A Conversation with Laurie Carlos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bam 2016 Annual Report

BAM 2016 2 1ANNUAL REPORT 0 6 BAM’s mission is to be the home for adventurous artists, audiences, and ideas. 3—6 Community, 31–33 GREETINGS DanceMotion USASM, 34–35 Chair Letter, 4 Visual Art, 36–37 President & Executive Producer’s Letter, 5 Membership, 38 BAM Campus, 6 Membership, 37—39 7—35 40—47 WHAT WE DO WHO WE ARE 2015 Next Wave Festival, 8–10 BAM Board, 41 2016 Winter/Spring Season, 11–13 BAM Supporters, 42–45 Also On Stage, 14 BAM Staff, 46–47 BAM Rose Cinemas, 15–20 48—50 First-run Films, 16 NUMBERS BAMcinématek, 17–18 BAM Financial Statements, 49–50 BAMcinemaFest, 19 HD Screenings, 20 51—55 BAMcafé Live, 21–22 THE TRUST BAM Hamm Archives, 23 BET Chair Letter, 52 Digital Media, 24 BET Donors, 53 Education & Humanities, 25–30 BET Financial Statements, 54–55 2 TKTKTKTK Cover: Urban Bush Women in Walking with ‘Trane| Photo: Julieta Cervantes Greetings GREETINGS 3 TKTKTKTK 2016 Winter/Spring | Royal Shakespeare Company in Henry IV Part I | Photo: Richard Termine Change is anticipated, expected, welcomed. — Alan H. Fishman Dear Friends, As you all know, and perhaps celebrated (!), Anne Bogart, Ivo van Hove, Long time trustee Beth Rudin Dewoody As I end my leadership role, I want to I stepped down as chairman of this William Kentridge, and many others. became an honorary trustee. Mark Jackson express my thanks to all I have met and miraculous institution effective December and Danny Simmons, both great trustees, worked with along the way. Together we have 31, 2016. -

The Civilians"

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2012 A Versatile Group of Investigative Theater Practitioners: An Examination and Analysis of "The Civilians" Kimberly Suzanne Peterson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Peterson, Kimberly Suzanne, "A Versatile Group of Investigative Theater Practitioners: An Examination and Analysis of "The Civilians"" (2012). Master's Theses. 4158. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.n3bg-cmnv https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A VERSATILE GROUP OF INVESTIGATIVE THEATER PRACTITIONERS: AN EXAMINATION AND ANALYSIS OF “THE CIVILIANS” A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Theater Arts San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Kimberly Peterson May 2012 © 2012 Kimberly Peterson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled A VERSATILE GROUP OF INVESTIGATIVE THEATER PRACTITIONERS: AN EXAMINATION AND ANALYSIS OF “THE CIVILIANS” by Kimberly Peterson APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE, RADIO-TELEVISION-FILM, ANIMATION & ILLUSTRATION SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May -

Nawang Khechog the Great Arya Tara Tibetan Meditation Music 5:11

Playlists by David Ruekberg Dance to Awaken the Heart, Rochester, NY #27: January 28, 2017 Artist Song Title Album Length Nawang Khechog The Great Arya Tara Tibetan Meditation Music 5:11 Maneesh de Moor Morning Praise Om Deeksha 8:54 Ernst Reijseger Homo Spiritualis Cave Of Forgotten Dreams (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) 2:21 Hukwe Zawose Nhongolo The Essential Guide To Africa 8:54 Dead Can Dance Nierika Memento 5:46 Deva Premal Guru Rinpoche Mantra Deva Lounge 7:23 Balligomingo Purify Absolute More Relaxed [Disc 2] 4:13 Manu Dibango Bessoka (Version Courte) The Essential Guide To Africa 3:28 Miriam Makeba Pata Pata 2000 Homeland 3:49 Thievery Corporation The Lagos Communique African Groove 3:55 Christina Aguilera featuring Steve Winwood Makes Me Wanna Pray Back To Basics 4:11 The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows (Remastered) Revolver (Remastered) 2:59 Brian Eno & Rick Holland Glitch Drums Between The Bells 2:58 Sean Dinsmore Mangalam (Chillums at Dawn Remix) Dakini Lounge: Prem Joshua Remixed 6:00 India.Arie Slow Down Voyage To India 3:53 Jai Uttal Guru Bramha Shiva Station (Bonus Edition) 4:24 Bon Iver Lisbon, OH Bon Iver 1:34 Ulrich Schnauss Amaris Passage 5:20 David Ruekberg Silence_5s.mp3 Silence 0:05 Itzhak Perlman Bach: Violin Partita #2 In D Minor, BWV 1004 - 3. Sarabanda Bach: Sonatas & Partitas For Solo Violin [Disc 2] 3:52 Anoushka Shankar Ancient Love Rise 11:08 Ray Lynch Her Knees Deep In Your Mind Conversations With God 6:19 Soloists of the Ensemble Nipponia [Shakuhachi, Shamisen, Biwa, EsashiKoto] Oiwake ("Esashi Pack-horseman's -

Participant Biographies

Participant Biographies ADETOLA ABIADE the recently completed Denver International Airport and Traces of the Trade the Central American Resource and Education Center. [email protected] Farhad also works closely with Baca’s UCLA class Adetola Abiade is a native of Providence, RI. Adetola has entitled “Beyond the Mexican Mural.” recently been named dialogue coordinator for the film initiative titled Trace of the Trade. Adetola has over 8 MICHIKO AKIBA years of professional experience including 1 0f 13 Managing Director, Hoshinofurusato Foundation selected from 2000 into the highly competitive [email protected] Management. program for Chase Manhattan Bank NY. Since November 2002, Michiko Akiba has been the Adetola also worked as a project manager deveolping managing director of Hoshinofurusato Foundation, an high level trading systems and managed change organization which manages several cultural and management initiatives at State Street Bank Boston. The recreational facilities in Hoshino Village, Fukuoka last three years were spent empowering women to prefecture, in Japan. Ms. Akiba graduated from become economically self-suffivient and prosperous Hitotsubashi University with a degree in economics and through entrepreneurship in RI and MA serving over has held positions in fields including sales promotion, 1000 small businesses. Adetola graduated with a B.S. in music, cultural journalism, and magazine marketing. She is Marketing/Sociology/English from Providence College in a graduate student of Kinki University and has studied 1995. Adetola is also certfied in Organizational Behavior public art and community arts in the United States. PARTICIPANTS Training from Brown University, Mediation, and serves as Rhode Island Small Business Development Ctr. KAREN ALDRIDGE-EASON Consultant. -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release New York Live Arts Announces Program Details and Schedule for 2014 Live Ideas Festival James Baldwin, This Time! April 23 – 27, 2014 James Baldwin, writer, January 9, 1963. Photograph by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation Highlights include a Keynote Conversation with Bill T. Jones, Carrie Mae Weems and Jamaica Kincaid, the world premiere of Nothing Personal, starring Colman Domingo, a preview of Carl Hancock Rux’s newest work Stranger On Earth and a special evening with Stew exploring his new ‘Notes of a Native Song’ Also included are the New York premiere of Charles O. Anderson’s Restless Natives, the world premiere of Dianne McIntyre’s Time is Time, an original video installation by Hank Willis Thomas, and a concluding conversation with Fran Lebowitz and Colm Tóibín New York, NY, January 15, 2014 (updated March 27, 2014) – New York Live Arts today announced the schedule of its second annual Live Ideas festival, James Baldwin, This Time! taking place April 23 – 27, 2014. Inaugurating “The Year of James Baldwin,” a city-wide celebration in 2014 - 15 of the continuing artistic, intellectual and moral presence of James Baldwin, on the occasion of what would have been his 90th year, James Baldwin, This Time! will present no fewer than 18 events in an array of theater, visual art, dance, video and literature featuring such artists as Carrie Mae Weems, Jamaica Kincaid, Suzan-Lori Parks, Stew, Carl Hancock Rux, Colman Domingo, Fran Lebowitz, Colm Tóibín, Charles O. Anderson, and Patricia McGregor. “New York Live Arts is proud to launch the monumental city-wide multidisciplinary festival The Year of James Baldwin with James Baldwin, This Time! and collaborate with such illustrious partners as Harlem Stage and the Columbia University School of the Arts,” stated Jean Davidson, Executive Director and CEO of New York Live Arts. -

Time and Again

1/30/2016 Claudia La Rocco previews the fall 2014 dance and performance calendars - artforum.com / slant login register ADVERTISE BACK ISSUES CONTACT US SUBSCRIBE search ARTGUIDE IN PRINT 500 WORDS PREVIEWS BOOKFORUM A & E 中文版 DIARY PICKS NEWS VIDEO FILM PASSAGES SLANT PERFORMANCE Time and Again links RECENT ARCHIVE 08.27.14 Jennifer Krasinski on Erin Markey, Kaneza Schaal, and Jonathan Capdevielle Claudia La Rocco on David Neumann’s I Understand Everything Better Jennifer Krasinski on Edgar Arceneaux, Wunderbaum, Walid Raad… Claudia La Rocco on ballet in and around Performa 15 Jennifer Krasinski on Basil Twist and Jack Ferver and Marc Swanson Kate Sutton on Ieva Misevičiūtė’s Lord of Beef Christopher Wheeldon, After the Rain, 2005. Performance view, June 10, 2010. Wendy Whelan and Craig Hall. Photo: Paul Kolnik. YOU ALL KNOW THE DRILL: It’s fall. There are things happening. Here are just a few of them, as filtered through a sensibility that may in no way be compatible with your own: 1. The inimitable ballerina Wendy Whelan is giving her farewell New York City Ballet performance on October 18, ending an astonishingly fertile thirtyyear run that has included collaborations with just about every ballet choreographer of note, and performances of breathtaking command and finesse. Say you were inclined to commit some sort of semiserious crime to get a ticket to a show this fall—this is the one. Otherwise, good ARCHITECTURE luck. RECENT ARCHIVE 1a. Once you fail to gain entry to Whelan, you can console your missing an electrifying moment in history by turning to a ballet star who’s just about as far away from Whelan as possible: Natalia Osipova. -

EPK 8.23.12 Updated

FESTIVAL SCREENINGS The 2011 Sundance Film Festival, Park City, Utah *WORLD PREMIERE* Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City *GOTHAM AWARD NOMINEE! Best Movie Not Playing At A Theater Near You* International Women’s Film Festival in Seoul (IWFFIS) Korea The Sarasota Film Festival, Florida The Nashville International Film Festival, Tennessee The Atlanta Film Festival, Georgia The Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival, Hawaii *WINNER! Best Feature Film Award* The Toronto Inside Out Film Festival, Canada *WOMEN’S SPOTLIGHT FEATURE* Bent Lens Cinema, Boulder, Colorado The Provincetown Film Festival, Massachusetts Rooftop Films 2011 Summer Series, New York City Frameline International LGBT Film Festival, San Francisco *WINNER! Honorable Mention: Best First Feature* The Kansas City Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Galway Film Fleadh, Ireland The Philadelphia Q Fest *Opening Night Film!* Outfest: The Los Angeles LGBT Film Festival *WINNER! Special Programming Award* Newfest: The New York Gay and Lesbian Film Festival The Vancouver Queer Film Festival Oslo Gay and Lesbian Film Festival 17th Athens International Film Festival, Greece Colorado Springs Pikes Peak Lavender Film Festival *CLOSING NIGHT FILM* Citizen Jane Film Festival, Missouri Norrköping Flimmer Film Festival, Sweden Portland Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, Oregon Tampa International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Florida *WOMEN’S GALA FILM* eQuality Film Festival 2011, Albany, NY Southwest Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, Albuquerque, New Mexico Reel Affirmations Film Festival, Washington, -

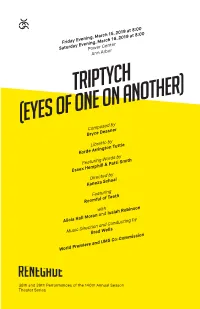

TRIPTYCH ) (EYES of ONE on ANOTHER Composed by Bryce Dessner

Friday Evening, March 15, 2019 at 8:00 Saturday Evening, March 16, 2019 at 8:00 Power Center Ann Arbor TRIPTYCH (EYES OF ONE ON ANOTHER) Composed by Bryce Dessner Libretto by Korde Arrington Tuttle Featuring Words by Essex Hemphill & Patti Smith Directed by Kaneza Schaal Featuring Roomful of Teeth with Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson Music Direction and Conducting by Brad Wells World Premiere and UMS Co-Commission 38th and 39th Performances of the 140th Annual Season Theater Series This weekend’s performances are supported by Level X Talent. This weekend’s performances are funded in part by The Wallace Foundation. Produced in residency with and commissioned by University Musical Society, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Co-produced by Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, music and artistic director. Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) was co-commissioned by BAM; Luminato Festival, Toronto, Canada; Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Athens, Greece; Cincinnati Opera, Cincinnati, OH; Cal Performances, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA; Stanford Live, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Adelaide Festival, Australia; John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts for performance as part of DirectCurrent 2019; ArtsEmerson: World on Stage, Emerson College, Boston, MA; Texas Performing Arts, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX; Holland Festival, Amsterdam; Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; the Momentary, Bentonville, AR; Celebrity Series, Boston, MA; and developed in residency with MassMOCA, North Adams, MA. Media partnership provided by WEMU 89.1 FM, Between the Lines, and Metro Times. Special thanks to Chrisstina Hamilton and the Penny Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series, Joel Howell, Amanda Krugliak and the LSA Institute for the Humanities, and Richard Meyer for their participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater's 18-City United

ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER’S 18-CITY UNITED STATES TOUR TRAVELS FROM COAST-TO-COAST FEBRUARY 3 – MAY 10 Presidential Medal of Freedom Acknowledges Powerful Legacy of Alvin Ailey that Continues to Thrive Under Leadership of Artistic Director Robert Battle Inspiring Performances by Ailey’s Extraordinary Dancers Include Alvin Ailey’s American Masterpiece Revelations and a Wide Variety of Premieres Highlighted by a Timely Tribute to a Civil Rights Icon - ODETTA Company Premieres of After the Rain Pas de Deux by Christopher Wheeldon, Uprising by Hofesh Shechter, and Suspended Women by Jacqulyn Buglisi Announcement of 2015 15-Performance Engagement at Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater June 10 - 21 New York – February 3, 2015 — Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, beloved as one of the world’s most popular dance companies, will travel to 18 cities coast-to-coast presenting 80 performances, beginning tonight at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC. Hitting other major venues like The Fox Theatre in Atlanta, the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, and the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, CA, the tour culminates May 10th at the beautiful Prudential Hall of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark, where Ailey is the Principal Resident Affiliate. For tickets, visit www.njpac.org. Artistic Director Robert Battle also announced that, following the tour, the Company will return to Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater from June 10th to 21st for 15 performances, continuing a new tradition for the company by hosting a second annual New York City season. -

~Lagf8lu COMPANIES INC

October 2000 BAMcinematek 2000 Next Wave Festival Brooklyn Philharmonic Robert Frank. Laura. 1998 BAM Next Wave Festival sponsor: PHILIP MORRIS ~lAGf8lU COMPANIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Alan H. Fishman Chairman of the Board Chairman of the Campaign for BAM Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents A Magic Science: Celebrating Jimi Hendrix Running time: BAM Howard Gilman Opera House approximately October 20, 2000, at 8pm (gala performance) two hours with no October 21, 2000, at 7:30pm intermission With Medeski Martin & Wood The Gil Evans Orchestra under the direction of Miles Evans Vernon Reid Featuring Chris Whitley Marc Anthony Thompson Sandra St. Victor OJ Logic and Glenn McKay's Light Show Jonathan "Futz" Cappel stage Iighti ng Danny Kapilian producer The Next Wave Festival Gala is sponsored by Philip Morris Companies Inc. and Ql04.3, with support from Dan Klores Associates and Pine Ridge Wineries. Next Wave Music supported by The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc. 29 Original artwork by Glenn McKay· A Magic Science: Celebrating Jimi Hendrix Medeski Martin & Wood Vernon Reid guitars John Medeski keyboards Chris Whitley guitars Billy Martin drums and percussion Marc Anthony Thompson lead Yocals Chris Wood basses Sandra St. Victor lead Yocals DJ Logic turntables The Gil Evans Orchestra Gil Evans and Miles Evans horn arrangements Miles Evans band leader, trumpet David Bargeron trombone Glenn McKay projected light images Kenny Berger baritone saxophone, Patricia Fox stage manager bass clarinet Philip Harvey sound mix Hiram Bullock guitar Chris Hunter alto saxophone David Mann soprano and tenor saxophones, flute Badal Roy tablas 30 Producer's Note A Magic Science Experience '~ny claim to know where Jimi Hendrix might have taken his talents and interests had he lived is absurd. -

Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms On/Through the Twenty- First Century New York Commercial Stage

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty- First Century New York Commercial Stage Stefanie A. Jones The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2025 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ACTS OF PROVOCATION: POPULAR ANTIRACISMS ON/THROUGH THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY NEW YORK COMMERCIAL STAGE by STEFANIE A. JONES A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 S A Jones © 2017 STEFANIE A. JONES ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii S A Jones Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty-First Century New York Commercial Stage Stefanie A. Jones This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________ ____________________________________ Date David Savran Chair of Examining Committee _____________ ____________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Kandice Chuh Robert Reid-Pharr James Wilson THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii S A Jones ABSTRACT Acts of Provocation: Popular Antiracisms on/through the Twenty-First Century New York Commercial Stage by Stefanie A. Jones Advisor: David Savran This is an abolitionist feminist study of the role of liberalism in the twenty-first century political economy. -

Carl Hancock Rux

Carl Hancock Rux Carl Hancock Rux crosses the disciplines of poetry, theater, music, and literary fiction in order to achieve what one critic describes as a “dizzying oral artistry...unleashing a torrent of paper bag poetry and post modern Hip-Bop music; the ritualistic blues of self awakening.” A published poet, playwright, novelist and essayist, Mr. Rux is a recipient of the New York Foundation for the Arts Prize; NYFA Gregory Millard Playwright in Residence Fellow; National Endowment for the Arts/Theater Communications Group Playwright in Residence Fellow; Bessie Schomburg award; and the coveted CalArts/Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. Mr. Rux is the author of several books including his first collection of poetry, Pagan Operetta (Fly By Night/Autonomedia Press), for which he received the Village Voice Literary prize; the OBIE award winning play Talk (TCG Press), and the novel Asphalt (Atria/Simon & Schuster; Washington Sq. Press paperback). A multi-disciplinary artist, Mr. Rux's most recent opera, The Blackamoor Angel (music composed by Deirdre Murray, directed by Karin Coonrod) premiered at Bard College, during the summer of 2007. Rux has toured extensively throughout the U.S. and abroad with his own performance works, including The No Black Male Show, and Mycenean (BAM Next Wave 2006) as well as principal performer in Robert Wilson and Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon's musical adaptation of Gustave Flaubert's Temptation of St. Anthony, which had its world premiere at the Paris Opera Garnier. He has been commissioned to write and perform his text in collaboration with several dance companies, including the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Urban Bush Women, and Jane Comfort & Co., among others.