Immigration Unilateralism and American Ethnonationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Conservative Grassroots Coalition Letter

November 18, 2020 Dear Texas House Republicans, Once again Democrat efforts to turn Texas blue were soundly rejected by voters across the Lone Star State. While we continue to wait for election results to settle here in Texas and across the nation, it is obvious that Texas voters have delivered a mandate for conservative reform to their elected officials. While our control over national affairs is limited, Republican control of Texas is absolute. The GOP holds majorities in both chambers of the Texas Legislature. It also holds the governor’s office, the lieutenant governor’s office, and every other statewide office. Indeed, Republicans have majorities sufficient to enact any reform they wish – apart from state constitutional amendments – without securing a single Democrat vote. Texans voted for that result and Texans expect that from their elected officials. To be clear, Texas voters did not vote for bipartisan capitulation or compromise with Democrats, they voted for conservative Republican policies to be enacted. Texas has not elected a Democrat statewide since 1994. Texas voters’ decision to again shut Democrats out of statewide office and return Republican majorities to our Legislative and Congressional Delegations signals voters want the Republican Party of Texas Platform rigorously pursued and they expect results – not excuses. In order to advance the Republican Party of Texas Platform and its 87th Session Legislative Priorities, any Republican campaigning for Speaker of the Texas House should and must commit the following to Republican voters: ● Each Republican Party of Texas legislative priority will receive a vote on the floor of the Texas House. ● All House committees shall be chaired by Republicans and shall be composed of a majority of Republicans. -

EXECUTIVE INSIGHT BRIEF - March 3, 2017 Date: Monday, March 06, 2017 9:20:37 AM

From: Craig Quigley To: Craig Quigley Subject: EXECUTIVE INSIGHT BRIEF - March 3, 2017 Date: Monday, March 06, 2017 9:20:37 AM Ladies & Gentlemen, below please find this week’s edition of Executive Insight Brief from The Roosevelt Group. Craig R. Quigley Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy (Ret.) Executive Director Hampton Roads Military and Federal Facilities Alliance 757-644-6324 (Office) 757-419-1164 (Cell) EXECUTIVE INSIGHT BRIEF | March 3, 2017 TOP STORIES JEFF SESSIONS RECUSES HIMSELF FROM RUSSIA INQUIRY. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, facing a storm of criticism over newly disclosed contacts with the Russian ambassador to the United States, recused himself on Thursday from any investigation into charges that Russia meddled in the 2016 presidential election. Read more ISIS DUMPED BODIES IN A DESERT SINKHOLE. IT MAY BE YEARS BEFORE WE KNOW THE FULL SCALE OF THE KILLINGS. The horror stories about the Islamic State’s mass killings at a cavernous hole in the desert near Mosul became legendary over the years. Soon after the group took control of the Iraqi city more than 2½ years ago, the 100-foot-wide sinkhole five miles southwest of the airport became a site for summary executions. Read more TRUMP’S DEFENSE SPENDING INCREASE ISN’T EXTRAORDINARY, BUT ITS IMPACT COULD BE. On Monday, the White House announced the first few details of President Trump’s budget proposal, expected to be released within the next month. He plans to increase defense spending by $54 billion — about 10 percent of its 2017 budget. In his joint address to Congress Tuesday night, he falsely called it “one of the largest increases in national defense spending in American history.” Read more KIM JONG-NAM KILLING: N KOREAN SUSPECT TO BE DEPORTED. -

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

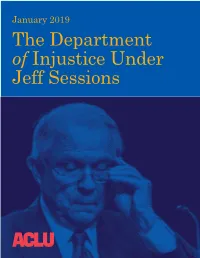

The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions the Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions January 2019

January 2019 The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions January 2019 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 VOTING RIGHTS 2 IMMIGRANTS' RIGHTS 3 CRIMINAL JUSTICE 6 DISABILITIES 9 HEALTH CARE 10 RELIGIOUS LIBERTY 10 LGBT RIGHTS 10 CRIMINALIZATION OF POVERTY 11 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 12 WORKERS' RIGHTS 12 FREE PRESS AND PROTEST RIGHTS 12 PRIVACY RIGHTS 13 SEPARATION OF POWERS 15 POLITICIZED ANALYSIS AND PERSONNEL 15 INTRODUCTION Jeff Sessions' tenure at the Department of Justice was a national disgrace. As attorney general, he was entrusted to enforce federal laws — including civil rights laws — and secure equal justice for all. Instead, Sessions systematically undermined our civil rights and liberties, dismantled legal protections for the vulnerable and persecuted, and politicized the Justice Department's powers in ways that threaten American democracy. When President Donald Trump and his political appointees elsewhere in his administration tried to do the same, often in violation of the Constitution, Sessions' Justice Department went into overdrive manufacturing legal and factual justifications on their behalf and defending the unjust actions in court. Sessions was aided by Trump-approved appointees who often overruled career attorneys and staffers committed to a high level of neutral professionalism. Under Sessions' political leadership, these Trump appointees have inflicted significant damage in the past two years. Together they have threatened the First Amendment rights of the press and protesters, targeted the communities Trump disfavors through discriminatory policies and tactics, attacked the ability of ordinary citizens to vote and change their elected government, vindictively retaliated against perceived political opponents, and thwarted congressional oversight of the Justice Department's activities. -

The Impact of the New Right on the Reagan Administration

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THE IMPACT OF THE NEW RIGHT ON THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION: KIRKPATRICK & UNESCO AS. A TEST CASE BY Isaac Izy Kfir LONDON 1998 UMI Number: U148638 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U148638 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this research is to investigate whether the Reagan administration was influenced by ‘New Right’ ideas. Foreign policy issues were chosen as test cases because the presidency has more power in this area which is why it could promote an aggressive stance toward the United Nations and encourage withdrawal from UNESCO with little impunity. Chapter 1 deals with American society after 1945. It shows how the ground was set for the rise of Reagan and the New Right as America moved from a strong affinity with New Deal liberalism to a new form of conservatism, which the New Right and Reagan epitomised. Chapter 2 analyses the New Right as a coalition of three distinctive groups: anti-liberals, New Christian Right, and neoconservatives. -

On Nixon, 25 on Kissinger, and More Than 600 on Mao

Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Powers Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World Roundtable Review Reviewed Works: Robert Dallek. Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power. New York: Harper Collins, 2007. 740 pp. $32.50. ISBN-13: 978-0060722302 (hardcover). Margaret MacMillan. Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World. New York: Random House, 2007. 404 pp. $27.95. ISBN-13: 978-1-4000- 6127-3 (hardcover). [Previously published in Canada as Nixon in China: The Week that Changed the World and in the UK as Seize the Hour: When Nixon Met Mao.]. Roundtable Editor: David A. Welch Reviewers: Jussi M. Hanhimäki, Jeffrey Kimball, Lorenz Lüthi, Yafeng Xia Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/NixonKissingerMao-Roundtable.pdf Your use of this H-Diplo roundtable review indicates your acceptance of the H-Net copyright policies, and terms of condition and use. The following is a plain language summary of these policies: You may redistribute and reprint this work under the following conditions: Attribution: You must include full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. Nonprofit and education purposes only. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Enquiries about any other uses of this material should be directed tothe H-Diplo editorial staff at h- [email protected]. H-Net’s copyright policy is available at http://www.h-net.org/about/intellectualproperty.php . -

Using Activists' Pairwise Comparisons to Measure Ideology

Is John McCain more conservative than Rand Paul? Using activists' pairwise comparisons to measure ideology ∗ Daniel J. Hopkins Associate Professor University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Hans Noely Associate Professor Georgetown University [email protected] April 3, 2017 Abstract Political scientists use sophisticated measures to extract the ideology of members of Congress, notably the widely used nominate scores. These measures have known limitations, including possibly obscuring ideological positions that are not captured by roll call votes on the limited agenda presented to legislators. Meanwhile scholars often treat the ideology that is measured by these scores as known or at least knowable by voters and other political actors. It is possible that (a) nominate fails to capture something important in ideological variation or (b) that even if it does measure ideology, sophisticated voters only observe something else. We bring an alternative source of data to this subject, asking samples of highly involved activists to compare pairs of senators to one another or to compare a senator to themselves. From these pairwise comparisons, we can aggregate to a measure of ideology that is comparable to nominate. We can also evaluate the apparent ideological knowledge of our respondents. We find significant differences between nominate scores and the perceived ideology of politically sophisticated activists. ∗DRAFT: PLEASE CONSULT THE AUTHORS BEFORE CITING. Prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association in Chicago, April 6-9, 2017. We would like to thank Michele Swers, Jonathan Ladd, and seminar participants at Texas A&M University and Georgetown University for useful comments on earlier versions of this project. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28, 2017 Thank you, Chris, for that kind introduction and for your tremendous work on behalf of our Second Amendment. Thank you very much. I want to also thank Wayne LaPierre for his unflinching leadership in the fight for freedom. Wayne, thank you very much. Great. I'd also like to congratulate Karen Handel on her incredible fight in Georgia Six. The election takes place on June 20. And by the way, on primaries, let's not have 11 Republicans running for the same position, okay? [Laughter] It's too nerve-shattering. She's totally for the NRA, and she's totally for the Second Amendment. So get out and vote. She's running against someone who's going to raise your taxes to the sky, destroy your health care, and he's for open borders—lots of crime—and he's not even able to vote in the district that he's running in. Other than that, I think he's doing a fantastic job, right? [Laughter] So get out and vote for Karen. Also, my friend—he's become a friend—because there's nobody that does it like Lee Greenwood. Wow. [Laughter] Lee's anthem is the perfect description of the renewed spirit sweeping across our country. And it really is, indeed, sweeping across our country. So, Lee, I know I speak for everyone in this arena when I say, we are all very proud indeed to be an American. -

Conservatism from Taft to Trump Syllabus

Dr. Brian Rosenwald Office: Fels 31 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: History 204-302: Conservatism From Taft to Trump The early 1950s may have been the nadir for modern American conservatism. Conservative hero Robert Taft had lost the Republican nomination for President to a more moderate candidate for the third time, many in the Republican Party had moved to accept some of the most popular New Deal programs, and a moderate, internationalist consensus had taken hold in the country. Yet, from these ashes, conservatism rose to become a potent political force in the United States over the last half century. This seminar explores the contours of that rise, beginning with infrastructure laid and coalitions forged in the 1950s. We will see how conservatives built upon this infrastructure to overcome Barry Goldwater’s crushing 1964 defeat to elect one of their own, Ronald Reagan, president in 1980. Reagan’s presidency transformed the public philosophy and helped shape subsequent American political development. Our study of conservatism will also include the struggles that conservatives confronted in trying to enact their ideas into public policy, and the repercussions of those struggles. We will explore conservatism’s triumphs and failures politically, as well as the cultural changes that have helped, hindered, and shaped its rise. In many ways, this class is a study in the transformation of American politics and in American culture over the last sixty-five years. Its focus is on the hows and the whys of the rise of conservatism from the low point of the early 50s to the rise of the Tea Party and Trumpism in the 2000s and 2010s. -

Sen. Jeff Sessions's Record on Criminal Justice

Analysis: Sen. Jeff Sessions’s Record on Criminal Justice By Ames C. Grawert This analysis provides a brief summary of Sen. Jeff Sessions’s past statements, votes, and practices relating to criminal justice. Specifically, this analysis finds that: • Sen. Sessions opposes efforts to reduce unnecessarily long federal prison sentences for nonviolent crimes, despite a consensus for reform even within his own party. In 2016, he personally blocked the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, a bipartisan effort spearheaded by Sens. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), Mike Lee (R-Utah), and John Cornyn (R- Texas), and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), and supported by law enforcement leadership. As Attorney General, Sen. Sessions could stall current congressional efforts to pass this legislation to recalibrate federal sentencing laws. • Drug convictions made up 40 percent of Sen. Sessions’s convictions when he served as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama — double the rate of other Alabama federal prosecutors. Today, state and federal law enforcement officers have begun to focus resources on violent crime, and away from archaic drug war policies. But Sen. Sessions continues to oppose any attempts to legalize marijuana and any reduction in drug sentences. As Attorney General, Sen. Sessions could direct federal prosecutors to pursue the harshest penalties possible for even low-level drug offenses, a step backward from Republican- supported efforts to modernize criminal justice policy. • Unlike many Republican legislators, Sen. Sessions supports the use of “civil asset forfeiture,” which allows police to confiscate property from people who may not even be accused of a crime. -

CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: the GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Sc

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Science, University of Pittsburgh, 2001 M. A. in Communication, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eric Edward English It was defended on November 13, 2013 and approved by Don Bialostosky, PhD, Professor, English Gordon Mitchell, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication John Poulakos, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication Dissertation Director: John Lyne, PhD, Professor, Communication ii Copyright © by Eric Edward English 2013 iii CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG Eric Edward English, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Barry Goldwater’s 1960 campaign text The Conscience of a Conservative delivered a message of individual freedom and strictly limited government power in order to unite the fractured American conservative movement around a set of core principles. The coalition Goldwater helped constitute among libertarians, traditionalists, and anticommunists would dominate American politics for several decades. By 2008, however, the cracks in this edifice had become apparent, and the future of the movement was in clear jeopardy. That year, Ron Paul’s campaign text The Revolution: A Manifesto appeared, offering a broad vision of “freedom” strikingly similar to that of Goldwater, but differing in certain key ways. This book was an effort to reconstitute the conservative movement by expelling the hawkish descendants of the anticommunists and depicting the noninterventionist views of pre-Cold War conservatives like Robert Taft as the “true” conservative position. -

John F. Kennedy We Are All Mortal EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

John F. Kennedy We are all mortal EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: America. 1963. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR CLIP: I'm happy to talk with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. JOHN F. KENNEDY CLIP: I realize the pursuit of peace is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war. And frequently, the words of the pursuers fall on deaf ears. But we have no more urgent task. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR CLIP: Five score years ago, a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation. JOHN F. KENNEDY CLIP: It ought to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color. In short, every American ought to have the right to be treated as he would wish to be treated -- as one would wish his children to be treated. But this is not the case. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR CLIP: This momentous decree came as a grand beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.