An Exploration of the Sustainable and Aesthetic Possibilities of 3D Printing Onto Textiles As an Alternative to Traditional Surf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jan's Bonus Embellishment Tips

Jan's Bonus Embellishment Tips BONUS! Add a sliver of color to your quilting! This technique is simple and effective for adding a touch of color and style to any quilt project. You'll see this technique on many of Jan's quilts. We are going to make a sample that you'll keep in your notebook for reference. Adding a sliver of color – Determine the width for the accent color. For our sample, we will make a 1/4" sliver of color between two strips of fabric. You can see this effect by examining Jan's Spiral Lone Star quilt (look at the outer diamond units nearest the binding). a – Two fabrics, joined by a single seam. b – Determine the desired width of the accent strip. Add 1/4" seam allowance. Multiply X 2 for accent strip width. c – The same two fabrics plus a contrasting accent strip, attached to the left fabric. For your samples – Cut: 1 – 2" strip of fabric, selvage to selvage. sub-cut into into two pieces. Cut : 1 – 1" x 12" strip of accent color – choose cotton or lamé fabric. Follow the steps below. Attach the samples to the pages and keep in your notebook. 1 – Two 2" strips of fabric one 1" strip of accent color (white strip in illustrations) 2 – Set the sewing machine to stitch at 1/2" by positioning a ruler beneath the presser foot. Lower the needle to touch the 1/2" 2 – Option: add blue tape to follow mark. Lower the presser foot to hold the ruler in place. -

23. Embroidery As an Embellishment in Fabric Decoration

EMBROIDERY AS AN EMBELLISHMENT IN FABRIC DECORATION By OLOWOOKERE PETER OLADIPO Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Federal College of Education, Osiele, Abeokuta. Abstract Nigeria is endowed with abundant human, natural and material resources, which could be used in different vocational practices. Practitioners have consistently practiced their art with attention to uniqueness and high quality forms, styles and content. Embroidery as a decorative process in Art has played principal roles in entrepreneurship development. Hence, this paper made a critical analysis of the forms, content and significant of embroidery in art, the thread colours, fabric motifs and pattern suitable for a successful embroidery design would also be considered. The general conclusion is that if embroidery is properly done, it would increase the embroiderers sense of creativity in our societal growth and the interested individual should be encourage to learn the craft so that the tradition will remain forever. Embroidery is an interesting stitching technique by which coloured threads, generally of silk or wool are used with a special needle to make a variety of stitches, and it is used to make an attractive design on garment, wall hanging or upholstery pieces. In Nigeria today, embroidery clothing are used far and wide and its unique feature and elegance remain the ability to trill and appeal to the people’s fervent love for it whereby the artisan considered different textile materials such as guinea brocade, damask and bringing out the significance of thread with which it is worked. Ojo (2000) defined, embroidery as an art of making pattern on textiles, leather, using threads of wool, linen, silk and needle. -

Expression2038 - 2048

expression2038 - 2048 Owner’s manual This household sewing machine is designed to comply with IEC/EN 60335-2-28 and UL1594 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using an electrical appliance, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: Read all instructions before using this household sewing machine. DANGER - To reduce the risk of electric shock: • A sewing machine should never be left unattended when plugged in. Always unplug this sewing machine from the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning. • Always unplug before relamping. Replace bulb with same type rated 5 Watt. WARNING - To reduce the risk of burns, fi re, electric shock, or injury to persons: • Do not allow to be used as a toy. Close attention is necessary when this sewing machine is used by or near children or infi rm person. • Use this sewing machine only for its intended use as described in this manual. Use only attachments recommended by the manufacturer as contained in this manual. • Never operate this sewing machine if it has a damaged cord or plug, if it is not working properly, if it has been dropped or damaged, or dropped into water. Return the sewing machine to the nearest authorised dealer or service center for examination, repair, electrical or mechanical adjustment. • Never operate the sewing machine with any air openings blocked. Keep ventilation openings of the Sewing machine and foot controller free from the accumulation of lint, dust, and loose cloth. • Keep fi ngers away from all moving parts. Special care is required around the Sewing machine needle. • Always use the proper needle plate. -

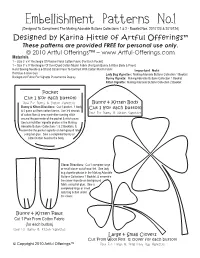

Embellishment Patterns No.1 (Designed to Compliment the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 - Booklet Nos

Embellishment Patterns No.1 (Designed To Compliment The Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 - Booklet Nos. 2010123 & 2010124) Designed by Karina Hittle of Artful Offerings™ These patterns are provided FREE for personal use only. © 2010 Artful Offerings™ ~ www.Artful-Offerings.com Materials 1 ~ Size 3” x 4” Rectangle Of Plaid or Floral Cotton Fabric {For Each Pocket} 1 ~ Size 3” x 5” Rectangles Of Over-Dyed Cotton Muslin Fabric {For Each Bunny & Kitten Body & Paws} Hand Sewing Needle & 6-Strand Cotton Floss To Contrast With Cotton Muslin Fabric Important Note Hot Glue & Glue Gun Lady Bug Vignettes: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 1 Booklet Background Fabric For Vignette Placement & Display Bunny Vignette: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 1 Booklet Kitten Vignette: Making Adorable Buttons Collection 2 Booklet Pocket Cut 1 (for each button) Used For Bunny & Kitten Vignettes Bunny & Kitten Body Bunny & Kitten Directions: Cut 1 pocket , 1 body Cut 1 (for each button) & 2 paws out from cotton fabrics. Use 3-6 strands Used For Bunny & Kitten Vignettes of cotton floss & sew a primitive running stitch around the perimeter of the pocket & stitch paws. See bunny/kitten vignette photos in the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 & 2 Booklets, & assemble the pocket vignette on background fabric using hot glue. Sew a completed bunny or kitten button head to the body. Clover Directions: Cut 1 complete large or small clover out of wool felt. See lady bug vignette photos in the Making Adorable Buttons Collections 1 Booklet, & assemble the clover vignette on background fabric using hot glue. Sew a completed large or small lady bug button under the clover. -

Bobbinwork Basics by Jill Danklefsen

SPECIAL CLASSROOM EDITION BOBBINWORK BASICS BY JILL DANKLEFSEN obbinwork is a technique that places heavy decorative 4. The type of stitch chosen as well as the type of “bobbin yarn” Bthreads on the surface of the fabric, sewn as machine-fed selected will dictate how loose the tension needs to be adjusted decorative stitches or as freemotion stitches. Typically, these on the bobbin case. threads, yarns, and cords are too large to fit through the eye of the sewing machine needle. So, in order to achieve a “stitched 5. Remember the rule of tension adjustment --“Righty, Tighty -- look”, you sew with the heavy decorative thread wound onto a Lefty, Loosey” bobbin and placed in the bobbin case of the machine. 6. Use a “construction quality” thread on the “topside” of your machine, as the needle tension will usually be increased. Think of the top thread as literally pulling the “bobbin yarn” into place to form the stitch pattern. 7. Bobbins can be wound by hand or by machine. Whenever possible, wind the bobbin using the bobbin winder mechanism on the machine. This will properly tension the “bobbin yarn” for a better stitch quality. 8. Bobbinwork can be sewn with the Feed dogs up or down. If stitching freemotion, a layer of additional stabilizer or the use of a machine embroidery hoop may be necessary. 9. Select the proper presser foot for the particular bobbinwork YARNS AND THREADS SUITABLE FOR BOBBINWORK technique being sewn. When working with the heavier “bobbin yarns”, the stitches produced will be thicker. Consider selecting • Yarns (thinner types, often a foot with a large indentation underneath it, such as Foot used for knitting machines) #20/#20C.This foot will ride over the stitching much better. -

MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES 7640 INTRODUCTION Welcome

INSTRUCTION MANUAL MANUEL D’INSTRUCTION MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES 7640 INTRODUCTION Welcome Welcome to the SINGER® family and CONGRATULATIONS on purchasing a brand new SINGER® sewing machine! The SINGER® brand has stood for quality in sewing for over 160 years. We design our machines for sewists of all skill levels so that the joy of sewing, creating, do-it-yourself, crafting and more can be enjoyed by all. It is important to us that you have the easiest and most successful sewing experience. We have provided an instruction manual with easy-to-understand graphics and step-by-step instructions. Additional assistance, by region, may be found on the web at www.singer.com. We’re ready to help and hope that you enjoy your SINGER® sewing machine. Happy Sewing! 2 INTRODUCTION Important Safety Instructions This household sewing machine is designed to comply with IEC/EN 60335-2-28 and UL1594. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using an electrical appliance, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: Read all instructions before using this household sewing machine. Keep the instructions in a suitable place close to the machine. Make sure to hand them over if the machine is given to a third party. DANGER - To reduce the risk of electric shock : - A sewing machine should never be left unattended when plugged in. Always unplug this sewing machine from the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning, removing covers, lubricating or when making any other user servicing adjustments mentioned in the instruction manual. WARNING - To reduce the risk of burns, fire, electric shock, or injury to person : - Do not allow to be used as a toy. -

Design Iterations Through Fusion of Additive and Subtractive Design

DESIGN ITERATIONS THROUGH FUSION OF ADDITIVE AND SUBTRACTIVE DESIGN A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Gordon Stumpo May 2016 i Thesis written by Gordon Stumpo B.A., Washington State University, 2014 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Vince Quevedo, Thesis Supervisor Brian Peters, Committee Member Margarita Benitez, Committee Member Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………………………….……….…….….vi LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………………...……….………..xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………………………………...………..………..xii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………..………….13 Concept……………………………………………………………………………………...................................13 Design Framework…………………………………………………………………………………………..…13 Surface and Structure Frameworks…………………………………………………………….….……14 Additive Design…………………………………………………………………………………………..…..….18 Subtractive Design……………………………………………………….……………………………....….…18 Tension…………….……………………………………………………………………………….…………..…..18 Price Point…………….…………………………….………………………………………………………...…..19 Personal Skills & Background…………….……………………………………………………….…..…..19 Problem Statement & -

CLEANING and RESTORING BUTTONS by Lisa Schulz Button Images

CLEANING AND RESTORING BUTTONS by Lisa Schulz Button Images www.buttonimages.com Before cleaning your buttons you will need to know what materials the buttons are made of and have a knowledge of their construction and makeup, because the various materials are treated differently. Many of the following cleaning techniques have been suggested by other collectors. They have not all been tested by this writer. There are several things that this writer has used very successfully, and would recommend keeping in your cleaning supply kit. They are: • Polishing Cloth (see my catalog or web site for ordering Polishing Cloths.) With use the cloth will get black, but it still continue to clean your buttons. I keep one for metal buttons and another (cleaner one) for other materials. Do not wash the Polishing Cloth. • Brass Brush (see my catalog or web site for ordering Brass Cleaning Brushes.) Can be used on brass buttons without scratching. Can be used on other types of metal with a little more caution (brush gently). Use caution on fine silver and pewter. • Gray ink eraser (found with school supplies or an office supply store.) • Lead Pencil. • Baby oil, mineral oil or gentle furniture polish used with a sort cloth. • Clean dry tooth brush. Most buttons can be brushed with a tooth brush to remove dirt or dust that is on the surface or in cracks. • Dremel with eraser wheels and brass brushes. (Can be purchased at some WalMart stores, some hobby stores or hardware stores) – The eraser wheels come in black, blue, and pink, with black being the harshest and the pink being the most gentle. -

Modern Architecture and Luxury: Aesthetics and the Evolution of the Modern Subject

arts Book Review Modern Architecture and Luxury: Aesthetics and the Evolution of the Modern Subject Joanna Merwood-Salisbury School of Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] Received: 30 July 2019; Accepted: 31 July 2019; Published: 6 August 2019 Abstract: A book review of Robin Schuldenfrei, Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900–1933 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). This book challenges the canonical interpretation of two of the most revered institutions in the history of modern architecture—the Werkbund and the Bauhaus—and presents a critical interpretation of the relationship between modern architecture and luxury, which first appeared a generation ago. Keywords: architecture; design; luxury; AEG; Werkbund; Bauhaus; Germany; modernism Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900–1933 challenges the canonical interpretation of two of the most revered institutions in the history of modern architecture—the Werkbund and the Bauhaus—and presents a critical interpretation of the relationship between modern architecture and luxury, which first appeared a generation ago. In the founding documents of the modern movement, architecture and luxury were framed as irreconcilable opposites. To be modern was to reject ornament—the traditional aesthetic signifier of social status (Veblen [1899] 1994; Sombart [1913] 1967; Massey 2004). Cheapened by thoughtless application, ornament was seen as wasteful and excessive—a superfluous excrescence to be sloughed off through purifying processes of subtraction and elimination. Framed in terms of social evolution, to take pleasure in ornament was evidence of a primitive or retarded stage of racial development (Loos [1908] 1970; Muthesius [1903] 1994). -

EMBELLISHMENT Author.Name Copy.Number Copy.Shelfmark Copy.Site Isbn Title

EMBELLISHMENT author.name copy.number copy.shelfmark copy.site isbn title EDDY ELLEN ANNE 1175 EM/EDD York 156477189X THREAD MAGIC: the enchanted world of Ellen Anne Eddy HUBBARD LIZ 1464 EM/HUB Bolton 07153 90007 THREAD PAINTING SIMMONS JUDY 1154 EM/SIM Bolton 1564771628 MACHINE NEEDLELACE & OTHER EMBELLISHMENT TECHNIQUES HUBBARD LIZ 285 EM/HUB York 715390007 THREAD PAINTING ECKLEY GINNY 1038 EM/ECK Bolton 1564770834 QUILTED SEA TAPESTRIES: TECHNIQUES FOR MACHINE-EMBROIDERED DESIGN BOND DOROTHY 31 EM/BON York 0-960686-0-5 CRAZY QUILT STITCHES LEHMAN LIBBY 1196 EM/LEH York 1564772020 THREADPLAY : MASTERING MACHINE EMBROIDERY TECHNIQUES NILSSON SHIRLEY 505 EM/NIL Bolton STITCHING FREE. EASY MACHINE PICTURES COLEMAN ANNE 134 EM/COL Bolton 713433108 THE CREATIVE SEWING MACHINE CAMPBELL-HARDING, VALERIE & WATTS, PAMELA 1463 EM/CAM Bolton 071345797X MACHINE EMBROIDERY: STITCH TECHNIQUES FILSON YOLANDE & PRZYBYLSKI ROBERTA 181 EM/FIL Bolton 1564770729 THE HEIRLOOM QUILT HOLT ALISON 1434 EM/HOL Bolton 713465271 MACHINE EMBROIDERED LANDSCAPES THOMPSON ANGELA 1570 EM/THO York 600305031 THE COMPLETE BOOK OF THE SEWING MACHINE CAMPBELL-HARDING VALERIE 1583 EM/CAM Bolton 713481595 MACHINE EMBROIDERY :STITCHED PATTERNS STANGNESS LORRAINE 1697 EM/STA Bolton MAGICAL MACHINE QUILTING & EMBELLISHMENT DREXLER FRED & JOYCE 1792 EM/DRE Bolton PATCHWORK CONCEPTS IN SULKY: RAYON & DECORATIVE METALLIC THREADS MUNNI SRIVASTAVA 000N9 EM/SRI Bolton 0-7134-8709-7 EMBROIDERY TECHNIQUES FROM EAST AND WEST CAMPBELL-HARDING & GREY 112 EM/CAM Bolton 0-7134-8653-8 LAYERS -

The Decorative in Twentieth Century Art: a Story of Decline and Resurgence

THE DECORATIVE IN TWENTIETH CENTURY ART: A STORY OF DECLINE AND RESURGENCE PAMELA GAUNT A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Art Theory Postgraduate Board, University of New South Wales August 2005 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: GAUNT First name: Pamela Other name/s: Mary Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MA (Art Theory) School: School of Art History/Theory Faculty: COFA Title: The Decorative in Twentieth Century Art: A Story of Decline and Resurgence. Abstract: This thesis tracks the complex relationship between visual art and the decorative in the Twentieth Century. In doing so, it makes a claim for the ongoing interest and viability of decorative practices within visual art, in the wake of their marginalisation within Modernist art and theory. The study is divided into three main sections. First, it demonstrates and questions the exclusion of the decorative within the central currents of modernism. Second, it examines the resurgence of the decorative in postmodern art and theory. This section is based on case studies of a number of postmodern artists whose work gained notice in the 1980s, and which evidences a sustained engagement with a decorative or ornamental aesthetic. The artists include Rosemarie Trockel, Lucas Samaras, Philip Taaffe, and several artists from the Pattern and Decoration Painting Movement of the 1970s. The final component of the study investigates the function and significance of the decorative in the work of a selection of Australian and international contemporary artists. The art of Louise Paramor, Simon Periton and Do-Ho Suh is examined in detail. -

Decorative Pintuck Foot #46C Is Designed to Add a 2-Step Embellishment to Fabric

Decorative Pintuck Created by Susan Beck Foot #46C Decorative Pintuck Foot #46C is designed to add a 2-step embellishment to fabric. First, widely spaced double needle pintucks and second, decorative stitches fill the spaces between the pintucks. The acrylic sole of the presser foot offers a clear view of the stitching area. Decorative Pintuck Foot #46C works on all current BERNINA models, those with 9mm and those with 5.5mm stitch width. Insert a 3.0mm double needle into the machine and thread with two spools of thread (see right). Corded Pintucks Mark a line on the fabric for the first pintuck. Following the line, stitch the Add body and dimension to pintucks by stitching first pintuck. over cord. Use a narrow cord such as gimp cord, perle cotton, topstitching thread, crochet cotton, Position the pintuck in one of the grooves to get the or embroidery floss. Position the cord for stitching desired spacing. Stitch a second pintuck. using one of the methods below. Continue repositioning foot and aligning the pintucks in Thread narrow cord the groove until the desired number of pintucks are sewn. through bobbin area and up through hole in Place 1-2 layers of stabilizer behind the fabric. Align the front of needle opening foot over the pintucks and select a decorative stitch; sew (works with models that the stitch between the pintucks. have the type of stitch plate shown) Double Needle Threading Place one spool on the vertical pin and one on the Another option is the horizontal spool pin, threading them together ex- Pintuck Attachment cept in the following two areas: that holds the cord in Place one thread on each side of tension disc front of the needle Bypass the last guide with one of the threads (works with all models) Note: 8 Series models must be threaded manually Visit bernina.com: Projects ● Webinars ● Promotions ©2014 BERNINA of America Page 1 of 1 .