Telling the Mythology: from Hesiod to the Fifth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2009 A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. "A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' 'Orphic' Creation of Mankind." American Journal of Philology 130, no. 4 (2009): 511-532. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III “A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' ‘Orphic’ Creation of Mankind” American Journal of Philology 130 (2009), pp. 511–532. A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' Creation of Mankind Olympiodorus' recounting (In Plat. Phaed. I.3-6) of the Titan's dismemberment of Dionysus and the subsequent creation of humankind has served for over a century as the linchpin of the reconstructions of the supposed Orphic doctrine of original sin. From Comparetti's first statement of the idea in his 1879 discussion of the gold tablets from Thurii, Olympiodorus' brief testimony has been the -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

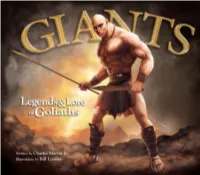

Giants: Legends & Lore of Goliaths

PERHAPS MYTHOLOGY CONTAINS MORE TRUTH THAN WE REALIZE! The word “myth” has come to mean “fiction” in our minds, and so some people take Bible accounts, Aesop’s fables, and Greek myths and place them all in the same category. But what if some of the old legends are true? Rather than dismiss these narratives, perhaps we should investigate them. In this case, the world is filled with giant legends that speak of heroes and wars. In this highly engaging book of giants you will discover ? Unique glimpses into the ancient accounts of giants from around the world @ What does the Bible say about giants? ? Full-color artistry developed in an interactive format with fold outs and flaps, booklets, and more! @ A spectacular center spread stretching 4-feet across! It is fascinating that the ancient world agreed on many aspects of the Martin Bible, one of these being that early in the history of mankind, a race of violent, yet intelligent giants walked the earth, were destroyed by the Flood. Through historical records, the pre-Flood and post-Flood worlds are reconstructed, with giants re-emerging in and around Israel, and you’ll see one more reason that the Bible can be trusted. RELIGION/Biblical Studies/General JUVENILE NONFICTION/Religious/ Christian/General $18.99 U.S. ISBN-13: 978-0-89051-864-9 EAN First printing: June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Master Books. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used Odysseus Blinds Polyphemus or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. -

Homer the Iliad

1 Homer The Iliad Translated by Ian Johnston Open access: http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/homer/iliadtofc.html 2010 [Selections] CONTENTS I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS 2 II AGAMEMNON'S DREAM AND THE CATALOGUE OF SHIPS 5 III PARIS, MENELAUS, AND HELEN 6 IV THE ARMIES CLASH 6 V DIOMEDES GOES TO BATTLE 6 VI HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE 6 VII HECTOR AND AJAX 6 VIII THE TROJANS HAVE SUCCESS 6 IX PEACE OFFERINGS TO ACHILLES 6 X A NIGHT RAID 10 XI THE ACHAEANS FACE DISASTER 10 XII THE FIGHT AT THE BARRICADE 11 XIII THE TROJANS ATTACK THE SHIPS 11 XIV ZEUS DECEIVED 11 XV THE BATTLE AT THE SHIPS 11 XVI PATROCLUS FIGHTS AND DIES 11 XVII THE FIGHT OVER PATROCLUS 12 XVIII THE ARMS OF ACHILLES 12 XIX ACHILLES AND AGAMEMNON 16 XX ACHILLES RETURNS TO BATTLE 16 XXI ACHILLES FIGHTS THE RIVER 17 XXII THE DEATH OF HECTOR 17 XXIII THE FUNERAL GAMES FOR PATROCLUS 20 XXIV ACHILLES AND PRIAM 20 I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS [The invocation to the Muse; Agamemnon insults Apollo; Apollo sends the plague onto the army; the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon; Calchas indicates what must be done to appease Apollo; Agamemnon takes Briseis from Achilles; Achilles prays to Thetis for revenge; Achilles meets Thetis; Chryseis is returned to her father; Thetis visits Zeus; the gods con-verse about the matter on Olympus; the banquet of the gods] Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus. -

Homer's Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon

Homer’s Use of Myth Françoise Létoublon Epic and Mythology The Homeric Epics are probably the oldest Greek literary texts that we have,1 and their subject is select episodes from the Trojan War. The Iliad deals with a short period in the tenth year of the war;2 the Odyssey is set in the period covered by Odysseus’ return from the war to his homeland of Ithaca, beginning with his departure from Calypso’s island after a 7-year stay. The Trojan War was actually the material for a large body of legend that formed a major part of Greek myth (see Introduction). But the narrative itself cannot be taken as a mythographic one, unlike the narrative of Hesiod (see ch. 1.3) - its purpose is not to narrate myth. Epic and myth may be closely linked, but they are not identical (see Introduction), and the distance between the two poses a particular difficulty for us as we try to negotiate the the mythological material that the narrative on the one hand tells and on the other hand only alludes to. Allusion will become a key term as we progress. The Trojan War, as a whole then, was the material dealt with in the collection of epics known as the ‘Epic Cycle’, but which the Iliad and Odyssey allude to. The Epic Cycle however does not survive except for a few fragments and short summaries by a late author, but it was an important source for classical tragedy, and for later epics that aimed to fill in the gaps left by Homer, whether in Greek - the Posthomerica of Quintus of Smyrna (maybe 3 c AD), and the Capture of Troy of Tryphiodoros (3 c AD) - or in Latin - Virgil’s Aeneid (1 c BC), or Ovid’s ‘Iliad’ in the Metamorphoses (1 c AD). -

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus' Europia

Gaia Revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce archaïque 22-23 | 2020 Varia The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia La généalogie de Dionysos: Bacchylide 19 et l’Europia d’Eumélos Marios Skempis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/gaia/512 ISSN: 2275-4776 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version ISBN: 978-2-37747-199-7 ISSN: 1287-3349 Electronic reference Marios Skempis, « The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia », Gaia [Online], 22-23 | 2020, Online since 30 June 2020, connection on 17 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/gaia/512 This text was automatically generated on 17 July 2020. Gaia. Revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce archaïque The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia 1 The Genealogy of Dionysus: Bacchylides 19 and Eumelus’ Europia La généalogie de Dionysos: Bacchylide 19 et l’Europia d’Eumélos Marios Skempis 1 Bacchylides’ relation to the Epic Cycle is an issue under-appreciated in the study of classical scholarship, the more so since modern Standardwerke such as Martin West’s The Epic Cycle and Marco Fantuzzi and Christos Tsagalis’ The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Reception: A Companion are unwilling to engage in discussions about the Cycle’s impact on this poet.1 A look at the surviving Dithyrambs in particular shows that Bacchylides appropriates the Epic Cycle more thoroughly than one expects: Bacchylides 15 reworks the Cypria’s Request for Helen’s Return (arg. 10 W); Bacchylides 16 alludes to Creophylus’ Sack of Oechalia; Bacchylides 17 and 18 are instantiations of mythical episodes plausibly excerpted from an archaic Theseid; Bacchylides 19 opens and ends its mythical section with a circular mannerism that echoes the Thebaid’s incipit (fr. -

A New Companion to the Greek Epic Cycle

Histos 10 (2016) cxvi–cxxiii REVIEW A NEW COMPANION TO THE GREEK EPIC CYCLE Marco Fantuzzi and Christos Tsagalis, edd., The Greek Epic Cycle and its Ancient Reception: A Companion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. Pp. xiii + 678. Hardback, $195.00. ISBN 978-1-107-01259-2. nough and too much has been written about the Epic Cycle’, wrote T. W. Allen in 1908, but more recent scholarship has not been dis- ‘E suaded from tackling the subject afresh. We now have three editions of the fragments and testimonia, by Bernabé, Davies, and West; the short but useful survey by Davies (1989) was followed by a more ambitious and heretical analysis by Burgess (2001); West has produced a commentary on the Trojan epics (with valuable prolegomena which look more widely), and Davies a typ- ically learned one on the less well-attested Theban series. But all these contri- butions are dwarfed by the book under review, containing a substantial intro- duction and thirty-two essays which occupy well over 600 pages, with a forty- five-page bibliography.1 This is not a volume in the Cambridge Companion series, but more advanced and in grander format.2 It is full of useful material, though inevitably there is a lot of repetition and despite its scale it cannot be regarded as comprehensive. Nevertheless, there is much food for thought. The book falls into three parts. Part I consists of ten general essays (‘Ap- proaches to the Epic Cycle’); part II contains eleven specific studies (one on ‘Theogony and Titanomachy’, plus an essay on each of the attested Theban and Trojan epics); part III deals with ancient reception, mostly in specific genres or authors. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

Greek Mythology / Apollodorus; Translated by Robin Hard

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Robin Hard 1997 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published as a World’s Classics paperback 1997 Reissued as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Apollodorus. [Bibliotheca. English] The library of Greek mythology / Apollodorus; translated by Robin Hard.