Juridification of the Football Field: Strategies for Giving Law the Elbow Simon Gardiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esf-2018-Brochure-300717.Pdf

IAN WRIGHT THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL THE GREATEST WEEKEND IN YOUTH FOOTBALL CONTENTS ABOUT ESF 4 ESF 2018 CALENDAR 7 CELEBRITY PRESENTATIONS 8 ESF GRAND FINALE 10 GIRLS FOOTBALL AT ESF 12 BUTLIN’S BOGNOR REGIS 14 BUTLIN’S MINEHEAD 16 BUTLIN’S SKEGNESS 18 HAVEN AYR 20 2017 ROLL OF HONOUR 22 TESTIMONIALS 24 FESTIVAL INFO, T&C’s 26 TEAM REGISTRATION FORM 29 AYR 6 - 9 April 4 - 7 May SKEGNESS ESF FINALE 20 - 23 April 7 - 8 July 4 - 7 May MINEHEAD 27 - 30 April BOGNOR REGIS 4 - 7 May 18 - 21 May Search ESF Festival of Football T 01664 566360 E [email protected] W www.footballfestivals.co.uk 3 THE ULTIMATE TOUR WAYNE BRIDGE, CASEY STONEY & SUE SMITH THE UK’S BIGGEST YOUTH FOOTBALL FESTIVAL With 1200 teams and 40,000 people participating, ESF is the biggest youth football festival in the UK. There’s nowhere better to take your team on tour! THE ULTIMATE TOUR TOUR ESF is staged exclusively at Butlin’s award winning Resorts in Bognor Regis, Minehead and Skegness, and Haven’s Holiday Park in Ayr, Scotland. Whatever the result on the pitch, your team are sure to have a fantastic time away together on tour. CELEBRITY ROBERT PIRES PRESENTATIONS Our spectacular presentations are always a tour highlight. Celebrity guests have included Robert Pires, Kevin Keegan, Wayne Bridge, Stuart Pearce, Casey Stoney, Sue Smith, Robbie Fowler, Ian Wright, Danny Murphy and more. ESF GRAND FINALE AT ST GEORGE’S PARK Win your age section at ESF 2018 and your team will qualify for the prestigious ESF Grand Finale, our Champion of Champions event. -

Disability News Newsletter for Newcastle United’S Disabled Supporters Around the World September 2018 Newsletter

SEPTEMBER 2018 NEWSLETTER NEWCASTLE UNITED DISABILITY NEWS NEWSLETTER FOR NEWCASTLE UNITED’S DISABLED SUPPORTERS AROUND THE WORLD SEPTEMBER 2018 NEWSLETTER NEWCASTLE UNITED 1. INTRODUCTION 2. NUFC AND STEPHEN 3. FOUNDATION NEWS 4. BOX OFFICE NEWS 5. SENSORY ROOM UPDATE 1. INTRODUCTION The new season is upon us and although we have faced the expected difficult start, we're all behind the team and believe in them wholeheartedly. The sensory room is now fully up and running, and is proving very popular. The wheelchair spaces have been increased, so we now have 234 slots available. There is more accessible seating in the Gallowgate. Change is always ongoing. I was at a meeting with the disabled supporters association (NUDSA) and they are this month celebrating 20 years in business. They are a quite remarkable group of individuals, who never fail to inspire me. The main protagonists are Gareth Beard, who you may remember had an article in last month’s newsletter and has been the Chair of NUDSA for years, Stephen Miller who is a highly decorated Paralympian, and writes in this newsletter, Ros Miller (Stephens mum / coach / boss) and the Leazes ender Joe Ayton who has been there since the start. They have produced a magnificent magazine which celebrates their 20 years and looks back at the journey. It is well worth a read if you can get a copy. NUDSA have been instrumental in working with NUFC to invoke a better deal for disabled supporters, and I hope they are even stronger in 2028 when they celebrate their 30th. Dave Balmer Lead Safeguarding, Welfare & Equality Officer 1 SEPTEMBER 2018 NEWSLETTER NEWCASTLE UNITED 2. -

Hillsborough Esquire Feature.Pdf

inquire | section name feature | hillsborough Everything had gone to plan up until of a club that won League titles and ran out for the match did not seem to that point. We had got to Sheffield on the European Cups as a matter of course, a be coming from our section behind train, been put on a bus at the station club that attracted out-of-towners like us the goal. At 10 to three, it was hot enough and were now standing outside a paper with its quiet, consistent brilliance and to feel lightheaded, and my view of the shop near the Leppings Lane entrance large, ebullient following, Kenny Dalglish’s pitch had narrowed to a slit between of Hillsborough, home of Sheffield side was something special. the hair, the skin and the hats in front of Wednesday FC. Phil lit a cigarette. It was The West Stand at the Leppings Lane me. The sounds now concerning me were a clear spring day, warm enough for me to end was the smaller of the two ends at not those coming from the other three question the wisdom of wearing my beige, Hillsborough, with a shallow bank of sides of the ground, but the breathing zip-up bomber jacket. terracing split into pens located below a and groaning and rising voices in my We shouldn’t have been there, really; single tier of covered seats. To our left was immediate vicinity — and the banging a pair of 18-year-old middle class boys the North Stand, also slowly filling with of my heartbeat in my ears. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

RANGERS FC RANGERS FC in the in the 1980S

in the The Players’ Stories The Players’ 1980s ALISTAIR AIRD ALISTAIR RANGERS FC ALISTAIR AIRD RANGERS FC in the 1980s Contents Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 11 Safe Hands: The Goalkeepers Jim Stewart (1981–1984) 21 Nicky Walker (1983–1989) 31 Case For The Defence: The Defenders Hugh Burns (1980–1987) 47 Ally Dawson (1975–1987) 62 Jimmy Nicholl (1983–1984, 1986–1989) 73 Stuart Munro (1984–1991) 87 Dave MacKinnon (1982–1986) 100 Stuart Beattie (1985–1986) 112 Colin Miller (1985–1986) 123 Richard Gough (1987–1998) 134 Dave McPherson (1977–1987, 1992–1994) 151 The Engine Room: The Midfielders Bobby Russell (1977–1987) 169 Derek Ferguson (1982–1990) 178 Ian Durrant (1982 -1998) 196 Ian Ferguson (1988–2000) 216 David Kirkwood (1987–1989) 237 Up Front: The Forwards John MacDonald (1978–1986) 249 Gordon Dalziel (1978–1984) 261 Derek Johnstone (1970–1983, 1985-1986) 271 Iain Ferguson (1984–1986) 286 Mark Walters (1987–1991) 296 Statistics 306 Index 319 SAFE HANDS THE GOALKEEPERS 19 Just Jim Jim Stewart (1981–1984) James Garvin Stewart’s football career was stuck in a rut in March 1981 Aged 27 he was languishing in the Middlesbrough reserve team, his two caps for Scotland in 1977 and 1979 a seemingly distant memory Enter John Greig The Rangers manager was looking for a goalkeeper to provide competition for the timeless Peter McCloy and he looked to Teesside to find one ‘I got a phone call from Davie Provan, who was on the coaching staff at Ibrox at the time, to ask me if I’d be interested in signing for Rangers,’ said Stewart ‘There was no question -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

Potential Liability for Sports Injuries

PROTECT YOUR BLIND SIDE: POTENTIAL LIABILITY FOR SPORTS INJURIES Presented and Prepared by: Matthew S. Hefflefinger [email protected] Peoria, Illinois • 309.676.0400 Prepared with the Assistance of: Timothy D. Gronewold [email protected] Peoria, Illinois • 309.676.0400 Heyl, Royster, Voelker & Allen PEORIA • SPRINGFIELD • URBANA • ROCKFORD • EDWARDSVILLE © 2010 Heyl, Royster, Voelker & Allen 15528755_5.DOCX C-1 PROTECT YOUR BLIND SIDE: POTENTIAL LIABILITY FOR SPORTS INJURIES I. INJURIES TO PARTICIPANTS ................................................................................................................... C-3 A. Contact Sports Exception .......................................................................................................... C-3 B. Assumption of Risk ...................................................................................................................... C-5 1. Exculpatory Clauses / Agreements ......................................................................... C-5 2. Implied Assumption of Risk ...................................................................................... C-8 II. INJURIES TO SPECTATORS ...................................................................................................................... C-9 A. Hockey Facility Liability Act (745 ILCS 52/1 et seq.) ........................................................ C-9 B. Baseball Facility Liability Act (745 ILCS 38/1 et seq.) ..................................................... C-10 III. PROTECTION -

5 Sport and EU Competition Law

5 Sport and EU competition law In applying EU competition law to sport, the Directorate General for Competition Policy (herein referred to as the Commission) has been caught between three powerful forces. First, the Commission has a constitutional commitment to promote and protect the free market principles on which much of the Treaty of Rome is based. In this capacity it shares a close rela- tionship with the ECJ. The ECJ’s rulings in Walrave, Donà and Bosman have played an important role in placing sport on the EU’s systemic agenda in a regulatory form. The Commission has a constitutional obligation to follow the ECJ’s line of reasoning on sport, given its role in enforcing ECJ rulings. As such, sport has passed on to the EU’s institutional agenda through the regulatory venue, the prevailing definition stressing sports commercial sig- nificance over and above its social, cultural and educational dimensions. The second major influence on Commission jurisprudence in the sports sector is administrative. Although primary and secondary legislation has equipped the Commission with the necessary legal powers to execute this commitment, it lacks the necessary administrative means to carry out formal investigations into abuses in all sectors of the economy. In the face of a large and growing caseload, the Commission has had to adopt creative means in order to turn over cases. In particular, the Commission has resorted to the use of informal procedures to settle cases rather than adopting formal deci- sions. For some time it has been felt by Commission officials that the proce- dures for applying competition law are in need of reform. -

Turnham Classes

Nursery Class – Floella Benjamin Floella Benjamin was born in Trinidad in 1949 and came to England in 1960. She is an actress, presenter, writer, producer, working peer and an active advocate for the welfare and education of children. She is best known as a presenter of the iconic BBC children's television programmes Play School and Play Away, and she continues to make children's programmes. Her broadcasting work has been recognized with a Special Lifetime Achievement BAFTA and OBE. She was appointed a Baroness in the House of Lords as Baroness Benjamin of Beckenham in 2010. In 2012 she was presented with the prestigious J. M. Barrie Award by Action for Children's Arts, for her lasting contribution to children's lives through her art. Floella has written thirty books, including Coming to England, which is used as a resource in schools in social and cross-curricular areas. The book was adapted into an award- winning film for BBC Education Trish Cooke – Reception Trish Cooke is a British playwright, actress, television presenter and award-winning children’s author. She was born in Bradford, Yorkshire. Her parents are from Dominica in the West Indies. She comes from a large family, with six sisters, three brothers, eight nephews, six nieces, three great-nieces and one great-nephew, all of whom provide her with the inspiration for her picture books. One of her most successful books is called ‘So Much’, which is a joyful celebration of family life. She is known by many from her days presenting the preschool BBC programme Playdays. -

Advanced Information

Title information Stoke City Minute By Minute Covering More Than 500 Goals, Penalties, Red Cards and Other Intriguing Facts By Simon Lowe Key features • Fascinating look back at Stoke City’s most important moments and greatest goals – with the times, dates and descriptions of how they hit the net • First book of its kind on the Potters, with hundreds of memorable moments revisited • A treasure trove of nostalgia for Stoke City fans, charting the club's proud history with all the drama, elation, heartache, highs and lows • Revisits the goals scored by club legends of various eras – including Freddie Steele, Jimmy Greenhoff, John Ritchie, Mark Chamberlain, Mark Stein, Mike Sheron, Peter Thorne, Ricardo Fuller, Jon Walters and Peter Crouch • Publicity campaign planned including radio, newspapers, websites, podcasts and magazines Description Stoke City: Minute by Minute takes you on a tumultuous journey through the Potters’ remarkable history. Relive all the breathtaking goals, heroic penalty saves, Wembley wins, game-changing incidents, sending offs and other memorable moments in this unique by-the-clock guide. From the glory days of Stanley Matthews, the celebrated Tony Waddington era, Lou Macari’s beloved team, Tony Pulis’s promotion to the Premier League and Mark Hughes’s ‘Stokealona’ side, this book covers everything. Featuring goals from Freddie Steele, Jimmy Greenhoff, John Ritchie, Mark Chamberlain, Mark Stein, Mike Sheron, Peter Thorne, Ricardo Fuller and Peter Crouch, plus countless others – the book is crammed with thrilling memories from kick-off through to the final whistle. Revisit the Potters’ most spectacular modern feats and learn things you didn't know about the club’s incredible past – from goals scored in the opening seconds to those last-gasp, extra-time winners that have thrilled generations of fans at the Victoria Ground and Bet365 Stadium. -

Estimated Costs of Contact in Men's Collegiate Sports

ESTIMATED COSTS OF CONTACT IN MEN’S COLLEGIATE SPORTS By Ray Fair and Christopher Champa August 2017 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2101 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ Estimated Costs of Contact in Men’s Collegiate Sports Ray C. Fair∗ and Christopher Champayz August 2017 Abstract Injury rates in twelve U.S. men’s collegiate sports are examined in this paper. The twelve sports ranked by overall injury rate are wrestling, football, ice hockey, soccer, basketball, lacrosse, tennis, baseball, indoor track, cross country, outdoor track, and swimming. The first six sports will be called “contact” sports, and the next five will be called “non-contact.” Swimming is treated separately because it has many fewer injuries. Injury rates in the contact sports are considerably higher than they are in the non-contact sports and they are on average more severe. Estimates are presented of the injury savings that would result if the contact sports were changed to have injury rates similar to the rates in the non-contact sports. The estimated savings are 49,600 fewer injuries per year and 5,990 fewer injury years per year. The estimated dollar value of these savings is between about 0.5 and 1.5 billion per year. About half of this is from football. Section 7 speculates on how the contact sports might be changed to have their injury rates be similar to those in the non-contact sports. ∗Cowles Foundation, Department of Economics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8281. -

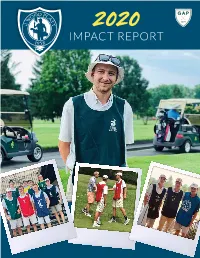

Impact Report J

2020 IMPACT REPORT J. WOOD PLATT CADDIE SCHOLARSHIP TRUST 145 Platt-Scholars hail from 41 GAP Member Clubs Scholars attend 58 colleges and universities. ONE CADDIE, ONE GOLFER, (Scholars are free to choose the school that they attend and must ONE FUTURE AT A TIME. maintain grade point average and caddying minimums for the entire term of their scholarship.) The J. Wood Platt Caddie Scholarship Trust is the official charitable arm of GAP. The Trust’s mission, More than which has remained constant since its inception, $ is to financially aid deserving caddies in their pursuit 1 .2 million of higher education. Since 1958, more than $23 million in Scholarships with an has been awarded to more than 3,500 caddies. $ 8,200 The Outstanding Network of JWP Donors Average Award features partners in our work who: in 2020–21 REWARD determination and perseverance. 42 Scholars successfully completed their INVEST in our future leaders. degrees and joined the JWP Alumni Community. STRENGTHEN the crucial caddie legacy. 2 | 2020 Impact Report www.PlattCaddieScholarship.org | 3 Shown, left to right J. Lloyd Adkins North Hills Country Club • Pennsylvania State University MEET THE NEW CLASS Thomas Andruszko Rolling Green Golf Club • Neumann University Thomas Bagnell IV Philadelphia Cricket Club • Pennsylvania State University James Blaisse Rolling Green Golf Club • DeSales University 2020-2021 Hunter Bradbury Green Valley Country Club • Providence College Donovan Brickus Stonewall • University of Pittsburgh Dylan Cardea Tavistock Country Club • Rutgers University