Jake Shields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How I Got the Job at Adidas Combat Gear When I Initially Heard About Adidas Combat Sports USA, It Was Through My Friend Jeff

How I Got The Job at Adidas Combat Gear When I initially heard about adidas Combat Sports USA, it was through my friend Jeff Chu, a local photographer and videographer. He had taken on a job as part of his freelance career and since I had recently been laid off from a magazine I was working for, decided to tag along. "It's all about the networking in this business," Jeff said. And it is. Because I tagged along, I met ACS President Scott Viscomi and five months later had a job as a blog editor of this website. Before Scott had taken on the task of creating some of the best gear in the combat sports industry, the adidas logo had entered the realm of jiu-jitsu competition when I was only a white belt years ago. Or at least that's the first time I had seen it. The gis that were created then were more cut for a judo competitor, with short sleeves and stiff material. It wasn't pliable, equipt to move along with a jiu-jitsu athlete while playing spider guard or butterfly guard, or passing guard and taking the back. Somewhere along the line, before I ever saw an adidas gi again, the design changed. It was in new hands. As I walked into Church Street Boxing in Lower Manhattan, it was a lot different from the jiu-jitsu academies I'd trained in for six years. In the middle of the main room was a raised boxing ring and all around it were walls covered in mirrors and old photographs and fight posters. -

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

State of Nevada

STATE OF NEVADA MIXED MARTIAL ARTS SHOW RESULTS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY DATE: November 11, 2006 LOCATION: Hard Rock Hotel, Las Vegas ATHLETIC COMMISSION Referee: Steve Mazzagatti Telephone (702) 486-2575 Fax (702) 486-2577 Visiting Referees: Herb Dean, Yves, Lavigne, John McCarthy COMMISSION MEMBERS: Judges: Adalaide Byrd, Glenn Trowbridge, Tony Weeks Chairman: Dr. Tony Alamo Visiting Judges: Lester Griffin, Dave Hagen, Gene LeBell, Marcos Rosales Skip Avansino, Jr. John R. Bailey Timekeepers: Jane Broadfoot, Ernie Jauregui Joe W. Brown Ringside Doctors: James Game, Jeff Davidson, Anthony Ruggeroli, David Watson T. J. Day Ring Announcer: Bruce Buffer Promoter: Zuffa, LLC EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Keith Kizer Matchmaker: Dana White Contestants Results Rds Date of Birth Weight Remarks CHRIS SCOTT LYTLE Serra won by split decision. 3 08/18/74 170 Suspend Lytle until 12/12/06 New Palestine, IN Lytle – Serra No contact until 12/03/06 ----- vs ----- 27-30; 27-30; 30-27 MATTHEW JOHN SERRA Griffin, Rosales, Trowbridge East Meadow, NY **Serra wins The Ultimate Fighter ™ 06/02/74 170 Season 4 Welterweight Finale Referee: Herb Dean PATRICK COTE Lutter won by tap out 2:18 of the 1st 3 02/29/80 185 Beauport. Quebec, Canada round – arm bar. ----- vs ----- TRAVIS S. LUTTER **Lutter wins The Ultimate Fighter ™ 05/12/73 186 Referee: John McCarthy Fort Worth, TX Season 4 Middleweight Finale RICHARD THOMAS CLEMENTI Thomas won by tap out 3:11 of the 2nd 3 03/31/76 156 Suspend Clementi until 12/12/06 Slidell, LA round – rear naked choke. No contact until 12/03/06 ----- vs ----- DIN YERO THOMAS Suspend Thomas until 12/12/06 09/28/76 155 No contact until 12/03/06 – facial laceration Port St. -

Rules Shooto

Rules Shooto tournaments are held under a strict and comprehensive set of rules. Its objectives are to protect the athlete and to ensure dynamic and fair fights. A distinction is made between amateur (Class C), semi-pro (Class B) and professional (Class A) rules. Depending on the class, certain techniques are prohibited and the fight duration is adapted as well. The different classes in Shooto make it possible for athletes to improve in a controlled and safe environment. Weight classes Featherweight – 60kg Lightweight – 65kg Welterweight – 70kg Middleweight – 76kg Light-Heavyweight – 83kg Cruiserweight – 91kg Heavyweight – +91kg Rules – Brief Version — A pro fight consists of three 5-minute rounds with one-minute breaks in between. Amateurs fight two 3-minute rounds, semi-pros fight two 5-minute rounds. — A referee oversees the fight in the ring and controls adherence of the rules. — Three judges score the fight according to effective strikes, takedowns and aggressivity/activity whilst standing and dominant positions, submission attempts and defense whilst being on the floor. — A victory can be scored by judges decision, knock-out (KO), technical knock-out (TKO), by submission or by referee- or doctor-stoppage. — Fighters are divided by weight classes. — Before the fight, fighters have to attend a medical check and the doctor needs to approve the fight. — Protective equipment (gloves, cup, mouthguard) are mandatory. Amateurs (C-class) are allowed to fight with headgear and shinguards. — Illegal fouls are headbutts, elbow-strikes, biting, groin attacks of any kind, attacks on the back or the back of the head, attacks on small joints, attacks on the eyes or ears and further actions which oppose a fair fight. -

BISPING: Barnett Needs to Push the Pace Vs. Nelson

FS1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 9/23/15 BISPING: Barnett Needs To Push The Pace Vs. Nelson Florian: “Uriah Hall Is Too Dangerous To Just Stand and Trade With” LOS ANGELES – UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian and guest host Michael Bisping break down the upcoming FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BARNETT VS. NELSON. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT guest host Michael Bisping on how Josh Barnett can beat Roy Nelson: “Josh needs to not get hit by the right hand of Roy. He needs to push the pace of the fight, move forward, and push Roy up against fence and brutalize him with knees and elbows like he did with Frank Mir. Most of his finishes came from the clinch position. He finishes fights against the fence. He did that against Frank Mir.” UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian on Barnett avoiding Nelson’s knock out power: “Josh doesn’t want to be on the outside where Roy’s right hand can get him. He wants to be on the inside. He’s been busy on the submission circuit. He’s dangerous on the mat and that’s where he wants to get Roy.” Bisping on how Nelson should fight Barnett: “What Roy can’t get is predictable. If he just tries to throw the big right hand, Barnett is going to see it coming. Roy has to mix up his striking. I’m not sure he’s going to go for takedowns. But he has to mix his striking. His right hand and left hooks, to keep Josh at bay.” Florian on Nelson mixing up his strikes: “The knock on Nelson is his lack of evolution. -

Vazquez and Hallman V. Zuffa Complaint

Case5:14-cv-05591-PSG Document1 Filed12/22/14 Page1 of 62 1 Joseph R. Saveri (State Bar No. 130064) Joshua P. Davis (State Bar No. 193254) 2 Andrew M. Purdy (State Bar No. 261912) Kevin E. Rayhill (State Bar No. 267496) 3 JOSEPH SAVERI LAW FIRM, INC. 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 625 4 San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: (415) 500-6800 5 Facsimile: (415) 395-9940 [email protected] 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 [email protected] 8 Benjamin D. Brown (State Bar No. 202545) Hiba Hafiz (pro hac vice pending) 9 COHEN MILSTEIN SELLERS & TOLL, PLLC 1100 New York Ave., N.W., Suite 500, East Tower 10 Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 408-4600 11 Facsimile: (202) 408 4699 [email protected] 12 [email protected] 13 Eric L. Cramer (pro hac vice pending) Michael Dell’Angelo (pro hac vice pending) 14 BERGER & MONTAGUE, P.C. 1622 Locust Street 15 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Telephone: (215) 875-3000 16 Facsimile: (215) 875-4604 [email protected] 17 [email protected] 18 Attorneys for Individual and Representative Plaintiffs Luis Javier Vazquez and Dennis Lloyd Hallman 19 [Additional Counsel Listed on Signature Page] 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 21 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION 22 Luis Javier Vazquez and Dennis Lloyd Hallman, Case No. 23 on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, 24 ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT 25 v. 26 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Zuffa, LLC, d/b/a Ultimate Fighting 27 Championship and UFC, 28 Defendant. 30 Case No. 31 ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 32 Case5:14-cv-05591-PSG Document1 Filed12/22/14 Page2 of 62 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 3 I. -

Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Villanova University School of Law: Digital Repository Volume 20 Issue 2 Article 4 2013 Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts Daniel Berger Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Berger, Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ultimate Fighting Championship and its Struggle Against the State of New York Over the Message of Mixed Martial Arts, 20 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 381 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol20/iss2/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\20-2\VLS204.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUN-13 13:05 Berger: Constitutional Combat: Is Fighting a Form of Free Speech? The Ul Articles CONSTITUTIONAL COMBAT: IS FIGHTING A FORM OF FREE SPEECH? THE ULTIMATE FIGHTING CHAMPIONSHIP AND ITS STRUGGLE AGAINST THE STATE OF NEW YORK OVER THE MESSAGE OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS DANIEL BERGER* I. INTRODUCTION The promotion-company -

41St National Collegiate Taekwondo Championships Results University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, Colorado April 23-24, 2016

41st National Collegiate Taekwondo Championships results University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, Colorado April 23-24, 2016 Black belt sparring Fin Men 1st Joseph Ong San Jose State University 2nd Matthew Galea United States Military Academy 3rd Adrian Zambrano California State University, Northridge 3rd Michael Ashtari University of California, Davis Female 1st Samery Moras University of Utah 2nd Jacqueline Chong Foothill College 3rd Kyra Duong University of California, San Diego 3rd Janar Bauirjan University of California, Los Angeles Fly Men 1st Tyler Miyagishima California State University, Northridge 2nd Joseph Aguon Tarrant County College 3rd Andrew Cao University of California, Davis 3rd Christopher Yen Brown University Female 1st Taylor Macleod Northern Virginia Community College 2nd Amanda Bodgen University of California, Davis 3rd Jean Chow Massachusetts Institute of Technology 3rd Julia Richieri Tufts University Bantam Men 1st Fouad El-Chemali Sierra College 2nd Drew Pluemer Yale University 3rd Yuuki Jo University of Buffalo 3rd Dough Zhang University of California, Berkeley Female 1st Amanda Flannery University of California, Davis 2nd Mary Essa University of Colorado, Boulder 3rd Alyssa Roseman University of Colorado, Boulder 3rd Diane Kim University of California, Davis Feather Men 1st David Gibson University of California, Davis 2nd Lucas Peltier College of Southern Nevada 3rd Ashtin Gulyard Northern Hennepin Community College 3rd Adan Rivas University of Texas, Austin Female 1st Carly Berger University of California, Davis -

Ufc Welterweight Champion Woodley and Retired Contender Florian Serve As Desk Analysts with Host Bryant for Fs1 Ufc Fight Night: Maia Vs

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: John Stouffer Wednesday, May 16, 2018 [email protected] UFC WELTERWEIGHT CHAMPION WOODLEY AND RETIRED CONTENDER FLORIAN SERVE AS DESK ANALYSTS WITH HOST BRYANT FOR FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: MAIA VS. USMAN No. 1 Flyweight Contender Shevchenko Makes Analyst Debut with Former UFC Heavyweight Champion Werdum and Santiago on FOX Deportes LOS ANGELES – Today, FOX Sports announces UFC welterweight champion Tyron Woodley and retired contender Kenny Florian to serve as desk analysts alongside lead UFC host Karyn Bryant for FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: MAIA VS. USMAN programming on Friday, May 18 and Saturday, May 19. Blow-by-blow announcer Brendan Fitzgerald and veteran MMA analyst Jimmy Smith call the bouts live Octagon-side from Santiago, Chile. Laura Sanko adds reports and interviews fighters on-site. In addition, No. 1-ranked flyweight contender Valentina Shevchenko makes her analyst debut alongside former UFC heavyweight champion Fabricio Werdum and Troy Santiago calling the fights in Spanish on FOX Deportes. Two elite welterweights headline UFC’s first visit to Chile as Kamaru Usman (11-1) faces former title challenger Demian Maia (25-8) in a five-round main event in Santiago. Winner of 11 bouts in a row, including seven in the Octagon over the likes of Leon Edwards and Sergio Moraes, the No. 7-ranked Usman has been a nightmare matchup for everyone he’s faced. He expects similar results against the Brazilian grappling wizard Maia, the No. 5 contender at 170 pounds, who owns wins against top contenders Jorge Masvidal, Carlos Condit, Matt Brown, Neil Magny and Gunnar Nelson. -

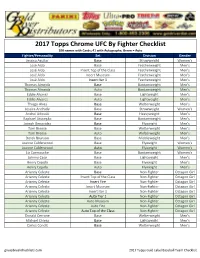

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Npc Bodybuilding Division Rules

NATIONAL PHYSIQUE COMMITTEE OF THE USA PO Box 3711, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15230 USA TOLL FREE: 1-866-304-4322 PHONE: 412-276-5027 FAX: 412-281-0471 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.NPCnewsOnline.com NPC BODYBUILDING DIVISION RULES Posing Music • Posing Music will be used at the Finals only. • Posing Music must be on CD and must be the only music on the CD. • Posing Music should be cued to the start of the music. N • Posing Music must not contain vulgar lyrics. Competitors Membership using music containing vulgar lyrics will be disqualifi ed. Each competitor must be a member of the NPC. Onstage Complete Registration Card • During the Prejudging male and female competitors are not on the back of this Issue. permitted to wear any jewelry onstage other than a wedding band. Decorative pieces in the hair are not permitted. • During the Finals female competitors are permitted to wear earrings. Competitor Rules • No glasses, props or gum are permitted onstage. • Any competitor doing the “Moon Pose” will be disqualifi ed. Check-Ins • Lying on the fl oor is prohibited. Competitors will be checked in and weighed. • Bumping and shoving is prohibited. First and second persons involved will be disqualifi ed. Posing Suits • Competitors numbers will be worn on the left side of the suit • All suit bottoms must be V-shaped, no thongs are permitted. bottom during both Prejudging and Finals. • Suits worn by male competitors at the prejudging and fi nals must be plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle Backstage or fl uorescents. The only people permitted in the backstage area are: • Suits worn by female competitors at the Prejudging must be • Competitors two-piece and plain in color with no fringe, wording, sparkle • Expediters or fl uorescents. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University.