PROCEEDINGS the 92Nd Annual Meeting 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEM Newsletter Ethnomusicology Volume 51, Number 3 Summer 2017

the society for SEM Newsletter ethnomusicology Volume 51, Number 3 Summer 2017 Music, Social Justice, and Resistance Jeffrey A. Summit, Research Professor, Tufts University Department of Music n 5-7 May 2017, a group of colleagues held a confer- this conference as a way to launch projects that would Oence entitled Music, Social Justice, and Resistance engage additional colleagues and work with established in Tiverton, RI. The conference, organized by Jeffrey A. initiatives and interest groups committed to the role of Summit (Tufts University) and sponsored by The Depart- music in social justice and advocacy. Funding and space ment of Music, Tufts University and The Tufts Jonathan constraints limited participation in this initial gathering and M. Tisch College of Civic Life, was hosted and funded by we welcome the future involvement of our colleagues who philanthropists and activists Dr. Michael and Karen Roth- are committed to these issues and already engaged in man. This meeting’s framing impactful projects, nation- question was “Taking into ally and globally. account the current politi- Coming out of this meet- cal direction in our country, ing, we see opportunities and rising authoritarian to expand and deepen tendencies globally, how can national and international we—as musicians, activists, engagement with music and scholars—leverage our and social justice by work- research, teaching, per- ing within the established formance, and activism to structures of academic develop and intensify social and professional organiza- justice initiatives with local tions. An important goal of and global impact?” our retreat was to begin This small gathering of discussing and develop- seventeen colleagues, musi- ing projects that could cians, and activists had am- have a significant national bitious goals. -

An Approach to the Pedagogy of Beginning Music Composition: Teaching Understanding and Realization of the First Steps in Composing Music

AN APPROACH TO THE PEDAGOGY OF BEGINNING MUSIC COMPOSITION: TEACHING UNDERSTANDING AND REALIZATION OF THE FIRST STEPS IN COMPOSING MUSIC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Vera D. Stanojevic, Graduate Diploma, Tchaikovsky Conservatory ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Donald Harris, Adviser __________________________ Professor Patricia Flowers Adviser Professor Edward Adelson School of Music Copyright by Vera D. Stanojevic 2004 ABSTRACT Conducting a first course in music composition in a classroom setting is one of the most difficult tasks a composer/teacher faces. Such a course is much more effective when the basic elements of compositional technique are shown, as much as possible, to be universally applicable, regardless of style. When students begin to see these topics in a broader perspective and understand the roots, dynamic behaviors, and the general nature of the different elements and functions in music, they begin to treat them as open models for individual interpretation, and become much more free in dealing with them expressively. This document is not designed as a textbook, but rather as a resource for the teacher of a beginning college undergraduate course in composition. The Introduction offers some perspectives on teaching composition in the contemporary musical setting influenced by fast access to information, popular culture, and globalization. In terms of breadth, the text reflects the author’s general methodology in leading students from basic exercises in which they learn to think compositionally, to the writing of a first composition for solo instrument. -

The History of the Louisiana State University School of Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1968 The iH story of the Louisiana State University School of Music. Charlie Walton Roberts Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Roberts, Charlie Walton Jr, "The iH story of the Louisiana State University School of Music." (1968). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1458. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1458 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-16,326 ROBERTS, Jr., Charlie Walton, 1935- THE HISTORY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE UNIVER SITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ed.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education i n The Department of Education by Charlie Walton Roberts, Jr. B.Mu.Ed., Louisiana State University, 1957 M.A., Louisiana Polytechnic Institute, 1964 May, 1968 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author acknowledges with gratitude the assistance of Dr. William M. Smith, his major professor, for his guidance throughout this study and his graduate program at Louisiana State University. -

Music Associate of Arts Transfer Degree

Music Associate of Arts Transfer Degree The Associate of Arts for Transfer (AA-T) in Music develops a well-rounded musician. Students who pursue this degree will have guaranteed admission to a California State University (CSU) campus upon successful completion of the specified program requirements. This degree provides students with transfer preparation and pre-professional training. Students should consult with a counselor to determine whether this degree is the best option for their transfer goals. The Associate in Arts for Transfer (AA-T) or the Associate in Science for Transfer (AS-T) is intended for students who plan to complete a bachelor's degree in a similar major at a CSU campus. Students completing these degrees (AA-T or AS-T) are guaranteed admission to the CSU system, but not to a particular campus or major. To earn a music AA-T degree, students must complete the following Associate Degree for Transfer requirements: • completion of the following major requirements with grades of C or better; • completion of a minimum of 60 CSU transferable semester units with a grade point average of at least 2.0; and • certified completion of the CSU General Education-Breadth (CSU-GE) or Intersegmental General Education Transfer Curriculum (IGETC) for CSU, which requires a minimum of 37-39 units. It is highly recommend that students complete courses that satisfy the U.S. History, Constitution, and American Ideals requirement as part of CSU-GE or IGETC before transferring to a CSU. Students planning to transfer to a baccalaureate institution and major in Music should consult with a counselor regarding the transfer process and lower division requirements. -

School of Music 1

School of Music 1 specific degree requirements below) and the foundation general School of Music education courses (a First Year Seminar, taken in the first semester, a quantitative reasoning course, and students must fulfill the university- wide writing requirement consisting of the completion of 4 Writing Mission Enhanced courses along the course of the degree completion). At The School of Music is committed to teaching students to... the end of the sophomore year, each student's record is reviewed by the faculty to determine eligibility for junior status; students must • become critical thinkers, effective leaders and literate, competent pass a sophomore decision jury at that time in order to be eligible for musicians; upper division study in their performance area. An oral competency • exhibit significant proficiency in areas of specialization, developed examination is also taken at the sophomore decision jury, which must through individualized study; be passed or replaced by taking an approved oral communications • work collaboratively with faculty and peers in experiences centered class. All students complete a senior recital or a senior project specific on student needs, goals and aspirations; to their major. • embrace enriching life values and ethical practices; and Recitals • practice individual responsibility for lifelong learning and for supporting and participating in the arts, artistic endeavors and Music majors must appear in general student recitals at least once artistic entities. each semester, with the exception of the -

A History of the School of Music

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1952 History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952) John Roswell Cowan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cowan, John Roswell, "History of the School of Music, Montana State University (1895-1952)" (1952). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2574. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2574 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI A KCSTOHY OF THE SCHOOL OP MUSIC MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY (1895-1952) by JOHN H. gOWAN, JR. B.M., Montana State University, 1951 Presented In partial fulfillment of the requirements for tiie degree of Master of Music Education MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1952 UMI Number EP34848 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, If material had to be removed, a note will Indicate the deletion. -

Iphigénie En Tauride

Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride CONDUCTOR Tragedy in four acts Patrick Summers Libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard, after a work by Guymond de la Touche, itself based PRODUCTION Stephen Wadsworth on Euripides SET DESIGNER Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm Thomas Lynch COSTUME DESIGNER Martin Pakledinaz LIGHTING DESIGNER Neil Peter Jampolis CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Iphigénie en Tauride was Daniel Pelzig made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon. Additional funding for this production was provided by Bertita and Guillermo L. Martinez and Barbara Augusta Teichert. The revival of this production was made possible by a GENERAL MANAGER gift from Barbara Augusta Teichert. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Iphigénie en Tauride is a co-production with Seattle Opera. 2010–11 Season The 17th Metropolitan Opera performance of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Iphigénie en This performance is being broadcast Tauride live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Conductor Opera Patrick Summers International Radio Network, in order of vocal appearance sponsored by Toll Brothers, Iphigénie America’s luxury Susan Graham homebuilder®, with generous First Priestess long-term Lei Xu* support from Second Priestess The Annenberg Cecelia Hall Foundation, the Vincent A. Stabile Thoas Endowment for Gordon Hawkins Broadcast Media, A Scythian Minister and contributions David Won** from listeners worldwide. Oreste Plácido Domingo This performance is Pylade also being broadcast Clytemnestre Paul Groves** Jacqueline Antaramian live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on Diane Agamemnon SIRIUS channel 78 Julie Boulianne Rob Besserer and XM channel 79. Saturday, February 26, 2011, 1:00–3:25 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

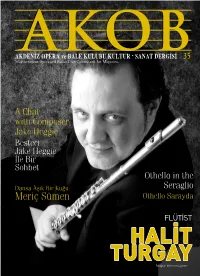

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

Renée Fleming Sings Her First La Traviata

DAVID GOCKLEY, GENERAL DIRECTOR PATRICK SUMMERS, MUSIC DIRECTOR Subscribe Now! 2002–2003 Season Renée Fleming sings her first La Traviata. See it FREE when you SUBSCRIBE NOW! DHoustonivas,divas,divas! Grand Opera celebrates “The Year of the Diva.” Renée Fleming will at long last sing her first Violetta—and, where might this Experience all the anticipated debut happen? The Met? La Scala? Vienna? No, Renée has chosen to excitement and premiere this significant role here at Houston Grand Opera. In a year of firsts— Susan Graham’s first Ariodante and The Merry Widow and Elizabeth Futral’s benefits of a full first Manon—Ms.Fleming’s Violetta will be a defining moment in the world of opera. season subscription: The season begins with the return of Ana Maria Martinez as Mimi in Puccini’s • Free parking beloved La Bohème. Laura Claycomb,the young Te x a s soprano who had • Free subscription to audiences on their feet in this season’s Rigoletto,will return in Donizetti’s Scottish Opera Cues magazine masterpiece, Lucia di Lammermoor.The season closes with the world premiere of • Free season preview The Little Prince,when Oscar-winning composer Rachel Portman turns Antoine CD or cassette de Saint-Exupéry’s much loved novel into a magical and moving opera. • Free lost ticket replacement Extraordinary singers in extraordinary productions.As a full season subscriber, • Exchange privileges you get 7 operas for the price of 6. That means you can see Renée Fleming’s debut • 10% discount on as Violetta for free! I urge you to take advantage of this offer, it’s the only way we additional tickets can guarantee you a seat. -

2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall

The Complete Recitalist June 9-23 n Singing On Stage June 18-July 3 n Distinguished faculty John Harbison, Jake Heggie, Martin Katz, and others 2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall Welcome to Songfest 2005! “Search and see whether there is not some place where you may invest your humanity.” – Albert Schweitzer 1996 Young Artist program with co-founder John Hall. Songfest 2005 is supported, in part, by grants from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music and the Virgil Thomson Foundation. Songfest photography courtesy of Luisa Gulley. Songfest is a 501(c)3 corporation. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent permitted by law. Dear Friends, It is a great honor and joy for me to present Songfest 2005 at Pepperdine University once again this summer. In our third year of residence at this beautiful ocean-side Malibu campus, Songfest has grown to encompass an ever-widening circle of inspiration and achievement. Always focusing on the special relationship between singer and pianist, we have moved on from our unique emphasis on recognized masterworks of art song to exploring the varied and rich American Song. We are once again privileged to have John Harbison with us this summer. He has generously donated a commission to Songfest – Vocalism – to be premiered on the June 19 concert. Our singers and pianists will be previewing his new song cycle on poems by Milosz. Each time I read these beautiful poems, I am reminded why we love this music and how our lives are enriched. What an honor and unique opportunity this is for Songfest. -

American Mezzo Soprano, Lindsay Kate Brown, Is Quickly Making Her Mark in the World of Opera

Praised for her "...lustrous, warm and deep [sound]..." American mezzo soprano, Lindsay Kate Brown, is quickly making her mark in the world of opera. For her 2020-2021 season, Ms. Brown returned for her final season at Houston Grand Opera as a third year Studio Artist. Ms. Brown was scheduled to make her role debut as Mercédès in Bizet’s Carmen under the direction of Maestra Eun Sun Kim, cover the role of Charlotte in Massenet’s Werther, perform the roles of Knappen and Zaubermädchen in Wagner’s Parsifal under the baton of Maestro Patrick Summers as well as cover the role of Kundry, but, unfortunately all performances were cancelled due to COVID-19. The spring of 2021 was “filled with the sounds of music” in a review of Rodgers’ and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music entitled My Favorite Things where Ms. Brown sang Sister Berthe and Chant Leader and covering Mother Abbess under Maestro Richard Bado. As part of HGO’s new Digital Season, Ms. Brown made her role debut as Gertrude in Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel as well as performed in a number of scenes for the annual Studio Showcase. This summer, Ms. Brown will join Santa Fe Opera as an Apprentice Artist where she will perform the roles of Hippolyta in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, conducted by Maestro Harry Bicket and Marcellina in Laurent Pelly’s new production of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, among other duties. For the 2019-2020 season, Ms. Brown returned to Houston to make her Houston Grand Opera stage debut as Giovanna in Tomer Zvulun’s production of Verdi’s Rigoletto. -

PROGRAM BOOK September 2020 CONTENTS FWSO STAFF

fwsoFort Worth Symphony Orchestra Stewart Goodyear at Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium Sept. 18-20 PROGRAM BOOK September 2020 CONTENTS FWSO STAFF 2 Letter from the Chairman EXECUTIVE OFFICE Keith Cerny, Ph.D., President and CEO 3 Letter from the President & CEO Diane Bush, Executive Assistant and Board Secretary ARTISTIC OPERATIONS 4 About Robert Spano Becky Tobin Vice President of Artistic Operations and COO Douglas Adams Orchestra Librarian 5 Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra Roster James Andrewes Assistant Librarian Kelly Ott Artistic Manager 6 Program 1 :: Sep. 11—13, 2020 Victoria Paarup Artistic Operations Coordinator Jacob Pope Production Manager Artist Profile: Lisa Stallings Director of Operations Asleep at the Wheel Brenda Tullos Orchestra Personnel Manager Taylor Vogel Director of Education and Community Programs The Quebe Sisters DEVELOPMENT 11 Program 2 :: Sep 18—20, 2020 Julie Baker Vice President of Development Artist Profile: Kara Allan Endowment Campaign Manager Mary Byrd Development Coordinator Rossini, Saint-Saëns, and Mendelssohn Tyler Murphy Gifts Officer Patrick Summers Jonathan Neumann Director of Special Events Stewart Goodyear FINANCE David Sanders Vice President of Finance and CFO 18 Executive Committee Latonja Scott Finance Manager Rebecca Clark Finance and Benefits Assistant 19 Board of Directors HUMAN RESOURCES 34 Arts Council of Fort Worth Jacque Carpenter Director of Human Resources MARKETING Carrie Ellen Adamian Chief Marketing Officer Jennifer Aprea Patron Development Center Manager Melanie Boma Ticket Services Manager Stephen Borodkin Ticket Services Representative Katie Kelly Communications Manager Dan Meagher Director of Single Ticket Promotions McKalah Robinson Ticket Services Representative TECHNOLOGY Scott Griffitts Vice President of Technology 1 | 2020/2021 SEASON LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN MERCEDES T.