A Conductor's Guide to David Del Tredici's in Wartime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 8 Robert HELPS AMERICAN CLASSICS (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS Shall We Dance Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne Spectrum Concerts Berlin 8.559199 8 559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 2 Robert Helps (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS (1928-2001) Shall We Dance • Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne • The Darkened Valley (John Ireland) 1 Shall We Dance for Piano (1994) 11:09 Robert Helps was Professor of Music at the University of Minneapolis, and elsewhere. His later concerts included Piano Quartet for Piano, Violin, Viola and Cello (1997) 25:55 South Florida, Tampa, and the San Francisco memorial solo recitals of the music of renowned Conservatory of Music. He was a recipient of awards in American composer Roger Sessions at both Harvard and 2 I. Prelude 10:24 composition from the National Endowment for the Arts, Princeton Universities, an all-Ravel recital at Harvard, 3 II. Intermezzo 2:24 the Guggenheim, Ford, and many other foundations, and and a solo recital in Town Hall, NY. His final of a 1976 Academy Award from the Academy of Arts compositions include Eventually the Carousel Begins, for 4 III. Scherzo 3:02 and Letters. His orchestral piece Adagio for Orchestra, two pianos, A Mixture of Time for guitar and piano, which 5 IV. Postlude 8:12 which later became the middle movement of his had its première in San Francisco in June 1990 by Adam 6 V. Coda – The Players Gossip 1:53 Symphony No. 1, won a Fromm Foundation award and Holzman and the composer, The Altered Landscape was premièred by Leopold Stokowski and the Symphony (1992) for organ solo and Shall We Dance (1994) for 7 Postlude for Horn, Violin and Piano (1964) 9:11 of the Air (formerly the NBC Symphony) at the piano solo, Piano Trio No. -

EMILY DICKINSON's POETIC IMAGERY in 21ST-CENTURY SONGS by LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, and DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submit

EMILY DICKINSON’S POETIC IMAGERY IN 21ST-CENTURY SONGS BY LORI LAITMAN, JAKE HEGGIE, AND DARON HAGEN by Shin-Yeong Noh Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Andrew Mead, Research Director ______________________________________ Patricia Stiles, Chair ______________________________________ Gary Arvin ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart March 7, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Shin-Yeong Noh iii To My Husband, Youngbo, and My Son iv Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without many people who aided and supported me. I am grateful to all of my committee members for their advice and guidance. I am especially indebted to my research director, Dr. Andrew Mead, who provided me with immeasurable wisdom and encouragement. His inspiration has given me huge confidence in my study. I owe my gratitude to my teacher, committee chair, Prof. Patricia Stiles, who has been very careful and supportive of my voice, career goals, health, and everything. Her instructions on the expressive performance have inspired me to consider the relationship between music and text, and my interest in song interpretation resulted in this study. I am thankful to the publishers for giving me permission to use the scores. Especially, I must thank Lori Laitman, who offered me her latest versions of the songs with a very neat and clear copy. She is always prompt and nice to me. -

Alumnews2007

C o l l e g e o f L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f o f C a l i f o r n i a B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 7 1–2 Special Occasions Special Occasions CELEBRATIONS 2–4 Events, Visitors, Alumni n November 8, 2006, the department honored emeritus professor Andrew Imbrie in the year of his 85th birthday 4 Faculty Awards Owith a noon concert in Hertz Hall. Alumna Rae Imamura and world-famous Japanese pianist Aki Takahashi performed pieces by Imbrie, including the world premiere of a solo piano piece that 5–6 Faculty Update he wrote for his son, as well as compositions by former Imbrie Aki Takahashi performss in Hertz Hall student, alumna Hi Kyung Kim (professor of music at UC Santa to honor Andrew Imbrie. 7 Striggio Mass of 1567 Cruz), and composers Toru Takemitsu and Michio Mamiya, with whom Imbrie connected in “his Japan years.” The concert was followed by a lunch in Imbrie’s honor in Hertz Hall’s Green Room. 7–8 Retirements Andrew Imbrie was a distinguished and award-winning member of the Berkeley faculty from 1949 until his retirement in 1991. His works include five string quartets, three symphonies, numerous concerti, many works for chamber ensembles, solo instruments, piano, and chorus. His opera Angle of 8–9 In Memoriam Repose, based on Wallace Stegner’s book, was premeiered by the San Francisco Opera in 1976. -

ROBERT HELPS in Berlin Chamber Music with Piano

559696-97 bk Helps US 22/6/11 12:21 Page 20 Also available from Spectrum Concerts Berlin: AMERICAN CLASSICS ROBERT HELPS in Berlin Chamber Music with Piano Spectrum Concerts Berlin ATOS Trio Robert Helps, Piano 8.559199 2 CDs 8.559696-97 20 559696-97 bk Helps US 22/6/11 12:21 Page 2 CD 1 55:36 CD 2 62:13 Also available from Spectrum Concerts Berlin: 1 Postlude for Horn, Violin Trio I for Violin, Cello and Piano (1957) 14:36 and Piano (1964) 8:43 1 I. Mesto 5:37 2 II. Molto marcato 4:18 2 Fantasy for Violin and Piano (1963) 6:57 3 III. Maestoso 4:41 Quartet for Piano, Violin, Trio II for Violin, Cello and Piano (2000) 12:23 Viola and Cello (1997) 17:52 4 I. Duets: Allegro 3:06 5 3 I. Prelude 5:32 II. Horizons: Austere, but intense 6:47 6 4 II. Intermezzo (Flowing – Expressive – Sempre legato) 2:22 III. Toccata frustrata 2:30 5 III. Scherzo 3:19 7 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47): Six Lieder, Op. 71 6 IV. Postlude 4:38 No. 4: Schilflied (1842-47, arr. Helps 1988) 3:53 7 V. Coda – The Players Gossip (Allegro giocoso) 2:01 8 John Ireland (1879-1962): Love is a Sickness Full of Woes (1921, arr. Helps 1995) 2:59 8 Duo for Cello and Piano (1977) 8:10 9 Francis Poulenc (1899-1963): Quintet for Violin, Cello, Flute, Intermezzo in A flat major (1943) 4:18 Clarinet and Piano (1997) 13:54 Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938): 9 I. -

October 12, 7:30 Pm

GRIFFIN CONCERT HALL / UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS Featuring the music of Wilson, Dvorak, Persichetti, Sousa, Ravel/Frey, and Schwantner OCTOBER 12, 7:30 P.M. THE COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY WIND SYMPHONY PRESENTS: FIND YOUR STATE: State of Inspiration REBECCA PHILLIPS, Conductor ANDREW GILLESPIE, Graduate Student Conductor RICHARD FREY, Guest Conductor CORRY PETERSON, Guest Conductor Fanfare for Karel (2017) / DANA WILSON Serenade in d minor, op. 44 (1878) / ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Moderato, quasi Marcia Finale Symphony for Band (Symphony No. 6), op. 69 (1956) / VINCENT PERSICHETTI Adagio, Allegro Adagio sostenuto Allegretto Vivace Andrew Gillespie, graduate guest conductor Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (1923) / JOHN PHILIP SOUSA Corry Peterson, guest conductor, Director of Bands, Poudre High School Ma mére l’Oye (Mother Goose Suite) (1910) / MAURICE RAVEL trans. by Richard Frey Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (Pavane of Sleeping Beauty) Petit Poucet (Little Tom Thumb) Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes (Little Ugly Girl, Empress of the Pagodas) Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête (Conversation of Beauty and the Beast) Le jardin féerique (The Fairy Garden) Richard Frey, guest conductor From a Dark Millennium (1980) / JOSEPH SCHWANTNER The 2017-18 CSU Wind Symphony season highlights Colorado State University's commitment to inspiration, innovation, community, and collaboration. All of these ideals can clearly be connected by music, and the Wind Symphony begins the season by featuring works that have been inspired by other forms of art, including folk songs, hymns, fairy tales, and poems. We hope that you will join us to "Find Your State” at the UCA! NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Fanfare for Karel (2017) Dana Wilson Born: 4 February 1946, Lakewood, Ohio Duration: 2 minutes Born in Prague on August 7, 1921, Karel Jaroslav Husa was forced to abandon his engineering studies when Germany occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939 and closed all technical schools. -

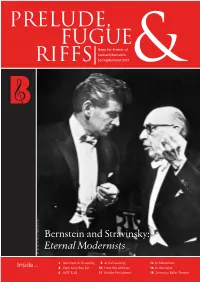

Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY of the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES COURTESY

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2021 COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC ARCHIVES Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists 2 Bernstein & Stravinsky 8 Artful Learning 12 In Memoriam Inside... 4 New Sony Box Set 10 From the Archives 14 In the News 6 MTT & LB 11 Mahler Remastered 16 American Ballet Theatre Bernstein and Stravinsky: Eternal Modernists by Hannah Edgar captivated.1 For the eternally young Bernstein, The Rite of Spring would concert program is worth forever represent youth—its super- ince when did a virus ever slow Lenny a thousand words—though lative joys and sorrows, but also its Sdown? Seems like he’s all around us, Leonard Bernstein rarely supreme messiness. Working with the and busier than ever. The new boxed Aprepared one without inaugural 1987 Schleswig-Holstein set from Sony is a magnificent way to the other. Exactly a year after Igor Music Festival Orchestra Academy, commemorate the 50th anniversary Stravinsky’s death on April 6, 1971, Bernstein’s training ground for young of Stravinsky’s death, and to marvel at Bernstein led a televised memorial musicians, he kicked off the orches- Bernstein’s brilliant evocations of those concert with the London Symphony tra’s first rehearsal of the Rite with his seminal works. We’re particularly happy Orchestra, delivering an eloquent usual directness. “The Rite of Spring to share a delightful reminiscence from eulogy to the late composer as part of is about sex,” he declared, to titillated Michael Tilson Thomas, describing the the broadcast. Most telling, however, whispers. “Think of the times we all joy, and occasionally maddening hilarity, are the sounds that filled the Royal experience during adolescence, when of sharing a piano keyboard with the Albert Hall’s high dome that day. -

Scrolls of Love Ruth and the Song of Songs Scrolls of Love

Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg Scrolls of Love ruth and the song of songs Scrolls of Love ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE i ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE ii Scrolls of Love reading ruth and the song of songs Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York / 2006 ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2006 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scrolls of love : reading Ruth and the Song of songs / edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2526-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2526-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Ruth—Criticism interpretation, etc. 2. Bible. O.T. Song of Solomon—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Hawkins, Peter S. II. Stahlberg, Lesleigh Cushing. BS1315.52.S37 2006 222Ј.3506—dc22 2006029474 Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 First edition ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iv For John Clayton (1943–2003), mentor and friend ................ -

PAX MUSICAMUSICA 2011 Touring Year • Client Tour Stories 2011 Highlights What’S Inside Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Classical Movements, Inc. PAXPAX MUSICAMUSICA 2011 Touring Year • Client Tour Stories 2011 Highlights What’s Inside Baltimore Symphony Orchestra ........... 9 202 Concerts Canterbury Youth Chorus ................. 15 Arranged College of William and Mary ............ 10 Worldwide Collège Vocal de Laval ...................... 11 Read more inside! Children’s Chorus of Sussex County ............................... 7 Dallas Symphony Orchestra Proud to Start and Chorus .................................... 9 Our 20th Year Drakensberg Boys’ Choir .................... 2 Eric Daniel Helms Classical Movements New Music Program ...................... 5 Rwas established in El Camino Youth Orchestra ................ 7 1992, originally Fairfield County Children’s Choir .......................... 15 operating as Blue George Washington University Choir .. 7 Heart Tours and Greater New Orleans providing exclusive Youth Orchestra ............................ 4 tours to Russia. Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra ............... 3 Ihlombe! South African Rapidly, more Choral Festival ............................. 14 countries were added, Marin Alsop (Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Music Director), David Los Angeles Children’s Choir ........... 15 attracting more and Rimelis (Composer), Dan Trahey (OrchKids Director of Artistic Melodia! South American Program Development) and Neeta Helms (Classical Movements Music Festival ................................ 6 more extraordinary President) at the premiere of Rimelis’ piece OrchKids Nation Minnesota Orchestra .......................... -

New Chamber & Solo Music

NWCR649 New Chamber & Solo Music David Del Tredici, Robert Helps, Jan Radzynski, Tison Street 7. III - Allegro Minacciando (…Diabolique) ......... (1:25) 8. IV - Largo ............................................................ (4:37) David Del Tredici, piano Jan Radzynski 9. String Quartet (1978) ........................................... (12:00) The Aviv String Quartet: Hagai Shaham, violin; John McGross, violin; Yariv Aloni, viola; Zvi Plesser, cello 10. Canto (1981) ....................................................... (10:18) Arnon Erez, piano Five Duets (1982) 11. I – Risoluto .......................................................... (1:25) 12. II – Allegro .......................................................... (1:05) 13. III – Allegretto burlesco ...................................... (1:19) 14. IV – Remembering Sepharad .............................. (2:51) 15. V – Agitato .......................................................... (2:25) Maya Beiser, Zvi Plesser, cellos Tison Street Robert Helps 16. Trio (1963) .......................................................... (9:38) 1. Hommage à Fauré (1972) ................................... (3:56) Members of Spectrum Ensemble Berlin: Per Sporrong, violin; Brett Dean, viola; Frank Dodge, cello 2. Hommage à Rachmaninov (1972) ....................... (2:17) Robert Helps 3. Hommage à Ravel (1972) ................................... (4:30) Robert Helps, piano 17. Nocturne (1960) .................................................. (7:42) Members of Spectrum Ensemble Berlin Mi-Kyung -

American Mavericks Festival

VISIONARIES PIONEERS ICONOCLASTS A LOOK AT 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES, FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY EDITED BY SUSAN KEY AND LARRY ROTHE PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNIVERSITY OF CaLIFORNIA PRESS The San Francisco Symphony TO PHYLLIS WAttIs— San Francisco, California FRIEND OF THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, CHAMPION OF NEW AND UNUSUAL MUSIC, All inquiries about the sales and distribution of this volume should be directed to the University of California Press. BENEFACTOR OF THE AMERICAN MAVERICKS FESTIVAL, FREE SPIRIT, CATALYST, AND MUSE. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England ©2001 by The San Francisco Symphony ISBN 0-520-23304-2 (cloth) Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI / NISO Z390.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Printed in Canada Designed by i4 Design, Sausalito, California Back cover: Detail from score of Earle Brown’s Cross Sections and Color Fields. 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Contents vii From the Editors When Michael Tilson Thomas announced that he intended to devote three weeks in June 2000 to a survey of some of the 20th century’s most radical American composers, those of us associated with the San Francisco Symphony held our breaths. The Symphony has never apologized for its commitment to new music, but American orchestras have to deal with economic realities. For the San Francisco Symphony, as for its siblings across the country, the guiding principle of programming has always been balance. -

Chana Kronfeld's CV

1 Kronfeld/CV CURRICULUM VITAE CHANA KRONFELD Professor of Modern Hebrew, Yiddish and Comparative Literature Department of Near Eastern Studies, Department of Comparative Literature and the Designated Emphasis in Jewish Studies 250 Barrows Hall University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 #1940 Home phone & fax (510) 845-8022; cell (510) 388-5714 [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. 1983 University of California, Berkeley, Comparative Literature, Dissertation: “Aspects of Poetic Metaphor” MA 1977 University of California, Berkeley, Comparative Literature (with distinction) BA 1971 Tel Aviv University, Poetics and Comparative Literature; English (Summa cum laude) PRINCIPAL ACADEMIC INTERESTS: Modernism in Hebrew, Yiddish and English poetry, intertextuality, translation studies, theory of metaphor, literary historiography, stylistics and ideology, gender studies, political poetry, marginality and minor literatures, literature & linguistics, negotiating theory and close reading. HONORS AND FELLOWSHIPS: § 2016 – Finalist, Northern California Book Award (for The Full Severity of Compassion: The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai) § 2015 - Diller Grant for Summer Research, Center for Jewish Studies, University of California, Berkeley § 2014-15 Mellon Project Grant, University of California, Berkeley § 2014 - “The Berkeley School of Jewish Literature: Conference in Honor of Chana Kronfeld,” Graduate Theological Union and UC Berkeley, March 9, 2014 and Festschrift: The Journal of Jewish Identities, special issue: The Berkeley School of Jewish -

31 July — 4 August 1982

Tang °d 31 July — 4 August 1982 Tanglewood The Berkshire Music Center Gunther Schuller, Artistic Director (on sabbatical) Maurice Abravanel, Acting Artistic Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus John Oliver, Head of Vocal Music Activities Gustav Meier, Head Coach, Conducting Activities Gilbert Kalish, Head of Chamber Music Activities Dennis Helmrich, Head Vocal Coach Daniel R. Gustin, Administrative Director Richard Ortner, Administrator Jacquelyn R. Donnelly, Administrative Assistant Harry Shapiro, Orchestra Manager James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Jean Scarrow, Vocal Activities Coordinator John Newton, Sound Engineer Marshall Burlingame, Orchestra Librarian Douglas Whitaker, Stage Manager Carol Woodworth, Secretary to the Faculty Karen Leopardi, Secretary Monica Schmelzinger, Secretary Elizabeth Burnett, Librarian Theodora Drapos, Assistant Librarian Festival of Contemporary Music presented in cooperation with The Fromm Music Foundation at Harvard Fellowship Program Contemporary Music Activities Luciano Berio, Acting Director & Composer-in-Residence Theodore Antoniou, Assistant Director Arthur Berger, Robert Morris, William Thomas McKinley, Yehudi Wyner, Guest Teachers The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music and sponsored by the Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Thomas W. Morris, General Manager References furnished on request Aspen Music School and Peter Duchin Zubin Mehta Festival Bill Evans Milwaukee Symphony Dickran Atamian