1 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tmobilewea-2.Pdf

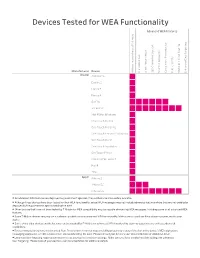

Devices Tested for WEA Functionality Advanced WEA Features s t x e t A n g E o n g t i i r W n t t i o a c e t i t p s g s n n r p e e a e o a u T g i b s T l S a t - e e s a r a u r o v c k v e y g i e P o r t n t n e i t G L c e e c a L n f a s d e d L r e a e e r e n l r r a h S c r a b o s h P c n i t u a i e C t l a c n k t e r l b 0 h a c n a e i b l u n 6 Manufacturer Device l p o t A C A 3 S C P S E Alcatel A30 Fierce Evolve 2 Fierce 2 Fierce 4 Go Flip GO FLIP3 Idol 4S for Windows One Touch Evolve One Touch Fierce XL One Touch Fierce XL Windows One Touch Pixi 7 One Touch Pop Astro OneTouch Fierce ONETOUCH Fierce 4 Pixi 4 TRU Apple iPhone 5 iPhone 5C iPhone 5S iPhone 6 • As advanced WEA features are deployed by government agencies, they will become more widely available. • Although these devices have been tested for their WEA functionality, actual WEA messages may not include advanced features where they are not enabled or deployed by the government agency sending the alert. -

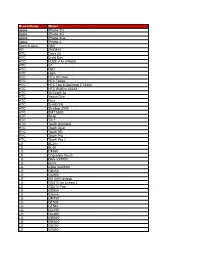

Factory Model Device Model

Factory Model Device Model Acer A1-713 acer_aprilia Acer A1-811 mango Acer A1-830 ducati Acer A3-A10 G1EA3 Acer A3-A10 mtk6589_e_lca Acer A3-A10 zara Acer A3-A20 acer_harley Acer A3-A20FHD acer_harleyfhd Acer Acer E320-orange C6 Acer Aspire A3 V7 Acer AT390 T2 Acer B1-723 oban Acer B1-730 EverFancy D40 Acer B1-730 vespatn Acer CloudMobile S500 a9 Acer DA220HQL lenovo72_we_jb3 Acer DA222HQL N451 Acer DA222HQLA A66 Acer DA222HQLA Flare S3 Power Acer DA226HQ tianyu72_w_hz_kk Acer E330 C7 Acer E330 GT-N7105T Acer E330 STUDIO XL Acer E350 C8n Acer E350 wiko Acer G100W maya Acer G1-715 A510s Acer G1-715 e1808_v75_hjy1_5640_maxwest Acer Icona One 7 vespa Acer Iconia One 7 AT1G* Acer Iconia One 7 G1-725 Acer Iconia One 7 m72_emmc_s6_pcb22_1024_8g1g_fuyin Acer Iconia One 7 vespa2 Acer Iconia One 8 vespa8 Acer Iconia Tab 7 acer_apriliahd Acer Iconia Tab 8 ducati2fhd Acer Iconia Tab 8 ducati2hd Acer Iconia Tab 8 ducati2hd3g Acer Iconia Tab 8 Modelo II - Professor Acer Iconia Tab A100 (VanGogh) vangogh Acer Iconia Tab A200 s7503 Acer Iconia Tab A200 SM-N9006 Acer Iconia Tab A501 ELUGA_Mark Acer Iconia Tab A501 picasso Acer Iconia Tab A510 myPhone Acer Iconia Tab A510 picasso_m Acer Iconia Tab A510 ZUUM_M50 Acer Iconia Tab A701 picasso_mf Acer Iconia Tab A701 Revo_HD2 Acer Iconia TalkTab 7 acer_a1_724 Acer Iconia TalkTab 7 AG CHROME ULTRA Acer Liquid a1 Acer Liquid C1 I1 Acer Liquid C1 l3365 Acer Liquid E1 C10 Acer Liquid E2 C11 Acer Liquid E3 acer_e3 Acer Liquid E3 acer_e3n Acer Liquid E3 LS900 Acer Liquid E3 Quasar Acer Liquid E600 e600 Acer Liquid -

Case 5:18-Cv-06739-VKD Document 27 Filed 07/02/18 Page 1 of 11

Case 5:18-cv-06739-VKD Document 27 Filed 07/02/18 Page 1 of 11 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION § UNILOC USA, INC. and § UNILOC LUXEMBOURG, S.A., § Civil Action No. 3:18-cv-00560-DCG § Plaintiffs, § § v. § PATENT CASE § LG ELECTRONICS U.S.A., INC., § LG ELECTRONICS MOBILECOMM § U.S.A. INC. and § LG ELECTRONICS, INC., § § Defendant. § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED § FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiffs, Uniloc USA, Inc. (“Uniloc USA”) and Uniloc Luxembourg, S.A. (“Uniloc Luxembourg”) (together, “Uniloc”), for their First Amended Complaint against defendant, LG Electronics U.S.A. (“LGE”), Inc., LG Electronics Mobilecomm U.S.A., Inc., and LG Electronics, Inc., (“LG Korea”) (together “LG”), allege as follows:1 THE PARTIES 1. Uniloc USA is a Texas corporation having a principal place of business at Legacy Town Center I, Suite 380, 7160 Dallas Parkway, Plano Texas 75024. Uniloc USA also maintains a place of business at 102 N. College, Suite 603, Tyler, Texas 75702. 1 An amended complaint supersedes the original complaint and renders it of no legal effect, King v. Dogan, 31 F.3d 344. 346 (5th Cir. 1994), rendering a motion to dismiss the original complaint moot. See, e.g., Mangum v. United Parcel Services, No. 3:09-cv-0385, 2009 WL 2700217 (N.D. Tex. Aug. 26, 2009). 2988606.v1 Case 5:18-cv-06739-VKD Document 27 Filed 07/02/18 Page 2 of 11 2. Uniloc Luxembourg is a Luxembourg public limited liability company having a principal place of business at 15, Rue Edward Steichen, 4th Floor, L-2540, Luxembourg (R.C.S. -

Apple Apple Apple $44.00 $220.00 $335.00

Price valid on product shipped between November 1st and November 30th and is subject to approval. Find My iPhone/Find My iPad must be removed. Page 1 November 2014 Apple Apple Apple iPad 16GB $44.00 iPad 4th Gen 4G 32GB $220.00 iPad Air 4G 64GB $335.00 iPad 32GB $48.00 iPad 4th Gen 4G 64GB $240.00 iPad Air 4G 128GB $365.00 iPhone 4GB iPad 64GB iPad 4th Gen 4G 128GB $51.00 $260.00 1st Gen $2.00 iPhone 8GB iPad 16GB 3G iPad Mini 16GB $50.00 $110.00 1st Gen $3.00 iPhone 16GB iPad 32GB 3G iPad Mini 32GB $52.00 $140.00 1st Gen $5.00 iPad 64GB 3G $55.00 iPad Mini 64GB $175.00 iPhone 3G 8GB $5.00 iPad 2 16GB $100.00 iPad Mini 4G 16GB $130.00 iPhone 3G 16GB $6.00 iPad 2 32GB $110.00 iPad Mini 4G 32GB $150.00 iPhone 3G S 8GB $8.00 iPad 2 64GB $125.00 iPad Mini 4G 64GB $175.00 iPhone 3G S 16GB $11.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 2 16GB 3G iPhone 3G S 32GB $105.00 16GB $190.00 $13.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 2 32GB 3G iPhone 4 8GB GSM $115.00 32GB $220.00 $34.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 2 64GB 3G iPhone 4 8GB Sprint $130.00 64GB $250.00 $23.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 3rd Gen 16GB iPhone 4 8GB Verizon $130.00 128GB $290.00 $28.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 3rd Gen 32GB iPhone 4 16GB GSM $145.00 4G 16GB $200.00 $38.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 3rd Gen 64GB iPhone 4 16GB Verizon $175.00 4G 32GB $230.00 $40.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 3rd Gen 4G 16GB iPhone 4 32GB GSM $135.00 4G 64GB $260.00 $41.00 iPad Mini 2nd Gen Retina iPad 3rd Gen 4G 32GB iPhone 4 32GB Verizon $165.00 4G 128GB $310.00 $42.00 iPad 3rd Gen 4G 64GB $185.00 -

English-Basic-Deductible-Tool.Pdf

T-Mobile® Deductible and Fee Schedule Alcatel Tier BlackBerry Tier HTC Tier 3T 8 7100T, 7105T 10 665 7230, 7290 Flyer 768 8120, 8520 myTouch 2 A30 9780 Bold myTouch 4G Slide 3 Aspire Classic One Evolve Curve Sensation 4G Fierce XL Windows Phone 8X Fierce, Fierce 2, Fierce 4 9700 Bold 1 GO FLIP, GO FLIP 3 9810, 9900 3 JOY TAB Q10 Huawei Tier LINKZONE Z10 Pixi 7 Comet POP 7 Priv 4 Prism, Prism II Sonic 4G POP Astro 1 REVVL Coolpad Tier Summit Tap Soul Catalyst webConnect JOY TAB Kids 2 Defiant Rogue 1 myTouch 2 IDOL 4S 3 Snap Surf S7 PRO 3 Apple Tier life 2 iPad One M9 KonnectONE Tier iPad 7th Gen iPad Air 2 Dell Tier Moxee Signal 1 iPad Mini, iPad Mini 2, iPad Mini 4 Streak 7 2 iPhone 4, iPhone 4s iPhone 5, iPhone 5c, iPhone 5s 3 Kyocera Tier Ericsson Tier iPhone 6s Hydro WAVE iPhone SE World 1 1 Watch Series 3 Rally Watch Series 5 Garmin Tier DuraForce PRO, DuraForceXD 3 iPad Air Garminfone 3 iPad Mini 3 LG Tier GEOTAB Tier iPad Pro 9.7 450 iPhone 6 4 GO8 Aristo iPhone 6s Plus 1 iPhone 7, iPhone 7 Plus SyncUP FLEET Aristo 2 PLUS Watch Series 4 Aristo 4+ Google Tier dLite iPad Pro 10.5-inch GS170 1 Pixel 3a iPad Pro 11-inch 3 K7, K10 iPad Pro 12.9-inch Pixel 3a XL K20 Plus iPhone 6 Plus Pixel 3 Leon iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus Pixel 3 XL 4 Optimus L90 iPhone X 5 Sentio iPhone XR Pixel 4 iPhone XS, iPhone XS MAX Pixel 4 XL 5 DoublePlay iPhone 11 G Pad F 8.0 iPhone 11 Pro, iPhone 11 Pro Max HTC Tier G Pad X2 8.0, G Pad X2 8.0 Plus Watch Nike+ Series 3 G Pad X 8.0 Desire 1 G Stylo ASUS Tier Amaze 4G G2 Dash 3G G2x Google Nexus 7 2 K30 G2 2 HD2, HD7 K40 life Lion myTouch 3G 1.2, myTouch 3G slide myTouch 2 myTouch 4G Optimus F3, F3Q, F6, L9, T One M9 Stylo 2 PLUS, Stylo 3 PLUS One S Stylo 4 Radar 4G Stylo 5 Shadow V20 Wildfire S Please note: If you switch your device to one that is classified in another tier, the monthly charge for your new tier will be reflected on your T-Mobile bill. -

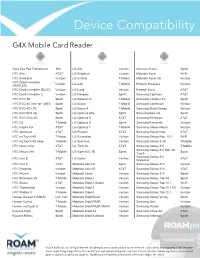

Device Compaibility List

Device Compatibility G4X Mobile Card Reader Asus Eee Pad Transformer N/A LG Ally Verizon Motorola Photon Sprint HTC Aria AT&T LG Enlighten Verizon Motorola Xoom Wi-Fi HTC Droid Eris Verizon LG G-Slate T-Mobile Motorola Xoom 4G Verizon HTC Droid Incredible Verizon LG G2X T-Mobile Pantech Breakout Verizon (AMOLED) HTC Droid Incredible (SLCD) Verizon LG Lucid Verizon Pantech Burst AT&T HTC Droid Incredible 2 Verizon LG Marquee Sprint Samsung Captivate AT&T HTC EVO 3D Sprint LG Mytouch Q T-Mobile Samsung Conquer 4G Sprint HTC EVO 4G (h/w ver. 0003) Sprint LG Nexus T-Mobile Samsung Continuum Verizon HTC EVO 4G LTE Sprint LG Nexus 4 T-Mobile Samsung Droid Charge Verizon HTC EVO Shift 4G Sprint LG Optimus Elite Sprint Samsung Epic 4G Sprint HTC EVO View 4G Sprint LG Optimus G AT&T Samsung Exhilarate AT&T HTC G2 T-Mobile LG Optimus S Sprint Samsung Fascinate Verizon HTC Inspire 4G AT&T LG Optimus T T-Mobile Samsung Galaxy Nexus Verizon HTC Jetstream AT&T LG Phoenix AT&T Samsung Galaxy Note AT&T HTC myTouch 4G T-Mobile LG Revolution Verizon Samsung Galaxy Note 10.1 Wi-Fi HTC myTouch 4G Slide T-Mobile LG Spectrum Verizon Samsung Galaxy S 4G T-Mobile HTC Nexus One AT&T LG Thrill 4G AT&T Samsung Galaxy S II T-Mobile Samsung Galaxy S II Epic 4G HTC Nexus One T-Mobile LG Viper 4G LTE Sprint Sprint Touch Samsung Galaxy S II HTC One S AT&T LG Vortex Verizon AT&T Skyrocket HTC One X AT&T Motorola Admiral Sprint Samsung Galaxy S III Verizon HTC Rezound Verizon Motorola Atrix 4G AT&T Samsung Galaxy S III AT&T HTC Rhyme Verizon Motorola Citrus Verizon Samsung Galaxy S III Sprint HTC Sensation 4G T-Mobile Motorola Droid 2 Verizon Samsung Galaxy Tab 3G Sprint HTC Status AT&T Motorola Droid 2 Global Verizon Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 Wi-Fi HTC Thunderbolt Verizon Motorola Droid 3 Verizon Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 4G Verizon HTC Wildfire S T-Mobile Motorola Droid 4 Verizon Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1 Verizon Huawei Ascend II (M865) U.S. -

Factory Model Device Model

Factory Model Device Model Acer A1-713 acer_aprilia Acer A1-830 Avvio_753 Acer A1-830 X958E Acer A3-A20 8675 Acer Acer E320-orange C6 Acer Acer E320-orange Oysters T72MR 3G Acer AT390 QMobile i10 Acer AT390 T2 Acer AT390 Xiaomi Acer B1-723 oban Acer B1-730 a29 Acer B1-820 i-mobile2.8 Acer CloudMobile S500 a9 Acer DA220HQL gilda_p8081 Acer DA226HQ sm618_w_ztc_72lca Acer E120 K2 Acer E310 lava75_cu_jb Acer E330 A37 Acer E330 C7 Acer E330 G910 Acer E330 msm8x25q_d5 Acer E330 Z50_Nova Acer E350 C8n Acer G100W F13 Acer Iconia Tab 7 acer_apriliahd Acer Iconia Tab A211 g12refM805 Acer Iconia Tab A211 MYPHONE_AGUA_OCEAN_MINI Acer Iconia Tab A501 E353I Acer Iconia Tab A510 K235 Acer Iconia TalkTab 7 acer_a1_724 Acer Iconia TalkTab 7 d3268_ctp_q_mobile Acer Liquid a1 Acer Liquid C1 I1 Acer Liquid C1 s620_f_h1_trx_j401_ec Acer Liquid E1 C10 Acer Liquid E2 C11 Acer Liquid E3 acer_e3 Acer Liquid E3 acer_e3n Acer Liquid E3 D7.2 3G Acer Liquid E3 hedy89_we_jb2 Acer Liquid E3 SOLO Acer Liquid E600 e600 Acer Liquid E600 S5J Acer Liquid E600 z3368 Acer Liquid E700 acer_e39 Acer Liquid Gallant E350 C8 Acer Liquid Jade acer_S55 Acer Liquid Jade S acer_S56 Acer Liquid Jade Z ABCD Acer Liquid Jade Z acer_S57 Acer Liquid Jade Z k002_gfen Acer Liquid Jade Z mobiistar BUDDY Acer Liquid Mini Bmobile.AX800 Acer Liquid Mini C4R Acer Liquid S1 a10 Acer Liquid S2 a12 Acer Liquid S2 B706 Acer Liquid S3 FIREFLY_S10DUAL Acer Liquid S3 s3 Acer Liquid X2 acer_S59 Acer Liquid X2 g517_d1e_less26 Acer Liquid Z200 A1000s Acer Liquid Z200 acer_z200 Acer Liquid Z200 s9201b Acer -

LG Lancerer to Nye Optimus Smartphones Med Android 2.2

2010-09-17 11:33 CEST LG lancerer to nye Optimus smartphones med Android 2.2 Optimus One og Optimus Chic har en rigtig god ydelse, en lokalt tilpasset App Advisor-applikation og de seneste mobiltjenester fra Google – alt i et stilrent design LG Electronics (LG) lancer to nye mobiltelefoner i Optimus-serien: LG Optimus One og LG Optimus Chic. Med operativsystemet Android 2.2 (Froyo) og optimering til Google Mobile Services tilbyder telefonerne en ultimativ smartphone-oplevelse, samtidig med at de med deres brugervenlighed er det ideelle valg for det voksende antal brugere, som står over for at løbe deres første smartphone. LG Optimus One og LG Optimus Chic er nogle af de første telefoner, som lanceres med Android 2.2, den seneste version af Android-platformen som giver 2-3 gange hurtigere websurfing og downloading af websider samt op til 5 gange hurtigere håndtering af tunge applikationer og multitasking. Telefonerne har via Android 2.2 også øget understøttelse af Exchange, hvilket giver erhvervskunder mulighed for nemt at synkronisere deres Outlook- kalender og e-mail. Optimus One og Optimus Chic giver mulighed for at oprette WiFi hotspots for nem deling af en 3G-opkobling. Telefonerne er optimeret til populære mobiltjenester fra Google, som f.eks. Google Voice Search™, Google Voice Action™, Google Goggles™, Google Shopper™ og Google Maps™ with Navigation. Desuden er der adgang til Android Market med mere end 80.000 spændende Android-applikationer. Kundeundersøgelser viser, at førstegangskøbere af smartphones ønsker at kunne søge efter informationer og bruge applikationstjenester, som forenkler brugervenligheden. LG Optimus One og Optimus Chic er udviklet på baggrund af disse ønsker. -

BT IOP Status Report (20110307)

Brand Name Model Apple iPhone 2G Apple iPhone 3G Apple iPhone 3Gs Apple iPhone 4 Garmin asus G60 HP iPAD912 HTC Dash 3G HTC Droid Eris HTC FUZE (TM ) P4600 HTC G1 HTC HD2 HTC Hero HTC HTC HD mini HTC HTC Tattoo HTC HTC Touch Diamond 2 T5353 HTC HTC Wildfire A3333 HTC MyTouch 3g HTC Nexus One HTC Pure HTC SHADOW HTC Shadow 2009 HTC SMT 5800 HTC Snap HTC Tilt 2 HTC Touch Diamond HTC Touch Dual HTC Touch HD HTC Touch Pro HTC Touch Pro 2 LG BL20v LG BL40 LG CF360 LG Chocolate Touch LG Dare VX9700 LG enV3 LG eXpo (GW820) LG GB250 LG GC900 LG GD 580 Lollipop LG GD310 Ice Cream 2 LG GD510 Pop LG GD900 LG Glance LG GM750 LG GT505 LG GT540 LG GU230 LG GU285 LG GW520 LG GW620 LG GX200 LG GX500 LG INCITE LG KC910 LG KM555 LG KM900 LG KP275 LG KP500 LG KS360 LG Lotus LX600 LG LX290 LG LX370 LG Neon (TM ) GT365 LG Rumor 2 LG Scoop / AX-260 LG Shine 2 LG Shine II GD710 AT&T LG Shine KE970 LG Versa LG Voyager VX10000 LG VX5500 LG VX8360 LG VX8610 LG Xenon (TM ) GR500 LG LX400 Moto Backflip ME600 Moto EM35 Moto Z9N Motorola Cliq Motorola Clutch (i465) Motorola Droid Motorola E1 Motorola E1070 Motorola E398 Motorola E8 Motorola EM30 Motorola i365 Motorola i576 Motorola i776 Motorola I9 Motorola K3 Motorola Karma QA1 Motorola MOTO (TM ) Z9 Motorola Q11 Motorola Q9H Motorola RAZR V3 Motorola RAZR V3xx Pink Motorola RAZR2 V9 Motorola Rival Motorola SLVR L72 Motorola U9 Motorola V1100 Motorola V360 Motorola V365 Motorola V3i Motorola V3x Motorola V500 Motorola V550 Motorola V551 Motorola V6 Motorola V750 Motorola V80 Motorola V860 Motorola V9 Motorola V950 -

English-P360-Deductible-Tool.Pdf

T-Mobile® Deductible and Fee Schedule Alcatel Tier BlackBerry Tier Huawei Tier 3T 8 9810, 9900 Comet 665 Q10 3 Prism, Prism II 768 Z10 Sonic 4G A30 Summit 1 Priv 4 Aspire Tap Evolve webConnect Fierce XL Coolpad Tier Fierce, Fierce 2, Fierce 4 1 Catalyst myTouch 2 GO FLIP Defiant LINKZONE S7 PRO 3 Pixi 7 Rogue 1 POP 7 Snap POP Astro Surf Kyocera Tier REVVL REVVL Plus 2 Soul Hydro WAVE 1 Rally IDOL 4S 3 Dell Tier Streak 7 2 DuraForce PRO, DuraForceXD 3 Apple Tier Ericsson Tier iPad LG Tier World 1 iPad Air 2 450 iPad Mini, iPad Mini 2, iPad Mini 4 Aristo iPhone 4, iPhone 4s 3 GARMIN Tier Aristo 2 PLUS iPhone 5, iPhone 5c, iPhone 5s dLite iPhone 6s Garminfone 3 GS170 iPhone SE 1 Watch Series 3 K7, K10 GEOTAB Tier K20 Plus Leon iPad Air SyncUP FLEET 1 Optimus L90 iPad Mini 3 Sentio iPad Pro 9.7 Google Tier iPhone 6 4 DoublePlay iPhone 6s Plus Pixel 3a G Pad F 8.0 iPhone 7, iPhone 7 Plus Pixel 3a XL 3 Watch Series 4 G Pad X2 8.0, G Pad X2 8.0 Plus G Pad X 8.0 Pixel 3 4 G Stylo iPad Pro 10.5-inch Pixel 3 XL G2 iPad Pro 11-inch G2x iPad Pro 12.9-inch 2 Tier1 K30 iPhone 6 Plus 5 HTC iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus Lion Desire iPhone X myTouch iPhone XR Optimus F3, F3Q, F6, L9, T iPhone XS, iPhone XS MAX Amaze 4G Stylo 2 PLUS, Stylo 3 PLUS Dash 3G Stylo 4 G2 V20 ASUS Tier HD2, HD7 life G3, G5, G6 Google Nexus 7 2 myTouch 3G 1.2, myTouch 3G slide 2 G-Slate myTouch 4G Nexus 4, Nexus 5 3 One M9 P Plus BlackBerry Tier One S Q7+ Radar 4G 7100T, 7105T Shadow G Flex 7230, 7290 G7 Wildfire S 4 8120, 8520 G8 9780 Bold 2 10 V30 Classic Flyer Curve V10 myTouch 5 myTouch 4G Slide 3 V30+ 9700 Bold 3 One Sensation 4G Windows Phone 8X Please note: If you switch your device to one that is classified in another tier, the monthly charge for your new tier will be reflected on your T-Mobile bill. -

Supported Android Devices AT&T KDDI Minor Carriers / Other

AT&T Appendix Acer Iconia Tab A501 (A501) A – HTC Aria (LIBERTY) Supported HTC Lele (HTCPH06130) Android HTC Nexus One (NEXUSONE) HTC One VX (HTCPM36100) Devices HTC One X (HTCONEX) HTC Status (HTCSTATUS) HTC Vivid (HTCPH39100) Huawei Impulse 4G (HUAWEIU8800-51) LG Eclipse (LG-E970) LG Escape 4G (LG-P870) LG Nitro HD (LG-P930) LG Phoenix (LG-P505) LG Thrill 3D (LG-P925) LG Thrive (LG-P506) Motorola Atrix 2 (MB865) Motorola Atrix 3 (MB886) Motorola Bravo MB520 (MB520) Motorola FlipSide (MB508) Pantech Crossover (PANTECHP8000) Samsung Captivate (SAMSUNG-SGH-I897) Samsung Captivate Glide (SAMSUNG-SGH-I927) Samsung Galaxy Express (SAMSUNG-SGH-I437) Samsung Galaxy Note (SAMSUNG-SGH-I717) Samsung Galaxy Note II (SGH-I317) Samsung Galaxy Rugby Pro (SAMSUNG-SGH-I547) Samsung Galaxy S II (SAMSUNG-SGH-I777) Samsung Galaxy S III (SAMSUNG-SGH-I747) Samsung Galaxy S4 (SAMSUNG-SGH-I337) Samsung Galaxy Tab 8.9 (SGH-I957) Samsung Galaxy Tab 8.9 (SAMSUNG-SGH-I957) Samsung Rugby (SAMSUNG-SGH-I847) Samsung SkyRocket (SAMSUNG-SGH-I727) Sony Xperia T (LT30AT) KDDI HTC EVO 3D (ISW12HT) Minor Carriers / Other* LG Nexus 4 (NEXUS4) LG Optimus One (LG-P500) Motorola RAZR i (XT890) Samsung Galaxy Ace (GT-S5830) Samsung Galaxy SII LTE (SGH-I727R) Samsung Galaxy S III (GT-I9300) * Other denotes a device that is not officially carried by a network and is usually purchased unlocked. 1 Version 15 Sprint HTC EVO 3D (PG86100) HTC EVO 4G (PC36100) HTC EVO 4G LTE (EVO) HTC EVO Shift 4G (PG06100) HTC EVO View 4G (PG41200) HTC Hero (HERO200) HTC One (HTCONE) Kyocera ECHO -

Press Release

Global Web Site www.lg.com LG OPTIMUS One (LG-P500) Specifications & Features Type Full Touch Bar Type HSDPA 7.2 RF band WCDMA : 900 / 2100 GSM: 850 / 900 / 1800 / 1900 Dimension: L*W*D (mm) 113.5 x 59 x 13.3 mm CPU 600 MHz Weight with Batt. Standard (g) 129 g Standard Battery 1500 mAh Basic Specification Standby time, Max (hr) 700 hr (2G) / 550 hr (3G) Talk Time (hr) 480 min (2G) / 450 min (3G) External LCD (Pixel): 3.2" HVGA (320 x 480) Display Capacitive Touchscreen Number of Color 256K Vibration Alert ● SIM Toolkit ● GPRS / EDGE (Class) ●(10) / ●(10) OS Android 2.2 (Froyo) ● SMS / EMS / MMS ● / ● / ● Video MMS ● Messaging E Mail ● (IMAP4 / SMTP / POP3) Predictive Text Input (T9) ● Instant Messaging ● (Google Talk) HTML (version) ● (4.01) Wi-Fi ● (802.11 b/g) Internet Google Mobile Service ● Download / Save as Support ● Data Connectivity USB / PC Sync ● (2.0 Hi-Speed) / ● Scheduler / Alarm ● / ● PIM Phonebook (Number of Contacts) ● (Practically Unlimited) Wallpaper / Screensaver ● / - Personalization Picture / Ring Tone Downloading ● / ● G Sensor ● Proximity Sensor ● Advanced Features Digital Compass ● MIDI (poly) ● (72) Key Tone Effect ● Global Web Site www.lg.com LG OPTIMUS One (LG-P500) Specifications & Features Built-in Game (Number of Games) Varies by Country / JAVA Game (Data CD) FM Radio ● Speaker Phone ● Audio Codec ● (WMA, (e) AAC+ / WAV) Video Codec ● (H.263, H264, MP4, WMV, AVI, DivX / Xvid,) Video Encoding ● (H/264 / MPEG4: VGA 18fps) Image / Video Capture ● / ● Camera ● (3.0MP, AF) Internal Memory 170MB (User memory) External Memory ● (Micro SD: Up to 32GB support) MP3 ● Voice Recording ● A-GPS ● Blue-Tooth (version) ● (2.1+EDR) Document Viewer ● (PDF, DOC, PPT, XLS, GIF, JPG, TXT) Battery ● (Included) EarPhone ● (Included) Packaging ● (Included) Manual ● (Included) CD Varies by Country Accessory USB Cable ● (Included) Memory Card ● (2GB Micro SD card included) Memory Socket ● TA ● (Included) Cradle ● (Optional) B/T Headset ● (Optional) Carkit ● (Optional) .