Chapter 38 – Seabirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHORT-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna Tenuirostris Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional Migrant Monotypic

SHORT-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna tenuirostris non-breeding visitor, occasional migrant monotypic The Short-tailed Shearwater breeds on islands off S and SE Australia in Nov- May, disperses northward through the W Pacific to the Bering Sea in May-Aug, and migrates rapidly southwestward in large flights across the central Pacific, back the breeding grounds, in Sep-Nov (King 1967, Harrison 1983, AOU 1998, Howell 2012). In the Hawaiian Islands, large numbers have been recorded during well-defined pulses in fall migration, and several sight observations of one to a few birds suggest a smaller passage in spring. The Short-tailed Shearwater is extremely difficult to separate from the similar Sooty Shearwater in the field (see Sooty Shearwater), especially when viewing isolated individuals (King 1970); thus, confirmation of the spring passage with specimen or photographic evidence is desirable. Short-tailed Shearwater was placed in genus Puffinus until moved to Ardenna by the AOU (2016). At sea, Short-tailed Shearwaters were recorded in large numbers during 2002 HICEAS, with 37,874 individuals observed on 52 of 163 observing days from W of Kure to S of Oahu (Rowlett 2002; HICEAS data); they were observed from 1 Sep to 14 Nov. Over 1,000 birds were recorded on each of seven dates, with a large peak of >28,000 recorded 13-22 Sep 2002 between Midway and Lisianski and a smaller peak of >4,000 recorded 30 Oct-14 Nov between Laysan and Kaua'i. All birds were flying SSW in concentrated groups. In contrast to Sooty Shearwater, Short-taileds were clearly more abundant in Northwestern than Southeastern Hawaiian Island waters during fall passage; only 66 birds were recorded on 3 of 35 dates during this period off the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands. -

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 651: 163–181, 2020 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published October 1 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13439 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPEN ACCESS Habitat preferences, foraging behaviour and bycatch risk among breeding sooty shearwaters Ardenna grisea in the Southwest Atlantic Anne-Sophie Bonnet-Lebrun1,2,3,8,*, Paulo Catry1, Tyler J. Clark4,9, Letizia Campioni1, Amanda Kuepfer5,6,7, Megan Tierny6, Elizabeth Kilbride4, Ewan D. Wakefield4 1MARE − Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, ISPA - Instituto Universitário, Rua Jardim do Tabaco 34, 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 3Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive CEFE UMR 5175, CNRS — Université de Montpellier - Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier — EPHE, 34293 Montpellier cedex 5, France 4Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 5FIFD — Falkland Islands Fisheries Department, Falkland Islands Government, PO Box 598, Stanley, Falkland Islands, FIQQ 1ZZ, UK 6SAERI — South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute, Stanley, Falkland Islands, FIQQ 1ZZ, UK 7Environment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK 8Present address: British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB4 0ET, UK 9Present address: Wildlife Biology Program, Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences, W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA ABSTRACT: Pelagic seabirds are important components of many marine ecosystems. The most abundant species are medium/small sized petrels (<1100 g), yet the sub-mesoscale (<10 km) distri- bution, habitat use and foraging behaviour of this group are not well understood. Sooty shearwaters Ardenna grisea are among the world’s most numerous pelagic seabirds. -

Sooty Shearwater Puffinus Griseus Few Changes in Bird Distribution

110 Petrels and Shearwaters — Family Procellariidae Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus birds are picked up regularly on the county’s beaches. Few changes in bird distribution have been as sud- Winter: From December to March the Sooty Shearwater den and dramatic as the Sooty Shearwater’s deser- is rare—currently much scarcer than the Short-tailed tion of the ocean off southern California. Before the Shearwater. Before 1982, winter counts ranged up to 20 1980s, this visitor from the southern hemisphere off San Diego 18 January 1969 (AFN 23:519, 1969). Since was the most abundant seabird on the ocean off San 1987, the highest winter count has been of three between San Diego and Los Coronados Islands 6 January 1995 (G. Diego in summer. After El Niño hit in 1982–83 and McCaskie). the ocean remained at an elevated temperature for the next 20 years, the shearwater’s numbers dropped Conservation: The decline of the Sooty Shearwater by 90% (Veit et al. 1996). A comparison confined followed quickly on the heels of the decline in ocean to the ocean near San Diego County’s coast would productivity off southern California that began in the likely show a decline even steeper. late 1970s: a decrease in zooplankton of 80% from 1951 to 1993 (Roemich and McGowan 1995, McGowan et al. Migration: The Sooty Shearwater begins arriving in April, 1998). The shearwater’s declines were especially steep in peaks in May (Briggs et al. 1987), remains (or remained) years of El Niño, and from 1990 on there was no recov- common through September, and then decreases in ery even when the oceanographic pendulum swung the number through December. -

First Record, and Recovery of Wedge-Tailed Shearwater Ardenna Pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India S

RAJESHKUMAR ET AL.: Wedge-tailed Shearwater 113 First record, and recovery of Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India S. Rajeshkumar, C. Raghunathan & N. P. Abdul Aziz Rajeshkumar, S., Raghunathan, C., & Aziz, N. P. A., 2015. First record, and recovery of Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India. Indian BIRDS. 10 (5): 113–114. S. Rajeshkumar, Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair 744102, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] [Corresponding author.] C. Raghunathan, Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair 744102, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] N. P. Abdul Aziz, Department of Environment and Forests, Andaman and Nicobar Administration, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received on 25 May 2015. edge-tailed Shearwaters Ardenna pacifica are widely Indonesia (Poole et al. 2011). distributed, and breed throughout the tropical Pacific-, We report here the recovery of a live Wedge-tailed Shearwater Wand Indian Oceans (BirdLife International 2015). Two [93] on the Andaman Islands, in May 2015; that it later died in races are recognised: A. p. pacifica breeds in the south-eastern captivity. This is the first specimen recorded for India. Remarkably, part of the northern Pacific Ocean, andA. p. chlororhyncha breeds all the previously documented records from India were also from in the tropical, and sub-tropical Indian-, and Pacific- Oceans (del May. It could be assumed that this species is a spring passage Hoyo et al. 2014). Large breeding colonies of the species exist migrant across the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and in the on oceanic islands between latitudes 35°N and 35°S, such as Indian Ocean. -

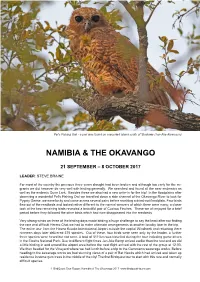

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

SOOTY SHEARWATER | Puffinus Griseus

SOOTY SHEARWATER | Puffinus griseus J Kemper | Reviewed by: PG Ryan © John Paterson Conservation Status: Near Threatened Southern African Range: Waters off Namibia, South Africa Area of Occupancy: Unknown Population Estimate: More than 20 million birds globally Population Trend: Declining Habitat: Islands off South America, Australia, New Zealand, continental shelf, open ocean Threats: Longline, trawl and driftnet fisheries, climate change, harvesting of chicks, marine debris DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE more than 15,000 km in about three weeks on their northward This large, abundant and migratory shearwater breeds on the migration and after spending the austral winter months in Falkland Islands, as well as on islands and some headlands shallow, warm continental shelf waters undertook a two- to off southern Chile, Australia and New Zealand; few also breed three-week return journey (Hedd et al. 2012). on Tristan da Cunha islands (Ryan 2005f, IUCN 2012a). During the non-breeding season, between April and September, Mostly juvenile or non-breeding birds (Brooke 2004) it disperses throughout the Pacific, Atlantic and southern commonly occur along the western and southern coasts of oceans, as far north as Alaska and Japan, and as far south southern Africa throughout the year, particularly during winter as the Antarctic Polar Front. The Sooty Shearwater can travel (Ryan 2005f). They occur singly in oceanic waters, but may be exceptional distances. Birds monitored at breeding colonies found in large flocks over the continental shelf (Ryan & Rose in New Zealand spent the breeding season relatively close 1989, Ryan 1997d). Although reliable population estimates are to the breeding colony, but also foraged along the Antarctic lacking from most breeding colonies (Newman et al. -

2017 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls November 2017 Bird List Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered Common Name Scientific Name Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES Ostriches Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Hottentot Teal Spatula hottentota 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 Pheasants and allies Phasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi H Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos Phoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias minor 1 CICONIIFORMES Storks Ciconiidae Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 1 Eagle-Eye Tours African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 1 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 1 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 1 PELECANIFORMES Ibises, Spoonbills Threskiornithidae African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 1 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia -

Two Spring 2017 Records of Short-Tailed Shearwater Ardenna Tenuirostris from Gujarat, with Notes on Its Identification

50 Indian BIRDS VOL. 14 NO. 2 (PUBL. 28 MARCH 2018) Two spring 2017 records of Short-tailed Shearwater Ardenna tenuirostris from Gujarat, with notes on its identification Trupti Shah, Dhyey Shah, Jagdish Desai & Batuk Bhil Shah, T., Shah, D., Desai, J., Bhil, B., 2018. Two spring 2017 records of Short-tailed Shearwater Ardenna tenuirostris from Gujarat, with notes on its identification. Indian BIRDS 14 (2): 50–52. Trupti Shah, Pratanagar, Vadodara 390004, Gujarat, India. E-mail: [email protected] [TS] Dhyey Shah, Pratanagar, Vadodara 390004, Gujarat, India. [DS] Jagdish Desai [JD] Batuk Bhil, At-Naip, Taluk Mahuva, District Bhavnagar 364290, Gujarat, India. E-mail: [email protected] [BB] Manuscript received on 24 August 2017. n 30 April 2017, while TS and DS were scanning for the Mahuva White-winged Terns Chlidonias leucopterus from a coast (20.05° Oboat, with Latif bhai, at Nal Sarovar (22.80°N, 72.05°E), N, 71.80° E), Gujarat, at 1010 hrs, they immediately noticed an all dark bird, Bhavnagar flying low, with fluttering wing beats, to their left, and a few District, Gujarat. seconds ahead of us. Fortunately, DS and TS took two photos Despite rescue [22, 25] while TS recorded a small video (https://www.youtube. attempts and com/watch?v=phpnCTh4Gw0) before it quickly disappeared. We treatments, it were quite confident that this was a pelagic bird, and suspected did not survive. it to be a petrel. Next morning, after interactions with experts, JD did a post it became clear mortem, and DesaiJagdish that this was some plastic a shearwater: material was either a Sooty found in its 24. -

Status and Occurrence of Wedge-Tailed Shearwater (Puffinus Pacificus) in British Columbia. by Rick Toochin and Louis Haviland. I

Status and Occurrence of Wedge-tailed Shearwater (Puffinus pacificus) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Louis Haviland. Introduction and Distribution The Wedge-tailed Shearwater (Puffinus pacificus) is a widespread polymorphic species found in the warm tropical waters of the Pacific and Indian Ocean (Hamilton et al. 2007, Onley and Scofield 2007). This species breeds on numerous islands (Onley and Scofield 2007). The timing of breeding varies considerably due to the wide range of breeding sites (Onley and Scofield 2007). The southernmost population is found on Kermadec Island and breeds from October to May (Onley and Scofield 2007). There is also a breeding population on the Hawaiian Islands which has different timing and breeds from April to November (Onley and Scofield 2007). A close breeding colony to North America is found on San Benedicto of the Isla Revillagigedo off Mexico (Hamilton et al. 2007, Howell and Webb 2010). This is a regular species in the waters off the Pacific Coast of mainland Mexico south to the Gulf of Mexico (Hamilton et al. 2007, Howell and Webb 2010). Along the west coast of North America, the Wedge-tailed Shearwater is an accidental species with surprisingly few records (Hamilton et al. 2007). This is likely due to this species’ affinity for warm water (Onley and Scofield 2007). In California, there are 7 accepted records by the California Bird Records Committee (Hamilton et al. 2007, Tietz and McCaskie 2014). In Oregon, there are only 2 accepted records by the Oregon Bird Records Committee (OFO 2012). In Washington State, there are 2 records for the state, both were found dead, and both come from Ocean City, Grays Harbor County (Wahl et al. -

BYC-08 INF J(A) ACAP: Update on the Conservation Status

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE NINTH MEETING La Jolla, California (USA) 14-18 May 2018 DOCUMENT BYC-08 INF J(a) UPDATE ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS, DISTRIBUTION AND PRIORITIES FOR ALBATROSSES AND LARGE PETRELS Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) and BirdLife International 1. STATUS AND TRENDS OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS Seabirds are amongst the most globally-threatened of all groups of birds, and conservation issues specific to albatrosses and large petrels led to drafting of the multi-lateral Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). A review of the conservation status and priorities for albatrosses and large petrels was recently published in Biological Conservation (Phillips et al. 2016). There are currently 31 species listed in Annex 1 of the Agreement. Of these, 21 (68%) are classified at risk of extinction, a stark contrast to the overall rate of 12% for the 10,694 bird species worldwide (Croxall et al. 2012, Gill & Donsker 2017). Of the 22 species of albatrosses listed by ACAP, three are listed as Critically Endangered (CR), six are Endangered (EN), six are Vulnerable (VU), six are Near Threatened (NT), and one is of Least Concern (LC). Of the nine petrel species, one is listed as CR, one as EN, four as VU, one as NT and two species as LC. The population trends of ACAP species over the last twenty years (since the mid-1990s) were re-examined in 2017 by the ACAP Population and Conservation Status Working Group (PaCSWG). Thirteen ACAP species (42%) are currently showing overall population declines. -

Feeding Ecology of Short-Tailed Shearwaters: Breeding in Tasmania and Foraging in the Antarctic?

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser l Feeding ecology of short-tailed shearwaters: breeding in Tasmania and foraging in the Antarctic? Henri Weimerskirch*, Yves Cherel CEBC - CNRS, F-79360 Beauvoir, France ABSTRACT- The food, feedlng and physiological ecology of foraging were studied in the short-tailed shearwater Puffinus tenujrostris of Tasmania, to establish whether this species can rely on Antarctic food to fledge its chick. Parents were found to use a 2-fold foraging strategy, on average performing 2 successive short trips at sea of 1 to 2 d duration followed by 1 long trip of 9 to 17 d. These long foraging tnps are the longest yet recorded for any seabird. During short trips the parents tend to lose mass, feed- ing the chick with Australian krill and fish larvae caught in coastal and neritic waters around Tasma- nia. The prey are caught at maximum diving depths of 13 m on average (maximum 30 m).During long trips, adults gain mass and feed their chlcks with a very rich mixture of stomach oil and digested food composed of a high diversity of prey including myctophid fish, sub-Antarctic krill and squids. Prey are probably caught mainly in the Polar Frontal Zone, at least 1000 km south of Tasmania, at maximum depths of 58 m on average (maximum 71 m). Long foraging trips in distant southern waters gave at least twice the yield of trips in close waters but during the former, yield decreased with the time spent for- aging, as indicated by the inverse relationship between time spent forag~ngand adult body condition. -

1 Introduction and Background

PROPOSED 220kV TRANSMISSION LINE FROM OMBURU TRANSMISSION STATION VIA KHAN SUBSTATION TO THE KUISEB TRANSMISSION STATION BIRD IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Assessed by: Assessed for: Chris van Rooyen Consulting 30 Roosevelt Street, Robindale Randburg, 2194 South Africa P O Box 20837 Tel. International: +27824549570 Windhoek Tel. Local: 0824549570 Namibia Fax: 0866405205 Attention: Ms. Van Zyl Email: [email protected] September 2008 i TABLE OF CONTEST 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................. 128 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 128 1.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE .................................................................................................. 129 1.3 PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ............................................................................................ 129 1.4 ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS ................................................................................ 129 1.5 APPROACH TO THE STUDY ........................................................................................... 130 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE BASELINE ENVIRONMENT.................................................. 132 3 IMPACT ASSESSMENT .......................................................................................... 143 3.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 143 3.2 METHODOLOGY EMPLOYED FOR THE IMPACT