Transform Margins: Development, Controls and Petroleum Systems – an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transform Faults Represent One of the Three

8 Transform faults ransform faults represent one of the three Because of the drift of the newly formed oceanic types of plate boundaries. A peculiar aspect crust away from ridge segments, a relative move- T of their nature is that they are abruptly trans- ment along the faults is induced that corresponds formed into another kind of plate boundary at their to the spreading velocity on both sides of the termination (Wilson, 1965). Plates glide along the ridge. Th e sense of displacement is contrary to fault and move past each other without destruc- the apparent displacement of the ridge segments tion of or creation of new crust. Although crust is (Fig. 8.1b). In the example shown, the transform neither created or destroyed, the transform margin fault is a right-lateral strike-slip fault; if an observer is commonly marked by topographic features like straddles the fault, the right-hand side of the fault scarps, trenches or ridges. moves towards the observer, regardless of which Transform faults occur as several diff erent geo- way is faced. Transform faults end abruptly in a metries; they can connect two segments of growing point, the transformation point, where the strike- plate boundaries (R-R transform fault), one growing slip movement is transformed into a diverging or and one subducting plate boundary (R-T transform converging movement. Th is property gives this fault) or two subducting plate boundaries (T-T fault its name. In the example of the R-R transform transform fault); R stands for mid-ocean ridge, T for fault, the movement at both ends of the fault is deep sea trench ( subduction zone). -

Segmentation of Transform Systems on the East Pacific Rise

Segmentation of transform systems on the East Paci®c Rise: Implications for earthquake processes at fast-slipping oceanic transform faults Patricia M. Gregg Massachusetts Institute of Technology/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Jian Lin Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Deborah K. Smith ABSTRACT Per®t et al., 1996) indicate that ITSCs are Seven of the eight transform systems along the equatorial East Paci®c Rise from 128 N magmatically active, implying that the regions to 158 S have undergone extension due to reorientation of plate motions and have been beneath them are hotter, and thus the litho- segmented into two or more strike-slip fault strands offset by intratransform spreading spheric plate is thinner than the surrounding centers (ITSCs). Earthquakes recorded along these transform systems both teleseismically domains. To explore the effect of segmenta- and hydroacoustically suggest that segmentation geometry plays an important role in how tion on the transform fault thermal structure, slip is accommodated at oceanic transforms. Results of thermal calculations suggest that we use a half-space steady-state lithospheric the thickness of the brittle layer of a segmented transform fault could be signi®cantly cooling model (McKenzie, 1969; Abercrom- reduced by the thermal effect of ITSCs. Consequently, the potential rupture area, and bie and Ekstrom, 2001). The temperature thus maximum seismic moment, is decreased. Using Coulomb static stress models, we within the crust and mantle, T, is de®ned as T 5 k 21/2 illustrate that long ITSCs will prohibit static stress interaction between transform seg- Tmerf [y(2 t) ], where Tm is the mantle ments and limit the maximum possible magnitude of earthquakes on a given transform temperature at depth, assumed to be 1300 8C; k system. -

Reducing Risk Where Tectonic Plates Collide—A Plan to Advance Subduction Zone Science

Reducing Risk Where Tectonic Plates Collide— A Plan to Advance Subduction Zone Science Circular 1428 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover. A U.S. Geological Survey scientist surveys Loowit Creek drainage on Mount St. Helens, part of a long-term project to track sediment erosion and deposition in the channel. View to the north, with Spirit Lake and Mount Rainier in the background. U.S. Geological Survey photograph by Kurt Spicer. Reducing Risk Where Tectonic Plates Collide—A Plan to Advance Subduction Zone Science By Joan S. Gomberg, Kristin A. Ludwig, Barbara A. Bekins, Thomas M. Brocher, John C. Brock, Daniel Brothers, Jason D. Chaytor, Arthur D. Frankel, Eric L. Geist, Matthew Haney, Stephen H. Hickman, William S. Leith, Evelyn A. Roeloffs, William H. Schulz, Thomas W. Sisson, Kristi Wallace, Janet T. Watt, and Anne Wein Circular 1428 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Transform Continental Margins – Part 1: Concepts and Models Christophe Basile

Transform continental margins – Part 1: Concepts and models Christophe Basile To cite this version: Christophe Basile. Transform continental margins – Part 1: Concepts and models. Tectonophysics, Elsevier, 2015, 661, pp.1-10. 10.1016/j.tecto.2015.08.034. hal-01261571 HAL Id: hal-01261571 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01261571 Submitted on 25 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Tectonophysics, 661, p. 1-10, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2015.08.034 Transform continental margins – Part 1: Concepts and models Christophe Basile Address: Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, ISTerre, F-38041 Grenoble, France.cbasile@ujf-grenoble. Abstract This paper reviews the geodynamic concepts and models related to transform continental margins, and their implications on the structure of these margins. Simple kinematic models of transform faulting associated with continental rifting and oceanic accretion allow to define three successive stages of evolution, including intra- continental transform faulting, active transform margin, and passive transform margin. Each part of the transform margin experiences these three stages, but the evolution is diachronous along the margin. Both the duration of each stage and the cumulated strike-slip deformation increase from one extremity of the margin (inner corner) to the other (outer corner). -

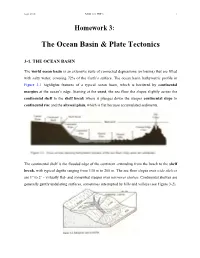

The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics

Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 1 Homework 3: The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world ocean basin is an extensive suite of connected depressions (or basins) that are filled with salty water; covering 72% of the Earth’s surface. The ocean basin bathymetric profile in Figure 3-1 highlights features of a typical ocean basin, which is bordered by continental margins at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, the sea floor the slopes slightly across the continental shelf to the shelf break where it plunges down the steeper continental slope to continental rise and the abyssal plain, which is flat because accumulated sediments. The continental shelf is the flooded edge of the continent -extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The sea floor slopes over wide shelves are 1° to 2° - virtually flat- and somewhat steeper over narrower shelves. Continental shelves are generally gently undulating surfaces, sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3-2). Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 2 The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean, with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While appearing steep in these vertically exaggerated pictures, the bottom slopes of a typical continental slope region are modest angles of 4° to 6°. Continental slope regions adjacent to deep ocean trenches tend to descend somewhat more steeply than normal. Sediments derived from the weathering of the continental material are delivered by rivers and continental shelf flow to the upper continental slope region just beyond the continental shelf break. -

Two Classes of Transform Faults

Two classes of transform faults SrM^r" } Department of Geology, Rutgers >, Newark, New Jersey 07102 ABSTRACT The fault motion is strike slip, and the displacement termina11 s ab- ruptly at both ends. In this model, both transform faults are ridge- A theoretical model and experimental work with cooling wax, as to-trench types (Wilson, 1965). They represent initial cuts in the well as a consideration of some faults that were originally cited as tennis ball (the lithosphere) and thus constitute original or funda- transform faults, have suggested that two classes of transform mental plate boundaries. It is proposed that all transform faults faults exist. They are termed "boundary transform fault" and that represent original or fundamental plate boundaries be called "ridge transform fault." They differ in the degree and manner in "boundary transform faults." which they delineate plate boundaries and probably also in age rel- We can apply the concept of boundary transform fault to the ative to a given plate. South American plate (Fig. 1). The present east boundary of this plate is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Initially, however, the east bound- INTRODUCTION ary was an incipient break in the combined continent of South America and Africa. At that time, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and its Since Wilson's (1965) original definition of transform faults and offsets due to transform faults did not exist. The west boundary of Sykes's (1967) confirmation of the nature of movement along them, the South American plate is the Peru-Chile Trench bordered by the the term "transform fault" has come to be applied to such contrast- Andes. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics Introduction Continental Drift Seafloor Spreading Plate Tectonics Divergent Plate Boundaries Convergent Plate Boundaries Transform Plate Boundaries Summary This curious world we inhabit is more wonderful than convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used. Henry David Thoreau Introduction • Earth's lithosphere is divided into mobile plates. • Plate tectonics describes the distribution and motion of the plates. • The theory of plate tectonics grew out of earlier hypotheses and observations collected during exploration of the rocks of the ocean floor. You will recall from a previous chapter that there are three major layers (crust, mantle, core) within the earth that are identified on the basis of their different compositions (Fig. 1). The uppermost mantle and crust can be subdivided vertically into two layers with contrasting mechanical (physical) properties. The outer layer, the lithosphere, is composed of the crust and uppermost mantle and forms a rigid outer shell down to a depth of approximately 100 km (63 miles). The underlying asthenosphere is composed of partially melted rocks in the upper mantle that acts in a plastic manner on long time scales. Figure 1. The The asthenosphere extends from about 100 to 300 km (63-189 outermost part of miles) depth. The theory of plate tectonics proposes that the Earth is divided lithosphere is divided into a series of plates that fit together like into two the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. mechanical layers, the lithosphere and Although plate tectonics is a relatively young idea in asthenosphere. comparison with unifying theories from other sciences (e.g., law of gravity, theory of evolution), some of the basic observations that represent the foundation of the theory were made many centuries ago when the first maps of the Atlantic Ocean were drawn. -

Origin and Models of Oceanic Transform Faults

Tectonophysics 522–523 (2012) 34–54 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Review Article Origin and models of oceanic transform faults Taras Gerya ⁎ Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, Department of Geosciences, Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Mid-ocean ridges sectioned by transform faults represent prominent surface expressions of plate tectonics. A Received 22 March 2011 fundamental problem of plate tectonics is how this pattern has formed and why it is maintained. Gross-scale Received in revised form 30 June 2011 geometry of mid-ocean ridges is often inherited from respective rifted margins. Indeed, transform faults seem Accepted 7 July 2011 to nucleate after the beginning of the oceanic spreading and can spontaneously form at a single straight ridge. Available online 22 July 2011 Both analog and numerical models of transform faults were investigated since the 1970s. Two main groups of analog models were developed: thermomechanical (freezing wax) models with accreting and cooling plates Keywords: – Transform faults and mechanical models with non-accreting lithosphere. Freezing wax models reproduced ridge ridge Mid-ocean ridges transform faults, inactive fracture zones, rotating microplates, overlapping spreading centers and other Analog models features of oceanic ridges. However, these models often produced open spreading centers that are dissimilar Numerical models to nature. Mechanical models, on the other hand, do not accrete the lithosphere and their results are thus only applicable for relatively small amount of spreading. Three main types of numerical models were investigated: models of stress and displacement distribution around transforms, models of their thermal structure and crustal growth, and models of nucleation and evolution of ridge-transform fault patterns. -

On the Thermal Structure of Oceanic Transform Faults 2 Mark D

1 On the thermal structure of oceanic transform faults 2 Mark D. Behn1,*, Margaret S. Boettcher1,2, and Greg Hirth1 3 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA 4 2U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, USA 5 6 7 Abstract: 8 We use 3-D finite element simulations to investigate the upper mantle temperature 9 structure beneath oceanic transform faults. We show that using a rheology that 10 incorporates brittle weakening of the lithosphere generates a region of enhanced mantle 11 upwelling and elevated temperatures along the transform, with the warmest temperatures 12 and thinnest lithosphere predicted near the center of the transform. In contrast, previous 13 studies that examined 3-D advective and conductive heat transport found that oceanic 14 transform faults are characterized by anomalously cold upper mantle relative to adjacent 15 intra-plate regions, with the thickest lithosphere at the center of the transform. These 16 earlier studies used simplified rheologic laws to simulate the behavior of the lithosphere 17 and underlying asthenosphere. Here, we show that the warmer thermal structure 18 predicted by our calculations is directly attributed to the inclusion of a more realistic 19 brittle rheology. This warmer upper mantle temperature structure is consistent with a 20 wide range of geophysical and geochemical observations from ridge-transform 21 environments, including the depth of transform fault seismicity, geochemical anomalies 22 along adjacent ridge segments, and the tendency for long transforms to break into a series 23 of small intra-transform spreading centers during changes in plate motion. 24 Key Words: Oceanic transform faults, mid-ocean ridges, fault rheology, intra-transform 25 spreading centers 26 *Corresponding Author, Dept. -

Earth Hazards of The

Chapter 10: Earth Hazards of the weather • the measure Western US of short-term conditions of the atmosphere such as temperature, wind speed, and Natural hazards are events that result from natural processes and that humidity. have signifi cant impacts on human beings. Extreme weather conditions or geologic activity can cause substantial short-term or long-term changes to our environment. These changes can infl uence crops, homes, infrastructure, and plates • large, rigid pieces of the atmosphere. The 4.6-billion-year-old Earth has experienced many of these the Earth’s crust and upper natural changes, and it has always adjusted accordingly. mantle, which move and interact with one another at their boundaries. The Western United States is located at the junction of three tectonic plates: the Pacifi c, the Juan de Fuca, and the North American. The movement of these plates, even though it occurs on the scale of millimeters per year, makes the Western US a dynamic landscape. The dramatic result is a dizzying assortment subduction • the process of natural hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and volcanoes. by which one plate moves The Pacifi c plate is subducting under Alaska, creating the volcanoes of the under another, sinking into the mantle. Aleutian Islands. The Juan de Fuca plate is subducting under Washington, Oregon, and Northern California, creating the Cascade volcanoes, and the Pacifi c plate is grinding past the North American plate along the famous San Andreas Fault. At the same time, the Basin and Range province, which includes fault • a fracture in the Earth’s nearly the entire state of Nevada, is being stretched and faulted by plate crust in which the rock on one side of the fracture moves movement. -

On the Segmentation of the Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault Zone (Greece) from an Insar Multi-Mode Dataset of the Lefkada 2015 Sequence

remote sensing Article On the Segmentation of the Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault Zone (Greece) from an InSAR Multi-Mode Dataset of the Lefkada 2015 Sequence Nikos Svigkas 1,2,3,* , Simone Atzori 2, Anastasia Kiratzi 1 , Cristiano Tolomei 2 , Andrea Antonioli 2, Ioannis Papoutsis 3, Stefano Salvi 2 and Charalampos (Haris) Kontoes 3 1 Department of Geophysics, Faculty of Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 2 Osservatorio Nazionale Terremoti, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 00143 Roma, Italy 3 Institute of Space Applications and Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens, 15236 Athens, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 July 2019; Accepted: 6 August 2019; Published: 8 August 2019 Abstract: We use Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) to study the Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault Zone (CTF) in the Ionian Sea. The CTF separates continental subduction to the north from oceanic subduction to the south, along the Hellenic Subduction Zone. We exploit a rich multi-modal radar dataset of the most recent major earthquake in the region, the 17 November 2015 Mw 6.4 event, and present new surface displacement results that offer additional constraints on the fault segmentation of the area. Based on this dataset, and by exploiting available information of earthquake relocation, we propose a new rupture process for the 2015 sequence, complementary to those published already. Our modelling includes an additional southern fault segment, oblique to the segment related with the mainshock, which indicates that the CTF structure is more complex than previously believed. Keywords: InSAR; fault segmentation; Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault; seismology 1. Introduction The Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault Zone (CTF) in western Greece (Figure1a), connects two different subducting regimes: subduction of continental lithosphere to the north, with subduction of oceanic lithosphere to the south [1]. -

Plate Boundaries

Transform Boundaries Transform boundaries occur where one segment of rigid lithosphere slides horizontally past another in response to stresses in the lithosphere. The oceanic ridge system is offset (or segmented) by many transform faults. Severe, shallow earthquakes are associated with transform boundaries. Transform faults and fracture zones in the Atlantic Ocean Explanation The San Andreas Fault is a transform fault linking the East Pacific Rise with the Gorda and Juan de Fuca Ridges. Actually an inter-connecting fault system. The west side is moving north relative to the east side. Cause of numerous large shallow earthquakes. Rotating the previous sketch to show the movement of the San Andreas fault Not only do transform faults connect spreading ridges, but also ridges and trenches and two trenches. Two ridges Ridge and trench Two trenches Characteristics of plates . Plates can contain BOTH continental and oceanic crust (North American). They may be largely oceanic (Pacific) or mostly continental (Eurasian). Most plates are bounded by different types of margins (spreading, converging, transform). Plates vary enormously in size (Pacific versus Juan de Fuca). How to recognize Lithospheric Plate Boundaries Volcanic Mid-Ocean Ridges Deep oceanic Trenches Earthquake Zones 1) Along ocean ridges (shallow) 2) Associated with ocean trenches (deep – Benioff zone) 3) Where plates slide past each other (shallow, transform faults) Distribution of Volcanoes 1. Along island arcs 2. Along continental margins Volcanic mid-ocean ridges and trenches Ocean ridges are boundaries where plates are being created, whereas trenches are boundaries where plates are being destroyed (subducted). Location of earthquakes Earthquakes occur along ALL plate boundaries, consequently they provide an ideal demarcation of individual plates.