The Characteristics of a Holy Cross School Walter E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joy of the Gospel: Path for Renewal in Uncertain Times

2020 RCRI Virtual Conference Joy of the Gospel: Path for Renewal in Uncertain Times 12:00 noon – 4:00 PM (ET) Friday, October 23. 2020 Friday, October 30, 2020 Friday, November 6, 2020 2 2020 RCRI Virtual Conference WELCOME TO THE 2020 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE!! On behalf of the Board of Directors and Staff of the Resource Center for Religious Institutes, I welcome you to the 2020 virtual Conference. Though different from our in-person conferences, we look forward to an enriching conference experience as RCRI begins a new decade of service. We have developed a program of 18 workshop/webinars for the virtual experience with topics that we hope will assist you in addressing the financial and legal issues facing your institutes, especially during these uncertain times. This year’s conference theme is Joy of the Gospel: A Path for Renewal in Uncertain Times reflecting the joy and newness of the Gospel. Pope Francis urges us in New Wine in New Wineskins “to not have fear of making changes according to the law of the Gospel…leave aside fleeting structures – they are not necessary...and get new wineskins, those of the Gospel.” He goes on to say that “one can fully live the Gospel only in a joyous heart and in a renewed heart” (page 31). Fifty-five years ago this October, the Decree on the Renewal of Religious Life, Perfectae caritatis was approved by the Second Vatican Council. The document calls religious and the entire Church to adaptation and renewal of religious life based on a return to the spirit of the founders in the light of the signs of the times. -

Blessed Father Basil Moreau Takes Place in Diocese Pages 10-13 Holy Cross Religious Gather in France for Beatification of Their Founder

50¢ September 30, 2007 Volume 81, No. 35 Red Mass www.diocesefwsb.org/TODAY Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend TTODAYODAY’’SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Mass for legal professionals Blessed Father Basil Moreau takes place in diocese Pages 10-13 Holy Cross religious gather in France for beatification of their founder BY SISTER MARGIE LAVONIS, CSC Indulgence LE MANS, FRANCE — A spirit of joyful anticipation Jubilee Year plenary permeated the environment when hundreds of Holy indulgence extended Cross religious and their colleagues from around the world gathered in Le Mans, France, from Sept. 14-16 Page 2, 4 to celebrate the beatification of their founder, Father Basil Anthony Moreau. The beatification festivities began on Sept. 14, the feast of the Exultation of the Holy Cross. Members of the Holy Cross family and other guests gathered in Memorial feast day front of the parish church in Laigné-en-Belin, the birth- place of Father Moreau. In his opening comments, Oct. 3 dedicated to Holy Cross Father Jean-Guy Vincent, from the St. Mother Theodore Guérin Canadian province of Holy Cross, said, “What could be more fitting for us, the sons and daughters of Basil Page 5 Moreau to gather here to launch the beatification cele- bration?” He spoke of the 60 years that the four congregations of Holy Cross worked to present his cause and said that “after a long and careful examination of the life, activ- Voice from ity and writings of Father Moreau, he was declared venerable by Pope John Paul II, April 12, 2003, and on the congress April 28, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI announced the Eucharistic Congress beatification for Sept. -

Inspiritsisters of the Holy Cross

inSpiritSisters of the Holy Cross 2015annual report Sisters of the Holy Cross table of contents 4 Bearing the torch Dear Friends, Nursing legacy passed on to Saint Mary’s students A new year is well begun, and I am blessed Vol. 4, No. 1 – March 2016 to introduce our 2015 annual report issue 6 inSpirit is published three times annually by of inSpirit. This provides me a wonderful Sister Joysline: the Sisters of the Holy Cross. opportunity for accountability of our Feeling blessed and happy Sisters of the Holy Cross stewardship, along with a forum to thank Founded in 1841 in Le Mans, France, the all who collaborate with us in ministry. The 7 Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Cross many ways you support us help to make our is an international community of women Rebuilding the environment continuing ministry possible and grace-filled. religious whose motherhouse is located in Sisters and students celebrate Arbor Week in Ghana Notre Dame, Indiana. We are called to It is my special pleasure to extend thanks as the three congregations participate in the prophetic mission of Jesus of Holy Cross women — the Sisters of the Holy Cross, the Marianites to witness God’s love for all creation. Our of Holy Cross and the Sisters of Holy Cross — join together to celebrate 10 ministries focus on providing education and health care services, eradicating material 175 years of service to God’s people! Blessed Basil Anthony Moreau, our Standing with Syrian refugees poverty, ending gender discrimination, founder, and Mother Mary of the Seven Dolors, the first sister, stressed and promoting just, mutual relationships the importance of reaching out to women and men to assist the “work of among people, countries and the entire Earth 11 community. -

Bibliography of Holy Cross Sources

Bibliography of Holy Cross Sources General Editor: Michael Connors, C.S.C. University of Notre Dame [email protected] Contributors: Sean Agniel Jackie Dougherty Marty Roers Updated June 2007 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO LOCATION OF ITEMS iii EDITOR’S FOREWORD iv I. FOUNDERS 1-12 A. JACQUES DUJARÍE 1 B. BASIL MOREAU 3 C. MARY OF THE SEVEN DOLORS (LEOCADIE GASCOIN) 12 II. BLESSED 13-20 A. ANDRE (ALFRED) BESSETTE 13 B. MARIE LEONIE PARADIS 20 III. BIOGRAPHIES 21-42 A. BROTHERS 21 B. PRIESTS 30 C. SISTERS 38 D. OTHERS 42 IV. GENERAL HISTORIES 43-60 A. GENERAL ADMINISTRATION` 43 B. INDIVIDUAL COUNTRIES and REGIONS 45 V. PARTICULAR HISTORIES 61-96 A. UNITED STATES 61 B. WORKS OF EDUCATION 68 C. PASTORAL WORKS 85 D. HEALTH CARE SERVICES 89 E. OTHER MINISTRIES 91 VI. APPENDIX OF INDIVIDUAL BIOGRAPHY NAMES 97-99 ii iii KEY TO LOCATION OF ITEMS: CF = Canadian Brothers’ Province Archives CP = Canadian Priests’ Province Archives EB = Eastern Brothers' Province Archives EP = Eastern Priests' Province Archives IP = Indiana Province Archives KC = King’s College Library M = Moreau Seminary Library MP = Midwest Province Archives MS = Marianite Sisters’ Province Archives, New Orleans, LA ND = University of Notre Dame Library SC = Stonehill College Library SE = St. Edward's University Library SHCA = Sisters of the Holy Cross Archives SM = St. Mary’s College Library SW = South-West Brothers’ Province Archives UP = University of Portland Library iii iv EDITOR’S FOREWORD In 1983 I compiled a “Selected Bibliography, Holy Cross in the U.S.A.,” under the direction of Fr. -

National Religious Retirement Office

National Religious Retirement Office 2016 Annual Report Supplement Funding Status In 2016, 539 religious communities provided data to the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO) regarding their assets available for retirement. From this information, the NRRO calculated the extent to which a community is adequately funded for retirement. Shown below are the number of religious institutes at each level of funding and the total number of women and men religious represented by these institutes. Retirement Funding Status and Membership of 539 Participating Religious Institutes Amount Number of Institutes Total Members Funded* Women’s Men’s Total 0–20% 159 36 195 21,046 21–40% 40 10 50 6,179 41–60% 41 12 53 5,693 61–80% 31 24 55 3,503 81–99% 106 39 145 6,438 Adequately 28 13 41 2,012 Total 405 134 539 44,871 *The percentage of retirement funded is based Each symbol represents 500 religious. on designated assets as of December 31, 2016. Women Men Cover photo (from left): Sister Alfonsina Sanchez and care coordinator Sister Michelle Clines, RN, members of the Carmelite Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart of Los Angeles. From the Executive Director Dear Friends, I am pleased to share this supplement to the National Religious Retirement Office 2016 Annual Report. The following pages detail the far-reaching impact of donations to the Retirement Fund for Religious (RFR) collection. (Information regarding contributions to the collection and a fiscal review can be found in the annual report itself, which is available at retiredreligious.org.*) Religious communities combine RFR funding with their own income and savings to meet the current and future needs of senior members. -

Congregation of Holy Cross United States Province of Priests and Brothers

Congregation of Holy Cross United States Province of Priests and Brothers Name Title Address City State Zip Phone Fax E-Mail Please add my address to your mailing list. Please sign me up to receive the bi-monthly Update e-mail newsletter to stay connected to Holy Cross. (Your email address will only be used by Holy Cross; we do not share your information with other organizations.) I’m interested in learning more about: A vocation with Holy Cross International missions Ministries in the United States Thank you for your interest in the Congregation of Holy Cross. Visit us online at HolyCrossUSA.org. Ave Crux Spes Unica Hail the Cross, Our Only Hope The motto of the congregation is Ave Crux, Spes Unica, which means “Hail the Cross, Our Only Hope” — calling on the community to “learn how even the Cross can be borne as a gift.” The symbolic cross and anchors are a “coat of arms” which embodies the ancient Christian symbol of hope, the anchor, with the Cross, creating a simple but powerful representation of our motto. Office of Development P.O. Box 765 Notre Dame, IN 46556-0765 (574) 631-6731 [email protected] HolyCrossUSA.org Office of Development P.O. Box 765 Notre Dame, IN 46556-0765 (574) 631-6731 [email protected] HolyCrossUSA.org Who We Are Fr. StephenKoeth,C.S.C.,NateWills,andPeterPacini,C.S.C. Educators The United States Province of Holy Cross Priests and Brothers is a family of about 500 religious – including men in formation. We live and work in communities large and in the Faith small. -

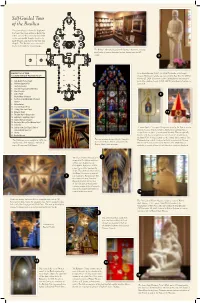

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13 This tour takes you from the baptismal 14 font near the main entrance, down the 12 center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the 16 15 11 Lady Chapel, and then to the west side chapels. The Basilica museum may be 18 17 7 10 reached through the west transept. 9 The Bishops’ Museum, located in the Basilica’s basement, contains pontificalia of various American bishops, dating from the 19th century. 11 6 5 20 19 8 4 3 BASILICA OF THE Saint André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845-1937), founder of St. Joseph’s SACRED HEART FLOOR PLAN Oratory, Montréal, Canada, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on October 17, 2010. The statue of Saint André Bessette was designed 1. Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle by the Rev. Anthony Lauck, C.S.C. (1985). Saint André’s feast day is 2. Holtkamp Organ (1978) 8 January 6. 3. Sanctuary Crossing 2 4. Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross 1 5. Altar of Sacrifice 6. Ambo (Pulpit) 9 7. Original Altar / Tabernacle 8. East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance 9. Tintinnabulum 10. St. Joseph Chapel (Pietà) 11. St. Mary / Bro. André Chapel 2 12. Reliquary Chapel 17 13. The Lady Chapel / Baroque Altar 14. Holy Angels / Guadalupe Chapel 15. Mural of Our Lady of Lourdes 16. Our Lady of Victory / Basil Moreau Chapel 17. Ombrellino 18. Stations of the Cross Chapel / Tomb of A “minor basilica” is a special designation given by the Pope to certain John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C. -

U.S. Catholic Sisters Urge Congress to Support Iran Nuclear Deal

U.S. Catholic Sisters Urge Congress to Support Iran Nuclear Deal Name Congregation City/State Lauren Hanley, CSJ Sisters of St Joseph Brentwood NY Seaford , NY Elsie Bernauer, OP Sisters of St. Dominic Caldwell, NJ Grace Aila, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph NY, NY Sister Lisa Paffrath, CDP Sisters of Divine Providence Allison Park, PA Kathleen Duffy, SSJ Sisters of St. Joseph, Philadelphia Glenside, PA Joanne Wieland, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet St. Paul, MN Sister Cathy Olds, OP Adrian Dominican Lake Oswego, OR Elizabeth Rutherford, osf Srs.of St. Francis of CO Springs Los Alamos, NM charlotte VanDyke, SP Sisters of Providence Seattle, WA Pamela White, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Patricia Hartman, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange Orange, CA Donna L. Chappell, SP Sisters of Providence Seattle , WA Marie Vanston, IHM Srs. Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Scranton, PA Stephanie McReynolds, OSF Sisters of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration CO Springs, CO Joanne Roy, scim Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Saco, ME Lucille Dean, SP Sisters of Providence Great falls, MT Elizabeth Maschka, CSJ Congregation of St. Joseph Concordia, KS Karen Hawkins, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Sister Christine Stankiewicz, C.S.S.F. Felician Sisters Enfield, CT Mary Rogers, DC Daughters of Charity Waco, TX Carmela Trujillo, O.S.F. Sisters of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration CO Springs, CO Sister Colette M. Livingston, o.S.U. ursuline Sisters Cleveland, OH Sister Joan Quinn, IHM Sisters of IHM Scranton, PA PATRICIA ELEY, S.P. SISTERS OF PROVIDENCE SEATTLE, WA Madeline Swaboski, IHM Sisters of IHM Scranton, PA Celia Chappell, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Joan Marie Sullivan, SSJ Sisters of St. -

Ordinations 2012 2 CHOICES Putting the Work of Building God’S Kingdom First Fr

CHOICESFROM THE CONGREGATION OF HOLY CROSS OFFICE OF VOCATIONS VOLUME 33, ISSUE 2 IN THIS ISSUE: Ordinations 2012 2 CHOICES Putting the Work of Building God’s Kingdom First Fr. Matthew C. Kuczora, C.S.C. Ever since he became a deacon, and now a priest, Fr. Matthew The Holy Cross Vocations Team: Fr. Jim Gallagher, C.S.C., and Fr. Drew Gawrych, C.S.C. Kuczora’s fantasy football team has For many years now, we in Holy Cross have celebrated the Ordinations of taken a serious dive. many of our priests on Easter Saturday, placing this special event in the He is on the staff of life of our community right in the midst of the Church’s celebration of the a parish in México, so Sunday has become a busy day resurrection of our Savior, Jesus Christ. Our celebration, then, is not merely for him. His work with seminarians in México also about men receiving the Sacrament of Holy Orders (a reason for rejoicing means that he gets up early and goes to bed late. He in its own right); it becomes a part of the Church’s greater celebration of just does not have the time and energy to follow the the saving mystery of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. NFL like he once did. For the one receiving the Sacrament of Holy Orders, it is a moment in And it is not only Ray Lewis that he misses from which he continues the offer made in his Final Vows to place his life in his life as a college student. -

Charism of Holy Cross Spirituality, Mission and Community Life

CHARISM OF HOLY CROSS SPIRITUALITY, MISSION AND COMMUNITY LIFE A "charism" is a gift of the Spirit that is given individually or collectively for the common good and the building up of the Church. Inherent in this gift is a particular perception of the image of Jesus Christ and of the Gospel. It is, therefore, a source of inspiration, a dynamic commitment, and a capacity for realization. THE CHARISM OF HOLY CROSS Basile Moreau was a man open to the world of his time, namely 19th -century France. He knew the effects of the revolutionary change and social upheaval of his century. He also experienced the often violent hostility towards religion and the Church, the growth of secularism, and widespread dechristianization. He wanted to be present to a society in search of itself. He felt called to work for the restoration of the Christian faith and through it for a regeneration of society. He was ready to undertake anything for the salvation of individuals, to lead them or bring them back to Jesus Christ. He participated in the work of Catholic renewal by his bold response to the wide range of needs both in the Church and in society. He asked his religious to "be ready to undertake anything ... to suffer everything and to go wherever obedience calls in order to save souls and extend the kingdom of Jesus Christ on earth” (Rule on Zeal). He even went so far as to say that if a postulant or a novice did not have that inner zeal to work for the salvation of souls, he was not fit for Holy Cross. -

Christian Education by Bl. Basil Moreau

Christian Education By Blessed Basil Anthony M. Moreau The Holy Cross Institute AT ST. EDWARD’S UNIVERSITY Editor’s Note First published in 1856, Christian Education is a manuscript by Reverend Basil Anthony M. Moreau, founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross. In this manuscript, Father Moreau attempted to outline the ideals and the goals of a Holy Cross education as he saw them. These ideals were used in setting up the school in Le Mans, France, that bore the name Our Lady of Holy Cross. Part One of the original text, Teachers and Students, is presented in its entirety. Part Two, dealing with the establishment of a school in the France of Father Moreau’s day, provides practical guidelines for maintaining a school and directives regarding content and instruction. This edition includes brief excerpts from the final part (the only difference from the earlier version), which deals with the teaching of religion and the Christian formation of students. Grateful acknowledgement is made to the South-West Province, Congregation of Holy Cross for making Christian Education available in English to the Congregation, and in particular to Brother Edmund Hunt, CSC, for the initial translation, completed in 1986. That edition was ably edited by Brother Franklin Cullen, CSC, and Brother Donald Blauvelt, CSC. The new excerpts included in this edition are from a subsequent translation of Christian Education by Sister Anna Teresa Bayhouse, CSC, completed in December 2002. To this sesquicentennial edition of Christian Education are appended a readers’ guide and materials for further reflection. Grateful acknowledgement goes to the contributions of Brother Joel Giallanza, CSC, Brother Thomas Dziekan, CSC, and Brother Robert Lavelle, CSC, in the preparation of these latter materials. -

Saint Mary's College Editorial Style and Reference Guide

Updated 7/17/17 Saint Mary’s College Editorial Style and Reference Guide Introduction This editorial stylebook covers matters of style specific to Saint Mary’s College, as well as a review of common problems of grammar and usage. The intent of the style guide is to provide consistency in writing by the Division of College Relations, but can be used by other offices on campus as well. This guide, first created in 2013 by members of the Division of College Relations, is a living document and can be added to or revised upon consideration by the Style Committee (currently made up of Haleigh Ehmsen, media relations associate; Megan Eifler, assistant director of marketing, graduate programs; Claire Kenney, assistant director of communications for development; Christine Swarm, director of annual giving, Mary Firtl, senior graphic designer, and Kathe Brunton, freelance writer). Suggestions for revisions should be submitted to Haleigh at [email protected]. References for compilation of this stylebook are listed below: The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th ed. (CMS 16) The 2012 Associated Press Stylebook (AP) Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed. (online version at m-w.com) Saint Mary’s College Bulletin 2011–2012 (or most recent edition) Stylebook and Reference Manual of the Sisters of the Holy Cross* Agency ND Style Guide (NDSM, online version at agency.nd.edu) For general guidance on matters not covered here, consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th ed. (CMS 16). In the case of press releases, consult The Associated Press Stylebook. *Most of the style for the Catholic Terminology and Congregational Information sections of this stylebook is borrowed, with permission, from the Stylebook and Reference Manual of the Sisters of the Holy Cross for use by Saint Mary’s College.