Milltownpassed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leinster Results Archive – 2000-2018 Table of Contents

LEINSTER RESULTS AR CHIVE – 2000-2018 1 LEINSTER RESULTS ARCHIVE – 2000-2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LEINSTER COUNCIL CHAIRMEN .. .. .. .. 4 LEINSTER COUNCIL SECRETARIES .. .. .. .. 4 HURLING Leinster Senior Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 4-5 Leinster Intermediate Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 5 Leinster U-21 Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 6 Leinster Minor Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 6-7 Leinster Minor Hurling League Final Results .. .. .. .. 7 Leinster Club Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 7-8 Walsh Cup S.H. Final Results .. .. .. .. 8-9 Walsh Cup S.H. Shield Final Results .. .. .. .. 9 Kehoe Cup S.H. Final Results .. .. .. .. 9-10 Kehoe Cup S.H. Shield Final Results .. .. .. .. 10 Leinster Junior Hurling Shield Final Results .. .. .. .. 10-11 Leinster Club Intermediate Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 11 Leinster Club Junior Hurling Final Results .. .. .. .. 11 Leinster Club Junior Hurling Special Final Results .. .. .. .. 12 Leinster Senior Hurling Finalists .. .. .. .. 12-18 Leinster Interprovincial Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 18-20 Leinster All Ireland Senior Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 20-22 Leinster U-21 All Ireland Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 22-23 Leinster Minor All Ireland Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 23-24 Leinster All Ireland Intermediate Hurling Winning Teams .. .. .. 24-25 Leinster National League Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 25-26 Leinster Club All Ireland Winning Hurling Teams .. .. .. .. 26-27 Leinster Christy Ring Cup Final Winning Teams .. .. .. .. 27-28 Leinster Club Intermediate All Ireland Winning Hurling Team .. .. .. 28 Leinster Club Junior All Ireland Winning Hurling Team .. .. .. .. 28 Leinster All Star Hurlers .. .. .. .. 28-29 Leinster Texaco Hurling Award Winners .. .. .. .. 30 Leinster Senior Hurling County Champions .. .. .. .. 30-32 2 FOOTBALL Leinster Senior Football Final Results .. .. .. .. 33 Leinster Junior Football Final Results .. .. .. .. 33-34 Leinster U-21 Football Final Results . -

LMETB Land and Buildings Insight

LAND AND BUILDINGS INSIGHT Foreword I am pleased to present an insight into the activity of LMETB’s Land and Buildings The Board of LMETB has played a crucial role in I want to bring your attention to a very innovative Department. With increased enrolments, successful patronage campaigns for supporting the collective achievements of LMETB development occurring in LMETB, namely our and I would like to acknowledge its contribution, in new Advanced Manufacturing Training Centre of new schools and rapidly expanding Further Education and Training provision, particular the members of the Land and Buildings Excellence in Dundalk which was the brainchild of there has been a significant expansion of associated capital projects over the Sub-Committee. The membership of the Land our Chief Executive. More on that later…!! past number of years. This overview will give the reader an appreciation of the and Buildings Sub-Committee comprises Mr. Bill Sweeney (Chair), Cllr. Sharon Tolan, Cllr. Nick The Land and Buildings Department has many projects currently being delivered by the Land and Buildings Team and a Killian, Cllr. Maria Murphy, Cllr, John Sheridan and established and maintained excellent working preview of what is planned for 2021. These are exciting times for LMETB as we Cllr. Antoin Watters. LMETB has made governance relationships with key stakeholders. This, coupled commence a whole host of new projects across Louth and Meath. a key priority and our Land and Buildings Sub- with LMETBs vision and experience allows us Committee is tasked with very detailed “Terms deliver state of the art capital projects within of Reference”. -

Longford Westmeath CSC Children and Young People's Plan 2011-2013

Page 1 of 57 - 1 - Longford Westmeath Children’s Services Committee Children and Young People’s Plan 2011 - 2013 Children and Young People’s Plan Longford Westmeath Page 2 of 57 - 2 - Contact Suggested text: “The Longford Westmeath Children’s Services Committee welcomes comments, views and opinions about our Children and Young People’s Plan. Please contact: Child Care Manager’s Office, Health Centre, Longford Road, Mullingar, Co. Westmeath Tel: 044 939501920 Copies of this plan are available on: www.westmeathcoco.ie and www.longfordcoco.ie Children and Young People’s Plan Longford Westmeath Page 3 of 57 - 3 - Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 5 Background to the CSC initiative and policy context .............................................................. 6 Who we are ................................................................................................................................... 7 Achievements to date .................................................................................................................. 8 How the Children and Young People’s Plan was developed ..............................................10 Section 2: Socio-Demographic Profile of Insert County ....................................................... 12 Section 3: Overview of Services to Children and -

Mullingar 2021 FINAL

Mullingar Calendar 2021 Your Collection Day Bank Holiday Collections falling on a Monday are collected on the previous Saturday JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 APRIL MAY JUNE M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 31 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 1 27 28 29 30 OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 27 28 29 30 Managing Your Waste for a Greener Future! MULLINGAR COLLECTION DAYS If your route is not on the list below please check the Athlone Calendar MONDAY Ardmore Rd. -

Midlands Arts and Culture Magazine Autumn-Winter 2016

Midlands andCulture ArtsMagazine A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH AUTUMN/WINTER 2016 • ISSUE 26 Celebrating of Midland Arts THE WRITTEN WORD MUSIC & DANCE THEATRE & FILM VISUAL ARTS FREE MidlandsArts andCultureMagazine Contents • 10th anniversary ..............................Page 2 LS 17 Studios Gary Dunne • Siege of Jadotville.......................Page 3 Longford schools of photography........................Page 4 Origami wonderland Leaves Lit Festival • Army Band .........................Page 5 Then & Now Eva Burke • Tomás Skelly..............Page 6 The Art of Blogging...............................................Page 7 A Word from High Achiever Awards • Top of the Rock ............Page 8 the Editor Pat Boran – When it comes to making art .........Page 9 This year has been a remarkable one in so many ways – there were the 1916 Street Theatre • I’m Your Vinyl .........................Page 10 commemorations and I use that word Abbey Road Artists............................................Page 11 deliberately, rather than celebrations, because Sink: Sync: Surface............................................Page 12 so many facets of that troubled time were 4 Degrees West • Orange Door........................Page 13 horrific. Halloween Howls • Dáire O’Muiri .....................Page 14 The purpose of art is to shine a light on all Archaeology of Cinema......................................Page 15 aspects of life. Culture, like history is not simply black and white. There are many Emerging Artist • Music Network.....................Page -

Seanad Electoral Roll 2002

Number 51A 1 Supplement Published by Authority TUESDAY, 25th JUNE, 2002 This publication is registered for transmission by Inland Post as a newspaper. The postage rate to places within Ireland (32 counties), places in Britain and other places the printed paper rate by weight applies. SEANAD ELECTORAL (PANEL MEMBERS) ACTS, 1947 AND 1954 ELECTORAL ROLL The Electoral Roll prepared by the Seanad Returning Officer under section 45 of the Seanad Electoral (Panel Members) Act, 1947, as amended by the Seanad Electoral (Panel Members) Act, 1954, of persons entitled under section 44 of the Act of 1947 to vote at the election of panel members at the Seanad General Election consequent on the dissolution of Da´il E´ ireann by the Proclamation of the President of the 25th day of April, 2002. Under the heading ‘‘Description’’ the Letter D denotes ‘‘a member of Da´il E´ ireann’’. ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, S ,, ‘‘a member of Seanad E´ ireann’’. ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, L ,, ‘‘a member of the council of a county or county borough (city council)’’. ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, A ,, ‘‘a member of the council of a county borough (city council) who is an alderman’’. Uimh. Ainm Tuairisc Seoladh No. Name Description Address 1 Abbey, Michael ...................... L. 32 Green Road, Carlow. 2 Adams, Margaret ................... L. King’s Hill, Wesport, Co. Mayo. 3 Ahern, Bertie.......................... D. St. Lukes, 161 Lower Drumcondra Road, Dublin 9. 4 Ahern, Dermot....................... D. The Crescent, Blackrock, Co. Louth. 5 Ahern, Maurice ...................... A. Members Room, City Hall, Cork Hill, Dublin 2. 6 Ahern, Maurice ...................... L. Carrigogna, Midleton, Co. Cork. 7 Ahern, Michael....................... D. ‘‘Libermann’’, Barryscourt, Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork. 8 Ahern, Michael...................... -

Public Participation Network the Voice of the Community

What is the aim of Westmeath PPN Westmeath PPN? Our aim is to support Public community groups & co-ordinate how the community in Westmeath Participation is represented. We also aim to: Network Make our members stronger: and keep our members informed about local developments What does Westmeath The Voice of the Community PPN do? VOLUME 2 ISSUE 6 J U N E 2 0 1 9 We empower our member groups to influence policy makers. Westmeath PPN has started the process of creating a Westmeath Vision for Community Wellbeing What’s in this Developing a Vision for Community Wellbeing means thinking about what we have and what Month’s Issue we need to help Westmeath to be the best that it can be for us and for the many generations that Call for Expressions of 2 follow on from ours. Interest - National Walks Scheme Our well being is affected by many things; the economy, the environment, services etc and the wellbeing of the community affects everyone within it. All this information will be brought Cruinniú na nÓg 2019 3 together and be used to influence policy and guide the work of the PPN and its representatives Community Wellbeing in influencing policy and working towards achieving the community’s goals. Vision for Westmeath 4 Wellbeing is an increasingly common term that can describe wider conditions than good physi- 2019 Town and Village 6 Renewal Scheme cal and mental health, which we need as individual and communities to have a better quality of Announced life, a healthier environment and increased prosperity. Some of these are things that we can Community Wellbeing the easily measure, like the number of pre-school places, or the speed with which an ambulance 7 six heading explained can get to a sick person. -

Eirgrid Sponsorships 2016 Sponsored Group

EirGrid Sponsorships 2016 Sponsored Group 9th Westmeath Milltownpass Scout Group Ardclough Community Centre Ashbourne United A.F.C. Ballinabrackey GAA underage Ballinteer St John's GAA Club Book Trust NI Border Bowlers Unlimited Brackloon National School Cairdeas Community Childcare Centre Cancer Research UK Carrick on Shannon Carnival Carrickmacross Emmets GAA CoderDojo Dun Laoghaire CoderDojo Mullingar Coralstown Action Group Coralstown Kinnegad GAA Coralstown National School Parents Council Crossmolina National School Cullion Amenity Development Group Curraghmore National School Parents Association Dalton Community Childcare Dalton Park Womens Group Donaghadee Rugby Club Dublin and Wicklow Mountain Rescue Team Dunboyne Athletic Club ElectricAid Grange Community Group / Grange Community Childcare Grange Women's Group Hay Festival Kells Jordan Junior Youth Club Kilinkere Parish Committee Kinnegad Juniors AFC Knockmuldowney Residents Association Lake County Beekeepers Lakeside Wheelers Mullingar Lucan Sarsfields GAA club Milltownpass GAA Milltownpass Ladies Football Club Milltownpass Senior Citizens Social Fund Milltownpass Social Morning Group (Active Elderly) MRC Community Arts & Crafts Group Mullingar Harriers Athletic Club Mullingar Jets Swimming Club Mullingar Men's Shed Mullingar Royal Canal Community Group Mullingar Town Band Mullingar Youth and Community Project Naomh Padraig an Goirtin, GAA Club National Adult Literacy Agency O'Dwyer GAA Club, Balbriggan Olympic Boxing Club Mullingar Order of Malta Ambulance Corps Our Lady's Hospice & Care Services RNLI Round Towers Lusk GAA Club Science & Technology in Action St Oliver Plunkett's Hurling Club St Sylvester's GAA Club Temporary Emergency Accommodation Midlands The Downs Community Group Thomastown Royal Canal Communities Group Westmeath Community Development Westmeath LGFA Youth Work Ireland Midlands Sponsorship Total: €420,990 . -

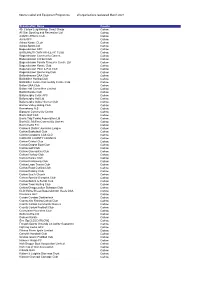

Grid Export Data

Sports Capital and Equipment Programme all organisations registered March 2021 Organisation Name County 4th Carlow Leighlinbrige Scout Group Carlow All Star Sporting and Recreation Ltd Carlow Ardattin Athletic Club Carlow Asca GFC Carlow Askea Karate CLub Carlow Askea Sports Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown AFC Carlow BAGENALSTOWN ATHLETIC CLUB Carlow Bagenalstown Community Games Carlow Bagenalstown Cricket Club Carlow Bagenalstown Family Resource Centre Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown Karate Club Carlow Bagenalstown Pitch & Putt Club Carlow Bagenalstown Swimming Club Carlow Ballinabranna GAA Club Carlow Ballinkillen Hurling Club Carlow Ballinkillen Lorum Community Centre Club Carlow Ballon GAA Club Carlow Ballon Hall Committee Limited Carlow Ballon Karate Club Carlow Ballymurphy Celtic AFC Carlow Ballymurphy Hall Ltd Carlow Ballymurphy Indoor Soccer Club Carlow Barrow Valley Riding Club Carlow Bennekerry N.S Carlow Bigstone Community Centre Carlow Borris Golf Club Carlow Borris Tidy Towns Association Ltd Carlow Borris/St. Mullins Community Games Carlow Burrin Celtic F.C. Carlow Carlow & District Juveniles League Carlow Carlow Basketball Club Carlow Carlow Carsports Club CLG Carlow CARLOW COUNTY COUNCIL Carlow Carlow Cricket Club Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club Carlow Carlow Golf Club Carlow Carlow Gymnastics Club Carlow Carlow Hockey Club Carlow Carlow Karate Club Carlow Carlow Kickboxing Club Carlow Carlow Lawn Tennis Club Carlow Carlow Road Cycling Club Carlow Carlow Rowing Club Carlow Carlow Scot's Church Carlow Carlow Special Olympics Club Carlow Carlow -

County by County Breakdown 2021.Xlsx

Intel Matching Grant Organisations – 2021 ORGANISATION COUNTY St Patricks Gaelic Athletic Club, Dromintee Armagh Clonegal National School Carlow County Carlow Football Club Carlow Gaelscoile Eoghain Ui Thuairisc Carlow Killeshin FC Carlow Palatine GAA Club Carlow Rathvilly Juvenile GAA Club Carlow Scoil Mhuire gan Smal Carlow Setanta GAA Ceatharlach Carlow Slaney Rovers AFC Carlow St Patrick's National School Carlow Tullow RFC Carlow Ballyhaise GAA Club Cavan Castletara N.S. Cavan Kill National School Cavan Kill Shamrocks GAA Cavan Munterconnaught Gaelic Football Club Cavan Banner GAA Club Clare Barefield National School Clare Fergus Rovers Ladies Football Club Clare Scariff Central NS Clare Scariff GAA Club Clare St Joseph's Doora Barefield GAA Club Clare Bishopstown GAA Club Cork Cork Samaritans Cork Douglas Hall AFC Cork Feileacain Teoranta Cork Irish Guide Dogs for the Blind Cork Rockban Ladies Football - Camogie Club Cork Robert Emmets GAA club Donegal Sn Naomh Samhthann Donegal 11th Meath Kilcloon Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 1st 10th Kildare Leixlip Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 1st Kildare, 2nd Celbridge Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 20th Meath (Stamullen) via Scouting Ireland Dublin 22nd Kildare Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 24th Kildare Carbury Scout Group via Scouting Ireland Dublin 8th Kildare Scout Group (Maynooth) via Scouting Ireland Dublin ALONE Dublin Amnesty International Ireland Dublin An Taisce-National Trust For Ireland. Dublin Aoibheanns Pink Tie Dublin Ashbourne United Football -

115 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

115 bus time schedule & line map 115 UCD Belƒeld Campus stop 135061 - Mullingar View In Website Mode Station stop 135781 The 115 bus line (UCD Belƒeld Campus stop 135061 - Mullingar Station stop 135781) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dublin (Belƒeld) - Outside Train Station: 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM (2) Outside Train Station - Dublin (Belƒeld): 5:50 AM - 11:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 115 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 115 bus arriving. Direction: Dublin (Belƒeld) - Outside Train Station 115 bus Time Schedule 23 stops Dublin (Belƒeld) - Outside Train Station Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Connolly Station Stop 135121 Monday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM 1 Amiens Street, Dublin Tuesday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Dublin Halfpenny Bridge 4 Temple Bar, Dublin Wednesday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Dublin (Opp. Heuston Station) Thursday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Friday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Liffey Valley (Lucan Road) Saturday 1:00 AM - 11:30 PM Lucan Spa Hotel Stop 134461 Glenroyal Hotel Stop 135461 Maynooth University Stop 103161 115 bus Info Direction: Dublin (Belƒeld) - Outside Train Station Kilcock Stop 134031 Stops: 23 The Harbour, Kilcock Trip Duration: 97 min Line Summary: Connolly Station Stop 135121, Kilcock Stop 5115 Dublin Halfpenny Bridge, Dublin (Opp. Heuston Esso Forecourt, Kilcock Station), Liffey Valley (Lucan Road), Lucan Spa Hotel Stop 134461, Glenroyal Hotel Stop 135461, Kelleghers Cross Stop 133731 Maynooth University Stop 103161, Kilcock Stop 134031, Kilcock Stop -

Inspector's Report ABP-305992-19

Inspector’s Report ABP-305992-19 Development 10 year permission for the construction of a Solar PV Energy and all associated site development works. Location Clonfad, Enniscoffey or Caran, Hightown or Ballyoughter, Lowtown or Balleighter, Pass of Kilbride and Rattin, Co.Westmeath. Planning Authority Westmeath County Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 196168 Applicants JBM Solar Developments Limited Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Grant Permission Type of Appeal Third Party against permission First Party against condition Appellants Sharon Griffith Geraldine McDermott & others JBM Solar Developments Limited Observers Christopher Brennan Rachel & Henrietta Leech Date of Site Inspection 8th June 2020 Inspector Dolores McCague ABP-305992-19 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 100 Contents 1.0 Site Location and Description ......................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Proposed Development ................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Planning Authority Decision .......................................................................................................... 35 Decision ................................................................................................................................. 35 Planning Authority Reports ................................................................................................... 43 Prescribed Bodies ................................................................................................................