A Meta-Criticism of Phyllis Nagy's Reception in London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Patricia Highsmith's Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950S

Patricia Highsmith’s Queer Disruption: Subverting Gay Tragedy in the 1950s By Charlotte Findlay A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2019 ii iii Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………..……………..iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………v Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1: Rejoicing in Evil: Queer Ambiguity and Amorality in The Talented Mr Ripley …………..…14 2: “Don’t Do That in Public”: Finding Space for Lesbians in The Price of Salt…………………44 Conclusion ...…………………………………………………………………………………….80 Works Cited …………..…………………………………………………………………………83 iv Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor, Jane Stafford, for providing always excellent advice, for helping me clarify my ideas by pointing out which bits of my drafts were in fact good, and for making the whole process surprisingly painless. Thanks to Mum and Tony, for keeping me functional for the last few months (I am sure all the salad improved my writing immensely.) And last but not least, thanks to the ladies of 804 for the support, gossip, pad thai, and niche literary humour I doubt anybody else would appreciate. I hope your year has been as good as mine. v Abstract Published in a time when tragedy was pervasive in gay literature, Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt, published later as Carol, was the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. It was unusual for depicting lesbians as sympathetic, ordinary women, whose sexuality did not consign them to a life of misery. The novel criticises how 1950s American society worked to suppress lesbianism and women’s agency. It also refuses to let that suppression succeed by giving its lesbian couple a future together. -

Graduate Celebration

2021 GRADUATE CELEBRATION GRADUATE CELEBRATION PROGRAM Friday, June 11, 2021 CLASS OF 2021 DEPARTMENT OF THEATER MUSICAL PERFORMANCE WHEN I GROW UP, FROM MATILDA THE MUSICAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY TIM MINCHIN PERFORMED BY WALKER BRINSKELE, RIVA BABE BRODY, KIARAH DAVIS, TALIA GLOSTER, JOI MCCOY, CAROLINE PERNICK, HANNAH ROSE, ABE SOANE WELCOME AND RECOGNITION OF MARSHALS BRIAN KITE INTERIM DEAN, UCLA SCHOOL OF THEATER, FILM AND TELEVISION 2021 SPEECHES GENE BLOCK UCLA CHANCELLOR STEVE ANDERSON INTERIM CHAIR, DEPARTMENT OF FILM, TELEVISION AND DIGITAL MEDIA DOMINIC TAYLOR ACTING CHAIR, DEPARTMENT OF THEATER DEMI RENEE KIRKBY VALEDICTORIAN, DEPARTMENT OF THEATER TIFFANY MARGARET ROWSE VALEDICTORIAN, DEPARTMENT OF FILM, TELEVISION AND DIGITAL MEDIA LATIN HONORS RECOGNITION BRIAN KITE KEYNOTE SPEAKER NILO CRUZ PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING PLAYWRIGHT RECOGNITIONS BRIAN KITE CELEBRATION VIDEO UCLA SCHOOL OF THEATER, FILM AND TELEVISION PRESENTATION OF DEGREE CANDIDATES BRIAN KITE FINAL REMARKS UCLA SCHOOL OF THEATER, FILM AND TELEVISION ACKNOWLEDGES THE GABRIELINO/TONGVA PEOPLES AS THE TRADITIONAL LAND CARETAKERS OF THE LOS ANGELES BASIN AND SOUTHERN CHANNEL ISLANDS. AS A LAND GRANT INSTITUTION, UCLA ALSO PAYS RESPECT TO TONGVA ANCESTORS, ELDERS AND RELATIVES - PAST, PRESENT AND EMERGING. LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT MICHAEL V. DRAKE, M.D. Congratulations, UCLA Class of 2021! It is my honor to join your family, friends, and the entire University of California community in celebrating you and your wonderful accomplishment. Amid historically challenging circumstances across the globe, you have worked hard, persisted and persevered, in pursuit of your UC education. I hope you will always take great pride in what you have achieved at the University of California, and in being a part of the UC family for life. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Victor Jenkins CDG., CSA FILM PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR / PRODUCER

Victor Jenkins CDG., CSA FILM PRODUCTION COMPANY DIRECTOR / PRODUCER THE SECRET LIFE OF FLOWERS Bazmark Films Baz Luhrmann (Short) Catherine Knapman/Baz Luhrmann SEE YOU SOON eMotion Entertainment David Mahmoudieh David Stern BROTHERHOOD Unstoppable Entertainment Noel Clarke Jason Maza/Gina Powell ACCESS ALL AREAS Camden Film Co. BrYn Higgins Oliver Veysey/Bill Curbishley AWAY Gateway Films/Slam David Blair Mike Knowles/Louise Delamere NORTHMEN – A VIKING SAGA Elite Film Produktion Claudio Faeh Ralph S. Dietrich/Daniel Hoeltschi INTO THE WOODS (UK Casting Walt Disney Pictures Rob Marshall Consultants) John DeLuca/Marc Platt/ Callum McDougall THE MUPPETS MOST WANTED Walt Disney Pictures James Bobin (UK Casting) Todd Lieberman TOMORROWLAND Walt Disney Pictures Brad Bird (UK Search) Damon Lindelof ANGELICA Pierpoline Films inc Mitchell Lichtenstein Joyce Pierpoline/Richard Lormand IRONCLAD: BATTLE FOR BLOOD Mythic Entertainment Jonathan English Rick Benattar/Andrew Curtis NOT ANOTHER HAPPY ENDING Synchronicity Films John McKaY Claire Mundell BEAUTIFUL CREATURES Alcon Entertainment/Warner Bros. Richard LaGravenese (UK Search) Erwin Stoff / David Valdés STAR TREK 2 (UK Search) Bad Robot/Paramount J.J. Abrams Damon Lindelof KEITH LEMON – THE FILM Generator Entertainment/Lionsgate UK Paul Angunawela Aidan Elliot/Mark Huffam/Simon Bosanquet HIGHWAY TO DHAMPUS Fifty Films Rick McFarland John De Blas Williams ELFIE HOPKINS Size 9/Black & Blue Films Ryan Andrews Michael Wiggs/Jonathan Sothcott Victor Jenkins Casting Ltd T: 020 3457 0506 / M: 07919 -

Kelly Valentine Hendry

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Kelly Valentine Hendry Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 Smyth Address [email protected] Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Director Producer Production Company Amblin/Dreamworks for NBC BRAVE NEW WORLD Owen Harris David Wiener Universal GANGS OF LONDON Gareth Evans Sister Pictures/Pulse Films HBO/Sky Atlantic CITADEL Brian Kirk Sarah Bradshaw AGBO/Amazon Sony Pictures THE WHEEL OF TIME Uta Briesewitz Rafe Judkins Television/Amazon Studios Emma Kingsman- DEADWATER FELL Lynsey Miller Kudos/Channel 4 Lloyd/Diederick Santer COBRA Hans Herbots Joe Donaldson New Pictures for Sky One UNTITLED BRIDGERTON PROJECT Julie Anne Robinson Shondaland Netflix GHOSTS Tom Kingsley Matthew Mulot Monumental Pictures/BBC GOLD DIGGER Vanessa Caswill Mainstreet Pictures BBC1 THE SPY Gideon Raff Legend Films Netflix Brian Kaczynski/Stuart THE CRY Glendyn Ivin Synchronicity Films/BBC1 Menzies Naomi De Pear/Katie THE BISEXUAL Desiree Akhavan Sister Pictures for Hulu and C4 Carpenter HARLOTS Coky Giedroyc Grainne Marmion Monumental Pictures for Hulu Fuqua Films/Entertainment ICE Various Robert Munic One Vertigo Films/Company BULLETPROOF! Nick Love Jon Finn Pictures Robert Connolly/Matthew Hilary Bevan Jones/Tom DEEP STATE Endor/Fox Parkhill Nash BANCROFT John Hayes Phil Collinson Tall Story Pictures/ITV Catherine Oldfield/Francis TRAUMA Marc Evans Tall Story Pictures/ITV Hopkinson/Mike Bartlett RIVIERA Philipp Kadelbach/Various Foz Allen -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

James Strong Director

James Strong Director Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes CRIME Buccaneer/Britbox Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2021 Episodes 1-3. Writer: Irvine Welsh, based on his novel by the same name. Producer: David Blair. Executive producers: Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh, Dougray Scott andTony Wood. VIGIL World Productions / BBC One Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 - 2020 Episodes 1- 3. Starring Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans. Writer: Tom Edge. Executive Producer: Simon Heath. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes LIAR 2 Two Brothers/ ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Episodes 1-3. Writers: Jack and Harry Williams Producer: James Dean Executive Producer: Chris Aird Starring: Joanne Froggatt COUNCIL OF DADS NBC/ Jerry Bruckheimer Pilot Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Television/ Universal TV Inspired by the best-selling memoir of Bruce Feiler. Series ordered by NBC. Writers: Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. Producers: James Oh, Bruce Feiler. Exec Producers: Jerry Bruckheimer, Jonathan Littman, KristieAnne Read, Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. VANITY FAIR Mammoth/Amazon/ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2017 - 2018 Episodes 1,2,3,4,5&7 Starring Olivia Cooke, Simon Russell Beale, Martin Clunes, Frances de la Tour, Suranne Jones. Writer: Gwyneth Hughes. Producer: Julia Stannard. Exec Producers: Gwyneth Hughes, Damien Timmer, Tom Mullens. LIAR ITV/Two Brothers Pictures Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2016 - 2017 Episodes 1 to 3. Writers: Harry and Jack Williams. -

Kelly Valentine Hendry

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Kelly Valentine Hendry Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 Smyth Address [email protected] Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Director Producer Production Company Robert Connolly/Matthew Hilary Bevan Jones/Tom DEEP STATE Endor/Fox Parkhill Nash BANCROFT John Hayes Phil Collinson Tall Story Pictures/ITV Catherine Oldfield/Francis TRAUMA Marc Evans Tall Story Pictures/ITV Hopkinson RIVIERA Philipp Kadelbach/Various Foz Allen Archery Pictures/Sky Atlantic Nigel Marchant/Gareth THE LAST KINGDOM 1-2 Nick Murphy/Various Carnival/BBC/Netflix Neame Ø Kasper Torsting Jean Luc Olivier Studio Plus Patrick Schweitzer/Sally SS-GB Philipp Kadelbach Woodward-Gentle/Lee Sid-Gentle/BBC Morris Richard Stoke/Dan James Strong/Paul BROADCHURCH 1-3 Winch/Jane Kudos/ITV Andrew Williams/Various Featherstone/Chris Chibnall Chris Croucher/Sharon THE HALCYON Various Leftbank/ITV/Sony Hughff Mark Everest/Andy THE LEVEL Jane Dauncey Hillbilly Television/ITV Goddard GRANTCHESTER 1-3 Tim Fywell/Various Emma Kingsman-Lloyd Lovely Day/Kudos/ITV Robert Quinn/Bruce Catherine Oldfield/Francis HOME FIRES 1-2 ITV Studios Goodison/John Hayes Hopkinson/Simon Block Simon Lewis/Catherine TUTANKHAMUN Peter Webber ITV Studios Oldfield/Francis Hopkinson Lynn Horsford/Juliette YOU, ME & THE APOCALYPSE Saul Metzstein/Tim Kirkby Working Title/Sky Howell/Susie Liggatt/Nick Pitt Lydia Hampson/Phoebe Two Brothers FLEABAG Tim Kirkby/Harry Bradbeer Waller-Bridge Pictures/BBC/Amazon -

Michael Keillor Writer/Director

Michael Keillor Writer/Director Michael’s passion for bold and ambitious projects has drawn him to work with a talented mix of writers who share his appetite for pushing boundaries while entertaining audiences. Most recently Michael directed David Hare’s four-part political drama ROADKILL, which captured the world-weary mood of 2020, charting the rise of a corrupt and self-serving politician played with ruthless charisma and impeccable charm by Hugh Laurie. Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes ROADKILL The Forge/PBS/BBC 1 Director and Executive Producer 2020 4-part Drama. Writer: David Hare. Producer: Andy Litvin Exec Producers: George Faber, Mark Pybus, Lucy Richer, David Hare, Michael Keillor. Starring: Hugh Laurie, Helen McCrory, Pippa Bennett Warner, Sarah Greene, Sidse Babett Knudsen, Iain De Caestecker. Popular and charismatic politician Peter Laurence is shamelessly untroubled by guilt or remorse as his public and private life fall apart. *Winner, Original Music Bafta Craft Awards 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes CHIMERICA Playground Director 2018 - 2019 Entertainment/Channel 4 4-part Drama. Writer: Lucy Kirkwood. Producer: Adrian Sturges. Executive Producers: Lucy Kirkwood, Sophie Gardiner, Colin Callender. Starring: Alessandro Nivola and Cherry Jones A photojournalist travels to China with the hopes of finding out who the mysterious man was who was photographed standing defiantly in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square twenty years ago. Adaptation of the Olivier award-winning play. -

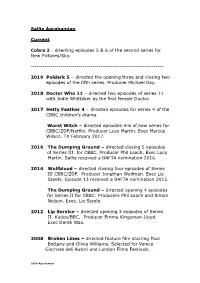

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2 - directing episodes 5 & 6 of the second series for New Pictures/Sky. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2019 Poldark 5 – directed the opening three and closing two episodes of the fifth series. Producer Michael Ray. 2018 Doctor Who 11 – directed two episodes of series 11 with Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor. 2017 Hetty Feather 4 – directed episodes for series 4 of the CBBC children’s drama. Worst Witch – directed episodes 4-6 of new series for CBBC/ZDF/Netflix. Producer Lucy Martin. Exec Marcus Wilson. TX February 2017. 2016 The Dumping Ground – directed closing 5 episodes of Series III for CBBC. Producer Phil Leach. Exec Lucy Martin. Sallie received a BAFTA nomination 2016. 2014 Wolfblood – directed closing four episodes of Series III CBBC/ZDF. Producer Jonathan Wolfman. Exec Lis Steele. Episode 13 received a BAFTA nomination 2015. The Dumping Ground – directed opening 4 episodes for Series II for CBBC. Producers Phil Leach and Simon Nelson. Exec. Lis Steele. 2012 Lip Service – directed opening 3 episodes of Series II. Kudos/BBC. Producer Emma Kingsman-Lloyd. Exec Derek Wax. 2008 Broken Lines – directed feature film starring Paul Bettany and Olivia Williams. Selected for Venice Giornate deli Autori and London Films Festivals. Sallie Aprahamian 2005 – 2009 The Bill – directed 8 episodes of the Thames/ITV series. Producers include Lachlan MacKinnon, Lis Steele and Ciara McIlvenny. 2003 Real Men – 2 x 90’ drama by Frank Deasy. Starring Ben Daniels. Producer David Snodin. Exec Frank Deasy and Barbara McKissack. BBC Scotland/BBC 2. RTS nomination. 2002 Outside the Rules – two part ‘Crime Double’ starring Daniela Nardini for BBC1/BBC Wales. -

Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" As History and Fantasy

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies Winter 2015 Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" as History and Fantasy Patricia White Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Patricia White. (2015). "Sketchy Lesbians: "Carol" as History and Fantasy". Film Quarterly. Volume 69, Issue 2. 8-18. DOI: 10.1525/FQ.2015.69.2.8 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/52 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEATURES SKETCHY LESBIANS: CAROL AS HISTORY AND FANTASY Patricia White Lesbians and Patricia Highsmith fans who savored her 1952 Headlining a film with two women is considered box of- novel The Price of Salt over the years may well have had, like fice bravery in an industry that is only now being called out me, no clue what the title meant. The book’s authorship was for the lack of opportunity women find both in front of and also murky, since Highsmith had used the pseudonym Claire behind the camera. The film’s British producer Liz Karlsen, Morgan. But these equivocations only made the book’s currently head of Women in Film and Television UK, is out- lesbian content more alluring. When published as a pocket- spoken about these inequities. Distributor Harvey Weinstein sized paperback in 1952, the novel sold nearly one million took on the risk in this case, banking on awards capital to copies, according to Highsmith, joining other suggestive counter any lack of blockbuster appeal.