Bamburgh Castle Project Design Excavation Season 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Castle Wynd Bamburgh, Northumberland

1 Castle Wynd Bamburgh, Northumberland Shared ownership bungalow in popular coastal village Semi detached bungalow Two bedrooms Lounge Kitchen 4-6 Market Street Alnwick Bathroom NE66 1TL Garden to front and rear Tel: 01665 603581 Easy access to village amenities Fax: 01665 510872 80% share to be bought www.georgefwhite.co.uk A member of the George F White Group Fixed Price: £124,000 The Area The master bedroom is a double room with Bamburgh is an extremely popular coastal village window overlooking the front of the garden. located in the heart of the North Northumberland Further single bedroom with window overlooking coastline. The village has restaurants and hotels, the rear garden. The bathroom is fitted with a gift shops, butchers and Bamburgh Castle which suite in beige comprising of low level wc, is a fantastic tourist attraction. panelled bath with electric shower over, pedestal wash hand basin. Partially tiled walls and window The nearby fishing village of Seahouses has to rear. further amenities including First and Middle schools, doctors, dentists, petrol station and Externally supermarket. There is a bus service which There is a garden to front which is mainly laid to travels through Bamburgh and travels north to lawn with borders and path leading to the front Berwick and south to Alnwick. Nearby Berwick door. The rear garden is paved for low upon Tweed and Alnmouth railway stations give maintenance with borders. links for the East Coast mainline and direct to London and Edinburgh. The Property We are offering an 80% share in this bungalow which is ideally situated in one of Northumberlands most popular villages. -

Northumberland Visitor Survey 2013

NORTHUMBERLAND VISITOR SURVEY 2013 1 1. INTRODUCTION In 2005/06 One North East carried out the first region wide visitor survey for North East England to establish baseline profiles of tourists to the region. The survey was repeated in 2008 and again in 2010 to establish any changes in consumer demographics or behaviours. Following the abolition of the RDA’s the Northern Tourism Alliance recognised the importance of ensuring we have the most up to date information possible on our visitors and chose to come together to fund visitor survey interviews in 2013. This report summarises the findings for the interviews undertaken in Northumberland. The key objectives of the survey were to: To inform development decisions for Durham and the North East Understand visitor satisfaction and identify areas for improvement Understand people’s motivation for visiting Gather visitor profiles such as demographics, booking sources, use of the internet etc Gather economic expenditure data to feed into economic impact reports We received a total return of 334 completed surveys which were a mixture of online responses and surveys completed at attractions such as Woodhorn and Bamburgh Castle. 2 2. KEY FINDINGS Visitor Profiles 59% of visitors to Northumberland are staying overnight. 16% of visitors are new visitors while more than 1/3rd have been more than 20 times before. 41% of visitors said their main reason for visit was to visit heritage sites. General sightseeing and visiting artistic or heritage exhibits also came out highly. 9 out of 10 visitors use their own car to travel to Northumberland Previous visits to the region play a significant role in visitors choosing to return. -

An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2017 An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England Julie Polcrack Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Polcrack, Julie, "An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England" (2017). Master's Theses. 1510. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1510 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND by Julie Polcrack A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The Medieval Institute Western Michigan University August 2017 Thesis Committee: Jana Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Robert Berkhofer, Ph.D. Graeme Young, B.Sc. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND Julie Polcrack, M.A. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALMNS HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Sea shanties were working songs which helped sailors move in unison on manual tasks like hauling the anchor or hoisting sails; they also served to raise spirits. Songs were usually led by a shantyman who sang the verses with the sailors joining in for the chorus. Taking inspiration from these traditional songs, as well as those with a modern nautical connection, this break allows you to lend your voice to create beautiful harmonies singing as part of a group. Join us to sing with a tidal rhythm and flow and experience the joy of singing in unison. With a beachside location in sight of the sea, we might even take our singing outside to see what the mermaids think! WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality Full Board en-suite accommodation and excellent food in our Country House • Guidance and tuition from a qualified leader, to ensure you get the most from your holiday • All music HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Relaxed informal sessions • An expert leader to help you get the most out of your voice! • Free time in the afternoons www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 ACCOMMODATION Nether Grange Sitting pretty in the centre of the quiet harbour village of Alnmouth, Nether Grange stands in an area rich in natural beauty and historic gravitas. There are moving views of the dramatic North Sea coastline from the house too. This one-time 18th century granary was first converted into a large family home for the High Sheriff of Northumberland in the 19th century and then reimagined as a characterful hikers’ hotel. -

Full Index Covering Bulletin 1 to Journal

DCLHS INDEX TO Bulletin 1-69 & Journal 70 (c) 2009 INDEX The fi rst number is the number of the Bulletin in which the reference can be found; fi gures in brackets are page references. Figures in bold are used to indicate that the subject is the main concern of those pages, or receives substantial treatment, except in cases where the article title is quoted in full. For Bulletins 6 and 7, which originally appeared without pagination, page numbers have been allocated on the same basis as pagination elsewhere. Titles of articles are in italics, titles of books reviewed are in Arial italic. Abbot Memorial Industrial School, Gateshead, The 32(69-74), 50(106) Aberdeen, S., Newton Aycliffe - the Beginning of a New Town 12(42-45) Accidents 52(42-49), 69(3-20) Admiralty jurisdiction (of Bishops of Durham) 23(45-47), 25(40) Aerial photography 14(37-39), 47(101-103) Agricultural labourers 70(21-23) Agriculture 12(1-4), 14(6), 18(33, 39-40), 19(44-47), 21(36-37), 23(12-14, 16-17, 18), 25(31-34), 35(25-36, 39-46), 36(15-16), 46(46-89), 47(50, 57-60, 70), 70(15-31) Alcohol abuse 54(52-65) Aldborough 25(13) Aldin Grange 17(31) Allen, E., Obituary - Charles Philip Neat 20(2-3) Allen, E. (obituary) 29(52-53) Allendale 24(40), 31(13, 15-16), 33(9) Allenheads 18(32) Allison, George 55(14-15) Alnwick 24(40), 38(34-35), 60(12) Alston 15(19, 20), 33(8, 10, 12-13, 15-18) Amble 67(67-69) American Civil War 19(2-8), 46(34-45), 48(48-54) Anderson, E. -

Northumberland Coast AONB

Sustainable Development Fund Sustainable Development Fund Organisation Grant amount Project applications to date 2005/06 A Sense of Place International £10,000 The project will test the opportunities for developing Centre for the the global ecomuseums concept in England, through an Uplands (in APPROVED action research project in the Northern Uplands of conjunction with 2005/06 England. Ecomuseum is a philosophy that has been Leader+ in North adopted worldwide and encompasses a variety of Northumberland) ecological activities that are managed by local people and that aim to develop an entire region as a living museum. St Oswald’s Way Alnwick District £10,000 To establish a long distance walk route that forms the Council final side of a square of long distance walks in APPROVED Northumberland: the others being St Cuthbert’s Way, 2005/06 the Pennine Way and Hadrian’s Way. The walk is 100 miles stretching from Bamburgh to Heavenfield in Tynedale. Golf and Scenic Tours Not Entirely Sure £ 8,225 The project will allow the applicants to buy a London Tours Routemaster Bus to use for golf and scenic tours around APPROVED North Northumberland. A guide will be available to 2005/06 interpret the history and heritage of the AONB. The ground floor will be adapted so that it is suitable for various users. Beadnell to Bamburgh and Glororum path – phase 1(a) Northumberland £22,125 Creation of safe road-side walking and cycling route to County Council link the settlements of Seahouses and Beadnell. The APPROVED scheme will provide a route from Seahouses village to 2005/06 Annstead Farm. -

North East England

Lerwick Kirkwall Dunnet Head Cape Wrath Duncansby Head Strathy Whiten Scrabster John O'Groats Rudha Rhobhanais Head Point (Butt of Lewis) Thurso Durness Melvich Castletown Port Nis (Port of Ness) Bettyhill Cellar Head Tongue Noss Head Wick Gallan Head Steornabhagh (Stornoway) Altnaharra Latheron Unapool Kinbrace Lochinver Helmsdale Hushinish Point Lairg Tairbeart Greenstone (Tarbert) Point Ullapool Rudha Reidh Bonar Bridge Tarbat Dornoch Ness Tain Gairloch Loch nam Madadh Lossiemouth (Lochmaddy) Alness Invergordon Cullen Fraserburgh Uig Cromarty Macduff Elgin Buckie Dingwall Banff Kinlochewe Garve Forres Nairn Achnasheen Torridon Keith Turriff Dunvegan Peterhead Portree Inverness Aberlour Huntly Lochcarron Dufftown Rudha Hallagro Stromeferry Ellon Cannich Grantown- Kyle of Lochalsh Drumnadrochit on-Spey Oldmeldrum Dornie Rhynie Kyleakin Loch Baghasdail Inverurie (Lochboisdale) Invermoriston Shiel Bridge Alford Aviemore Aberdeen Ardvasar Kingussie Invergarry Bagh a Chaisteil Newtonmore (Castlebay) Mallaig Laggan Ballater Banchory Braemar Spean Dalwhinnie Stonehaven Bridge Fort William Pitlochry Brechin Glencoe Montrose Tobermory Ballachulish Kirriemuir Forfar Aberfeldy Lochaline Portnacroish Blairgowrie Arbroath Craignure Dunkeld Coupar Angus Carnoustie Connel Killin Dundee Monifieth Oban Tayport Lochearnhead Newport Perth -on-Tay Fionnphort Crianlarich Crieff Bridge of Earn St Andrews SCOTLAND Auchterarder Auchtermuchty Cupar Inveraray Ladybank Fife Ness Callander Falkland Strachur Tarbet Dunblane Kinross Bridge Elie of Allan Glenrothes -

Traveller's Guide Northumberland Coast

Northumberland A Coast Traveller’s Guide Welcome to the Northumberland Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). There is no better way to experience our extensive to the flora, fauna and wildlife than getting out of your car and exploring on foot. Plus, spending just one day without your car can help to look after this unique area. This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave the confines of your car behind and really get out in our stunning countryside. So, find your independent spirit and let the journey become part of your adventure. Buses The website X18 www.northumberlandcoastaonb.orgTop Tips, is a wealth of information about the local area and things to and through to see and do. and Tourist Information! Berwick - Seahouses - Alnwick - Newcastle Weather Accommodation It is important to be warm, comfortable and dry when out exploring so make sure you have the Berwick, Railway Station Discover days out and walks by bus appropriate kit and plenty of layers. Berwick upon Tweed Golden Square Free maps and Scremerston, Memorial 61 Nexus Beal, Filling Station guide inside! Visit www.Nexus.org.uk for timetables, ticket 4 418 Belford Post Office information and everything you need to know 22 about bus travel in the North East. You can even Waren Mill, Budle Bay Campsite Timetables valid until October 2018. Services are subject to change use the live travel map to see which buses run 32 so always check before you travel. You can find the most up to date Bamburgh from your nearest bus stop and to plan your 40 North Sunderland, Broad Road journey. -

English Spring 1

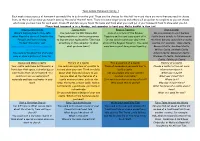

Team Galena Homework Spring 1 Each week choose a piece of homework you would like to do from the grid. These are the choices for this half term and there are more than you need to choose from, so there will be some you haven’t done by the end of the half term. There are some longer pieces and others will be quicker to complete so you can choose which ones you have time for each week. Cross off and date as you finish the tasks and think what you could put in your homework book to show what you did. Please hand homework in on a Monday, and remember to hand your Maths booklet in then too! Staying Safe Online Typing Skills Bayeux Tapestry Visit a Castle We are learning how to stay safe You could use the BBC Dance Mat Look at a picture of the Bayeux We are planning to visit Durham online. Read the story of Smartie the Typing website or similar programme Tapestry and try and copy a part of it. Castle (more details to follow nearer Penguin and learn his song. to improve your typing skills. Then type Or you could record your day in the the time) but you could visit a nearby To hear this story, visit something on the computer to show style of the Bayeux Tapestry. You could castles, for example – Raby Castle, www.childnet.com/resources/smartie- what you have learnt. even have a go at doing some tapestry! Barnard Castle, Auckland Castle, the-penguin Witton Castle, Hexham Castle, You could write about the story and Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, song or draw a picture of Smartie. -

Embleton by Bus

Great days out from Embleton by bus Using Embleton as a starting point, there are some great ways to explore Northumberland without a car. The table below lists the services available and selected running times. Overleaf, are some ideas to help plan your day out, as well as details of lots of discounts available with your bus ticket. Destination Service Change Freque Departure Outward Return Arrival Link to Attractions and things to do number needed? ncy time from arrival departure time in timetable Embleton time time Embleton Alnwick Arriva X18 or No Hourly 09:12 09:53 16:05 16:56 Arriva Alnwick Castle and Gardens, Barter Books Travelsure 418 10:21 10:57 17:08 17:44 X18/418 Bamburgh Arriva X18 or No Hourly 09:44 10:17 15:50 16:21 Arriva Bamburgh Castle, Grace Darling Museum Travelsure 418 10:46 11:16 16:32 17:03 X18/418 Beadnell Arriva X18 or No Hourly 09:44 10:00 15:11 15:22 Arriva Beadnell Bay, watersports, little terns Travelsure 418 10:46 10:57 17:21 17:32 X18/418 Berwick Arriva X18 No Five 08:31 09:45 16:15 17:32 ArrivaX18 Barracks, Ramparts, Royal Border Bridge per day 10:46 12:00 18:15 19:32 Craster Arriva X18 or No Hourly 09:12 09:22 15:34 15:44 Arriva Dunstanburgh Castle, harbour, kippers Travelsure 418 10:21 10:31 16:46 16:56 X18/418 Holy Island Arriva X18 Yes, Perry- Weds Varies, depending on tide times. Check online for ArrivaX18 Lindisfarne Castle, Priory, Heritage Centre man’s 477 & Fri* exact times and see overleaf for more details. -

4-Night Northumberland Self-Guided Walking Holiday

4-Night Northumberland Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALPOA-4 1, 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a break on the Northumberland Coast with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect self-guided walking holiday. Nether Grange - our historic 4-star country house - is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. It's in a glorious location, just a stone's throw from the beach at Alnmouth, with sea views. Enjoy hearty local food, make use of our detailed walk notes and maps and see what you can discover along Northumberland's wild and wonderful coast. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The use of our Discovery Point to plan your walks – maps and route notes available www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied beauty of Northumberland on foot • Admire sweeping seascapes from the coast of this stunning area of outstanding natural beauty • Head into the Cheviots to discover what makes this area so special, from the solitude of the hills to the clarity of the night sky • Use of our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and detailed walk directions for exploring the local area • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about this stretch of the North East coast's rich history • Evenings in our country house where you share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures • Visit nearby Alnwick Castle • Explore the coast by bike • See the amazing wildlife on the Farne Islands.