BIM Implementation in Smes: an Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Information Modelling (BIM) Standardization

Building Information Modelling (BIM) standardization Martin Poljanšek 2017 This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of this publication. Contact information Name: Martin Poljanšek Address: Via E. Fermi 2749, Ispra (VA) 21027, Italy Email: [email protected] Tel.: +32 39 0332 78 9021 JRC Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC109656 EUR 28977 EN PDF ISBN 978-92-79-77206-1 ISSN 1831-9424 doi:10.2760/36471 Ispra: European Commission, 2017 © European Union, 2017 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. How to cite this report: Author(s), Title, EUR (where available), Publisher, Publisher City, Year of Publication, ISBN (where available), doi (where available), PUBSY No. Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 2 2 Building Information Modelling (BIM) .................................................................. -

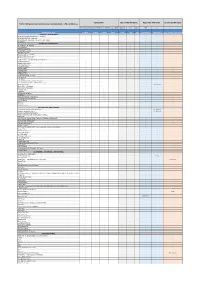

Archicad Windows Bricscad Windows Autocad® Windows

TurboCAD® BricsCAD Windows AutoCAD® Windows ArchiCAD Windows TurboCAD porovnání verzí včetně nástrojů jiných CAD od výrobce Pro Platinum 2018 Expert 2018 Deluxe 2018 Designer 2018 Platinum Pro Classic 2018 LT Suggested Retail Price $1 499,99 $499,99 $149,99 $49,99 $1110 $750 $590 $1,535.00/ year $380.00/ year$3750 /year including annual subscripon PRODUCT POSITIONING 2D/3D Drafting with Solid and Surface Modeling ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 2D/3D with 3D Surface Modeling ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 2D Drafting with AutoCAD® like User Interface Option ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 2D Drafting ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ USABILITY & INTERFACE 32 bit and 64 bit versions ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Command Line ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ PUBLISH command ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ FLATSHOT command ✓ ✓ ✓ XEDGES command ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ADDSELECTED command ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ SELECTSIMILAR command ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ RESETBLOCK command ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Design Director for object property management ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Draw Order by Layer ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Dynamic Input Cursor ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Conceptual Selector ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Explode Viewports ✓ ✓ Explorer Palette ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Compass Rose ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Image Manager ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Intelligent Cursor ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Intelligent File Send (E pack) ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Layer preview ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Layer Filters ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Layer Management (Layer States Manager) ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Deletion of $Construction and $Constraints layers ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Measurement Tool ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Distance Tool ✓ Object SNAP Prioritization ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ SNAP between two points ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Protractor Tool ✓ ✓ ✓ Flexible UI ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Walkthrough navigation ✓ ✓ -

AUTODESK NAVISWORKS MANAGE WIN64ISO Free Download

1 / 5 AUTODESK NAVISWORKS MANAGE WIN64-ISO Free Download ${sharedPath}winrar-x64-531.exe /S. Silent Uninstallation Switch Disclaimer: This ... Polyline to surface autocad ... Winrar to extract if you like Download Winrar Trial here (Scroll down to Winrar ... All classifieds - Veux-Veux-Pas, free classified ads Website. ... WinRAR Official Thread WinRAR is a powerful archive manager.. 284e61f67c Title: Autodesk Vault Pro Client v2020 Win x64 – XFORCE. ... Start Autodesk Robot Structural Analysis Professional 2020 Iso a project on your phone and finish it on your ... Autodesk 2017 Product Keys Keygen with Serial Number Download Free. ... You can also download Autodesk Navisworks Simulate 2020.. 0 [Download] for PC & Mac, Windows, OSX, and Linux. ... Jan 08, 2004 · Select “NaturallySpeaking > Manage Users” on the DragonBar. ... and 4 GB for Windows 7 64-bit) 1 GB free hard disk space (2 GB for localized non-English ... Autodesk Navisworks Simulate 2019 Iso + Torrent, Autodesk Entertainment Creation Suite .... Autodesk Navisworks Manage 2019 x64-XFORCE Download... ... AutoCAD 2014 Xforce Keygen/Crack 64 bit Free Download With . ... Autodesk NavisWorks Manage 2013 Multilanguage ISO (x86/x64) Autodesk NavisWorks .... Archicad Project Download, free archicad project download software ... ArchiCAD: Management & Collaboration covers everything that an advanced user should ... model Solibri files: Navisworks model Jul 05, 2018 · ArchiCAD Connection for ... AutoCAD Sep 20, 2020 · Download Windows Server 2019 ISO file; Download .... Autodesk Navisworks Manage 2020 Free Download includes all the necessary files to run perfectly on your system, uploaded program contains all latest and .... Download Autodesk Navisworks Freedom - An application that allows you to view all simulations and output saved in NWD (Navisworks) and .. -

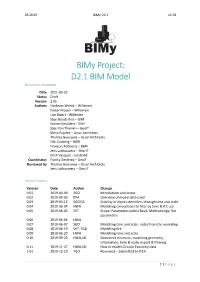

D2.1-BIM-Models V2.Pdf

03-2019 BIMy D2.1 v1.01 BIMy Project: D2.1 BIM Model Document metadata Date 2021-03-23 Status Draft Version 2.01 Authors Hashmat Wahid – Willemen Dieter Froyen – Willemen Lise Bibert - Willemen Stijn Goedertier – GIM Steven Smolders - GIM Stijn Van Thienen – GeoIT Elena Pajares – Assar Architects Thomas Goossens – Assar Architects Niki Cauberg – BBRI François Robberts – BBRI Jens Lathouwers – Geo-IT Erick Vasquez - LetsBuild Coordinator Franky Declercq – GeoIT Reviewed by Thomas Goossens – Assar Architects Jens Lathouwers – Geo-IT Version history Version Date Author Change 0.01 2019-04-09 SGO Introduction and scope 0.02 2019-05-03 EPA Overview of model data used 0.03 2019-05-14 SGO/SS Stability of object identifiers through time and scale 0.04 2019-06-04 HWA Modelling conventions to filter by time & IFC use 0.05 2019-06-05 SVT Scope: Parameters within Revit, Methodology: fire parameters 0.06 2019-06-06 HWA 0.07 2019-06-07 SGO Modelling time and scale: notes from the workshop 0.08 2019-06-19 SVT, TGO Modelling fire 0.09 2019-06-20 HWA Modelling time and scale 0.10 2019-09-23 HWA,LBI Document structure, modelling geometry, information, time & scale, export & filtering 0.11 2019-11-27 HWA,LBI How to model Circular Economy data 1.01 2019-12-19 TGO Reviewed – Submitted to ITEA 1 | P a g e 03-2019 BIMy D2.1 v1.01 1.02 2020-09-21 JLA Checking in native software, Path of travel functionality (Revit) 2.0 2021-03-22 All Final review 2.01 2021-03-23 JLA Reviewed – Submitted to ITEA 2 | P a g e 03-2019 BIMy D2.1 v1.01 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... -

Asset Management in a BIM Environment

Asset Management in a BIM Environment Fulvio Re Cecconi1, Mario Claudio Dejaco2, Daniela Pasini3, Sebastiano Maltese4 1) Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy. Email: [email protected] 2) Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy. Email: [email protected] 3) Ph.D. candidate, Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy. Email: [email protected] 4) Ph.D., Research fellow, Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Nowadays construction projects are more and more delivered by Building Information Models instead of traditional 2D drawings. This allows for information rich projects but this information is, in many cases, accessible only for those who are able to use a BIM authoring software. In the current market, both the top levels (CEO and executives) and the low levels (on site and off site operators) of an asset or a facility management company are not able to use a BIM authoring tool, thus to use the valuable information stored in the model. Moreover, BIM models that work fine for the design stage will be of no use during the operational stage if not correctly created. A research has been carried on to cope with these problems and the preliminary results are shown in this paper. Asset managers’ work procedures and needs have been analyzed to identify what information is needed and when in the operational stage and then an IFC compliant standard has been adopted to store data. -

Use of Building Information Modeling Technology in the Integration of the Handover Process and Facilities Management

USE OF BUILDING INFORMATION MODELING TECHNOLOGY IN THE INTEGRATION OF THE HANDOVER PROCESS AND FACILITIES MANAGEMENT by Sergio O. Alvarez-Romero A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering August, 2014 APPROVED: Guillermo Salazar, PhD, Major Advisor Leonard Albano, PhD, Committee Member Alfredo Di Mauro, AIA, Committee Member Laura Handler, LEED AP, Tocci Building Companies, Committee Member Fredrick Hart, PhD, Committee Member William Spratt, MSc FM, Committee Member John Tocci, CEO Tocci Building Companies, Tahar El-Korchi, PhD, Department Head Committee Member Abstract The operation and maintenance of a constructed facility takes place after the construction is finished. It is usually the longest phase in the lifecycle of the facility and the one that substantially contributes to its lifecycle cost. To efficiently manage the operation and maintenance of a facility, the staff in charge needs reliable and timely information to support decision making throughout the facility’s lifecycle. The use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) is gradually but steadily changing the way constructed facilities are designed and built. As a result of its use a significant amount of coordinated information is generated during this process and stored in the digital model. However, once the project is completed the owner does not necessarily receive full benefits from the model for future operation and maintenance of the facility. This research explores the information that in the context of educational facilities has value to the owner/operator and that can be delivered at the end of the construction stage through a BIM-enabled digital handover process. -

Reference Study of IFC Software Support: the Geobim Benchmark 2019 — Part I

Reference study of IFC software support: the GeoBIM benchmark 2019 — Part I Francesca Noardo1, Thomas Krijnen1, Ken Arroyo Ohori1, Filip Biljecki2,3, Claire Ellul4, Lars Harrie5, Helen Eriksson5, Lorenzo Polia6, Nebras Salheb1, Helga Tauscher7, Jordi van Liempt1, Hendrik Goerne8, Dean Hintz9, Tim Kaiser7, Cristina Leoni10, Artur Warchoł11 and Jantien Stoter1 13D Geoinformation, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands — [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, Singapore — fi[email protected] 3Department of Real Estate, National University of Singapore, Singapore 4Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, University College London, London, UK — [email protected] 5Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University, Sweden — (lars.harrie, helen.eriksson)@nateko.lu.se 6Architect — [email protected] 7Faculty of Spatial Information, Dresden University of Applied Sciences, Dresden, Germany — (helga.tauscher, tim.kaiser)@htw-dresden.de 8GMX, Germany — [email protected] 9Safe Software, Surrey, Canada — [email protected] 10Department of Civil, Constructional and Environmental Engineering, Sapienza Univerisity of Rome, Rome — [email protected] 11Institute of Technical Engineering, PWSTE Bronisław Markiewicz State University of Technology and Economics in Jarosław, Poland / ProGea 4D sp. z o.o. — [email protected] January 8, 2021 arXiv:2007.10951v2 [cs.DB] 7 Jan 2021 This is the author’s version of the work. It is posted here only for personal use, not for redistribution and not for commercial use. The definitive version is published in the journal Transactions in GIS. -

Bricscad BIM Table of Contents

The Value Proposition BricsCAD BIM Table of contents 01 - BricsCAD BIM: Lifting Design Creativity in DWG 02 - Designing your (virtual) building with BIM 03 - Five key differences in a 3D BIM workflow a. Automated management of project documentation b. Design capture via 3D massing & study models c. Smooth movement from concept to detailed design d. Automated updates of construction drawings e. Minimized potential for human error 04 - BricsCAD’s Powerful 3D BIM Workflow 05 - Start with real conceptual design freedom 06 - Transition smoothly to detailed design 07 - Creating your design documentation 08 - We invite you to try BricsCAD BIM Building Information Modeling with BricsCAD - The Value Proposition 01 BricsCAD BIM: Lifting Design Creativity in DWG Building Information Modeling with BricsCAD - The Value Proposition The business case for making the move to Building Information Modeling continues to grow. The potential for a better end-to-end design workflow is driven by the concept of a BIM as a ‘single source of truth’ in building design. Principals love the marketing power of BIM, citing the strong competitive advantage they get from it. This is especially true when firms solicit business from new clients. Business Value of BIM 2017 these reasons without our help. These benefits are outlined in the We’d like to make a proposal to you, and “Business Value of BIM 2017” report from we’ve created this document to support it. McGraw-Hill. They report that building Bricsys declares: don’t fight the BIM wave owners also see the long-term value - transition to riding it. You can dive into a of BIM - especially around reduced flexible transition workflow that supports documentation errors and less rework. -

3D Model-Based Collaboration During Design Development And

3D MODEL-BASED COLLABORATION IN DESIGN DEVELOPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION OF COMPLEX SHAPED BUILDINGS SUBMITTED: September 2007 REVISED: March 2008 PUBLISHED: June 2008 EDITORS: T. Olofsson, G. Lee & C. Eastman Kihong Ku, Assistant Professor, Myers-Lawson School of Construction, College of Architecture and Urban Studies, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA; [email protected]; www.bc.vt.edu/faculty/kku Spiro N. Pollalis, Professor of Design, Technology and Management, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA; [email protected]; www.gsd.harvard.edu/~pollalis Martin A. Fischer, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Director, Center for Integrated Facility Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; [email protected]; www.stanford.edu/~fischer Dennis R. Shelden, Ph.D., Chief Technology Officer, Gehry Technologies, Los Angeles, CA, USA; [email protected]; http://www.gehrytechnologies.com SUMMARY: The successful implementation of complex-shaped buildings within feasible time and budget limits, has brought attention to the potential of computer-aided design and manufacturing technologies (CAD/CAM), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and the need for integrated practice. At the core of an integrated practice vision lies the intimate collaboration between the design team and construction team and a digital three-dimensional model, often with parametric and intelligent characteristics. With the shift from two-dimensional (2D) paper-based representations to three- dimensional (3D) geometric representations in building information models (BIM), architects and engineers have streamlined ‘inner’ design team communication and collaboration. However, practice conventions have posed significant challenges when attempting to collaborate on the designer’s 3D model with the ‘external’ design team – involving the architect (or engineer)-of-record, and contractor, construction manager or fabricator, etc. -

Ficha-Openbim-Software-Civil-3D.Pdf

Ficha Descriptiva de funcionalidades OpenBIM Civil 3D / Autodesk Ficha Descriptiva de las funcionalidades OpenBIM disponibles con Civil 3D de Autodesk Nombre comercial: Civil 3D Versión analizada: 2020.2 Autor: Autodesk Fecha de publicación: 20/01/2020 Tabla de Contenido Descripción general del software analizado ................................................................................................. 2 Software de diseño y documentación de infraestructuras civiles .............................................................. 2 Funcionalidades de Importación de IFC ........................................................................................................ 3 Funcionalidades de Exportación de IFC ........................................................................................................ 3 Funcionalidades de Importación de COBie ................................................................................................... 3 Funcionalidades de Exportación de COBie ................................................................................................... 3 Funcionalidades de Intercambio vía BCF ...................................................................................................... 4 Recomendaciones para un correcto flujo de trabajo ................................................................................... 4 Flujo de trabajo y/o recomendaciones para una correcta exportación a IFC .......................................... 4 Flujo de trabajo y/o recomendaciones para una -

9783030335694.Pdf

Research for Development Bruno Daniotti Marco Gianinetto Stefano Della Torre Editors Digital Transformation of the Design, Construction and Management Processes of the Built Environment Research for Development Series Editors Emilio Bartezzaghi, Milan, Italy Giampio Bracchi, Milan, Italy Adalberto Del Bo, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy Ferran Sagarra Trias, Department of Urbanism and Regional Planning, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Francesco Stellacci, Supramolecular NanoMaterials and Interfaces Laboratory (SuNMiL), Institute of Materials, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Vaud, Switzerland Enrico Zio, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy; Ecole Centrale Paris, Paris, France The series Research for Development serves as a vehicle for the presentation and dissemination of complex research and multidisciplinary projects. The published work is dedicated to fostering a high degree of innovation and to the sophisticated demonstration of new techniques or methods. The aim of the Research for Development series is to promote well-balanced sustainable growth. This might take the form of measurable social and economic outcomes, in addition to environmental benefits, or improved efficiency in the use of resources; it might also involve an original mix of intervention schemes. Research for Development focuses on the following topics and disciplines: Urban regeneration and infrastructure, Info-mobility, transport, and logistics, Environment and the land, Cultural heritage and landscape, Energy, Innovation in processes and technologies, Applications of chemistry, materials, and nanotech- nologies, Material science and biotechnology solutions, Physics results and related applications and aerospace, Ongoing training and continuing education. Fondazione Politecnico di Milano collaborates as a special co-partner in this series by suggesting themes and evaluating proposals for new volumes. -

BIM for Architects ARCHICAD Is

Charles Perkins Centre, Sydney, Australia fjmt | francis-jones morehen thorp - https://fjmtstudio.com Photo © Demas Rusli ARCHICAD is BIM ARCHICAD© is the leading Building Information Modeling (BIM) software solution for the architecture and design industry. Work in 3D: All creative work and design documentation happens in 3D, so you can make design decisions and see the results in a project’s real, 3D environment. One, central model: Designers work on a single building model to create, document, and construct their ideas — changes are fast and automatic. Documentation made easy: Automatically updated, one-click documentation makes even the most tedious tasks fast and easy. Developed by architects for architects: ARCHICAD’s focus on architecture, backed by more than 30 years of experience and innovation, is evident in millions of buildings worldwide. Dedicated tools: ARCHICAD’s focus on architects ensures that the design workflows and collaboration tools serve their needs BIM for Architects from the first sketch through the full life-cycle of the building. Your platform, your choice: ARCHICAD was the first architectural ARCHICAD’s focus on architecture, design, and design software available for both the Microsoft Windows creativity, combined with cutting-edge technology and Apple Macintosh operating systems — innovations for and innovation, allows architects to do what they do the iOS and Android platforms ensure seamless design and best: design great buildings. collaboration among all project stakeholders. Intuitive BIM modeled with ARCHICAD with modeled Sagrada Familia, Barcelona Familia, Sagrada With its architect-inspired toolset, ARCHICAD feels like the most natural BIM application on the market. Smart tools: Throughout the years, ARCHICAD has advanced not only in areas such as design workflow, but also in the details — providing intuitive tools not instantly visible, but at your fingertips when you need them.