Kingsbury Works - Wings and Wheels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 8/21 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

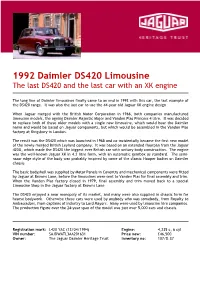

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine the Last DS420 and the Last Car with an XK Engine

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine The last DS420 and the last car with an XK engine The long line of Daimler limousines finally came to an end in 1992 with this car, the last example of the DS420 range. It was also the last car to use the 44-year old Jaguar XK engine design When Jaguar merged with the British Motor Corporation in 1966, both companies manufactured limousine models, the ageing Daimler Majestic Major and Vanden Plas Princess 4 litre. It was decided to replace both of these older models with a single new limousine, which would bear the Daimler name and would be based on Jaguar components, but which would be assembled in the Vanden Plas factory at Kingsbury in London. The result was the DS420 which was launched in 1968 and co-incidentally became the first new model of the newly-merged British Leyland company. It was based on an extended floorpan from the Jaguar 420G, which made the DS420 the biggest ever British car with unitary body construction. The engine was the well-known Jaguar XK in 4.2 litre form, with an automatic gearbox as standard. The semi- razor edge style of the body was probably inspired by some of the classic Hooper bodies on Daimler chassis The basic bodyshell was supplied by Motor Panels in Coventry and mechanical components were fitted by Jaguar at Browns Lane, before the limousines were sent to Vanden Plas for final assembly and trim. When the Vanden Plas factory closed in 1979, final assembly and trim moved back to a special Limousine Shop in the Jaguar factory at Browns Lane The DS420 enjoyed a near monopoly of its market, and many were also supplied in chassis form for hearse bodywork. -

March/April 2007

IN THIS ISSUE • Portable Auto Storage .................... 6 • Reformulated Motor Oils ................. 5 • AGM Minutes .................................... 2 • Speedometer Cable Flick ................ 6 • At the Wheel ..................................... 2 • Speedometer Drive Repair ............. 7 • Austin-Healey Meet ......................... 3 • Tulip Rallye ....................................... 3 • Autojumble ..................................... 14 • Vehicle Importation Laws ............... 7 • Body Filler Troubles ........................ 6 • What Was I Thinking? ..................... 1 • Brits ‘Round the Parks AGM ......... 13 • World Record Garage Sale ............. 8 • Easidrivin’ ........................................ 1 • Your Rootes Are Showing .............. 6 • Executive Meeting ........................... 1 May 1 Meeting • High-Tech Meets No-Tech ............... 4 7:00 - Location TBA • MGs Gather ...................................... 9 May 18-20 AGM • MG Show Car Auction ..................... 4 • OECC 2007 Roster ........................ 11 Brits ‘Round the Parks • OECC/VCB Calendar ..................... 14 See Page __ For Details! • Oil in Classic Cars ........................... 3 Jun 5 Meeting • Oil is Killing Our Cars ...................... 5 7:00 - Location TBA OLD ENGLISH CAR CLUB OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, VANCOUVER COAST BRANCH MAR-APR 2007 - VOL 12, NUM 2 Easidrivin’ What Was I Alan Miles Thinking? The Smiths Easidrive automatic transmission was first introduced by Rootes Motors Or the Restoration of a in September 1959 in the UK and February 1960 in the U.S. It was offered as an option on the Series IIIA Hillman Minx and for the next three years on subsequent Minxes and Demon Sunbeam Imp - Part VI John Chapman Unfortunately I don't have much to report on the progress of the Imp restoration. Pat Jones has spent some 20-25 hours so far welding pieces of metal into the multitude of holes in the car created by the dreaded rust bug. After all these hours welding I can report that we have all the rear sub- frame replaced. -

Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust by Linsey Siede Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust (Cont)

CLASSIC MARQUE FEBRUARY 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS OF THE XJ40 (1986-2021) THE OFFICIAL MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE JAGUAR DRIVERS CLUB OF SA Solitare Jaguar Club Torque - President’s Column NEW JAGUAR E-PACE DYNAMIC, ELECTRIFIED, CONNECTED, EVOLVED. Jaguar’s first compact SUV has undergone a dynamic evolution, with the new E-PACE delivering a more assertive, connected, and refined driving experience than ever before. A refreshed exterior, enhanced interior, the latest Pivi Pro infotainment, new vehicle architecture, and a choice of powerful and efficient engines – including an advanced Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) powertrain – making the new Jaguar E-PACE an irresistible motoring package. Solitaire Jaguar 32 Belair Road, Hawthorn SA 5062. Tel: 1300 719 429 solitairejaguar.com.au Overseas model shown. DL65541 PAGE 2 THE OFFICIAL MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE JAGUAR DRIVERS CLUB OF SA Solitare Jaguar Club Torque - President’s Column President’s Column – January 2021 will be arranging a number of special events to ensure worthy celebrations of February is traditionally the start of this milestone. a new year full of exciting events and CONTENTS (Feature Articles) meetings for JDCSA members. Yet this With the failure of SA Jag Day in 2020, year it seems the year has already got off due to COVID-19 restrictions The New Member - Don Bursil 6-7 to a fantastic start with a special January Presidents Picnic, as a substitute event Edition of Classic Marque (Our Editor has been planned and is now published New Member - Stephen Perkins 9 has done a fantastic job once again) and on TidyHQ with registrations open. -

Crankpin Bearings in High Output Aircraft Piston Engines the Evolution of Their Design and Loading by Robert J

Crankpin Bearings in High Output Aircraft Piston Engines The Evolution of their Design and Loading by Robert J. Raymond July 2015 Abstract powered truck. There you will invariably find a 6-cylinder, 4-stroke cycle, open chamber, turbocharged, aftercooled The development of the crankpin bearing in high output engine with electronically controlled fuel injection. Gone are aircraft piston engines is traced over the period 1915-1950 in the two-stroke cycle, divided combustion chambers, and the a large number of liquid and air cooled engines of both many variants of mechanical injection systems found in American and European origin. The changes in bearing truck engines of the past. dimensions are characterized as dimensionless ratios and At the end of the large piston engine era there was still a the resulting changes in the associated weights of rotating broad spectrum of engine configurations being produced and reciprocating parts as weight densities at the crankpin. and actively developed. Along with the major division Bearing materials and developments are presented to indi- between liquid and air-cooled engines there was a turbo- cate how they accommodated increasing bearing loads. compounded engine, a four-row air-cooled radial engine, Bearing loads are characterized by maximum unit bearing engines with poppet valves and engines with sleeve valves, pressure and minimum oil film thickness and plotted as a all in production. There were also a two-stroke turbo-com- function of time. Most of the data was obtained from the lit- pounded Diesel engine, a 2-stroke spark ignition sleeve erature but some results were calculated by the author. -

The Realanorak Quiz ANSWERS

The REAL Anorak Quiz ANSWERS Round 1:- Advertising Slogans No. Question Answer 1 Safety Fast MG 2 You can depend on An Austin it! 3 Hand built by robots Fiat (Strada) (as opposed to the Austin Ambassador, which was “Hand Built by Roberts” in the “Not the Nine o’Clock News”, sketch. See https://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=FU-tuY0Z7nQ ) 4 Everything we do is Ford driven by you No. Question Answer 5 Grace…. Space…. Jaguar Pace…. (It’s a shame they have forgotten the first one of these!) 6 The pioneer and still Morgan Runabout the best 7 The only car with its Wolseley name in lights (from its patented illuminated radiator badge) 8 Zoom, zoom, zoom Mazda 9 Made like a gun Royal Enfield (motorcycle) No. Question Answer 10 The power of dreams Honda 11 Takes your breath Peugeot away 12 The car in front is a Toyota 13 Sure as the sunrise Albion lorries (Should have been easy for Dire Straits fans. See “Border Riever”: https://www.youtube.com/watc h?v=Gi35yMzUuVg ) 14 Ugly is only skin Volkswagen (Beetle) deep 15 It’s a ….. honest Skoda No. Question Answer 16 The ultimate driving BMW machine 17 The silent sports car Bentley 18 As old as the Riley industry as modern as the hour 19 Vorsprung durch Audi Technik 20 The relentless Lexus pursuit of perfection Round 2:- Manufacturers’ Names No. Question Answer 1 The Latin for “I roll” Volvo (from the company’s origin as a subsidiary of SKF Bearings) 2 The founders name and an early hillclimb Aston-Martin location (Lionel Martin-Aston Clinton hillclimb) 3 Derived from the Norman, Fulk de Breant’s Vauxhall Hall, which gave its name to an area of London 4 The founder’s daughter Mercedes 5 Chemical symbol for Aluminium and the Alvis Latin for “Strong” (first made aluminium pistons) 6 A high level of achievement Standard 7 General Purpose Vehicle Jeep 8 The owner and his famous shell bearings Vanwall (Tony Vandervell/Thin wall bearings) 9 Named after a dealership in Oxford which MG sold tuned versions of cars made locally. -

OCT-JAN 12 B 15/01/2019 14:06 Page 1 FEBRUARY - MAYFEBRUARY- 2018 FEBRUARY - MAY 2019 RELEASE PROGRAMME

FEB-MAY 19 MASTER_OCT-JAN 12 B 15/01/2019 14:06 Page 1 FEBRUARY - MAY 2018 - FEBRUARY MAY FEBRUARY - MAY 2019 RELEASE PROGRAMME www.oxforddiecast.co.uk Oxford Haulage Company 1:76 Oxford Automobile Company 1:76 Oxford Emergency 1:76 Oxford Commercials 1:76 Oxford Military 1:76 Oxford Showtime 1:76 Oxford Omnibus Company 1:76 Oxford Automobile Company 1:43 Oxford Commercials 1:43 N Scale 1:148 History Of Flight 1:72 Oxford Aviation 1:72 Gift Items 1:76/1:87/1:43/1:148/1:1200 American 1:87 Special Items 1:18/1:24/1:43/1:50/1:76 43WFA001 Weymann Fanfare - South Wales Cararama 1:24/1:43/1:50 Welly 1:24/1:32 FEB-MAY 19 MASTER_OCT-JAN 12 B 15/01/2019 14:06 Page 2 1:76 76ATK004 76ATKL003 76ATKL005 DUE Q2/2019 76BD006 Atkinson Borderer Low Loader Atkinson 8 Wheel Flatbed Tennant Transport Atkinson Cattle Truck L Davies & Sons BRS Bedford OY Dropside NCB Mines Rescue 1960 - 1980 1940 - 1960 1940 - 1960 1940 - 1960 76BD012 76CONT00109 76CONT00113 76D28003 Bedford OX Queen Mary Trailer Wynns Container 09 Container 13 DAF 3300 Short Van Trailer Pollock 1940 - 1960 2010 - 2010 2010 - 2010 1970 - 1980 76DAF003 76DBU003 76DT004 76DXF002 Leyland Daf FT85CF Curtainside Eddie Stobart Scania Topline Drawbar Eddie Stobart Diamond T Ballast Pickfords DAF XF Euro 6 Curtainside Wrefords 1990 - 2010 2000 - 2010 1940 - 1970 2010 - 2020 Oxford Oxford Haulage Company 76DXF003 76DXF004 DUE Q1/2019 76EC003 76FCG004 DAF XF William Armstrong Livestock Trailer DAF XF Euro 6 Livestock Transporter Skeldons ERF EC Flatbed Trailer Pollock Ford Cargo Box Van Royal Mail 2 -

Marque & Model

Marque & Model Part No. Marque & Model Part No. AC Ferguson Ace/Aceca to 1963 (AC engine) FA001 T20 Petrol/TVO (Tecalemit 2016) FA109 ACE Bristol 6 cylinder engine FA021 135 Diesel (Tecalemit 5605) FA120 Alfa Romeo Some other applications FA137 105 series to 1974 FA002 Ford 100E to 1962 FA088 Consul/Zephyr/Zodiac to 1965 FA090 Ford 105E FA083 8 & 10 HP FA133 1900 to ’63 FA003 4&5 ton V8 1956-46 FA134 105 series – COMIT head FA113 Hillman Alvis Some other applications C7059 FA137 TD/TE/TF to 1963 FA004£39.60 Imp to 1972 FA028 TD21 FA029 Armstrong Siddeley HRG Hurricane 16/18HP & Whitley FA005 1500 (Singer engine) to 1956 FA060 Sapphire 234, 236 to 1958 FA006 Star Sapphire to 1960 FA007 Humber Pre-War 16HP FA030 Hawk SII to 1961 FA091 Snipe 1948 FA134 Aston Martin Jaguar 6 cylinder engine to 1963 FA008 XK120 eng W1001-W4382 FA077 Austin eng W4383 on FA078 16HP to 1948 FA096 XK140 eng G1001-6232 FA078 A35 to 1961 FA011 eng G6233 on FA079 A-series engine to 1967 FA011 MkV to 1951 FA033 B-series engine to 1969 (not FA012 MkVII eng A1001 – B5304 FA080 1500) eng B5305 – N2941 FA078 A90 to 1959 FA097 MkVIII/IX to 1961 FA079 A95 to 1959 FA098 XK150 to 1960 FA034 A125/A135 FA013 Mk1/2: C-Series engines to 1969 FA014 2.4 to engBH7968 A90 Atlantic FA031 3.4 to engKH7062 A110 FA032 3.8 to engLC4264 FA035 Austin Princess (Tecalemit 2011) FA108 Mk2 subsequent, 240, 340 FA036 2&5 ton trucks 1940-45 FA134 E-Type 3.8 FA037 FA137 E-Type S1 4.2 FA038 Some other applications 3H1968 Austin Healey E-Type S2 4.2 FA039 100/4 to 1956 FA015 S-Type/420G/MkX/420 to1969 -

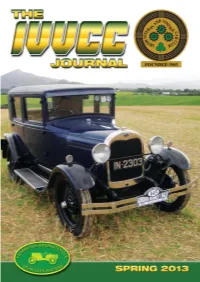

IVVCC SPRING 2013 Layout 1

HOSE. WIPE. PRE-WASH. HOSE. WIPE. WASH. HOSE. CHAMOIS. POLISH. (REPEAT) We know how much your car means to you. Which is why all classic car insurance policies through Carole Nash come with: • Irish & European Breakdown Recovery • Home Start Recovery • Free Agreed Value* • Up to €100,000 Legal Protection • 10% discount for recognised club membership* 1800 930 801 carolenash.ie Opening hours in the Ireland: Mon-Fri 9am-5.30pm, Sat 9am-1pm. *Subject to satisfying underwriting conditions. Dear Fellow Motoring Enthusiasts, elcome to the belated Spring edition of the IVVCC Journal. My sincere Wapologies for its late production, the last number of months has been hectic and left me little spare time to devote to my hobbies so to speak. I intend to produce the Summer issue quite soon. The cover photo for this edition sees the late Bill Pegum’s beloved Model ‘A’ Ford. This car belonged to his mother from new and the family name for it was ‘Bluebird’. Bill left this car and his home to the IVVCC in his will. He was a true enthusiast who actively encouraged others to get involved and indeed sourced old motors whilst on his travels around the country passing on their locations to eager enthusiasts. FRONT COVER: Bill’s car must be unique in that it belonged to one family from new. It was a The late Bill Pegum’s 1929 Ford Model ‘A’ regular attender at events in the past and we hope it will be again. (Bluebird) enjoying a day out. Our members travel worldwide in their motors and Jim, Bernie and Cian Photo by Tom Farrell O’Sullivan are a go anywhere family. -

Eligible Cars

Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique Side 1 af 3 Eligible Cars Models which took part in a Monte-Carlo Rally between 1955 and 1977 (non exhaustive list) z ABARTH : 750 - 1000 - 850TC - 1000TC z A.C. : Ace - Aceca - Bristol z ALFA-ROMEO : 1900, TI, Super, coupéSS, SZ - Giulietta, TI, Sprint, Spider, SZ - Giulia : Super, TI, TISuper, GT, GTV, GTA, GTAM - 1300GT - 1750 : GT, Spider - 2000, GTV - AlfasudTI - AlfettaGT z ALLARD : P2 z ALPINE : A106 - A108 z ALPINE-RENAULT : A110, Bulgaralpine - A310 z ALVIS : 3L. z ARMSTRONG-SIDDELEY : Sapphire z ASTON-MARTIN : DB2 - DB2/4 - DBMkIII - DB4 z AUDI : 70 - Super90 - 100S - 80, S, GT z AUSTIN : A30 - A50 - A90 - A35 - A95 - A105 - A99 - A110 - Taxi (->61) - A40 - 1100Mk1 - Authi - 1800, S - Maxi - Mini, Cooper, CooperS, 1275GT (->73) z AUSTIN-HEALEY : Sprite, Sebring - 100/6 - 3000 z AUTOBIANCHI : Primula - A112, Abarth z AUTO-UNION / DKW : 900/3=6 - 1000, S, coupé - Junior - F12 z BERKELEY : B90 z BMW : 501 - 502 - 503 - 700, S - 1500 - 1800, TI - 2000, TI - 1600, TI, 2 - 2002, TI, TII, Turbo - 2500 - 2800, CS z BOND : Equipe z BORGWARD : Isabella, TS z BRISSONNEAU-LOTZ : 4CV z BRISTOL : 403 - 405 z CHEVROLET : Impala (->66) - Camaro (->73) z CITROEN : 11B - 15/6 - ID, DS19 - 2CV (->59) - Ami6 - DS21, 23 - SM - GS - Dyane6 z DAF : Daffodil - 44 - 55 - 66 z DAIMLER : Conquest - Century - Consort z DATSUN / NISSAN : Bluebird1300, 1600, SSS - 2000 - Sunny - 240Z - Cherry - Violet z DB PANHARD : CoachHBR5 z DENZEL : 1300 z DE TOMASO : Pantera z FACEL VEGA : Facellia z FAIRTHORPE : Electron z FERRARI : 250GTBoano -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 8 March 2013 A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Plant’s first car was a Bullnose Morris Oxford, produced on 28 March 1913 Total car production to date stands at 11,655,000 and counting Over 2,250,000 new MINIs built so far, plus 600,000 classic Minis manufactured at Plant Oxford Scores of models under 14 car brands have been produced at the plant Grew to 28,000 employees in the 1960s As well as cars, produced iron lungs, Tiger Moth aircraft, parachutes, gliders and jerry cans, besides completing 80,000 repairs on Spitfires and Hurricanes Principle part of BMW Group £750m investment for the next generation MINI will be spent on new facilities at Oxford The MINI Plant will lead the celebrations of a centenary of car-making in Oxford, on 28 March 2013 – 100 years to the day when the first “Bullnose” Morris Oxford was built by William Morris, a few hundred metres from where the modern plant stands today. Twenty cars were built each week at the start, but the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day, and has contributed over 2.25 million MINIs to the total tally. Major investment is currently under way at the plant to create new facilities for the next generation MINI. BMW Group Company Postal Address BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date Subject A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Page 2 Over the decades that followed the emergence of the Bullnose Morris Oxford in 1913, came cars from a wide range of famous British brands – and one Japanese - including MG, Wolseley, Riley, Austin, Austin Healey, Mini, Vanden Plas, Princess, Triumph, Rover, Sterling and Honda, besides founding marque Morris - and MINI. -

June–July 2016 June–July 2016 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE

June–July 2016 June–July 2016 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE President: David Patten 156–160 New York Street, Martinborough 5711 Ph: 06 306 9006 Email: [email protected] Vice President: Martin Walker 460 Blockhouse Bay Road Ph: 09 626 4868 [email protected] Secretary: Mike King 21 Millar St, Palmerston North 4410 Ph: 06 357 1237 Fax: 06 356 8480 Email: [email protected] Treasurer: Peter Mackie P.O. Box 8446, Havelock North 4157 Ph: 06 877 4766 Email: [email protected] Club Captain: Winston Wingfield 7 Pioneer Crescent, Helensburgh, Dunedin 9010 Ph: 03 476 2323 Email: [email protected] Patron: Pauline Goodliffe Editor: Mike King Printer: Aorangi Print (Penny May) 125 Campbell Rd, RD 5, Feilding 4775 Ph: 06 323 4698 (home) Mob: 021-255-1140 Email: [email protected] Website: www.daimlerclub.org.nz All membership enquiries to the Secretary. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE MAGAZINE Please send all contributions for inclusion in the magazine directly to the Secretary via fax email or mail by the TENTH day of the month prior to publication. DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are purely those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Daimler and Lanchester Owners’ Club. June~July 2016 CONTENTS Page From the Driver’s Seat – National President’s Report ............................................ 2 Getting Up to Speed – National Secretary’s Report ............................................... 3 From the Patron’s Pen ............................................................................................