Cracked Nipples and Moist Wound Healing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breastfeeding Complications (Women) 2001.04

05/2015 602 Breastfeeding Complications or Potential Complications (Women) Definition/Cut-off Value A breastfeeding woman with any of the following complications or potential complications for breastfeeding: Complications (or Potential Complications) Severe breast engorgement Cracked, bleeding or severely sore nipples Recurrent plugged ducts Age ≥ 40 years Mastitis (fever or flu-like symptoms with localized Failure of milk to come in by 4 days postpartum breast tenderness) Tandem nursing (breastfeeding two siblings who are Flat or inverted nipples not twins) Participant Category and Priority Level Category Priority Pregnant Women 1 Breastfeeding Women 1 Justification Severe breast engorgement Severe breast engorgement is often caused by infrequent nursing and/or ineffective removal of milk. This severe breast congestion causes the nipple-areola area to become flattened and tense, making it difficult for the baby to latch-on correctly. The result can be sore, damaged nipples and poor milk transfer during feeding attempts. This ultimately results in diminished milk supply. When the infant is unable to latch-on or nurse effectively, alternative methods of milk expression are necessary, such as using an electric breast pump. Recurrent plugged ducts A clogged duct is a temporary back-up of milk that occurs when one or more of the lobes of the breast do not drain well. This usually results from incomplete emptying of milk. Counseling on feeding frequency or method or advising against wearing an overly tight bra or clothing can assist. Mastitis Mastitis is a breast infection that causes a flu-like illness accompanied by an inflamed, painful area of the breast - putting both the health of the mother and successful breastfeeding at risk. -

Spectrum of Benign Breast Diseases in Females- a 10 Years Study

Original Article Spectrum of Benign Breast Diseases in Females- a 10 years study Ahmed S1, Awal A2 Abstract their life time would have had the sign or symptom of benign breast disease2. Both the physical and specially the The study was conducted to determine the frequency of psychological sufferings of those females should not be various benign breast diseases in female patients, to underestimated and must be taken care of. In fact some analyze the percentage of incidence of benign breast benign breast lesions can be a predisposing risk factor for diseases, the age distribution and their different mode of developing malignancy in later part of life2,3. So it is presentation. This is a prospective cohort study of all female patients visiting a female surgeon with benign essential to recognize and study these lesions in detail to breast problems. The study was conducted at Chittagong identify the high risk group of patients and providing regular Metropolitn Hospital and CSCR hospital in Chittagong surveillance can lead to early detection and management. As over a period of 10 years starting from July 2007 to June the study includes a great number of patients, this may 2017. All female patients visiting with breast problems reflect the spectrum of breast diseases among females in were included in the study. Patients with obvious clinical Bangladesh. features of malignancy or those who on work up were Aims and Objectives diagnosed as carcinoma were excluded from the study. The findings were tabulated in excel sheet and analyzed The objective of the study was to determine the frequency of for the frequency of each lesion, their distribution in various breast diseases in female patients and to analyze the various age group. -

Common Breastfeeding Questions

Common Breastfeeding Questions How often should my baby nurse? Your baby should nurse 8-12 times in 24 hours. Baby will tell you when he’s hungry by “rooting,” sucking on his hands or tongue, or starting to wake. Just respond to baby’s cues and latch baby on right away. Every mom and baby’s feeding patterns will be unique. Some babies routinely breastfeed every 2-3 hours around the clock, while others nurse more frequently while awake and sleep longer stretches in between feedings. The usual length of a breastfeeding session can be 10-15 minutes on each breast or 15-30 minutes on only one breast; just as long as the pattern is consistent. Is baby getting enough breastmilk? Look for these signs to be sure that your baby is getting enough breastmilk: Breastfeed 8-12 times each day, baby is sucking and swallowing while breastfeeding, baby has 3- 4 dirty diapers and 6-8 wet diapers each day, the baby is gaining 4-8 ounces a week after the first 2 weeks, baby seems content after feedings. If you still feel that your baby may not be getting enough milk, talk to your health care provider. How long should I breastfeed? The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends mothers to breastfeed for 12 months or longer. Breastmilk contains everything that a baby needs to develop for the first 6 months. Breastfeeding for at least the first 6 months is termed, “The Golden Standard.” Mothers can begin breastfeeding one hour after giving birth. -

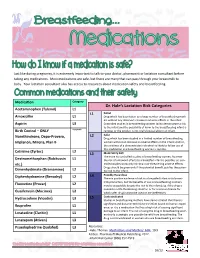

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Nursing Strike

Nursing Strike When a baby who has been nursing happily for some length of time suddenly refuses to latch and feed at the breast, we call it a nursing strike. It can be very upsetting for both a mother and her baby. Nursing strikes happen for many reasons, and we often do not know exactly why. Often it seems as though a baby is trying to communicate Community some form of stress. It is unlikely that your baby is ready to wean, especially if your Breastfeeding baby is less than a year old. Center A nursing strike can last several hours, or several days. While your baby is refusing to 5930 S. 58th Street feed at your breast, use a high-quality pump and remove milk just as often as your (in the Trade Center) Lincoln, NE 68516 baby was nursing. If your breasts get very full and firm, your baby may notice the (402) 423-6402 difference and it may be harder for baby to latch. You may also risk developing a 10818 Elm Street plugged duct. Rockbrook Village Omaha, NE 68144 (402) 502-0617 The following is a list of common reasons that babies refuse the breast, For additional adapted from La Leche League International information: information: www • You changed your deodorant, soap, perfume, lotion, etc. and you smell “different” to your baby. • You have been under stress (such as having extra company, returning to work, traveling, moving, or dealing with a family crisis). • Your baby or toddler has an illness or injury that makes nursing uncomfortable (an ear infection, a stuffy nose, thrush, a cut in the mouth, or sore gums from teething). -

Melasma (1 of 8)

Melasma (1 of 8) 1 Patient presents w/ symmetric hyperpigmented macules, which can be confl uent or punctate suggestive of melasma 2 DIAGNOSIS No ALTERNATIVE Does clinical presentation DIAGNOSIS confirm melasma? Yes A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Monotherapy • Hydroquinone or • Tretinoin TREATMENT Responding to No treatment? See next page Yes Continue treatment © MIMSas required Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. Specifi c prescribing information may be found in the latest MIMS. B94 © MIMS 2019 Melasma (2 of 8) Patient unresponsive to initial therapy MELASMA A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Dual Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin or • Azelaic acid Responding to Yes Continue treatment treatment? as required No A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen • Laser therapy • Dermabrasion B Pharmacological therapy Triple Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin plus • Topical steroid Chemical peels 1 MELASMA • Acquired hyperpigmentary skin disorder characterized by irregular light to dark brown macules occurring in the sun-exposed areas of the face, neck & arms - Occurs most commonly w/ pregnancy (chloasma) & w/ the use of contraceptive pills - Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis are photosensitizing medications, genetic factors, mild ovarian or thyroid dysfunction, & certain cosmetics • Most commonly aff ects Fitzpatrick skin phototypes III & IV • More common in women than in men • Rare before puberty & common in women during their reproductive years • Solar & ©ultraviolet exposure is the mostMIMS important factor in its development Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. -

Breastfeeding Management in Primary Care-FINAL-Part 2.Pptx

Breastfeeding Management in Primary Care Pt 2 Heggie, Licari, Turner May 25 '17 5/15/17 Case 3 – Sore nipples • G3P3 mom with sore nipples, baby 5 days old, full term, Breaseeding Management in yellow stools, output normal per BF log, 5 % wt loss. Primary Care - Part 2 • Mother exam: both nipples with erythema, cracked and scabbed at p, areola mildly swollen, breasts engorged and moderately tender, mild diffuse erythema, no mass. • Baby exam: strong but “chompy” suck, thick ght frenulum aached to p of tongue, with restricted tongue movement- poor lateral tracking, unable to extend tongue past gum line or lower lip, minimal tongue elevaon. May 25, 2017, Duluth, MN • Breaseeding observaon: Baby has deep latch, mom Pamela Heggie MD, IBCLC, FAAP, FABM Addie Licari, MD, FAAFP with good posioning, swallows heard and also Lorraine Turner, MD, ABIHM intermient clicking. Mom reports pain during feeding. Sore cracked nipple Type 1 - Ankyloglossia Sore Nipples § “Normal” nipple soreness is very minimal and ok only if: ü Poor latch § Nipple “tugging” brief (< 30 sec) with latch-on then resolves ü LATCH, LATCH, LATCH § No pain throughout feeding or in between feeds ü Skin breakdown/cracks-staph colonizaon § No skin damage ü Engorgement § Some women are told “the latch looks ok”… but they are in pain and curling their toes ü Trauma from pumping ü § It doesn’t maer how it “looks” … if mom is uncomfortable Nipple Shields it’s a problem and baby not geng much milk…set up for low ü Vasospasm milk supply ü Blocked nipple pore/Nipple bleb § Nipple pain is -

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation

Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 1 Virtual Lactation Support for Breastfeeding Mothers During the Early Postpartum Period Shakeema S. Jordan College of Nursing, East Carolina University Doctor of Nursing Practice Program Dr. Tracey Bell April 30, 2021 Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 2 Notes from the Author I want to express a sincere thank you to Ivy Bagley, MSN, FNP-C, IBCLC for your expertise, support, and time. I also would like to send a special thank you to Dr. Tracey Bell for your support and mentorship. I dedicate my work to my family and friends. I want to send a special thank you to my husband, Barry Jordan, for your support and my two children, Keith and Bryce, for keeping me motivated and encouraged throughout the entire doctorate program. I also dedicate this project to many family members and friends who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all you have done. Through my personal story and the doctorate program journey, I have learned the importance of breastfeeding self-efficacy and advocacy. I understand the impact an adequate support system, education, and resources can have on your ability to reach your individualized breastfeeding goals. Running Head: BREASTFEEDING SUPPORT 3 Abstract Breastmilk is the clinical gold standard for infant feeding and nutrition. Although maternal and child health benefits are associated with breastfeeding, national, state, and local rates remain below target. In fact, 60% of mothers do not breastfeed for as long as intended. During the early postpartum period, mothers cease breastfeeding earlier than planned due to common barriers such as lack of suckling, nipple rejection, painful breast or nipples, latching or positioning difficulties, and nursing demands. -

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start

Breastfeeding Guide Lactation Services Department Breastfeeding: Off to a Great Start Offer to feed your baby: • when you see and hear behaviors that signal readiness to feed. Fussiness and hand to mouth motions may signal hunger. At other times, your baby is asking to be held or changed. He may be showing signs of being over-stimulated or tired. • until satisfied. In the early weeks and months, feeding lengths vary from 10 to 40 minutes per side. Offer both breasts at each feeding. Your baby may not always take the second side. Expect your baby to cluster feed to increase your milk supply, especially when going through growth spurts. • at least every 1 ½ to 3 hours during the day and a little less frequently at night. Time feedings from the start of one feeding to the start of the next. Most mothers are able to produce enough milk and do NOT need to supplement with formula. • using proper positioning. Turn your baby toward you while breastfeeding. With a wide open mouth, she takes in the areola along with the nipple. The cheeks and chin are touching the breast. Expect your baby to pause between suckle bursts. It is okay to gently stimulate her to suckle throughout the feeding. Your baby is getting enough breastmilk IF: • you hear audible swallows when your baby pauses between suckle bursts. You will hear them more often as your milk changes 24 Hours from colostrum to mature milk. st at least 6 feedings • there are 6 or more wet diapers by day 6. This number will 1 1 wet and 1 stool remain fairly constant after the first week. -

Breastfeeding Contraindications

WIC Policy & Procedures Manual POLICY: NED: 06.00.00 Page 1 of 1 Subject: Breastfeeding Contraindications Effective Date: October 1, 2019 Revised from: October 1, 2015 Policy: There are very few medical reasons when a mother should not breastfeed. Identify contraindications that may exist for the participant. Breastfeeding is contraindicated when: • The infant is diagnosed with classic galactosemia, a rare genetic metabolic disorder. • Mother has tested positive for HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome) or has Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). • The mother has tested positive for human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type I or type II (HTLV-1/2). • The mother is using illicit street drugs, such as PCP (phencyclidine) or cocaine (exception: narcotic-dependent mothers who are enrolled in a supervised methadone program and have a negative screening for HIV and other illicit drugs can breastfeed). • The mother has suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease. Breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated when: • The mother is infected with untreated brucellosis. • The mother has an active herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection with lesions on the breast. • The mother is undergoing diagnostic imaging with radiopharmaceuticals. • The mother is taking certain medications or illicit drugs. Note: mothers should be provided breastfeeding support and a breast pump, when appropriate, and may resume breastfeeding after consulting with their health care provider to determine when and if their breast milk is safe for their infant and should be provided with lactation support to establish and maintain milk supply. Direct breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated and the mother should be temporarily isolated from her infant(s) but expressed breast milk can be fed to the infant(s) when: • The mother has untreated, active Tuberculosis (TB) (may resume breastfeeding once she has been treated approximately for two weeks and is documented to be no longer contagious). -

Areola-Sparing Mastectomy: Defining the Risks

COLLECTIVE REVIEWS Areola-Sparing Mastectomy: Defining the Risks Alan J Stolier, MD, FACS, Baiba J Grube, MD, FACS The recent development and popularity of skin-sparing to actual risk of cancer arising in the areola and is pertinent mastectomy (SSM) is a likely byproduct of high-quality to any application of ASM in prophylactic operations. autogenous tissue breast reconstruction. Numerous non- 7. Based on clinical studies, what are the outcomes when randomized series suggest that SSM does not add to the risk some degree of nipple-areola complex (NAC) is preserved of local recurrence.1–3 Although there is still some skepti- as part of the surgical treatment? cism,4 SSM has become a standard part of the surgical ar- mamentarium when dealing with small or in situ breast ANATOMY OF THE AREOLA cancers requiring mastectomy and in prophylactic mastec- In 1719, Morgagni first observed that there were mam- tomy in high-risk patients. Some have suggested that SSM mary ducts present within the areola. In 1837, William also compares favorably with standard mastectomy for Fetherstone Montgomery (1797–1859) described the 6 more advanced local breast cancer.2 Recently, areola- tubercles that would bare his name. In a series of schol- sparing mastectomy (ASM) has been recommended for a arly articles from 1970 to 1974, William Montagna and similar subset of patients in whom potential involvement colleagues described in great detail the histologic anat- 7,8 by cancer of the nipple-areola complex is thought to be low omy of the nipple and areola. He noted that there was or in patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomy.5 For “confusion about the structure of the glands of Mont- ASM, the assumption is that the areola does not contain gomery being referred to as accessory mammary glands glandular tissue and can be treated the same as other breast or as intermediates between mammary and sweat 9 skin. -

Cracked Nipples

UNICEF UK BABY FRIENDLY INITIATIVE GUIDANCE FOR PROVIDING REMOTE CARE FOR MOTHERS AND BABIES DURING THE CORONAVIRUS ( COVID - 19) OUTBREAK GUIDANCE SHEET 5 B ( CHALLENGES ) : SORE , PAINFUL A N D / O R CRACKED NIPPLES Delivering Baby Friendly services at this time can be difficult. However, babies, their mothers and families deserve the very best care we can provide. This document on management of sore, painful and/or cracked nipples is part of a series of guidance sheets designed to help you provide care remotely. THE MOTHER HAS SORE, PAINFUL AND/OR CRACKED NIPPLES ▪ Sore, painful and/or cracked nipples are signs of ineffective positioning and attachment of the baby at the breast. Therefore, revisiting positioning and attachment are the top priorities. ▪ Other causes include restricted tongue movement in the baby (tongue tie) or infection of the breast, e.g. thrush. PREPARING FOR THE CONVERSATION ▪ Plan a mutually agreed appointment with the USEFUL RESOURCES mother and consider using video so that you can watch a feed and see the mother and baby ▪ Breastfeeding assessment tools ▪ Refer to Guidance Sheet 1 before you start (midwives, health visitors, neonatal or ▪ Be aware that parents may be feeling vulnerable and mothers) frightened because of Covid-19, so sensitivity and ▪ Unicef UK support for parents active listening are important overcoming breastfeeding problems ▪ Take the parent’s worries seriously as they can often ▪ Knitted breast and doll (if video call) sense when something is wrong. DURING THE CALL Introduce yourself and confirm consent for the call ▪ Ask the mother to describe her feeding journey so far.