Block 3 Transition to Early Medieval India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somnath Travel Guide - Page 1

Somnath Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/somnath page 1 devotion at the Somnath Temple. It finds Max: Min: Rain: 31.79999923 19.79999923 2.20000004768371 mention in the Hindu puranas and the 7060547°C 7060547°C 6mm Somnath Mahabharata. Literally translated as the Apr Home to one of the 12 sacred Shiva "Lord of the Moon," the town and its temple Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. celebrate the most auspicious Karthik Jyotirlinga's in India, the grandeur Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm Poornima (or full-moon) in the month of 32.09999847 22.79999923 of Somnath is sure to take your 4121094°C 7060547°C November/ December with full fervour and May breath away. The lofty shikharas flavour. The reverberating sounds of Shiv Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. add colour to the town and flavour bhajans and the legend, culture and Max: Min: Rain: to the lives of people who visit it. tradition surrounding it, will accompany you 32.79999923 26.20000076 4.40000009536743 during your entire stay at Somanth. It has 706055°C 2939453°C 2mm been popularly dubbed as the "shrine Jun eternal," for its ability to stand tall in the Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. face of destruction - it's been rebuilt six Famous For : City Max: 32.5°C Min: Rain: times. 27.39999961 134.800003051757 8530273°C 8mm Somnath is famous for its grand Shiva When To Jul temple, one of the 12 revered Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Jyotirlingas, located right on the shore of the umbrella. Arabian Sea, in Max: Min: Rain: VISIT 30.70000076 26.60000038 269.799987792968 Junagadh District. -

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 L85195TG1984PLC004507 Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) CIN/BCIN Prefill Company/Bank Name DR.REDDY'S LABORATORIES LTD 27-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 5729595.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) NEETA NARENDRA SHAH NA NA NA CHANDRIKA APT.,SHINGADA TALAV,W.NO.4016,,NASIKINDIA MAHARASHTRA NASIK DPID-CLID-1201750200019180Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend150.00 30-AUG-2020 ARUN KUMAR RADHAKRISHAN A-40,(60.MEATER),POCKET-00,,SECTOR-2,ROHINI,DELHIINDIA Delhi Delhi FOLIOA00001 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend180.00 30-AUG-2020 AVINASH BALWANT DEV BALWANT 1 JASMIN APARTMENTS,NEW PANDITINDIA COLONY GANGAPURMAHARASHTRA ROAD,NASIK,NASIK NASIK FOLIOA00403 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend60.00 30-AUG-2020 A RAVI KUMAR A KAMESWAR RAO DR. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

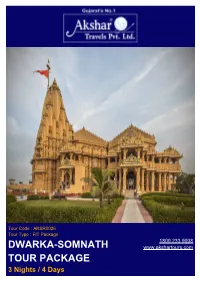

Dwarka-Somnath Tour Package

Tour Code : AKSR0026 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 DWARKA-SOMNATH www.akshartours.com TOUR PACKAGE 3 Nights / 4 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 4Cities 4Days 1Activities Accomodation Meal 02 NIGHTS ACCOMODATION IN DWARKA 03 BREAKFAST 03 DINNER 01 NIGHT ACCOMODATION IN SOMNATH Visa & Taxes Highlights Accommodation on double sharing 5% Gst Extra Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Jamnagar : Lakhota lake , Lakhota museum and Bala hanuman temple. - Dwarka : Bet Dwarka , Nageshwar Jyotirlinga , Rukmani Temple. - Porbandar : Kirti mandir (Gandhiji birth place), Sudama Temple. - Somnath : Somnath jyotirlinga, Triveni sangam, Bhalka tirth. SIGHTSEEINGS JAMNAGAR On an island in the center of the lake stands the circular Lakhota tower, built for drought relief on orders from Jam Ranmalji after the failed monsoons in 1834, 1839 and 1846 made it difficult for the people of the city to find food and resources. Originally designed as a fort such that soldiers posted around it could fend off an invading enemy army with the lake acting as a moat, the tower known as Lakhota Palace now houses the Lakhota Museum. The collection includes artifacts spanning from 9th to 18th century, pottery from medieval villages nearby and the skeleton of a whale. The very first thing you see on entry, however, before the historical and archaeological information, is the guardroom with muskets, swords and powder flasks, reminding you of the structure’s original purpose and proving the martial readiness of the state at the time. The walls of the museum are also covered in frescoes depicting various battles fought by the Jadeja Rajputs. -

(1994) 6 Supreme Court Cases 360 (Before M.N. Venkatachaliah, C.J. and A.M. Ahmadi, J.S. Verma, G.N. Ray, and S.P. Bharucha

(1994) 6 Supreme Court Cases 360 (Before M.N. Venkatachaliah, C.J. And A.M. Ahmadi, J.S. Verma, G.N. Ray, and S.P. Bharucha, JJ.) Transferred Case (C) Nos. 41, 43 and 45 of 1993 Dr. M. Ismail Faruqui and Ors. ..... Petitioners Vs. Union of India and Ors. ..... Respondents With Writ Petition (Civil) No. 208 of 1993 Mohd. Aslam ....... Petitioner Vs. Union of India and others ....., Respondents With Special Reference No. 1 of 1993 with I.A. No. 1 of 1994 in T.C.No. 44 of 1993 Hargyan Singh ..... Petitioner Vs. State of U.P. And Ors. ..... Respondents With Transferred Case (C) No.42 of 1993 Thakur Vijay Ragho Bhagwan Birajman Mandir and Another .... Petitioners Vs. Union of India and Others .... Respondents 1 J. S. VERMA, J. (for Venkatachaliah, C.J., himself and Ray, J)- "We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another." - Jonathan Swift Swami Vivekananda said - "Religion is not in doctrines, in dogmas, nor in intellectual argumentation; it is being and becoming, it is realisation." This thought comes to mind as we contemplate the roots of this controversy. Genesis of this dispute is traceable to erosion of some fundamental values of the plural commitments of our polity. 2. The constitutional validity of the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act, 1993 (No. 33 of 1993) (hereinafter referred to as "Act No. 33 of 1993" or "the Act") and the maintainability of Special Reference No. 1 of 1993 (hereinafter referred to as "the Special Reference") made by the President of India under Art. -

Block 3A Presscopy I

UNIT 11 ORGANISATION OF AGRICULTURAL AND CRAFT PRODUCTION: NORTH INDIA, C. AD 550 – C. AD 1300 Structure 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Extent and Expansion of Agriculture 11.3 Irrigation 11.4 Crops 11.5 Craft Production 11.6 Organisation of Craft Production 11.7 Summary 11.8 Exercises 11.9 Suggested Readings 11.1 INTRODUCTION Studies in the agrarian history of early medieval north India have been dominated by various themes of agrarian relations; aspects of agricultural production, with which we are concerned in this Unit, have received relatively less attention. From early works such as U.N. Ghoshal’s pioneering Contributions to the History of Hindu Revenue System to R.S. Sharma’s Indian Feudalism and later, the focus of our thought has been the history of agrarian relations, relating to the ways in which agrarian surplus was extracted from the producers (e.g. as taxes) and distributed, as also to the various forms in which control over land and producers was claimed and/or exercised (e.g. landownership). No comparable interest has been shown in matters of agricultural production such as land and its productivity, crops, technologies of production, etc. Some important essays have no doubt been written, but there has been no full-fledged attempt at writing a history of agricultural production, as there has been of revenue system or feudal agrarian relations; there are indeed book-length discussions even of the debate whether these relations were feudal or not. The routine compilations of data on agricultural production that are commonly seen in the economic histories of the period lack in historical analysis. -

OIOP Nov 2018

Vol 22/04 Nov 2018 Patriotism Redefined Indian Archaeology, 2018 know india better The stunning ruins of Hampi The fascinating world of archaeology The startling story of Ajanta FACE TO FACE Excavating of Nagardhan Dr. Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Great Indians : Kavi Gopaldas ‘Neeraj’ | Annapurna Devi | Captain Sunil Kumar Chaudhary, KC, SM MORPARIA’S PAGE Contents November 2018 VOL. 22/04 THEME: Morparia’s Page 02 INDIAN The fascinating world of archaeology 04 ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 Dr. Kaushik Gangopadhyay Managing Editor The startling story of Ajanta 07 Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde Shubha Khandekar Excavating of Nagardhan 09 Abhiruchi Oke Editor The mute witnesses 11 Anuradha Dhareshwar Harshada Wirkud The footprints of the caveman 14 Satish Lalit Assistant Editor The Deccan discovery 16 E.Vijayalakshmi Rajan Varada Khaladkar Jaina basadis of North Karnataka 30 Abdul Aziz Rajput Design Resurgam Digital LLP Know India Better The stunning ruins of Hampi 17 Usha Hariprasad Subscription In-Charge Nagesh Bangera Face to Face Dr. Arvind P. Jamkhedkar 25 Raamesh Gowri Raghavan Advisory Board Sucharita Hegde General Justice S. Radhakrishnan Venkat R. Chary Killing a Tigress 32 Harshad Sambhamurthy Paper cups, not a choice 34 Usha Hariprasad Printed & Published by Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde for One India One People Foundation, Mahalaxmi Chambers, 4th floor, Great Indians 36 22, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai - 400 026 Tel: 022-2353 4400 Fax: 022-2351 7544 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] visit us at: KAVI GOPALDAS “NEERAJ” ANNAPURNA DEVI CAPTAIN SUNIL KUMAR www.oneindiaonepeople.com CHAUDHARY, KC, SM www.facebook.com/oneindiaonepeoplefoundation INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 The fascinating world of archaeology The field of archaeology in India still exhibits a colonial hangover. -

Abstracts of Medico-Historical Articles in Hindi Journals

ABSTRACTS OF MEDICO-HISTORICAL ARTICLES IN HINDI JOURNALS P. D. JOPAT* 1. Vaidik-sahitya Me Kankal Tantra (Skeleton-System in Vedic Literature) by Suresh Chandra Srivastava, Ayurvedavikas February - March 1979; 18,2& 3; pp. 19-30 & 12 - 19. This article in two parts deals with the anatomical information availa- ble in Vedic literature. The systematic description of various tissues, musc- les and bones of the body is found in a chapter of the Atharvaveda,which pertains to the treatment of Kilasa, Similar description about hair, skin, muscles and bones is available in Aitareya Br ahmana. In Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, an analogy bas been drawn between the human body and a tree wberein the bair, skin, blood, muscles, nerves and bones of human beings have been held analogous to tbe leaves, bark, fluid or latex, cortex. pericycJe and wood of the plants. The number of bones as mentioned ill Charakasa- mbita & Sushrutasamhit a has been compared with that given in Vedic literature. An elaborate chart comparing the part wise bones in the three different works together witb the modern counter parts is given. The diff- erent technical terminologies occurring in Vedic literature with anatomical significance have been defined in the proper perspective. The different parts and their component individual bones which are discussed at length in this paper are cervical vertebrae, mandible, frontal, parietal occipital, temporal, nasal, molar, auditory ossicles, spbeniodal sacrum, coccyx, thoracic, lumbar ribs, sternum, clavicle, phalanges, metatarsals, tarsus, tibia, t rbula, femur etc. 2. Kakachandishwar KaJpa Tantrokta Aushadhiyan (Medicines described in Kakachandishvara Kalpa Tantra) by V.P.Tiwari. D.N.Tiwari 0.: Praja- pati Joshi, Ayurvedavikas, April-May, 1979, 18,4 & 5, pp.9-15 and 9-19. -

Design and Synthesis of Novel Fluorescence Constructs for The

DESIGN AND SYNTHESIS OF NOVEL FLUORESCENCE CONSTRUCTS FOR THE DETECTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL ARSENIC by VIVIAN CHIBUZO EZEH (Under the Direction of TODD C. HARROP) ABSTRACT Arsenic compounds are classified as group 1 carcinogens and the maximum contamination level in drinking water is set at 10 ppb by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Methods currently approved for monitoring environmental arsenic are classified as colorimetric and instrumental methods. However, toxic byproducts (arsine gas and mercury) are formed in colorimetric methods, while instrumental methods require high maintenance costs. Therefore developing a sensitive, safe, and less expensive detection technique for arsenic is needed. One strategy involves the development of new imaging tools using small molecule fluorescent sensors, which will offer a sensitive and inexpensive method of arsenic detection in environmental samples. Emphasis will be on As(III) compounds because they are prevalent in the environment. To accomplish this goal, the coordination chemistry of As(III) was studied to discover new As(III) chemistry/preference for thiols. One finding from this work is the As(III)-promoted redox rearrangement of a benzothiazoline-containing compound to afford a four-coordinate As(III) complex and the benzothiazole analog. The knowledge gained was used to design two fluorescent chemodosimeters for As(III). The first generation sensors, named ArsenoFluors (AFs), were designed to contain a benzothiazoline functional group appended to a coumarin fluorescent reporter and were prepared in high yield by multi-step organic synthesis. The sensors react with As(III) to afford a highly fluorescent coumarin-6 dye (benzothiazole analog), which results in a 20 – 25 fold increase in fluorescence intensity and 0.14 – 0.23 ppb detection limit for As(III) in THF at 298 K. -

Effect of Phosphorus Addition in Steel: Processed Through Cast Route and Powder Metallurgy Route

Journals of Mechatronics Machine Design and Manufacturing Volume 1 Issue 2 Effect of Phosphorus Addition in Steel: Processed Through Cast Route and Powder Metallurgy Route Shefali Trivedi*1, Parag Gupta2 1Assistant Professor, 2M.Tech Student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, J. C. Bose University of Science and Technology YMCA, Faridabad, Haryana, India Email: *[email protected] DOI: http://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.3556177 Abstract In general alloying elements are added in Iron to enhance its mechanical, electrical, attractive and tribological properties. Phosphorus is a vital alloying component in steel, since it was discovered. The addition of phosphorus content in the low carbon steels results in viably enhancement of the strength. Phosphorus additionally enhances wear resistance, magnetic properties and corrosion resistance of steel. Fe-P steels have been processed through wrought as well as powder metallurgy route. However, production of Fe- P steels through wrought processing route is troublesome due to tendency of phosphorus to isolate along the grain boundaries during solidification. Phosphorus segregation along the grain boundaries in cast route can be avoided by alloy designing. Fe-P steels have been developed through powder metallurgy route. High density Fe-P steels have been developed through powder pre-form technique. This high strength steel is valuable in basic structural applications such as to make rebars for reinforcement, corrugated sheets for roofing, flats, angles, beams, trusses etc. Fe-P steels are less expensive to existing high strength good wear and good corrosive materials. Keywords: Fe-P steels, corrosion resistance, mechanical properties, wear resistance INTRODUCTION ferrite stabilizer, alloying element in steels. The alloying elements used in steels are of It was found that the plain carbon steels two types. -

List of Publications of Prof. R. Balasubramaniam

Publications of Prof. R. Balasubramaniam Journal Publications: 1. On Stress Corrosion Cracking in Aluminium-Lithium Alloys R.Balasubramaniam, D.J. Duquette and K. Rajan Acta Metallurgica et Materialia, 39 (1991) 2597-2605. 2. Hydride Formation in an Al-Li-Cu Alloy R.Balasubramaniam, D.J. Duquette and K. Rajan Acta Metallurgica et Materialia, 39 (1991) 2607-2613. 3. Elastic Moduli of Binary BCC Solid Solutions of Group Vb Elements R.Balasubramaniam Journal of Nuclear Materials, 187 (1992) 180-182. 4. Solution Thermodynamics of Hydrogen in MmNi5 with Aluminium, Manganese and Tin Substitutions R.Balasubramaniam, M.N. Mungole, K.N. Rai and K.P. Singh Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 185 (1992) 259-271. 5. Oxidation Behaviour of Hard and Binder Phase Modified WC-10Co Cemented Carbides S.K. Bhaumik, R. Balasubramaniam, G.S. Upadhyaya and M.L. Vaidya Journal of Materials Science Letters, 11 (1992) 1457-1459. 6. Hydrogen Storage Properties of MmNi5-x Mnx Systems using Indian Mischmetal M.N. Mungole, K.N. Rai, R.Balasubramaniam and K.P. Singh International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 17 (1992) 607-611. 7. Hydrogen Storage Properties of the MmNiO.6SnO.4 System M.N.Mungole, R.Balasubramaniam, K.N.Rai and K.P.Singh International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 17 (1992) 603-606. 8. Elastic Moduli of Ti-V, V-Cr and Ti-Cr Alloys R.Balasubramaniam Physica Status Solidi, 132 (1992) K23-K26. 9. Theoretical Analysis of Stress Corrosion Cracking in Al-Li Alloys K.Narayanaswamy and R.Balasubramaniam Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals, 45 (1992) 253-255. 10. -

10.1: Literature: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit and Tamil 10.2: Scientific and Technical Treatises Author: Dr

Subject: History Lesson: Cultural development Course Developers : 10.1: Literature: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit and Tamil 10.2: Scientific and technical treatises Author: Dr. Shonaleeka Kaul Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi 10.3: Understanding Indian art: changing perspectives Author: Dr. Parul Pandya Dhar Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi 10.4: Art and architecture: patronage 10.5: The Mauryan phase: monumental architecture, stone sculpture and terracottas Author: Dr. Snigdha Singh Associate Professor, Miranda House, University of Delhi 10.6: The early stupa: Sanchi,Bharhut, Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda 10.7: The rock-cut cave: Western Ghats, Udayagiri and Khandagiri 10.8: Sculpture: regional styles (up to c. 300 CE): Gandhara, Mathura and Amaravati Author: Dr. Devika Rangachari Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of History, University of Delhi, and writer 10.9: Rock cut caves: architecture, sculpture, painting 10.10: Temple architecture, c. 300 - 750 CE 10.11: Ancient Indian sculpture, c. 300 - 700 CE Author: Sanjukta Datta Ph.D Scholar, Department of History, University of Delhi Language Editor: Veena Sachdev Production Editor: Ashutosh Kumar Assistant Professor, Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi NOTE: The dates in modern historical writings are generally given according to the Christian calendar. In recent years, the use of AD (Anno Domini) and BC (Before Christ) has to some extent been replaced by BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era). Both usages are acceptable,