Reading Fluency and Students with Reading Disabilities: How Fast Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Fluency? Adapted From: Elish-Piper, L

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY | JERRY L. JOHNS LITERACY CLINIC Raising Readers: Tips for Parents What is Fluency? Adapted from: Elish-Piper, L. (2010). Information and ideas for parents about fluency and vocabulary.Illinois Reading Council Journal, 38(2), 48-49. Reading fluency is the ability to read a text easily. Reading mean that children should read as fast as they possibly can. fluency actually has four parts: accuracy, speed, expression and Rate needs to be combined with accuracy, expression and comprehension. Each part is important, but no single part is comprehension to produce fluent reading. Some schools enough on its own. A fluent reader is able to coordinate all four provide a target rate for students in each grade level, usually as aspects of fluency. the number of correct words read per minute. You may wish to ask your child’s teacher if there is a rate goal used for your Accuracy: Reading words correctly is a key to developing fluency. Children need to be able to read words easily without child’s grade level. Those rate targets are important, but they having to stop and decode them by sounding them out or are not the only goal for fluency. For example, if a child reads breaking them into chunks. When children can accurately and very quickly but does not read with expression or understand easily read the words in a text, they are able to think about what what is read, that child is not reading fluently. they are reading rather than putting all of their effort toward Expression: Expression in fluency refers to the ability to read figuring out the words. -

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction Augustine Literacy Project - Charlotte Marion Idol, Site Coordinator Five Essential Components of Reading Instruction: 1.phonemic awareness 2.phonics 3.fluency 4.vocabulary 5.comprehension http://athome.readinghorizons.com/ Importance of Decoding skills: In many schools, 1st and 2nd grade instruction focuses on FVC instead of PA and P.(decoding) For our students, the holes in the foundation tend to be in PA and P. Please prioritize setting a firm foundation! For 1st month of tutoring, don’t worry about weaving in FVC instruction. Fluency/Vocabulary/Comprehension Instruction: What does it look like for 1st/2nd graders? How do I weave this instruction into each lesson? What are fun supplemental activities for “TAKE a BREAK” sessions? Fluency: ALP Manual: Tab 5, pp. 174-178 The ability to read text accurately and quickly. Scored as words read correctly per minute. ONLY DECODABLE TEXT! Easy independent reading level (95% success) Requires repeated ORAL reading practice with a partner providing modeling, feedback, and assistance Includes PROSODY: appropriate expression, inflection, pacing Activities to Promote Fluency Each session: You will already be doing repeated oral reading practice in lesson parts 3-5, 9 To add fun and prosody practice, when student rereads sentences in part 5, play “Roll Punctuation” or “Roll a Face.” Parts 3-5, 9. Handout B. Fluency “Take a Break” session activities: Paired Reading: Reading aloud along with your student to promote correct pacing, inflection, expression https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5RJyUnAkWM Punctuation Punch: Periods, commas, question marks, exclamation point. Fun AVK stimulation! Use book Yo! Yes! to teach this technique. -

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language Academic Areas of Concern Students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) have severe trouble learning or demonstrating skills in one or more of these academic areas: oral expression reading fluency listening comprehension reading comprehension written expression mathematics calculation and basic reading skill mathematics problem solving Students with SLD often do well in some school subjects but have extreme difficulty with skills like decoding (sounding out) words, calculating math facts, or writing down their thoughts. Even with adequate instruction and intensive intervention, a student with SLD has low classroom achievement when compared to students without disabilities in the same grade. Specific information about how the student has responded to instruction and intensive intervention is used to decide if a student is SLD or if the student is not achieving for other reasons. Referral for Special Education When someone thinks a student might have any disability and needs special education, a referral for a special education evaluation is made to the school. The referral must be in writing and say why the person making the referral thinks the student has a disability. A group of people, called an IEP team, which includes the student’s parents, does an evaluation and decides if the student meets state and federal criteria. Three Criteria to Meet The three criteria (requirements) below must be considered by the IEP team and all 3 of them must be met in order to decide the student has SLD. 1. Inadequate Classroom Achievement - This means a student's academic skills in one or more academic areas of concern are well outside the expected range for students without disabilities of the same age. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

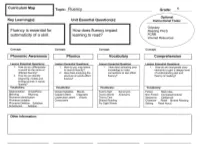

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

The Relationship Between Fluency and Comprehension

The Relationship between Fluency and Comprehension By Tania Myers Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education July 2015 Graduate Programs in Education Goucher College Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of Problem 2 Hypothesis 2 Operational Definitions 2 II. Review of the Literature 4 Defining Fluency and Comprehension 5 Relationship between Fluency and Comprehension 8 Boosting Reading Fluency and Comprehension in the Classroom 9 Progress Monitoring Fluency and Comprehension 14 Summary 18 III. Methods 19 Design 19 Participants 19 Instruments 20 Procedure 20 IV. Results 22 V. Discussion 24 Implications of Results 25 Threats to Validity and Reliability 26 Connections to Previous Studies 28 Recommendations for Future Research 29 References 32 List of Tables 1. Means and Standard Deviations of DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency and MAP Reading 22 Scores 2. Pearson Correlation between DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency and MAP Reading 22 Scores During Each Test Interval (Fall, Winter, and Spring) i Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between reading fluency and comprehension and whether a student’s fluency rate impacted his or her ability to comprehend information. The study looked closely at the performance of 23 students enrolled in a second grade class. The measurement tools used were the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, Sixth Edition (DIBELS), Oral Reading Fluency Assessment, and the Measures of Academic Progress Reading Assessment. The study involved the use of data collected during fall, spring, and winter testing intervals from the 2014-2015 school year. -

The Importance of Phonics: Securing Confident Reading

The Importance of Phonics: Securing Confident Reading 1. Literacy levels in England: what’s happening now? After seven years of primary education, one in six 11 year olds still struggles to read. The 2011 tests for children leaving primary school also reveal that one in 10 boys aged 11 read no better than a seven year old. The PISA 2009 Study ‘How Big is the Gap?’ highlights how far England has slipped behind other nations in reading. GCSE pupils' reading is more than a year behind the standard of their peers in Shanghai, Korea and Finland. Overall, in the last nine years, England has fallen in PISA’s international tables from 7th to 25th in reading. This decline is reflected in the skills of England’s workforce. Employers report that young entrants to the labour market often lack the basic literacy skills to work effectively. The absence of these valued skills appears to have a direct impact on the high levels of youth unemployment. The Centre for Cities policy institute reports “youth unemployment in cities correlates to GCSE attainment. Those cities with high youth unemployment characteristically have significantly lower attainment in GCSE Maths and English.” (2011). Those who achieve a good start in the first few years of reading are very likely to have accelerated progress in their attainment throughout school and achieve the skills valued by employers. Of the children who achieved the high level 2a in Key Stage 1 reading, 98% went on to achieve the expected level 4 or above in Key Stage 2 in 2010 and 66% achieved level 5. -

Elements of a Reading Workshop to Increase Stamina, Fluency, & Joy

Elements of a Reading Workshop to increase Stamina, Fluency, & Joy Time Students need time to read in class in order to create a habit of reading and set the stage for homework reading, and teachers need reading time to confer individually with students about their choices, stamina, engagement, and goals. Students need time to discuss choices with classmates, time to analyze their progress, and time to practice fluency & comprehension strategies under the direction of the teacher. Choice Students need to make choices in reading that reflect their interests because interest drives engagement. Teachers should encourage wide reading in all genres as well as students who pursue an author or genre study. Allow students to reread favorite books and to abandon a book that no longer interests them. Response Teacher conferences are the primary tool for assessing progress, encouraging goal- setting and reflection, and analyzing student needs. Students will reflect on reading in writing (themed notebooks & writers’ notebooks), facilitate discussions in small groups, join blogs or reading sites for discussions outside of class, and respond regularly to other readers in the room. Vision Daily book talks present a wide range of voices, styles of text, categories of interest, etc. and are essential for helping students develop their own ‘to read next’ lists. We must commit to helping students define themselves as readers who like… Expectations All readers will develop the stamina to read longer and with greater fluency with daily practice. A reading rate is calculated regularly and students are expected to meet a weekly goal based on the challenge of the current selected text. -

The Incorporation of Words Their Way Word Sorts Into Orton-Gillingham Method to Improve Fluency of Students with Learning Disabi

Cardinal Stritch University Stritch Shares Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects 10-28-2014 The ncorI poration of Words Their aW y Word Sorts into Orton-Gillingham Method to Improve Fluency of Students with Learning Disabilities Katie A. Tyk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Tyk, Katie A., "The ncI orporation of Words Their aW y Word Sorts into Orton-Gillingham Method to Improve Fluency of Students with Learning Disabilities" (2014). Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 370. https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd/370 This Action Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Stritch Shares. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Stritch Shares. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Incorporation of Words Their Way Word Sorts into Orton-Gillingham Method to Improve Fluency of Students with Learning Disabilities By Katie A. Tyk Action Research Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Special Education At Cardinal Stritch University Milwaukee, Wisconsin 2014 2 This action research has been approved for Cardinal Stritch University by October, 2014 _________________________ Date _________________________ 3 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I would like to thank my husband for the support and patience. I am forever grateful for the countless hours he gave me to write in peace and the time he spend looking over the many pages of writing when he didn’t have to. Thank you to my little peanut who reminded me that there is always time for brain breaks. -

How to Write Goals Dr. Kelli Sandman-Hurley Dyslexia Training Institute

Dyslexia: How to Write Goals Dr. Kelli Sandman-Hurley Dyslexia Training Institute I am noticing a disturbing trend when I read IEPs and I have had some nonsensical conversations about reading with IEP teams lately as well. This trend and these conversations center around the goals section of the IEP. What this has revealed to me is what I have suspected all along – there is a lack of expertise and understanding of not only dyslexia, but the progression of teaching reading and the components of the reading process. To correct this trend I offer the following examples to illustrate some fallacies about reading as well as how to fix goals. Parents have asked me, how important are the goals anyway? Remember: needs drive goals and goals drive services. The school is only held responsible for the goals that are set and agreed upon in the IEP. If they are low or incorrect and the IEP is signed, the school is only responsible for those goals. It seems to make more sense to make sure the goals are written so that the child receives some educational benefit and that the goals make pedagogical sense. For example, if there is a need for fluency improvement then there should be a goal for that. Is there is a need for spelling, there should be a goal for that. If there is a need for sight word improvement, then there should be a goal for that. If there are ten needs, then there are ten goals. There is no limit to the number of goals an IEP can have. -

Beyond Fluency: Deepening Knowledge About What Students Know Grades K – 5

Beyond Fluency: Deepening Knowledge About What Students Know Grades K – 5 http://ccss.tcoe.org/ Christine Roberts Marla Olson [email protected] [email protected] @tcoechristine Developing and Assessing Fact Fluency, K – 6 What is math fact fluency? Initial Definition Revised Definition Mastering Basic Facts Phase 1 – Phase 2 – Phase 3 – CMC-S p. 1 Fluency Standards in Grades K - 6 Grade Fluency Standard K K.OA.5 Fluently add and subtract within 5. 1 1.OA.6 Add and subtract within 20, demonstrating fluency for addition and subtraction within 10. Use strategies such as counting on; making ten (e.g., 8 + 6 = 8 + 2 + 4 = 10 + 4 = 14); decomposing a number leading to a ten (e.g., 13 – 4 = 13 – 3 – 1 = 10 – 1 = 9); using the relationship between addition and subtraction (e.g., knowing that 8 + 4 = 12, one knows 12 – 8 = 4); and creating equivalent but easier or known sums (e.g., adding 6 + 7 by creating the known equivalent 6 + 6 + 1 = 12 + 1 = 13). 2 2.OA.2 Fluently add and subtract within 20 using mental strategies.2 By end of Grade 2, know from memory all sums of two one-digit numbers. (Footnote: 2. See standard 1.OA.6 for a list of mental strategies.) 2.NBT.5 Fluently add and subtract within 100 using strategies based on place value, properties of operations, and/or the relationship between addition and subtraction. 3 3.OA.7 Fluently multiply and divide within 100, using strategies such as the relationship between multiplication and division (e.g., knowing that 8 × 5 = 40, one knows 40 ÷ 5 = 8) or properties of operations. -

Reading Blocks.Pdf

Kindergarten Sample Literacy Block Allotted General Examples of Specific Activities Time Description • Introduce new letter/sound • Review previously learned letters/sounds Letters, Sounds, • Make/build words with sounds already learned Making/blending 30-40 • Introduce new high-frequency words words, High- minutes frequency words, • Review previously learned high-frequency words Fluency w/skills • Play word/sound wall game(s) • Use letter/sound fluency activities • Use word fluency activities • Introduce new skill 10-15 Phonological • Review previously-learned skill(s) minutes awareness • Play game with skill(s) (pocket chart games, kinesthetic movement games, etc.) • Introduce strategy to be focused on • Read a text aloud to reinforce this strategy – stop occasionally to think aloud about how you’re using strategy as you read text 20-25 • Use a graphic organizer to help students organize information/ Comprehension minutes thinking • Have students write/draw something related to their using the strategy (e.g., main idea sentence, summary, question they have, word they had difficulty understanding, mental image(s) they created as you read) • Introduce 2-4 words each day and preteach them using student- friendly definitions, examples, nonexamples, visuals, etc. Read aloud 10-15 focused on • Read text (or part of text) aloud with these words in it; stop when minutes vocabulary come to word and review word’s meaning in context • After reading, review words using graphic organizer or other activity (role playing, drawing a picture of word,