Introduction Myths in Concrete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Brochure/Flyer

FOR LEASE Prime Storefront For Lease Along Broadway Street Just North of Addison Street in Lakeview 3619 North Broadway Street | Chicago, IL 60613 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY OVERVIEW Lease Rate: Negotiable 2,500 SF storefront available for lease at 3619 North Broadway Avenue, just north of the signalized intersection at Addison Street, in Chicago's Lakeview neighborhood. The space NNN's $14.08 PSF benefits from exposure to the signalized intersection featuring over 15,000 VPD and falls Available SF: 2,500 SF withinin a densely populated area with 381,000 residents within a three (3) mile radius. The space presents an opportunity to join a number of national retailers on the immediate stretch of Lot Size: 0.25 Acres Broadway including Jewel-Osco, Fifth/Third Bank, TCF Bank, Starbucks, Walgreen's, and a brand Year Built: 1923 new Planet Fitness directly across the street. The storefront is well located just two (2) blocks west of Lake Shore Drive, five (5) blocks east of the Addison Red Line "L" Station, and six (6) Zoning: B3-2 blocks east of Wrigley Field. From a regional perspective, the storefront is approximately three Market: Chicago (3) miles east of Interstate-90 and directly west of Lake Shore Drive, providing convenient access Submarket: Northwest City to downtown Chicago, the neighboring communities, and the entire interstate system. Other neighboring retailers include Whole Foods, Target, Wal-Mart, Mariano’s, 7-Eleven, IHOP, Forever VPD 6,000 VPD Yogurt, Binny’s Beverage Depot, Crisp, PetSmart, and OrangeTheory, among others. PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS • 2,500 SF storefrontavailable on Broadway, directly across the street from a brand new Planet Fitness • Neighboring retailers include Jewel-Osco, Whole Foods, Target, Wal-Mart, Mariano’s, Planet Fitness, 7-Eleven, IHOP, Starbucks, Forever Yogurt, Binny’s Beverage Depot, PetSmart, OrangeTheory, and TCF Bank. -

739 South Clark Street Chicago, IL

CHICAGO SOUTH LOOP Offering Memorandum For Sale > 30,559 SF (0.70 ACRE) MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT SITE 739 South Clark Street Chicago, IL NORTHNORTH PREPARED BY: Brian Pohl Executive Vice President DIRECT +1 312 612 5931 EMAIL [email protected] Peter Block Executive Vice President DIRECT +1 847 384 2840 EMAIL [email protected] AGENCY DISCLOSURE EXCLUSIVE AGENT Colliers International (“Seller’s Agent”) is the exclusive agent for the owner and seller (“Seller”) of 739 S Clark Avenue (“Property”). Please contact us if you have any questions. No cooperating brokerage commission shall be paid by Colliers or the Seller. Buyer’s Broker, if any, shall seek commission compensation from the Buyer only. DESIGNATED AGENT The designated agents for the Seller are: Brian Pohl Peter Block EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT [email protected] [email protected] DIR +1 312 612 5931 DIR +1 847 384 2840 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Colliers International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information including, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy and reliability. Any interested party should undertake their own inquiries as to the accuracy of the information. Colliers International excludes unequivocally all inferred or implied terms, conditions and warranties arising out of this document and excludes all liability for loss and damages arising there from. This publication is the copyrighted property of Colliers International and/or its licensor(s). ©2015. All rights reserved. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................... -

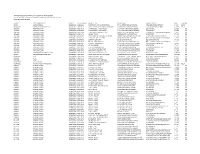

Wisdot Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized Projects and Projects Tentatively Scheduled Through December 31, 2020 Report Date March 30, 2020

WisDOT Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized projects and projects tentatively scheduled through December 31, 2020 Report date March 30, 2020 COUNTY LOCAL MUNICIPALITY PROJECT WISDOT PROJECT PROJECT TITLE PROJECT LIMIT PROJECT CONCEPT HWY SUB_PGM RACINE ABANDONED LLC 39510302401 1030-24-01 N-S FREEWAY - STH 11 INTERCHANGE STH 11 INTERCHANGE & MAINLINE FINAL DESIGN/RECONSTRUCT IH 094 301NS MILWAUKEE AMERICAN TRANSMISSION CO 39510603372 1060-33-72 ZOO IC WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE CONST/BRIDGE REPLACEMENT USH 045 301ZO ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090000 8309-00-00 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020031 DESIGN/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090070 8309-00-70 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020069 CONST/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583510760 8351-07-60 CTH E 400 FEET NORTH JCT CTH C 400FEET N JCT CTH C(SITE WI-16 028) CONS/ER/07-11-2016/EMERGENCY REPAIR CTH E 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201171 8520-11-71 MELLEN - STH 13 FR MELLEN CITY LIMITS TO STH 13 CONST RECST CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201571 8520-15-71 CTH GG MINERAL LK RD-MELLEN CTY LMT MINERAL LAKE RD TO MELLEN CITY LMTS CONST; PVRPLA FY05 SEC117 WI042 CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585300070 8530-00-70 CLAM LAKE - STH 13 CTH GG TOWN MORSE FR 187 TO FR 186 MISC CONSTRUCTION/ER FLOOD DAMAGE CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585400000 8540-00-00 LORETTA - CLAM LAKE SCL TO ELF ROAD/FR 173 DESIGN/RESURFACING CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39587280070 -

Chicago Information Guide [ 5 HOW to USE THIS G UIDE

More than just car insurance. GEICO can insure your motorcycle, ATV, and RV. And the GEICO Insurance Agency can help you fi nd homeowners, renters, boat insurance, and more! ® Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. Homeowners, renters, boat and PWC coverages are written through non-affi liated insurance companies and are secured through the GEICO Insurance Agency, Inc. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Government Employees Insurance Co. • GEICO General Insurance Co. • GEICO Indemnity Co. • GEICO Casualty Co. These companies are subsidiaries of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. GEICO: Washington, DC 20076. GEICO Gecko image © 1999-2010. © 2010 GEICO NEWMARKET SERVICES ublisher of 95 U.S. and 32 International Relocation Guides, NewMarket PServices, Inc., is proud to introduce our online version. Now you may easily access the same information you find in each one of our 127 Relocation Guides at www.NewMarketServices.com. In addition to the content of our 127 professional written City Relocation Guides, the NewMarket Web Site allows us to assist movers in more than 20 countries by encouraging you and your family to share your moving experiences in our NewMarket Web Site Forums. You may share numerous moving tips and information of interest to help others settle into their new location and ease the entire transition process. We invite everyone to visit and add helpful www.NewMarketServices.com information through our many available forums. Share with others your knowledge of your new location or perhaps your former location. If you ever need to research a city for any reason, from considering a move to just checking where somebody you know is staying, this is the site for you. -

Night Game Ordinance 2013

City of Chicago SO2013-7858 Office of the City Clerk Document Tracking Sheet Meeting Date: 10/16/2013 Sponsor(s): Emanuel (Mayor) Type: Ordinance Title: Amendment of Municipal Code Section 4-156-430 regarding athletic contests at night and weekday afternoons Committee(s) Assignment: Committee on License and Consumer Protection 09-013 - 18S% syBSIITUTE ORDINANCE BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF CHICAGO: SECTION 1. Section 4-156-430 of the Municipal Code of Chicago is hereby amended by adding the language underscored and by deleting the language struck through, as follows: 4-156-430 Athletic contests at night and on weekday afternoons Restrictions. (A) (1) It shall be unlav^^ul for any licensee or other person, firm, corporation or other legal entity to produce or present or permit any other person, firm, corporation or other legal entity to produce or present any athletic contest, sport, game, including any baseball game, or any other amusement as defined in Article I of this chapter, if any part of such athletic contest, sport, game, including any baseball game, or any other^ amusement as defined in Article I of this chapter (also known in this section and in this Ordinance as (" Event(6) Event or major league baseball game that takes place between the hours of 8:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m., or is scheduled to begin between the hours of 2:01 p.m. and 4:09 p.m. on weekdays (except for Memorial Day, Independence Day or Labor Day), and is presented in the open air portion of any stadium or playing field which is not totally enclosed and contains more than 15,000 seats where any such seats are located within 500 feet of 100 or more dwelling units. -

Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1996 Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago Costas Spirou Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Spirou, Costas, "Stadium Development and Urban Communities in Chicago" (1996). Dissertations. 3649. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3649 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1996 Costas Spirou LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO STADIUM DEVELOPMENT AND URBAN COMMUNITIES IN CHICAGO VOLUME 1 (CHAPTERS 1 TO 7) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY BY COSTAS S. SPIROU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1997 Copyright by Costas S. Spirou, 1996 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The realization and completion of this project would not have been possible without the contribution of many. Dr. Philip Nyden, as the Director of the Committee provided me with continuous support and encouragement. His guidance, insightful comments and reflections, elevated this work to a higher level. Dr. Talmadge Wright's appreciation of urban social theory proved inspirational. His knowledge and feedback aided the theoretical development of this manuscript. Dr. Larry Bennett of DePaul University contributed by endlessly commenting on earlier drafts of this study. -

MLA '19 Restaurant Guide

MLA ’19 Restaurant Guide Welcome to Chicago! Whether this is your first or fifteenth time in Chicago, there is always some place new to try. We might even go out on a limb and say Chicago has the best selection of restaurants in the world. You choose the type of cuisine, and we’d bet Chicago has a restaurant that will fit the bill. The Restaurant Guide is organized by name, cost, cuisine, and location. For recent reviews and opening hours, we recommend you check out Yelp (www.yelp.com) or TripAdvisor (www.tripadvisor. com). The friendly folks at the Hospitality Booth should also be able to point you in the right direction! For those of you wanting to stick close to the meeting hotel, you can find many estaurantsr in the Loop or Near North side that are walkable. Even more walkable is the Illinois Center, accesible via the Bronze Level of the Hyatt Regency Chicago. You won’t even have to go outside! View an online map of the recommended restaurants here: goo.gl/maps/dX3sML2HTF62. Dietary Needs: We have highlighted a few restaurants in certain categories, but for more comprehensive listings, check out the following: • Gluten-free: chicago.eater.com/maps/best-gluten-free-restaurants-chicago-map • Halal: www.zabihah.com/reg/United-States/Illinois/Chicago/h5AcK9tsfT • Kosher: www.totallyjewishtravel.com/kosherrestaurants-TJ3370-Chicago_Illinois-Kosher_Eater- ies.html • Vegan: foursquare.com/top-places/chicago/best-places-vegan-food • Vegetarian friendly: chicago.eater.com/maps/best-vegetarian-friendly-restaurants-chicago Price Key* • $=(Under $10) • $$=($11–30) • $$$=($31–60) • $$$$=($61+) *Using Yelp price range guidelines. -

Cubs Daily Clips

February 20, 2018 Chicago Sun-Times, Cubs’ Anthony Rizzo back in camp after ‘hardest thing I ever had to do’ https://chicago.suntimes.com/sports/anthony-rizzo-school-shooting-speech-hardest-thing-i-ever- had-to-do/ Chicago Sun-Times, Cubs’ Jon Lester scoffs at allegations brought against agents in lawsuit https://chicago.suntimes.com/sports/cubs-jon-lester-scoffs-at-allegations-brought-against-agents- in-lawsuit/ Daily Herald, Chicago Cubs' Maddon likes the pace http://www.dailyherald.com/sports/20180219/chicago-cubs-maddon-likes-the-pace Daily Herald, Rizzo returns to Chicago Cubs, with heavy heart but ready to go http://www.dailyherald.com/sports/20180219/rizzo-returns-to-chicago-cubs-with-heavy-heart-but- ready-to-go Daily Herald, Rozner: Pace of MLB games not real issue http://www.dailyherald.com/sports/20180219/rozner-pace-of-mlb-games-not-real-issue The Athletic, Two seasons removed from World Series, Cubs again feel like they have something to prove https://theathletic.com/246875/2018/02/20/two-seasons-removed-from-world-series-cubs-again- feel-like-they-have-something-to-prove/ The Athletic, Anthony Rizzo finds escape at Cubs camp after emotionally draining trip to Parkland: 'It was the hardest thing I ever had to do' https://theathletic.com/246813/2018/02/19/anthony-rizzo-finds-escape-at-cubs-camp-after- emotionally-draining-trip-to-parkland-it-was-the-hardest-thing-i-ever-had-to-do/ The Athletic, With a heavy heart, Anthony Rizzo opens up about Parkland shooting https://theathletic.com/246354/2018/02/19/with-a-heavy-heart-anthony-rizzo-opens-up-about- -

Cubs Daily Clips

December 5, 2018 • NBC Sports Chicago, MLB teams pulling out all the stops for Bryce Harper and Cubs reportedly still in the mix https://www.nbcsports.com/chicago/cubs/mlb-teams-pulling-out-all-stops-bryce-harper-and-cubs- reportedly-still-mix-magic-johnson-dodgers-phillies-thome-white-sox • NBC Sports Chicago, State of the Cubs: First base https://www.nbcsports.com/chicago/cubs/state-cubs-first-base-rizzo-bryant-zobrist-baez-injury • NBC Sports Chicago, Even if they don't get Bryce Harper back, the Nationals just ensured they'll be a threat to Cubs, NL in 2019 https://www.nbcsports.com/chicago/cubs/even-if-they-dont-get-bryce-harper-back-nationals-nl- threat-contender-world-series-corbin-strasburg-scherzer • Chicago Tribune, Column: The Cubs have needs to address with winter meetings approaching — and the time is ripe to make roster moves https://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-spt-cubs-moves-20181204-story.html • Chicago Tribune, Alderman says Chicago Cubs ownership looking to take him out of the (political) ballgame https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-met-ricketts-family-44th-ward-20181108- story.html • The Athletic, Are the Cubs lurking in the Bryce Harper sweepstakes? https://theathletic.com/694742/2018/12/04/are-the-cubs-lurking-in-the-bryce-harper- sweepstakes/ -- NBC Sports Chicago MLB teams pulling out all the stops for Bryce Harper and Cubs reportedly still in the mix By Tony Andracki Bryce Harper is still dominating headlines this Hot Stove season and now we're getting a glimpse into the big pitches from each MLB team. -

The 44Th Ward Master Plan Report

BELMONT HARBOR CENTRAL LAKE VIEW EAST LAKE VIEW HAWTHORNE ShEIL PARK SOUThpORT SOUTH EAST LAKE VIEW TRIANGLE WEST LAKE VIEW the 44th ward MASTER PLAN REPORT the 44th Ward MASTER PLAN PRESENTED BY the 44th ward COMMUNITY DIRECTED DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 2006 60 The 44th Ward Master Plan Report DRAFT May 17, 2006 Carol C. Hladik KEY: Blue: Hyperlinks Green: Design/layout notes MASTER PLAN MASTER PLAN the 44th Ward <#>12 TABLE OF CONTENTS section page 1 Alderman’s Letter 2 2 The Planning Process 3 3 The History of Lake View* 1837-2006 4 4 Lake View Today 6 5 Residential 18 6 Affordable Housing 24 7 Business 28 8 Service Organizations 36 9 Transportation and Parking 40 10 Parks and Open Spaces 48 * Historically, the area was called “Lake View,” but current usage also includes “Lakeview.” the 44th Ward MASTER PLAN MASTER PLAN 601 alderman TOM TUNNEY I want to thank the 44th Ward Community Directed Development Council members for their hard work in producing this report. Dozens of community leaders volunteered countless hours to this project, which stands as an example of what can be accomplished when all segments of the community come together to talk about their vision for their neighborhood, and work to make that vision a reality. I especially want to thank the CDDC Master Plan Task Force for going the extra mile and getting us to the finish line. They include: • Ben Allen, Northalsted Area Merchants Association • Norman Groetzinger, Counseling Center of Lake View • Susan Hagan, East Lake View Neighbors • Chester Kropidlowski, Lake View Citizens’ Council • Alicia Obando, 44th Ward Chief of Staff • Marie Poppy, Central Lake View Neighbors • Jim Schuman, Central Lakeview Merchants Association I hope that this Master Plan becomes a productive tool for all who live, work and visit in the 44th Ward to help ensure that we keep our community the vibrant, desirable place that it has become. -

Wrigleyville Remixed the Neighborhood Around the Home of the Chicago Cubs Is Getting a Serious — and Sophisticated — Makeover See WRIGLEY, Page 36

Wrigleyville remixed The neighborhood around the home of the Chicago Cubs is getting a serious — and sophisticated — makeover See WRIGLEY, Page 36 Magic moment: The Chicago Cubs buried decades of frustration in 2016 by winning the World Series over the Cleveland Indians. Above, the sign outside Wrigley Field before Game 5 on Oct. 30, the last World Series game played at Wrigley. The fnal two games of the Series were in Cleveland. JERRY LAI, USA TODAY SPORTS USA TODAY SPECIAL EDITION 35 Matt Alderton | Special to USA TODAY Chicagoans aren’t generally the sort of people who believe in fairy tales. A mélange of political corruption, harsh weather, and sensational crime — from the Mob days of Al Capone to 21st-century gun violence “The baseball season is only — has left a cynical taste in their mouths. And yet, Chicago is a living, fve to six months a year. The breathing Cinderella story. ❚ Just look at the city’s beloved “Cubbies.” new additions coming into According to local lore, the Chicago the community are Cubs lost the World Series in 1945 when an aggrieved fan placed a curse on them. making Clark Street much For more than 70 years thereafter, the more vibrant and much more Cubs failed and foundered. Then, on Nov. 2, 2016, their fortunes fnally approachable for people changed with a jubilant World Series vic- other than baseball fans.” tory over the Cleveland Indians, whom they bested in a stunning 10-inning Richard Levy, area resident Game 7. It was the fairy-tale ending Chi- cago never trusted but always deserved. -

The Chicago Cubs and Wrigley Field Account for $638 Million Annually In

The Restoration of Wrigley Field As we consider the most extensive renovation of Wrigley Field in history, it is critical we, as neighbors, discuss the impact the Cubs have on the community and whether our need to remain competitive on the field can be met in the amazing community we share. The following outlines the proposed terms by the Chicago Cubs as the organization considers the most extensive renovation of Wrigley Field in history. The framework contains many elements and addresses key areas including: community investment, parking, public safety, amenities, the ballpark operations and scheduling. If approved, this $500 million in new investment to Wrigley Field and the surrounding areas will create 2,100 new jobs and generate hundreds of millions in new tax revenue for the city, state and county. It would be among the biggest investments currently underway in Chicago. The Cubs and the Ricketts family are also committed to be good neighbors and the proposal demonstrates this commitment and is consistent with our on-going community involvement. The Restoration plan includes the following: Community Benefits • A $1 million commitment to fund a new park and playlot at 1230 W. School. • $3.75 million donated by Cubs for community infrastructure and amenities agreed jointly by Cubs and Alderman ($500,000 per year from 2014-2018; $250,000 per year from 2019-2023). • A $500 million investment to create jobs, improve our community appearance, enhance the neighborhood and upgrade undeveloped, underutilized and unattractive existing space. • An open-air plaza outside the ballpark with ability to continue hosting an ice rink in the winter and add farmers markets in the summer, free family activities and other community events.