! (The file can be loaded locally) <body> <div Example 2: onmouseover, onmouseout onmouseover="this.style.background='orange'; this.style.color = 'blue';" onmouseout=" this.innerText='and my text and position too!'; this.style.position='absolute'; this.style.left='100px’; this.style.top='150px'; this.style.borderStyle='ridge'; this.style.borderColor='blue'; this.style.fontSize='24pt';"> I can change my colour... </div> </body > JavaScript is event-based UiEvents: These event objects iherits the properties of the UiEvent: • The FocusEvent • The InputEvent • The KeyboardEvent • The MouseEvent • The TouchEvent • The WheelEvent See https://www.w3schools.com/jsref/obj_uievent.asp Test and Gym JAVASCRIPT HTML HEAD HTML BODY CSS https://www.jdoodle.com/html-css-javascript-online-editor/ Javascript and the DOM 2- Introduction to the language 8 Introduzione alla programmazione web – Marco Ronchetti 2020 – Università di Trento JavaScript History • JavaScript was born as Mocha, then “LiveScript” at the beginning of the 94’s. -

The Elinks Manual the Elinks Manual Table of Contents Preface

The ELinks Manual The ELinks Manual Table of Contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................ix 1. Getting ELinks up and running...........................................................................................................1 1.1. Building and Installing ELinks...................................................................................................1 1.2. Requirements..............................................................................................................................1 1.3. Recommended Libraries and Programs......................................................................................1 1.4. Further reading............................................................................................................................2 1.5. Tips to obtain a very small static elinks binary...........................................................................2 1.6. ECMAScript support?!...............................................................................................................4 1.6.1. Ok, so how to get the ECMAScript support working?...................................................4 1.6.2. The ECMAScript support is buggy! Shall I blame Mozilla people?..............................6 1.6.3. Now, I would still like NJS or a new JS engine from scratch. .....................................6 1.7. Feature configuration file (features.conf).............................................................................7 -

Introduction to Javascript

Introduction to JavaScript Lecture 6 CGS 3066 Fall 2016 October 6, 2016 JavaScript I Dynamic programming language. Program the behavior of web pages. I Client-side scripts to interact with the user. I Communicates asynchronously and alters document content. I Used with Node.js in server side scripting, game development, mobile applications, etc. I Has thousands of libraries that can be used to carry out various tasks. JavaScript is NOT Java I Names can be deceiving. I Java is a full-fledged object-oriented programming language. I Java is popular for developing large-scale distributed enterprise applications and web applications. I JavaScript is a browser-based scripting language developed by Netscape and implemented in all major browsers. I JavaScript is executed by the browsers on the client side. JavaScript and other languages JavaScript borrows the elements from a variety of languages. I Object orientation from Java. I Syntax from C. I Semantics from Self and Scheme. Whats a script? I A program written for a special runtime environment. I Interpreted (as opposed to compiled). I Used to automate tasks. I Operates at very high levels of abstraction. Whats JavaScript? I Developed at Netscape to perform client side validation. I Adopted by Microsoft in IE 3.0 (1996). I Standardized in 1996. Current standard is ECMAScript 6 (2016). I Specifications for ECMAScript 2016 are out. I CommonJS used for development outside the browser. JavaScript uses I JavaScript has an insanely large API and library. I It is possible to do almost anything with JavaScript. I Write small scripts/apps for your webpage. -

![NINETEENTH PLENARY MEETING of ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 22 London, United Kingdom September 19-22, 2006 [20060918/22] Version 1, April 17, 2006 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8585/nineteenth-plenary-meeting-of-iso-iec-jtc-1-sc-22-london-united-kingdom-september-19-22-2006-20060918-22-version-1-april-17-2006-1-638585.webp)

NINETEENTH PLENARY MEETING of ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 22 London, United Kingdom September 19-22, 2006 [20060918/22] Version 1, April 17, 2006 1

NINETEENTH PLENARY MEETING OF ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 22 London, United Kingdom September 19-22, 2006 [20060918/22] Version 1, April 17, 2006 1. OPENING OF PLENARY MEETING (9:00 hours, Tuesday, September 19) 2. CHAIRMAN'S REMARKS 3. ROLL CALL OF DELEGATES 4. APPOINTMENT OF DRAFTING COMMITTEE 5. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 6. REPORT OF THE SECRETARY 6.1 SC 22 Project Information 6.2 Proposals for New Work Items within SC 22 6.3 Outstanding Actions From the Eighteenth Plenary of SC 22 Page 1 of 7 JTC 1 SC 22, 2005 Version 1, April 14, 2006 6.4 Transition to ISO Livelink 6.4.1 SC 22 Transition 7. ACTIVITY REPORTS 7.1 National Body Reports 7.2 External Liaison Reports 7.2.1 ECMA International (Rex Jaeschke) 7.2.2 Free Standards Group (Nick Stoughton) 7.2.2 Austin Joint Working Group (Nick Stoughton) 7.3 Internal Liaison Reports 7.3.1 Liaison Officers from JTC 1/SC 2 (Mike Ksar) 7.3.2 Liaison Officer from JTC 1/SC 7 (J. Moore) Page 2 of 7 JTC 1 SC 22, 2005 Version 1, April 14, 2006 7.3.3 Liaison Officer from ISO/TC 37 (Keld Simonsen) 7.3.5 Liaison Officer from JTC 1 SC 32 (Frank Farance) 7.4 Reports from SC 22 Subgroups 7.4.1 Other Working Group Vulnerabilities (Jim Moore) 7.4.2 SC 22 Advisory Group for POSIX (Stephen Walli) 7.5 Reports from JTC 1 Subgroups 7.5.1 JTC 1 Vocabulary (John Hill) 7.5.2 JTC 1 Ad Hoc Directives (John Hill) 8. -

Proposal to Refocus TC39-TG1 on the Maintenance of the Ecmascript, 3 Edition Specification

Proposal to Refocus TC39-TG1 On the Maintenance of the ECMAScript, 3rd Edition Specification Submitted by: Yahoo! Inc. Microsoft Corporation Douglas Crockford Pratap Lakshman & Allen Wirfs-Brock Preface We believe that the specification currently under development by TC39-TG1 as ECMAScript 4 is such a radical departure from the current standard that it is essentially a new language. It is as different from ECMAScript 3rd Edition as C++ is from C. Such a drastic change is not appropriate for a revision of a widely used standardized language and cannot be justified in light of the current broad adoption of ECMAScript 3rd Edition for AJAX style web applications. We do not believe that consensus can be reach within TC39-TG1 based upon its current language design work. However, we do believe that an alternative way forward can be found and submit this proposal as a possible path to resolution. Proposal We propose that the work of TC39-TG1 be reconstituted as two (or possibly three) new TC39 work items as follows: Work item 1 – On going maintenance of ECMAScript, 3rd Edition. In light on the broad adoption of ECMAScript, 3rd Edition for web browser based applications it is clear that this language will remain an important part of the world-wide-web infrastructure for the foreseeable future. However, since the publication of the ECMAScript, 3rd Edition specification in 1999 there has been feature drift between implementations and cross-implementation compatibility issues arising from deficiencies and ambiguities in the specification. The purpose of this work item is to create a maintenance revision of the specification (a 4th Edition) that focuses on these goals: Improve implementation conformance by rewriting the specification to improve its rigor and clarity, and by correcting known points of ambiguity or under specification. -

CS 0449: Introduction to Systems Software

CS 0449: Introduction to Systems Software Jonathan Misurda Computer Science Department University of Pittsburgh [email protected] http://www.cs.pitt.edu/∼jmisurda Version 3, revision 1 Last modified: July 27, 2017 at 1:33 P.M. Copyright © 2017 by Jonathan Misurda This text is meant to accompany the course CS 0449 at the University of Pittsburgh. Any other use, commercial or otherwise, is prohibited without permission of the author. All rights reserved. Java is a registered trademark of Oracle Corporation. This reference is dedicated to the students of CS 0449, Fall 2007 (2081). Their patience in dealing with a changing course and feedback on the first version of this text was greatly appreciated. Contents Contents i List of Figures v List of Code Listings vii Preface ix 1 Pointers 1 1.1 Basic Pointers . 2 1.1.1 Fundamental Operations . 2 1.2 Passing Pointers to Functions . 4 1.3 Pointers, Arrays, and Strings . 5 1.3.1 Pointer Arithmetic . 6 1.4 Terms and Definitions . 7 2 Variables: Scope & Lifetime 8 2.1 Scope and Lifetime in C . 9 2.1.1 Global Variables . 11 2.1.2 Automatic Variables . 12 2.1.3 Register variables . 13 2.1.4 Static Variables . 13 2.1.5 Volatile Variables . 16 2.2 Summary Table . 17 2.3 Terms and Definitions . 17 ii Contents 3 Compiling & Linking: From Code to Executable 19 3.1 The Stages of Compilation . 19 3.1.1 The Preprocessor . 20 3.1.2 The Compiler . 21 3.1.3 The Linker . 22 3.2 Executable File Formats . -

International Standard Iso/Iec 9075-2

This is a previewINTERNATIONAL - click here to buy the full publication ISO/IEC STANDARD 9075-2 Fifth edition 2016-12-15 Information technology — Database languages — SQL — Part 2: Foundation (SQL/Foundation) Technologies de l’information — Langages de base de données — SQL — Partie 2: Fondations (SQL/Fondations) Reference number ISO/IEC 9075-2:2016(E) © ISO/IEC 2016 ISO/IEC 9075-2:2016(E) This is a preview - click here to buy the full publication COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO/IEC 2016, Published in Switzerland All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form orthe by requester. any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of Ch. de Blandonnet 8 • CP 401 ISOCH-1214 copyright Vernier, office Geneva, Switzerland Tel. +41 22 749 01 11 Fax +41 22 749 09 47 www.iso.org [email protected] ii © ISO/IEC 2016 – All rights reserved This is a preview - click here to buy the full publication ISO/IEC 9075-2:2016(E) Contents Page Foreword..................................................................................... xxi Introduction.................................................................................. xxii 1 Scope.................................................................................... 1 2 Normative references..................................................................... -

Proof/Épreuve

0- W e8 IE -2 V 07 E a3 ) 4 R i 68 P .a /5 -1 D h st 7 e si 75 R it s/ 1 A s. : d -2 rd r rf D rd a da p N a d n o- A d an ta is t /s c/ T n l s g 5 S ta l lo 8 s u a cc eh ( F at 0 /c fa iT ai c INTERNATIONAL . b0 eh a it - s. 43 STANDARD rd a9 a 1- nd f a 4b st // s: tp ht Document management for PDF — 21757-1 Part 1: Use of ISO 32000-2 (PDF 2.0) ISO First edition — ECMAScript PROOF/ÉPREUVE ISO 21757-1:2020(E)Reference number © ISO 2020 ISO 21757-1:2020(E) 0- W e8 IE -2 V 07 E a3 ) 4 R i 68 P .a /5 -1 D h st 7 e si 75 R it s/ 1 A s. : d -2 rd r rf D rd a da p N a d n o- A d an ta is t /s c/ T n l s g 5 S ta l lo 8 s u a cc eh ( F at 0 /c fa iT ai c . b0 eh a it - s. 43 rd a9 a 1- nd f a 4b st // s: tp ht © ISO 2020 All rights reserved. UnlessCOPYRIGHT otherwise specified, PROTECTED or required inDOCUMENT the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. -

Evolution of the Major Programming Languages

COS 301 Programming Languages Evolution of the Major Programming Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics Zuse’s Plankalkül Minimal Hardware Programming: Pseudocodes The IBM 704 and Fortran Functional Programming: LISP ALGOL 60 COBOL BASIC PL/I APL and SNOBOL SIMULA 67 Orthogonal Design: ALGOL 68 UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics (continued) Some Early Descendants of the ALGOLs Prolog Ada Object-Oriented Programming: Smalltalk Combining Imperative and Object-Oriented Features: C++ Imperative-Based Object-Oriented Language: Java Scripting Languages A C-Based Language for the New Millennium: C# Markup/Programming Hybrid Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Genealogy of Common Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Alternate View UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Zuse’s Plankalkül • Designed in 1945 • For computers based on electromechanical relays • Not published until 1972, implemented in 2000 [Rojas et al.] • Advanced data structures: – Two’s complement integers, floating point with hidden bit, arrays, records – Basic data type: arrays, tuples of arrays • Included algorithms for playing chess • Odd: 2D language • Functions, but no recursion • Loops (“while”) and guarded conditionals [Dijkstra, 1975] UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Plankalkül Syntax • 3 lines for a statement: – Operation – Subscripts – Types • An assignment -

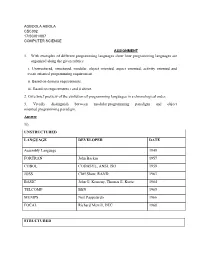

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Secure Coding in Modern C++

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF INFORMATICS Secure coding in modern C++ MASTER'S THESIS Be. Matěj Plch Brno, Spring 2018 MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF INFORMATICS Secure coding in modern C++ MASTER'S THESIS Be. Matěj Plch Brno, Spring 2018 This is where a copy of the official signed thesis assignment and a copy of the Statement of an Author is located in the printed version of the document. Declaration Hereby I declare that this paper is my original authorial work, which I have worked out on my own. All sources, references, and literature used or excerpted during elaboration of this work are properly cited and listed in complete reference to the due source. Be. Matěj Plch Advisor: RNDr. Jifi Kur, Ph.D. i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Jiří Kůr for his valuable guidance and advice. I would also like to thank my parents for their support throughout my studies. ii Abstract This thesis documents how using modern C++ standards can help with writing more secure code. We describe common vulnerabilities, and show new language features which prevent them. We also de• scribe coding conventions and tools which help programmers with using modern C++ features. This thesis can be used as a handbook for programmers who would like to know how to use modern C++ features for writing secure code. We also perform an extensive static analysis of open source C++ projects to find out how often are obsolete constructs of C++ still used in practice. iii Keywords secure coding, modern C++, vulnerabilities, ISO standard, coding conventions, -

Resource Management and Tuples in C∀

Resource Management and Tuples in C8 by Robert Schluntz A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Mathematics in Computer Science Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Robert Schluntz 2017 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract C8 is a modern, non-object-oriented extension of the C programming language. This thesis addresses several critical deficiencies of C, notably: resource management, a limited function- return mechanism, and unsafe variadic functions. To solve these problems, two fundamental language features are introduced: tuples and constructors/destructors. While these features exist in prior programming languages, the contribution of this work is engineering these features into a highly complex type system. C is an established language with a dedicated user-base. An important goal is to add new features in a way that naturally feels like C, to appeal to this core user-base, and due to huge amounts of legacy code, maintaining backwards compatibility is crucial. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Peter Buhr, for all of his help, including reading the many drafts of this thesis and providing guidance throughout my degree. This work would not have been as enjoyable, nor would it have been as strong without Peter’s knowledge, help, and encouragement. I would like to thank my readers, Professors Gregor Richards and Patrick Lam for all of their helpful feedback.