Christine and the Queens: Using Performance to Subvert Binary Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P35-40 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2017 lifestyle MUSIC & MOVIES Riding high, BeyoncE fails to break Grammy curse s Beyonce too edgy for the music industry? Or do the debut album was edged out by in 2013 by English folk "'Lemonade' is really about how black women are treated Grammy Awards suffer from an underlying racial bias? revivalists Mumford & Sons, chose not to even submit his fol- in society historically, and in the contemporary moment, IThe superstar's failure to win top prizes is vexing her low-up, "Blonde," for Grammy consideration. After Sunday's and it's about loving ourselves through all of that," said many admirers-among them the night's big winner Adele. awards, Ocean wrote an open letter asking the Grammy LaKisha Simmons, an assistant professor of history and Beyonce had led the Grammy nominations with nine for organizers to discuss the "cultural bias and general nerve women's studies at the University of Michigan. "So in some "Lemonade," her most daring album to date, which she damage" caused by the show. ways, it's kind of fitting that she was left standing there," she crafted as a celebration of the resilience of African Ocean, who defiantly released "Blonde" independently, said. "Beyonce will be fine," she said. "But I think for the rest American women. But Beyonce, whose tour was one of the said he initially wanted to take part in the Grammys for the of us, it stings because of that-it's almost like, 'Get back in industry's most lucrative in 2016, took only two awards tribute to late pop icon Prince. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

Ukmva-18-Shortlist-Booklet-Email.Pdf

uk music video awards 18 ten years on from the very first uk music video awards, it’s been exciting to see entries coming in from all around the globe in greater numbers than ever, from regular ukmva participants, former nominees and first-time entrants. this year more than 1800 videos were submitted for judging. 400 jury members were invited to vote in round 1 and the top-voted entries were reviewed by 100 industry professionals in a series of live judging panels. the entries for the individual awards for director, new director, producer, commissioner, artist and production company, based on a body of work from the past year, were voted on by jury members. it is thanks to the participation of the jury members that the uk music video awards is a respected and valued competition. our special thanks go to our friends at the mill, bfi stephen street, and black dog films for hosting judging sessions, and to martin roker, carrie sutton, toby abbott, dan massie, barnaby laws, dan kreeger and thom trigger who chaired panels. the uk music video awards 2018 will take place at london’s legendary roundhouse on thursday 25 october. we will be presenting more than 30 awards for achievement in music video and music film, and we will be proud once again to bring together british and international music filmmaking talent for one night under one roof to celebrate the most creative, innovative and successful work of the past 12 months. we look forward to seeing you there. the ukmva team ukmva.com special thanks to the mill london for hosting the 2018 ukmva -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 2pac Me Against The World 12" - 2020 Reissue 24.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your Service 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm 12" Reissue 26.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 15.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 American Aquarium Lamentations 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Bird My Finest Work 12" 22.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Angelo Badalamenti Twin Peaks - Ost 12" - Ltd Green 20.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

File Type Pdf Music Program Guide.Pdf

MOOD:MEDIA 2020 MUSIC PROGRAM GUIDE 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hitline* ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Current Top Charting Hits Sample Artists: Bebe Rexha, Shawn Mendes, Maroon 5, Niall Sample Artists: Ariana Grande, Zedd, Bebe Rexha, Panic! Horan, Alice Merton, Portugal. The Man, Andy Grammer, Ellie At The Disco, Charlie Puth, Dua Lipa, Hailee Steinfeld, Lauv, Goulding, Michael Buble, Nick Jonas Shawn Mendes, Taylor Swift Hot FM ‡ Be-Tween Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Family-Friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Ed Sheeran, Alessia Cara, Maroon 5, Vance Sample Artists: 5 Seconds of Summer, Sabrina Carpenter, Joy, Imagine Dragons, Colbie Caillat, Andy Grammer, Shawn Alessia Cara, NOTD, Taylor Swift, The Vamps, Troye Sivan, R5, Mendes, Jess Glynne, Jason Mraz Shawn Mendes, Carly Rae Jepsen Metro ‡ Cashmere ‡ Chic Metropolitan Blend Warm Cosmopolitan Vocals Sample Artists: Little Dragon, Rhye, Disclosure, Jungle, Sample Artists: Emily King, Chaka Khan, Durand Jones & The Maggie Rogers, Roosevelt, Christine and The Queens, Flight Indications, Sam Smith, Maggie Rogers, The Teskey Brothers, Facilities, Maribou State, Poolside Diplomats of Solid Sound, Norah Jones, Jason Mraz, Cat Power Pop Style Youthful Pop Hits Divas Sample Artists: Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift, DNCE, Troye Sivan, Dynamic Female Vocals Ellie Goulding, Ariana Grande, Charlie Puth, Kygo, The Vamps, Sample Artists: Chaka Khan, Amy Winehouse, Aretha Franklin, Sabrina Carpenter Ariana Grande, Betty Wright, Madonna, Mary J. Blige, ZZ Ward, Diana Ross, Lizzo, Janelle Monae -

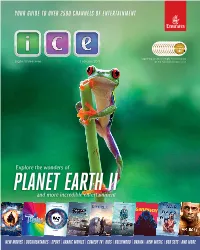

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 the Language Learner

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 TITLE The Language Learner: Reaching His Heartand Mind. Proceedings sr the Second International Conference. INSTITUTION New York State Association ofForeign Language Teachers.; Ontario Modern LanguageTeachers' AssociatIon. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 298p.; Conference held in Toronto,Ontario, March 25-27, 1971 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS Articulation (Program); AudiolingualMethods; Basic Skills; Career Planning; *Conference Reports;English (Second Language); *Instructional ProgramDivisions; Language Laboratories; Latin; *LearningMotivation; Low Ability Students; *ModernLanguages; Relevance (Education); *Second Language Learning;Student Interests; Student Motivation; TeacherEducation; Textbook Preparation ABSTRACT More than 20 groups of commentaries andarticles which focus on the needs and interestsof the second-language learner are presented in this work. Thewide scope of the study ranges from curriculum planning to theoretical aspects ofsecond-language acquisition. Topics covered include: (1) textbook writing, (2) teacher education,(3) career longevity, (4) programarticulation, (5) trends in testing speaking skills, (6) writing and composition, (7) language laboratories,(8) French-Canadian civilization materials,(9) television and the classics, (10)Spanish and student attitudes, (11) relevance and Italianstudies, (12) German and the Nuffield materials, (13) Russian and "Dr.Zhivago," (14) teaching English as a second language, (15)extra-curricular activities, and (16) instructional materials for theless-able student. (RL) a a CONTENTS KEYNOTE ADDRESS: DR. WILGA RIVERS 1 - 11 HOW CAN STUDENTS BE INVOLVED IN PLANNING THE LANGUAGE CURRICULUM 12 - 24 TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF A LANGUAGE TEXTBOOK WRITER 25 - 38 PREPARING FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHERS: NEW EMPHASIS IN THE 70'S 39 - 52 STAMINA AND THE LANGUAGE TEACHER: WAYS IN WHICH TO ACHIEVE LONGEVITY 53 - 64 A SEQUENTIAL LANGUAGE CURRICULUM IN HIGHER EDUCATION 65 - 81 NEW TRENDS IN TESTING THE SPEAKING SKILL IN ELEM AND SEC. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon