TWT Response to the Planning White Paper: Planning for the Future October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knettishall Leaflet Dog Walkers 29.Indd

Suffolk Wildlife Trust Direct Debit Instruction to your Bank or Building Society to pay by Direct Debit. Please fill in the form and return it to Suffolk Wildlife Trust. The high piping melody of skylarks in the Name and full address of your Bank or Building Society skies over Knettishall Heath is one of the To the manager of: Bank/Building Society sounds of summer. During the nesting Dogs & ground nesting birds at season, dog walkers can help to protect Address these glorious little birds by avoiding the open heath. Knettishall Heath Names(s) of account holder(s) Up to 12 pairs of skylark nest here and we hope nightjar will return to breed. Both species nest on the ground and will abandon their nest if disturbed by dogs. Bank/Building Society account number Service user number With over 400 acres at Knettishall Heath, there is plenty of space for visitors and birds Walking with your dog at 7 2 – so for a few months each year Branch sort code Reference (SWT use only)4 8 6 5 ask dog walkers to keep to less sensitive we areas whilst the birds are on their nests. Instruction to your Bank or Building Society How you can help Please pay Suffolk Wildlife Trust Direct Debits from the account detailed in this The bird nesting season is from early Knettishall Instruction subject to the safeguards assured by The Direct Debit Guarantee. I March to late August. During this time understand that this Instruction may remain with Suffolk Wildlife Trust and, if so, details will be passed electronically to my Bank/Building Society. -

Sussex Wildlife Trust

s !T ~ !I ~ !f ~ !I THE SUSSEX RECORDER !f ~ !I Proceedings from the !l Biological Recorders' Seminar ?!I held at !!I the Adastra Hall, Hassocks ~ February 1996. !I ~ !I Compiled and edited by Simon Curson ~ ~ ~ !I ~ !I ~ Sussex Wildlife Trust :!f Woods Mill Sussex ~ ·~ Henfield ,~ ~ West Sussex Wildlife ;~ BN5 9SD TRUSTS !f ~ -S !T ~ ~ ~ !J ~ !J THE SUSSEX RECORDER !f !I !I Proceedings from the !I Biological Recorders' Seminar ?!I held at ~ the Adastra Hall, Hassocks ~ February 1996. !I ~ !I Compiled and edited by Simon Curson ~ ~ "!I ~ ~ !I Sussex Wildlife Trust ~ Woods Mill Sussex ~ ·~ Benfield ~ -~ West Sussex ~ Wildlife BN5 9SD TRUSTS ~ ~ .., ~' ~~ (!11 i JI l CONTENTS f!t~1 I C!! 1 Introduction 1 ~1 I ) 1 The Environmental Survey Directory - an update 2 I!~ 1 The Sites of Nature Conservation Importance (SNCI) Project 4 f!11. I The Sussex Rare Species Inventory 6 I!! i f!t I Recording Mammals 7 • 1 I!: Local Habitat Surveys - How You can Help 10 I!~ Biological Monitoring of Rivers 13 ~! Monitoring of Amphibians 15 I!! The Sussex SEASEARCH Project 17 ~·' Rye Harbour Wildlife Monitoring 19 r:! Appendix - Local Contacts for Specialist Organisations and Societies. 22 ~ I'!! -~ J: J~ .~ J~ J: Je ISBN: 1 898388 10 5 ,r: J~ J Published by '~i (~ Sussex Wildlife Trust, Woods Mill, Henfield, West Sussex, BN5 9SD .~ Registered Charity No. 207005 l~ l_ l~~l ~-J'Ii: I ~ ~ /~ ~ Introduction ·~ !J Tony Whitbread !! It is a great pleasure, once again, to introduce the Proceedings of the Biological !l' Recorders' Seminar, now firmly established as a regular feature of the biological year in Sussex. -

Sussex Wildlife Trust

E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y The Natii • body, responsi from floodinj tion, conservati Wales, N RA Soui NATIONAL LIBRARY & and the INFORMATION SERVICE SOUTHERN REGION Guildbourne House. Chatsworth Road, Worthing. West Sussex Bin! 1 1LD \ w ’ NRA National Riven Authority Southern Region Regional Office Guildbourne Ffouse Chatsworth Road Worthing West Sussex BN 11 1LD Tel. (0903) 820692 «o in.oi.Bnn . a t i f i r ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 0 4 5 5 1 9 Soc>l-Vv-em l i e > NRA National Rivers Authority Southern Region W ater W ise Awards for Sussex Schools CO-SPONSORS Sussex wildlife TRUSTS S o u t h e r n J m "nr WHAT IS WATER WISE? Water Wise is an environmental award scheme funded by the National Rivers Authority Southern Region (NRA). It aims to encourage teachers to raise awareness of the importance of water in the environment among Sussex school children. The scheme is being organised in conjunction with the Sussex Wildlife Trust. As Guardians of the Water Environment, the NRA works to ensure that all sectors of the community appreciate the value of rivers, streams, ponds and marshes for wildlife and people. By promoting water awareness among school children and their communities, the N RA is investing in the long term protection of our environment. Sussex Wildlife Trust also recognises that wetlands support a wide variety of plant and animal life, which makes them an ideal educational resource. i0 t Sussex wildlife TRUSTS The Sussex Wildlife Trust is a registered charity founded in 1961 and devoted to the conservation of the natural heritage of Sussex. -

The Direct and Indirect Contribution Made by the Wildlife Trusts to the Health and Wellbeing of Local People

An independent assessment for The Wildlife Trusts: by the University of Essex The direct and indirect contribution made by The Wildlife Trusts to the health and wellbeing of local people Protecting Wildlife for the Future Dr Carly Wood, Dr Mike Rogerson*, Dr Rachel Bragg, Dr Jo Barton and Professor Jules Pretty School of Biological Sciences, University of Essex Acknowledgments The authors are very grateful for the help and support given by The Wildlife Trusts staff, notably Nigel Doar, Cally Keetley and William George. All photos are courtesy of various Wildlife Trusts and are credited accordingly. Front Cover Photo credits: © Matthew Roberts Back Cover Photo credits: Small Copper Butterfly © Bob Coyle. * Correspondence contact: Mike Rogerson, Research Officer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester CO4 3SQ. [email protected] The direct and indirect contribution made by individual Wildlife Trusts on the health and wellbeing of local people Report for The Wildlife Trusts Carly Wood, Mike Rogerson*, Rachel Bragg, Jo Barton, Jules Pretty Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Introduction 8 1.1 Background to research 8 1.2 The role of the Wildlife Trusts in promoting health and wellbeing 8 1.3 The role of the Green Exercise Research Team 9 1.4 The impact of nature on health and wellbeing 10 1.5 Nature-based activities for the general public and Green Care interventions for vulnerable people 11 1.6 Aim and objectives of this research 14 1.7 Content and structure of this report 15 2. Methodology 16 2.1 Survey of current nature-based activities run by individual Wildlife Trusts and Wildlife Trusts’ perceptions of evaluating health and wellbeing. -

Countryside Jobs Service Weekly® the Original Weekly Newsletter for Countryside Staff First Published July 1994

Countryside Jobs Service Weekly® The original weekly newsletter for countryside staff First published July 1994 Every Friday : 15 March 2019 News Jobs Volunteers Training CJS is endorsed by the Scottish Countryside Rangers Association and the Countryside Management Association. Featured Charity: Canal and River Trust www.countryside-jobs.com [email protected] 01947 896007 CJS®, The Moorlands, Goathland, Whitby YO22 5LZ Created by Anthea & Niall Carson, July ’94 Key: REF CJS reference no. (advert number – source – delete date) JOB Title BE4 Application closing date IV = Interview date LOC Location PAY £ range - usually per annum (but check starting point) FOR Employer Main text usually includes: Description of Job, Person Spec / Requirements and How to apply or obtain more information CJS Suggestions: Please check the main text to ensure that you have all of the required qualifications / experience before you apply. Contact ONLY the person, email, number or address given use links to a job description / more information, if an SAE is required double check you use the correct stamps. If you're sending a CV by email name the file with YOUR name not just CV.doc REF 698-ONLINE-29/3 JOB SENIOR SITE MANAGER BE4 29/3/19 LOC SALISBURY, WILTSHIRE PAY 35000 – 40000 FOR FIVE RIVERS ENVIRONMENTAL CONTRACTING You will be joining a staff of 30 people working all over the UK delivering a variety of environmental projects including small civil engineering projects, river restoration, river re-alignment, floodplain re-connection, ecological mitigation & fish passes. Responsibilities include: line manage the delivery of two projects, support two Site Foreman & act as a mentor; spend a min of 2 days a week in the office (Meadow Barn or the Site Offices) to assist with planning, project management, development of RAMS & assisting the costing department; ensure all H&S legislation is complied with onsite; recruitment. -

Annual Report & Accounts 2012-13

Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts Annual Report & Accounts 2012/13 Registered charity number: 207238 Version: 07/10/2013 10:17:20 Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts CONTENTS for the year ended 31 March 2013 Page Chair‟s Report 2 Chair of TWT England‟s Report 3 Trustees‟ Report 4-19 Auditor‟s Report 20-21 Accounting Policies 22-23 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 24 Consolidated and Society Balance Sheets 25 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 26 Notes to the Financial Statements 27-39 The following pages do not form part of the statutory financial statements: Appendix: Grant Expenditure by Organisation 40-47 Page | 1 Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts CHAIR‟S REPORT for the year ended 31 March 2013 It has been an „eventful‟ year for me, my first as appointment. It is clear that the movement owes Chair of our 100-year-old movement. It all started them a great debt. with a bang - our tremendous centenary celebration at the Natural History Museum. At this It seems to me that this dynamic, creative event we traced our history back to our founder, movement is as united and effective as ever. Charles Rothschild, and awarded our medal in his, and his daughter Miriam‟s name, to philanthropist Peter De Haan. There were other occasions for celebration as well, including Sir David Attenborough presenting our centenary medal to Ted Smith, the father of the modern Wildlife Trust movement. There was also a gathering of one hundred of our most committed people from across the UK at Highgrove where our Patron HRH The Prince of Wales recognised their achievements. -

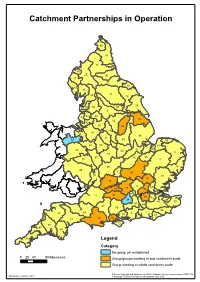

Catchment Partnerships in Operation

Catchment Partnerships in Operation 100 80 53 81 89 25 90 17 74 26 67 33 71 39 16 99 28 99 56 95 2 3 20 30 37 18 42 42 85 29 79 79 15 43 91 96 21 83 38 50 61 69 51 51 59 92 62 6 73 97 45 55 75 7 88 24 98 8 82 60 10 84 12 9 57 87 77 35 66 66 78 40 5 32 78 49 35 14 34 49 41 70 94 44 27 76 58 63 1 48 23 4 13 22 19 46 72 31 47 64 93 Legend Category No group yet established 0 20 40 80 Kilometres GSurobu cpa/gtcrhomupesn wt orking at sub catchment scale WGrhooulpe wcaotrckhinmge antt whole catchment scale © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. Ordnance Survey licence number 100024198. Map produced October 2013 © Copyright Environment Agency and database right 2013. Key to Management Catchment ID Catchment Sub/whole Joint ID Management Catchment partnership catchment Sub catchment name RBD Category Host Organisation (s) 1 Adur & Ouse Yes Whole South East England Yes Ouse and Adur Rivers Trust, Environment Agency 2 Aire and Calder Yes Whole Humber England No The Aire Rivers Trust 3 Alt/Crossens Yes Whole North West England No Healthy Waterways Trust 4 Arun & Western Streams Yes Whole South East England No Arun and Rother Rivers Trust 5 Bristol Avon & North Somerset Streams Yes Whole Severn England Yes Avon Wildlife Trust, Avon Frome Partnership 6 Broadland Rivers Yes Whole Anglian England No Norfolk Rivers Trust 7 Cam and Ely Ouse (including South Level) Yes Whole Anglian England Yes The Rivers Trust, Anglian Water Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife 8 Cherwell Yes Whole Thames England No Trust 9 Colne Yes Whole Thames England -

Manage Invasive Species

CASE STUDY Manage invasive species Project Summary Title: Pevensey Floating Pennywort Control Trials Location: Pevensey, East Sussex, England Technique: Herbicide spraying of invasive species Cost of technique: ££ Overall cost of scheme: ££ Benefits: ££ Dates: 2010-2011 Mitigation Measure(s) Manage invasive species Sensitive techniques for managing vegetation (beds and banks) How it was delivered Delivered by: Environment Agency Partners: Sussex Wildlife Trust; Natural England, Royal Floating pennywort in Hurt Haven, 2010 HaskoningDHV All images © Environment Agency copyright and database rights 2013 Background and issues Pevensey Levels consist of a large area of low-lying In order to develop a practicable method for the control of grazing meadows intersected by a complex system of floating pennywort, Natural England and the Environment ditches. The Levels are a designated a Site of Special Agency established experimental trials at the Pevensey Scientific interest (SSSI) and a Ramsar wetland of Levels to address the above issues, as a pilot study on international importance due to the invertebrate and options for the management of this invasive aquatic plant plant assemblages found on the site, which include one within a Site of Special Scientific Interest. nationally rare and several nationally scarce aquatic plants, and many nationally rare invertebrates. Floating pennywort is classified as a non-native invasive species in the UK and is listed under Part II of Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with respect to England, Wales and Scotland. Surveys in 2008 confirmed the presence of the perennial and stoloniferous (i.e. spreads via horizontal stems) floating pennywort extending to approximately 10% of the watercourses on the Levels. -

Sussex Wildlife Trust

Sussex Wildlife Trust Woods Mill, Henfield, West Sussex BN5 9SD Telephone: 01273 492630 Facsimile: 01273 494500 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sussexwt.org.uk WildCall: 01273 494777 Peter Earl Team Manager, Planning Development Control Your ref: RR/22474/CC(EIA) East Sussex County Council County Hall St Anne's Crescent LEWES East Sussex BN7 1UE 13 November 2008 Dear Mr Earl Bexhill Hastings Link Road Planning Application Addendum to Environmental Statement Thank you for advising us about further documents related to the above planning application. Sussex Wildlife Trust maintains a strong objection to this planning application on the grounds of environmental damage and therefore the unsustainability of the proposed scheme. Our main criticism of the approach to ecological studies is that a holistic assessment would clearly show the damaging nature of this proposal to the whole valley and its ecological and hydrological functioning. This has still not been acknowledged or addressed. Even when considering the impact on the Sites of Special Scientific Interest the whole site is not assessed, instead individual issues are picked apart in an attempt to mitigate without assessing the resulting and indirect effects on other features, or again ecological functioning. The long term effects of disturbance and pollution will affect the whole valley, if not directly within the zone of influence then indirectly, potentially altering species assemblages and interactions, functioning etc. We still do not have clarity or confidence in the mitigation plans proposed but believe that it is vital that long term monitoring programmes are established along with contingency planning. Without this the mitigation scheme may be implemented regardless of its success or failure. -

Our Special 50Th Birthday Issue

FREE CoSuaffoslk t & Heaths Spring/Summer 2020 Our Special 50th Birthday Issue In our 50th birthday issue Jules Pretty, author and professor, talks about how designation helps focus conservation and his hopes for the next 50 years, page 9 e g a P e k i M © Where will you explore? What will you do to conserve our Art and culture are great ways to Be inspired by our anniversary landscape? Join a community beach inspire us to conserve our landscape, 50 @ 50 places to see and clean or work party! See pages 7, and we have the best landscape for things to do, centre pages 17, 18 for ideas doing this! See pages 15, 18, 21, 22 www.suffolkcoastandheaths.org Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty • 1 Your AONB ur national Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty are terms of natural beauty, quality of life for residents and its A Message from going to have a year to remember and it will be locally associated tourism industry. See articles on page 4. Osignificant too! In December 2019 the Chair’s from all the AONBs collectively committed the national network to The National Association for AONBs has recently published a Our Chair the Colchester Declaration for Nature, and we will all play position statement relating to housing, and the Government has our part in nature recovery, addressing the twin issues of updated its advice on how to consider light in the planning wildlife decline and climate change. Suffolk Coast & Heaths system. AONB Partnership will write a bespoke Nature Recovery Plan and actions, and specifically champion a species to support We also look forward (if that’s the right term, as we say its recovery. -

Public Engagement and Wildlife Recording Events in the UK Matt Postles & Madeleine Bartlett, Bristol Natural History Consortium

- DRAFT - The rise and rise of BioBlitz: public engagement and wildlife recording events in the UK Matt Postles & Madeleine Bartlett, Bristol Natural History Consortium Abstract A BioBlitz is a collaborative race against the clock to discover as many species of plants, animals and fungi as possible, within a set location, over a defined time period - usually 24 hours. A BioBlitz usually combines the collection of biological records with public engagement as experienced naturalists and scientists explore an area with members of the public, volunteers and school groups. The number of BioBlitz events taking place in the UK has increased explosively since the initiation of the National BioBlitz programme in 2009 attracting large numbers of people to take part and gathering a large amount of biological data. BioBlitz events are organised with diverse but not mutually exclusive aims and objectives and the majority of events are considered successful in meeting those aims. BioBlitz events can cater for and attract a wide diversity of participants through targeted activities, particularly in terms of age range, and (in the UK) have engaged an estimated 2,250 people with little or no prior knowledge of nature conservation in 2013. BioBlitz events have not been able to replicate that success in terms of attracting participants from ethnic minority groups. Key positive outcomes for BioBlitz participants identified in this study include enjoyment, knowledge and skills based learning opportunities, social and professional networking opportunities and inspiring positive action Whilst we know that these events generate a lot of biological records, the value of that data to the end user is difficult to quantify with the current structure of local and national recording schemes. -

Reversing the Decline of Insects

A new report from the Wildlife Trusts Reversing the Decline of Insects Lead Author: Professor Dave Goulson, University of Sussex Reversing the Decline of Insects Contributors Contents Foreword Lead Author: Professor Dave Goulson, University of Sussex Craig Bennett, on behalf of Foreword 3 Professor of Biology and specialising in bee ecology, The Wildlife Trusts Executive Summary 4 he has published more than 300 scientific articles on the ecology and conservation of bumblebees Introduction 5 and other insects. Section 1: Insect Recovery Networks 6 s a five-year-old boy when I left Section 2: Insects in the Farmed Landscape 12 Editorial Group: my light on at night with the Penny Mason, Devon Wildlife Trust window open, my bedroom Section 3: Insects in our Towns and Cities 18 Ellie Brodie, The Wildlife Trusts A would be swarming with moths half Section 4: Insects in our Rivers and Streams 24 Sarah Brompton, Action for Insects Campaign Manager Imogen Davenport, Dorset Wildlife Trust an hour later. Section 5: Insect Champions 32 Steve Hussey, Devon Wildlife Trust Conclusion 37 Gary Mantle, Wiltshire Wildlife Trust Now, I’d be lucky to see one. When venturing away for a family Joanna Richards, The Wildlife Trusts holiday, driving up the A1 for five hours, the front number plate The Wildlife Trusts’ Asks 39 would be covered in squashed insects by the time we arrived at our destination. Now, there might be one or two. With thanks to the many contributors Alice Baker, Wiltshire Wildlife Trust Today, I’m 48 years old and the science is clear; in my lifetime Tim Baker, Charlton Manor Primary School 41% of wildlife species in UK have suffered strong or moderate Jenny Bennion, Lancashire Wildlife Trust decreases in their numbers – be it number of species, or Janie Bickersteth, Incredible Edible Lambeth number of individuals within a species, and it is insects that Leigh Biagi, On the Verge Stirling have suffered most.