PADI's Guide to Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supervised Dive

EFFECTIVE 1 March 2009 MINIMUM COURSE CONTENT FOR Supervised Diver Certifi cation As Approved By ©2009, Recreational Scuba Training Council, Inc. (RSTC) Recreational Scuba Training Council, Inc. RSTC Coordinator P.O. Box 11083 Jacksonville, FL 32239 USA Recreational Scuba Training Council (RSTC) Minimum Course Content for Supervised Diver Certifi cation 1. Scope and Purpose This standard provides minimum course content requirements for instruction leading to super- vised diver certifi cation in recreational diving with scuba (self-contained underwater breathing appa- ratus). The intent of the standard is to prepare a non diver to the point that he can enjoy scuba diving in open water under controlled conditions—that is, under the supervision of a diving professional (instructor or certifi ed assistant – see defi nitions) and to a limited depth. These requirements do not defi ne full, autonomous certifi cation and should not be confused with Open Water Scuba Certifi cation. (See Recreational Scuba Training Council Minimum Course Content for Open Water Scuba Certifi ca- tion.) The Supervised Diver Certifi cation Standards are a subset of the Open Water Scuba Certifi cation standards. Moreover, as part of the supervised diver course content, supervised divers are informed of the limitations of the certifi cation and urged to continue their training to obtain open water diver certifi - cation. Within the scope of supervised diver training, the requirements of this standard are meant to be com- prehensive, but general in nature. That is, the standard presents all the subject areas essential for su- pervised diver certifi cation, but it does not give a detailed listing of the skills and information encom- passed by each area. -

2020 Instructor Manual

INSTRUCTOR MANUAL Product No. 79173 (Rev. 12/19) Version 2020 © PADI 2020 PADI INSTRUCTOR MANUAL PADI® Instructor Manual © PADI 2020 No part of this product may be reproduced, sold or distributed in any form without the written permission of the publisher. ® indicates a trademark is registered in the U.S. and certain other countries. Published by PADI 30151 Tomas Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688-2125 USA Printed in USA Product No. 79173 (Rev. 12/19) Version 2020 Scuba diving can never be entirely risk-free. However, by adhering to the standards within this manual whenever training or supervising divers who participate in PADI courses and programs, PADI Members can provide a strong platform from which divers and novices can learn to manage those risks and have fun in the process. How to Use This Manual This manual provides PADI course requirements. Text appearing in boldface print denotes required standards that may not be deviated from while teaching the course. PADI Standards do not, however, supersede local laws or regulations. Keep informed of these wherever you teach. Though all PADI Members use this manual, it is written from the instructor’s perspective, except for course performance requirements. These are written from the student diver’s or program participant’s perspective, stating specifcally what must be demonstrated or performed. As a starting point, become familiar with the items in the Commitment to Excellence section. This includes the PADI Professional’s Creed, PADI Member Code of Practice and Youth Leader’s Commitment. This section outlines your professional commitment to diver safety, responsibility and risk management. -

SDI Diver Standards

part2 SDI Diversdi Standards diver standards SDI Standards and Procedures Part 2: SDI Diver Standards 2 Version 0221 SDI Standards and Procedures Part 2: SDI Diver Standards Contents 1. Course Overview Matrix ..............................11 2. General Course Standards .......................... 13 2.1 Administrative ........................................................................13 2.2 Accidents .................................................................................14 2.3 Definitions ..............................................................................14 2.4 Confined Water Training ......................................................15 2.5 Open Water Training ............................................................15 2.6 Student – Minimum Equipment Requirements ..............16 2.7 Instructor – Minimum Equipment Requirements ..........16 2.8 Temporary Certification Cards ...........................................17 2.9 Upgrading from SDI Junior certification to full SDI certification ...................................................................................17 3. Snorkeling Course ....................................... 18 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................18 3.2 Qualifications of Graduates.................................................18 3.3 Who May Teach ......................................................................18 3.4 Student to Instructor Ratio ..................................................18 3.5 Student -

Dive Courses Price List

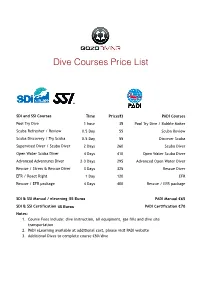

Dive Courses Price List ! ! SDI and SSI Courses Time Price(€) PADI Courses Pool Try Dive 1 hour 35 Pool Try Dive / Bubble Maker Scuba Refresher / Review 0.5 Day 55 Scuba Review Scuba Discovery / Try Scuba 0.5 Day 55 Discover Scuba Supervised Diver / Scuba Diver 2 Days 260 Scuba Diver Open Water Scuba Diver 4 Days 410 Open Water Scuba Diver Advanced Adventures Diver 2-3 Days 295 Advanced Open Water Diver Rescue / Stress & Rescue Diver 3 Days 325 Rescue Diver EFR / React Right 1 Day 120 EFR Rescue / EFR package 4 Days 400 Rescue / EFR package SDI & SSI Manual / elearning €5545 Euros PADI Manual €65 SDI & SSI Certification €4535 Euros PADI Certification €70 Notes: 1. Course Fees include: dive instruction, all equipment, gas fills and dive site transportation 2. PADI eLearning available at additional cost, please visit PADI website 3. Additional Dives to complete course €50/dive ! ! SDI and SSI Specialty Courses Time Price(€) PADI Specialty Courses Sidemount 4 Days 500 Sidemount Computer Nitrox (incl.2 dives) 1 Day 150 Nitrox (incl.2 dives) Deep 2 Days 200 Deep Wreck 3 Days 200 Wreck SDI & SSI Manual / elearning €45 PADI Manual €45 SDI & SSI Certification €35 PADI Certification €70 Notes: 1. Course Fees include: dive instruction, cylinders, weights, gas fills and dive site transportation 2. Equipment rental is at additional cost 3. PADI eLearning available at additional cost, please visit PADI website 4. Other specialties are available on request 5. Additional Dives to complete course - €50/dive ! ! Professional Courses Time Price (€) Professional Courses Divemaster 2 weeks 900 Divemaster Open Water Instructor 8 Days 1,500 n/a Notes: 1. -

Noaa Diving Program Unit Diving

NOAA DIVING PROGRAM UNIT DIVING SUPERVISOR Operational Guidelines Revised 22 September 2015 Andrew W. David, Fisheries LODO A Message from the NOAA Diving Control and Safety Board The Unit Diving Supervisor is the most important position in the NOAA Diving Program. You are the final arbiter for all diving related activities at your unit: when dives occur, how the dives are executed, and who goes in the water. You are also the conduit between the NOAA Diving Control and Safety Board and your divers, explaining policies and procedures down the chain and elevating concerns and needs up the chain. Many things will be required of you as UDS. Some are tangible; others are intangible. The tangible items are listed in the following pages – which reports you need to complete, the forms required for a range of situations, etc. However the intangible requirements are far more important and impossible to define in a manual. These skills are acquired over time, and require diligence, constant attention, and the avoidance of complacency. Your decision making skills define your performance as a UDS. People’s lives depend on the decisions you make. The toughest part of the job will be to maintain safety as your highest priority and not let friendships or pressure from project leaders or supervisors exert undue influence. You are not alone in this position, your LODO/SODO and the Safety Board will back you up on tough calls. Use these resources often. The remainder of this manual is devoted to the tangible items you will use to administer the UDS duties. -

General Training Standards, Policies, and Procedures

General Training Standards, Policies, and Procedures Version 9.2 GUE General Training Standards, Policies, and Procedures © 2021 Global Underwater Explorers This document is the property of Global Underwater Explorers. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use or reproduction in any form is prohibited. The information in this document is distributed on an “As Is” basis without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in its preparation, neither the author(s) nor Global Underwater Explorers have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused, directly or indirectly, by this document’s contents. To report violations, comments, or feedback, contact [email protected]. 2 GUE General Training Standards, Policies, and Procedures Version 9.2 Contents 1. Purpose of GUE .............................................................................................................................................6 1.1 GUE Objectives ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1.1 Promote Quality Education .................................................................................................................. 6 1.1.2 Promote Global Conservation Initiatives .......................................................................................... 6 1.1.3 Promote Global Exploration Initiatives ............................................................................................. 6 -

Diving Safe Practices Manual

Diving Safe Practices Manual Underwater Inspection Program U.S. Department of the Interior February 2021 Mission Statements The Department of the Interior conserves and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, provides scientific and other information about natural resources and natural hazards to address societal challenges and create opportunities for the American people, and honors the Nation’s trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated island communities to help them prosper. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Diving Safe Practices Manual Underwater Inspection Program Prepared by R. L. Harris (September 2006) Regional Dive Team Leader and Chair Reclamation Diving Safety Advisory Board Revised by Reclamation Diving Safety Advisory Board (February 2021) Diving Safe Practices Manual Contents Page Contents .................................................................................................................................. iii 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Use of this Manual ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Diving Safety ..................................................................................................... -

Lista Mensal De Outubro 2012

Publicação oficial do IPQ, enquanto Organismo Nacional de Normalização lista mensal °°° OUTUBRO 2012 A presente -publicação tem por objetivo: - A divulgação das Normas Portuguesas recentemente editadas e anuladas, bem como das Normas Europeias adotadas como Normas Portuguesas, e das Normas Europeias e Internacionais publicadas e já disponíveis. - A divulgação pública dos projetos de Normas Portuguesas, Europeias e Internacionais, com vista à obtenção durante o período de inquérito público dos pontos de vista e contribuições nacionais que possam ser considerados na sequente elaboração, aprovação e homologação das Normas. - A divulgação de propostas de novos trabalhos de normalização europeia e internacional, para que se possa obter, durante o período de inquérito público, os pontos de vista e as contribuições nacionais. - A divulgação da edição e anulação de outros documentos normativos. ÍNDICE 1. Normas Portuguesas 1.1 Normas Portuguesas publicadas …………………………………………………………………………. 3 1.2 Normas Portuguesas anuladas …………………………………………………………………………… 4 1.3 Normas Portuguesas em re-exame ……………………………………………………………………… 8 1.4 Normas Europeias adotadas ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 2. Normas Europeias Publicadas 2.1 CEN …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 18 2.2 CENELEC ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 21 2.3 CEN/CENELEC ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 2.4 ETSI ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 23 3. Normas Internacionais publicadas IEC …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 40 ISO ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. -

Standards and Procedures

TM Standards and Procedures Version 3.2a January 2013 UTD International, LLC 11211 Sorrento Valley Road, Suite i San Diego, CA 92121 [email protected] www.unifiedteamdiving.com +1 760-585-9676 © 2013 UTD International, LLC UTD International, LLC • Standards and Procedures v3.1 Table of Contents 1.0 General ....................................................................................................1 1.1 Overview .................................................................................................1 Mission ...............................................................................................1 Ethos ..................................................................................................1 UTD Covenants .................................................................................2 Certification Philosophy .....................................................................2 Teaching Philosophies .......................................................................3 1.2 Core Teaching Principles .........................................................................3 Training Steps ....................................................................................4 1.3 Training Process and Definitions .............................................................5 Definitions Relevant to Standards and Procedures ...........................6 Evaluation ..........................................................................................7 UTD Diver Certification ......................................................................7 -

6. Supervised Diver

SDI Standards and Procedures Part 2: SDI Diver Standards 6. Supervised Diver 6.1 Introduction This course is designed to give students the necessary skills to conduct open water dives in conditions similar to their training under the direct supervision of a qualified and active dive professional. 6.2 Qualifications of Graduates Upon successful completion of this course, graduates may: 1. Participate in dives under the direct supervision of a qualified and active dive professional to depths of 12 metres / 40 feet that do not require decompression, in conditions similar to their training for up to 12 months. Appropriate surface support must be available. 2. Dive in groups of no more than four Supervised Divers per instructor 3. Enroll in the SDI Open Water Scuba Diver course. If the diver enrolls in the Open Water Scuba Diver Course before their certification expires, they may follow the Supervised Diver Upgrade Procedure.* *See Supervised Diver Upgrade procedure #6.12 for certification requirements. 6.3 Who May Teach 1. An active SDI Open Water Scuba Diver Instructor 6.4 Student to Instructor Ratio Academic 1. Unlimited, so long as adequate facility, supplies and time are provided to ensure comprehensive and complete training of subject matter. Confined Water (swimming pool-like conditions) 1. A maximum of 8 students per instructor 2. Instructors have the option of adding 2 more students with the assistance of an active assistant instructor or divemaster 3. The total number of students an instructor may have in the water is 12 with the assistance of 2 active assistant instructors or divemasters Version 0221 29 SDI Standards and Procedures Part 2: SDI Diver Standards Open Water (ocean, lake, quarry, spring, river or estuary) 1. -

2.1.2 Recreational Supervised Diver

2.1.2 Recreational Supervised Diver 2.1.2.1 Course Outcomes GUE’s Recreational Supervised Diver course is designed to provide students with sufficient knowledge, skill, and experience to dive in open water environments under the direct supervision of a dive professional. Upon fulfilling all minimum training requirements, the Recreational Supervised Diver will be qualified to: a. Dive with a professional from a recognized training agency in a diver-to-dive professional ratio not exceeding 3:1. b. Dive to a maximum depth of 40 ft/12 m. c. Dive within minimum decompression limits (MDLs), i.e., no required stops. d. Dive with appropriate surface support (e.g., access to EMS, infrastructure allowing for support in case of emergency). e. Dive in conditions equal to or better than those in which they were trained. f. Use nitrox 32 under direct supervision of a dive professional from a recognized training agency who is certified to use nitrox 32. 2.1.2.2 Prerequisites Applicants for a Recreational Supervised Diver course must: a. Submit a completed Course Registration Form, Medical History Form, and Liability Release Form to GUE HQ. b. Be included in an insurance program that specifically covers diving emergencies. c. Be physically and mentally fit. d. Be a nonsmoker. e. Obtain a physician’s prior written authorization for use of prescription drugs, except for birth control, or for any medical condition that may pose a risk while diving. f. Be a minimum of 14 years of age. Documented parental or legal guardian consent must be submitted to GUE HQ when the participant is a minor. -

US Environmental Protection Agency Dive Safety Manual

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY DIVING SAFETY MANUAL (Revision 1.3) Office of Administration and Resources Management Safety and Sustainability Division Washington, D.C. April 15, 2016 Acknowledgments The Safety and Sustainability Division (S&S) acknowledges the cooperative participation of members of EPA’s Diving Safety Board over the years, including those members listed below. Jed Campbell Gary Collins Brandi Todd Tara Houda TChris MochonCollura Steven J. Donohue Eric P. Nelson Eric Newman Mel Parsons Dave Gibson Rob Pedersen Alan Humphrey Kennard Potts William Luthans Sean Sheldrake Disclaimer This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this document. The contents of this manual reflect the views of EPA’s Diving Safety Board in presenting the standards of their operations. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency DIVING SAFETY MANUAL (Revision 1.3, April 15, 2016) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 DIVE PROGRAM POLICY .............................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Purpose .............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................