Disentangling Individual Phases in the Hunted Vs. Farmed Meat Supply Chain: Exploring Hunters’ Perceptions in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of Others' Deliberations

CHAPTER FOUR An Evaluation of Others’ Deliberations 4.1 Introduction If ethics is a search for rules of behaviour that can be universally endorsed (Jamieson 1990; Daniels 1979; Rawls 1971), the values underpinning my own deliberation on the issues explored in this book must be compared with the values underlying the deliberation of others. By considering the challenges raised by others’ views, qualified moral veganism might either be revised or, if it survives critique, be corroborated. Though some scholars who work in ani- mal ethics have defended views that are—to a reasonable degree—similar to my own (e.g. Milligan 2010; Kheel 2008; Adams 1990), many people consume animal products where they have adequate alternatives that, in my view, would reduce negative GHIs. This raises the question whether qualified moral vegan- ism overlooks something of importance—the fact that so many people act in ways that are incompatible with qualified moral veganism provokes the follow- ing question in me: Am I missing something? The ambition of this chapter is twofold. Its first aim is to analyse the delib- erations of two widely different groups of people on vegetarianism, veganism, and the killing of animals. By describing the views of others as accurately as I can, I aim to set aside my own thoughts on the matter temporarily—to the extent that doing so is possible—to throw light on where others might be coming from. The second aim of the chapter is to evaluate these views. By doing so, I hope that the reader will be stimulated to reflect upon their own dietary narratives through critical engagement with the views of others. -

Britain's Failing Slaughterhouses

BRITAIN’S FAILING SLAUGHTERHOUSES WHY IT’S TIME TO MAKE INDEPENDENTLY MONITORED CCTV MANDATORY www.animalaid.org.uk INTRODUCTION 4,000 0 SERIOUS BREACHES slaughterhouses SLAUGHTERHOUSES OF ANIMAL filmed were IN FULL COMPLIANCE WELFARE LAW breaking the law WHEN AUDITED More than 4,000 serious breaches of animal welfare laws in British slaughterhouses were reported by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in the two years to August 2016.1 The regulator’s audit showed that not one UK slaughterhouse was in full compliance when the data was analysed in June 2016.2 Yet together, these are just a small sample of the breaches that actually occur inside Britain’s slaughterhouses. We know this because Animal Aid and Hillside Animal Sanctuary have placed fly-on- the-wall cameras inside 15 English slaughterhouses and found how workers behave when they think they are not being watched. Fourteen of the slaughterhouses were breaking animal welfare laws. From small family-run abattoirs to multi-plant Some of these slaughterhouses had installed CCTV, companies, all across the country, and in relation to which shows that the cameras alone do not deter all species, slaughterhouse workers break the law. law-breaking, and that unless the footage is properly Their abuses are both serious and widespread, and monitored, Food Business Operators (FBOs) do are hidden from the regulators. not detect – or do not report – these breaches. It is unknown whether FBOs fail to monitor their When being secretly filmed, workers punched and cameras properly or they monitor them and choose kicked animals in the head; burned them with not to report the abuse. -

Category Slaughterhouse (For Meat and Poultry) / Breaking Location

Supply Chain Disclosure Poultry Upstream Snapshot: December 2018 Published: March 2019 Category Slaughterhouse (for meat and poultry) / Breaking location (for eggs) Location Address Country Chicken Abatedouro Frigorifico Avenida Antonio Ortega nº 3604, Bairro Pinhal , Cabreuva – São Paulo – Brasil Brazil Chicken Agrosul Agroavícola Industrial S.A. Rua Waldomiro Freiberger, 1000 - São Sebastião do Caí, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil Brazil Turkey Agrosuper Chile Condell Sur 411, Quilpué, Valparaiso, Región de Valparaíso, Chile Chile Chicken Agrosuper LTD Camino La Estrella 401, Rancgua, Chile Chile Poultry Animex Foods Sp. z o.o. Sp. k. Morliny Animex Foods Sp. z o.o. Sp. k. Morliny 15, 14-100 Ostróda, Branch of Iława, Poland Poland Chicken Belwood Lowmoor Business Park Kirkby-In-Ashfield, Nottingham NG17 7ER UK Turkey Biegi Foods GmbH Schaberweg 28 61348 Bad Homburg Germany Poultry BODIN LES TERRES DOUCES SAINTE-HERMINE 85210 France Poultry Bodin et Fils ZA Les Terres Douces, Sainte Hermine, France France Chicken BOSCHER VOLAILLES ZA de Guergadic 22530 Mûr de Bretagne France Chicken Boxing County Economic Development Zone Xinsheng Food Co., Ltd. Fuyuan two road, Boxing County Economic Development Zone, Binzhou China Duck Burgaud Parc Activ De La Bloire 42 Rue Gustave Eiffel 85300 France Turkey Butterball - Carthage 411 N Main Street, Carthage, MO 64836 USA Turkey Butterball - Mt. Olive 1628 Garner's Chapel Road, Mt Olive, NC 28365 USA Chicken C Vale - Paloina Av Ariosvaldo Bittencourt, 2000 - Centro - Palotina, PR Brazil Duck Canards d'Auzan -

Broiler Chickens

The Life of: Broiler Chickens Chickens reared for meat are called broilers or broiler chickens. They originate from the jungle fowl of the Indian Subcontinent. The broiler industry has grown due to consumer demand for affordable poultry meat. Breeding for production traits and improved nutrition have been used to increase the weight of the breast muscle. Commercial broiler chickens are bred to be very fast growing in order to gain weight quickly. In their natural environment, chickens spend much of their time foraging for food. This means that they are highly motivated to perform species specific behaviours that are typical for chickens (natural behaviours), such as foraging, pecking, scratching and feather maintenance behaviours like preening and dust-bathing. Trees are used for perching at night to avoid predators. The life of chickens destined for meat production consists of two distinct phases. They are born in a hatchery and moved to a grow-out farm at 1 day-old. They remain here until they are heavy enough to be slaughtered. This document gives an overview of a typical broiler chicken’s life. The Hatchery The parent birds (breeder birds - see section at the end) used to produce meat chickens have their eggs removed and placed in an incubator. In the incubator, the eggs are kept under optimum atmosphere conditions and highly regulated temperatures. At 21 days, the chicks are ready to hatch, using their egg tooth to break out of their shell (in a natural situation, the mother would help with this). Chicks are precocial, meaning that immediately after hatching they are relatively mature and can walk around. -

Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in the Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies

The Cine-Files, Issue 14 (spring 2019) Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies Ece Üçoluk Krane In this article I will consider insights emerging from the field of Animal Studies in relation to a selection of films in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (hereafter TCSM) franchise. By paying close attention to the construction of the animal subject and the human-animal relation in the TCSM franchise, I will argue that the original 1974 film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre II (1986) and the 2003 reboot The Texas Chain Saw Massacre all transgress the human-animal boundary in order to critique “carnism.”1 As such, these films exemplify “posthuman cannibalism,” which I define as a trope that transgresses the human-nonhuman boundary to undermine speciesism and anthropocentrism. In contrast, the most recent installment in the TCSM franchise Leatherface (2017) paradoxically disrupts the human-animal boundary only to re-establish it, thereby diverging from the earlier films’ critiques of carnism. For Communication scholar and animal advocate Carrie Packwood Freeman, the human/animal duality lying at the heart of speciesism is something humans have created in their own minds.2 That is, we humans typically do not consider ourselves animals, even though we may acknowledge evolution as a factual account of human development. Freeman proposes that we begin to transform this hegemonic mindset by creating language that would help humans rhetorically reconstruct themselves as animals. Specifically, she calls for the replacement of the term “human” with “humanimal” and the term “animal” with “nonhuman animal.”3 The advantage of Freeman’s terms is that instead of being mutually exclusive, they are mutually inclusive terms that foreground commonalities between humans and animals instead of differences. -

Dragon and the Phoenix Teacher's Notes.Indd

Usborne English The Dragon and the Phoenix • Teacher’s notes Author: traditi onal, retold by Lesley Sims Reader level: Elementary Word count: 235 Lexile level: 350L Text type: Folk tale from China About the story A dragon and a phoenix live on opposite sides of a magic river. One day they meet on an island and discover a shiny pebble. The dragon washes it and the phoenix polishes it unti l it becomes a pearl. Its brilliant light att racts the att enti on of the Queen of Heaven, and that night she sends a guard to steal it while the dragon and phoenix are sleeping. The next morning, the dragon and phoenix search everywhere and eventually see their pearl shining in the sky. They fl y up to retrieve it, but the pearl falls down and becomes a lake on the ground below. The dragon and the phoenix lie down beside the lake, and are sti ll there today in the guise of Dragon Mountain and Phoenix Mountain. The story is based on The Bright Pearl, a Chinese folk tale. Chinese dragons are typically depicted without wings (although they are able to fl y), and are associated with water and wisdom. Chinese phoenixes are immortal, and do not need to die and then be reborn. They are associated with loyalty and honesty. The dragon and phoenix are oft en linked to the male yin and female yang qualiti es, and in the past, a Chinese emperor’s robes would typically be embroidered with dragons and an empress’s with phoenixes. -

Unhappy Cows and Unfair Competition: Using Unfair Competition Laws to Fight Farm Animal Abuse

UNHAPPY COWS AND UNFAIR COMPETITION: USING UNFAIR COMPETITION LAWS TO FIGHT FARM ANIMAL ABUSE Donna Mo Most farm animals suffer for the entirety of their lives, both on the farm and at the slaughterhouse. While there are state and federal laws designed to protect these animals from abuse, such laws are rarely enforced by the public officials who have the authority to do so. Animal advocacy groups have taken matters into their own hands by utilizing state unfair competition laws, including CaliforniaBusiness and Professions Code section 17200. Section 17200 is a state version of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which prohibits unfair and deceptive business practices. Such "Little FTC Acts" exist in every state and are, for the most part, very similar. Thus, while this Comment focuses on section 17200, its reasoning is applicable to other states as well. This Comment explores the many ways in which unfair competition laws, namely section 17200, may be employed to protect farm animals. The passage of Proposition 64 by California voters in November 2004, which added a standing requirement for section 17200 plaintiffs, has curtailed the scope of the statute significantly. This Comment argues, however, that section 17200 can still be used to protect farm animals, through the use of humane competitors and individual consumers as plaintiffs. INTRO DU CTION .................................................................................................................. 1314 1. THE NEED FOR PRIVATE ENFORCEMENT .................................................................... 1318 A . The Lack of Public Enforcem ent ...................................................................... 1318 1. Cruelty in the Slaughterhouse ................................................................... 1318 2. C ruelty on the Farm ................................................................................... 1319 II. AN OVERVIEW OF UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW USAGE: CALIFORNIA BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONS CODE SECTION 17200 ................................................ -

Reasonable Humans and Animals: an Argument for Vegetarianism

BETWEEN THE SPECIES Issue VIII August 2008 www.cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ Reasonable Humans and Animals: An Argument for Vegetarianism Nathan Nobis Philosophy Department Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA USA www.NathanNobis.com [email protected] “It is easy for us to criticize the prejudices of our grandfathers, from which our fathers freed themselves. It is more difficult to distance ourselves from our own views, so that we can dispassionately search for prejudices among the beliefs and values we hold.” - Peter Singer “It's a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” - Harriet Beecher Stowe In my experience of teaching philosophy, ethics and logic courses, I have found that no topic brings out the rational and emotional best and worst in people than ethical questions about the treatment of animals. This is not surprising since, unlike questions about social policy, generally about what other people should do, moral questions about animals are personal. As philosopher Peter Singer has observed, “For most human beings, especially in modern urban and suburban communities, the most direct form of contact with non-human animals is at mealtimes: we eat Between the Species, VIII, August 2008, cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ 1 them.”1 For most of us, then, our own daily behaviors and choices are challenged when we reflect on the reasons given to think that change is needed in our treatment of, and attitudes toward, animals. That the issue is personal presents unique challenges, and great opportunities, for intellectual and moral progress. Here I present some of the reasons given for and against taking animals seriously and reflect on the role of reason in our lives. -

Pigs, Products, Prototypes and Performances

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 5 & 6 SEPTEMBER 2013, DUBLIN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, DUBLIN, IRELAND ZOOCENTRIC DESIGN: PIGS, PRODUCTS, PROTOTYPES AND PERFORMANCES Seaton BAXTER 1 and Fraser BRUCE 2 1 The Centre for the Study of Natural Design, DJCAD, University of Dundee 2 Product Design, DJCAD, University of Dundee ABSTRACT This paper is concerned with how we apply design to our association with other non-human animals. It exemplifies this with the domestication and current use of the pig (Sus domesticus). After a brief review of the process of domestication, the paper looks at modern production and the increase in concerns for animal health, welfare and performance and the link to food for human consumption. The paper elaborates on the extreme nature of intensive pig production systems and the role that design plays in their operations. It points out the prototypical nature of the modern pigs’ evolution and the means by which man contributes his own prototypes to these changes. It pays some attention to the often conflicting concerns of efficient production and animal welfare. It exemplifies this in a brief study of 2 design products - floor systems and feeding systems, and through the use of a Holmesian type puzzle, shows the complex interrelationships of the two products. The paper emphasises the need for designers to avoid extreme anthropomorphism, adopt whenever possible a zoocentric and salutogenic (health oriented) approach and remain fully aware that all technical decisions are also likely to be ethical decisions. The paper concludes with some suggestions of what might be incorporated into the curriculum of product design courses. -

Curiosity Killed the Bird: Arbitrary Hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia

Cotinga30-080617:Cotinga 6/17/2008 8:11 AM Page 12 Cotinga 30 Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Received 11 December 2006; final revision accepted 4 October 2007 Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15 Durante pesquisas ecológicas na fronteira agrícola do norte do Mato Grosso, foram registrados vários casos de abate de harpias Harpia harpyja por caçadores locais, motivados por simples curiosidade ou sua intolerância ao suposto perigo para suas criações domésticas. A caça arbitrária de harpias não parece ser muito freqüente, mas pode ter um impacto relativamente grande sobre as populações locais, considerando sua baixa densidade, e também para o ecossistema, por causa do papel ecológico da espécie, como um predador de topo. Entre as possíveis estratégias mitigadoras, sugere-se utilizar a harpia como espécie bandeira para o desenvolvimento de programas de conservação na região. With adult female body weights of up to 10 kg, The study was conducted in the municipalities Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja (Fig. 1) are the New of Alta Floresta (09º53’S 56º28’W) and Nova World’s largest raptors, and occur in tropical forests Bandeirantes (09º11’S 61º57’W), in northern Mato from Middle America to northern Argentina4,14,17,22. Grosso, Brazil. Both are typical Amazonian They are relatively sensitive to anthropogenic frontier towns, characterised by immigration from disturbance and are among the first species to southern and eastern Brazil, and ongoing disappear from areas colonised by humans. fragmentation of the original forest cover. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

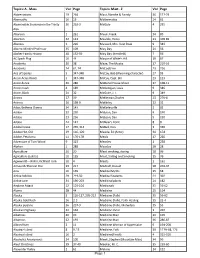

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Research Article WILDMEN in MYANMAR

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 4:53-66 (2015) Research Article WILDMEN IN MYANMAR: A COMPENDIUM OF PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS AND REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE Steven G. Platt1, Thomas R. Rainwater2* 1 Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, Office Block C-1, Aye Yeik Mon 1st Street, Hlaing Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2 Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, P.O. Box 596, Georgetown, SC 29442, USA ABSTRACT. In contrast to other countries in Asia, little is known concerning the possible occurrence of undescribed Hominoidea (i.e., wildmen) in Myanmar (Burma). We here present six accounts from Myanmar describing wildmen or their sign published between 1910 and 1972; three of these reports antedate popularization of wildmen (e.g., yeti and sasquatch) in the global media. Most reports emanate from mountainous regions of northern Myanmar (primarily Kachin State) where wildmen appear to inhabit montane forests. Wildman tracks are described as superficially similar to human (Homo sapiens) footprints, and about the same size to almost twice the size of human tracks. Presumptive pressure ridges were described in one set of wildman tracks. Accounts suggest wildmen are bipedal, 120-245 cm in height, and covered in longish pale to orange-red hair with a head-neck ruff. Wildmen are said to utter distinctive vocalizations, emit strong odors, and sometimes behave aggressively towards humans. Published accounts of wildmen in Myanmar are largely based on narratives provided by indigenous informants. We found nothing to indicate informants were attempting to beguile investigators, and consider it unlikely that wildmen might be confused with other large mammals native to the region.