The Testament of Job

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holy Trinity & St. Michael

Kewaskum Catholic Parishes of Holy Trinity & St. Michael Staff Holy Trinity & St. Michael Shared Pastor www.kewaskumcatholicparishes.org Rev. Jacob A. Strand Holy Trinity Office –Ext. 104 Deacon: Rev. Mr. Ralph Horner St. Michael Office – 262-334-5270 Cell Phone – 262-343-1795 [email protected] Hours: Wednesdays 6:30pm—8pm Holy Trinity Church 305 Main Street P.O. Box 461 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-626-2860 Fax – 262-626-2301 Dir. of Admin Services– Mrs. Nancy Boden Ext. 106 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Ext. 105 [email protected] St. Michael Church 8883 Forest View Road Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone – 262-334-5270 [email protected] Shared Admin. Assistant – Mrs. Jenni Bolek Holy Trinity School 305 Main Street P.O. Box 464 Kewaskum, WI 53040 Phone 262-626-2603 Website: www.htschool.net Principal – Mrs. Amanda Longden Ext. 101 [email protected] School Secretary—Mrs. Angela Schickert Ext. 100—[email protected] Faith Formation Program Phone 262-626-2650 WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE DAILY MASS SCHEDULE Dir. of Faith Formation/Coordinator for K—8th Grade—Mrs. Mary Breuer Saturday 4:00 p.m.—St. Michael Tuesdays 5:00 p.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] Sunday 7:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Wednesdays 6:30 a.m.—Holy Trinity Associate Director/Coordinator for H.S. Sunday 9:00 a.m.—St. Michael Thursdays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity Youth Ministry—Mrs. Jessica Herriges Sunday 11:00 a.m.—Holy Trinity Fridays 7:45 a.m.—Holy Trinity [email protected] SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION EUCHARSTIC ADORATION Joint Pastoral Council Chair Mrs. -

President's Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families

President’s Monthly Letter Feast of St. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels September 2020 Dear Guardian Families, Happy Feast of Sts. Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels! Yesterday we celebrated our patronal feast and the 3rd anniversary of the dedication of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Chapel. As our fourth year is now underway, we can look back and celebrate the many accomplishments of SMA in the past and look forward to our exciting future together, confident that our patron, St. Michael, will defend us in the battle. Whenever I visit the doctor, there are four words I never like to hear: “Now this may hurt.” That message brings about two responses in me, the first is one of dread… it means I’m going to be experiencing something I really don’t want! Secondly, I brace in anticipation of what is about to happen; I’m able to make myself ready for the event. September is the month of Our Lady of Sorrows (in Latin, the seven “dolors”). When Mary encountered Simeon in the temple, she heard the same message in a more intense form, “this is going to hurt.” The prophet told her, A sword will pierce through your own soul. Mary, a new mother still in wonder at the miraculous birth of her child, now hears that her life is going to be integrally tied to his sufferings. So September is always a month linked to compassion; the compassion Mary had for her son and has for us. It is also a reminder of the compassion we can have for each other. -

Who Were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430

414 Mondriaan: Who were the Kenites? OTE 24/2 (2011): 414-430 Who were the Kenites? MARLENE E. MONDRIAAN (U NIVERSITY OF PRETORIA ) ABSTRACT This article examines the Kenite tribe, particularly considering their importance as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the Kenites, and the Midianites, were the peoples who introduced Moses to the cult of Yahwism, before he was confronted by Yahweh from the burning bush. Scholars have identified the Cain narrative of Gen 4 as the possible aetiological legend of the Kenites, and Cain as the eponymous ancestor of these people. The purpose of this research is to ascertain whether there is any substantiation for this allegation connecting the Kenites to Cain, as well as con- templating the Kenites’ possible importance for the Yahwistic faith. Information in the Hebrew Bible concerning the Kenites is sparse. Traits associated with the Kenites, and their lifestyle, could be linked to descendants of Cain. The three sons of Lamech represent particular occupational groups, which are also connected to the Kenites. The nomadic Kenites seemingly roamed the regions south of Palestine. According to particular texts in the Hebrew Bible, Yahweh emanated from regions south of Palestine. It is, therefore, plausible that the Kenites were familiar with a form of Yahwism, a cult that could have been introduced by them to Moses, as suggested by the Kenite hypothesis. Their particular trade as metalworkers afforded them the opportunity to also introduce their faith in the northern regions of Palestine. This article analyses the etymology of the word “Kenite,” the ancestry of the Kenites, their lifestyle, and their religion. -

St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY

SEPTEMBER Activity 6 St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us PRAYER BOARD ACTIVITY Age level: All ages Recommended time: 10 minutes What you need: St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book), SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel (optional), colored pencils and/or markers, and scissors Activity A. Explain to your students that we have been learning that the Devil and his fallen angels tempt us to sin. We can pray a special, very powerful prayer to St. Michael to help us combat these evil spirits. St. Michael is not a saint, but an archangel. The archangels are leaders of the other angels. According to both Scripture and Catholic Tradition, St. Michael is the leader of the army of God. He is often shown in paintings and iconography in a scene from the book of Revelation, where he and his angels battle the dragon. He is the patron of soldiers, policemen, and doctors. B. Have your students turn to St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us (page 158 in the students' activity book) and pray together the prayer to St. Michael the Archangel. You may wish to play a sung version of the prayer, which you can find at SophiaOnline.org/StMichaeltheArchangel. C. Finally, have your students color in the St. Michael shield and attach it to their prayer boards. © SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS St. Michael the Archangel Defends Us St. Michael the Archangel protects us against danger and the Devil. He is our defense and our shield and the Church has given us a special prayer so that we can ask him for help. -

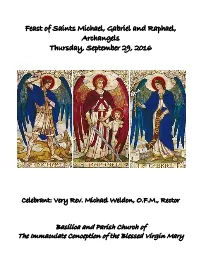

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016

Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels Thursday, September 29, 2016 Celebrant: Very Rev. Michael Weldon, O.F.M., Rector Basilica and Parish Church of The Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary The Angelus V. The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary: R. And she conceived by the Holy Spirit. Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. V. Behold the handmaid of the Lord: R. Be it done unto me according to thy word. Hail Mary... V. And the word was made flesh: R. And dwelt among us. Hail Mary... V. Pray for us, O Holy Mother of God. R. That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ. Pour forth, we beseech thee, O Lord, thy grace into our hearts, that we to whom the incarnation of Christ Thy Son was made known by the message of an angel, may by His Passion and Cross be brought to the glory of His resurrection; through the same Christ our Lord. Amen. Entrance Chant Michael, Prince of All the Angels Michael, prince of all the angels, Gabriel, messenger to Mary, While your legions fill the sky, Raphael, healer, friend and guide, All victorious over Satan, All you hosts of guardian angels Lift your flaming sword on high; Ever standing by our side, Shout to all the seas and heavens: Virtues, Thrones and Dominations, Now the morning is begun; Raise on high your joyful hymn, Now is rescued from the dragon Principalities and Powers, She whose garment is the sun! Cherubim and Seraphim! Mighty champion of the woman, Mighty servant of her Lord, Come with all your myriad warriors, Come and save us with your sword; Enemies of God surround us: Share with us your burning love; Let the incense of our worship Rise before His throne above! Gloria Gospel Acclamation Sanctus Mystery of Faith Amen Agnus Dei Prayer to St. -

May 20Th, 2021

May 20th, 2021 Pentecost and Paulist Ordination The feast of Pentecost is this Sunday, May 23rd. As the Holy Spirit breathes new life into the hearts of the faithful, we're excited to celebrate with a little more togetherness! Pentecost is a yearly reminder to share Christ's light, and gives us an opportunity to consider how we can bring God's ministry into the world. This spirit of ministry provides us with the perfect backdrop to welcome two new priests into the Paulist Fathers! The staff of St. Paul's has also been focused on ministry this week. With the world ever so slowly opening back up, St. Paul's looks forward to seeing you! Keep an eye out for events as we rebuild the ministries that make up our vibrant and thriving community. Join us in celebrating the priestly ordination of Deacon Michael Cruickshank, CSP, and Deacon Richard Whitney, CSP, this Saturday, May 22nd at 11AM at St. Paul the Apostle Church! Bishop Richard G. Henning will be the principal celebrant. The public is welcome to attend the mass! In addition, it will be broadcast live at paulist.org/ordination as well as on the Paulist Fathers’ Facebook page and YouTube channel. If you can't attend the ceremony, our two new Paulist Fathers will be saying their First Masses at the 10AM and 5PM masses on Sunday, May 23rd. However you're able to participate, we hope you will join us in celebrating these men as they journey into God's ministry! Ordination 2021 A Note from Pastor Rick Walsh This weekend we celebrate the presbyteral ordination of two Paulists, Michael Cruickshank and Richard Whitney. -

2 KINGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza

2 KINGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza Editorial Board Mary Ann Beavis Carol J. Dempsey Gina Hens-Piazza Amy-Jill Levine Linda M. Maloney Ahida Pilarski Sarah J. Tanzer Lauress Wilkins Lawrence WISDOM COMMENTARY Volume 12 2 Kings Song-Mi Suzie Park Ahida Calderón Pilarski Volume Editor Barbara E. Reid, OP General Editor A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. © 2019 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, except brief quotations in reviews, without written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, MN 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Title: 2 Kings / Song-Mi Suzie Park ; Ahida Calderón Pilarski, volume editor ; Barbara E. Reid, OP, general editor. Other titles: Second Kings Description: Collegeville : Liturgical Press, 2019. | Series: Wisdom commentary ; Volume 12 | “A Michael Glazier book.” | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019019581 (print) | LCCN 2019022046 (ebook) | ISBN -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question. -

Midian -A Land Or a League ?

MIDIAN -A LAND OR A LEAGUE ? BY WILLIAM J. DUMBRELL Sydney The biblical accounts of the activities of the Midianites or related groupings at the end of the Late Bronze Age period present them as a seemingly ubiquitous people who are found not only in the Horeb/Sinai region as well as in Egypt, but also astride the great north-south trade routes, in the plains of Moab, and apparently, if the habitat of Balaam is to be placed at or near the ancient Pitru, extending, at least in their influence, as far as the Euphrates River itself (Num. xxii 5). It is obvious that, even to the biblical writers, they were a curious and a puzzling entity, about whom little was known directly, and who were confused or amalgamated with many associated or semi-related peoples. What is said of them is said in relation to other groups and to Israel itself, in all of whom the biblical writers naturally were much more interested. Associated with Israel in the formative national period of the Exodus and wilderness wanderings, the Midianites demonstrably had left their sociological stamp on many of Israel's early institutions, while at the same time they infiltrated to some degree their contiguous Israelite neighbours in the south Palestine and Transjordanian areas. But they are also related to or associated with the Edomites, Kenites, Ishmaelites, Hagarites and Kenizzites while there are at least con- nections with Amalekites and Moabites, and perhaps with Ammo- nites. All in all, they are an amorphous and complex grouping. To explain this complexity of biblical presentation, over sixty years ago Paul HAUPT opined, "Midian ist nicht der Name eines arabischen Stammes sondern .. -

Weekly Sermon Discussion Guide Midian RESCUED

Weekly Sermon Discussion Guide January 12, 2020 Midian RESCUED Exodus 2:11 EXPLORING THE SERMON • What did you hear? • What did you think or feel about what you heard? • What is one thing you can take away from the sermon this week? KEY VERSES 11 One day, after Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and saw their forced labor. He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his kinsfolk. 12 He looked this way and that, and seeing no one he killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand. 15 When Pharaoh heard of it, he sought to kill Moses. But Moses fled from Pharaoh. He settled in the land of Midian, and sat down by a well. 16 The priest of Midian had seven daughters. 20 He said to his daughters, “Where is he? Why did you leave the man? Invite him to break bread.” 21 Moses agreed to stay with the man, and he gave Moses his daughter Zipporah in marriage. 22 She bore a son, and he named him Gershom; for he said, “I have been an alien[a] residing in a foreign land.” Exodus 2:11-12; 15-16; 20-22 DISCUSSION AND REFLECTION In this passage, Moses has been forced to flee to Midian, from Pharoah who wants to kill him. Moses, with a heart of justice, killed an Egyptian taskmaster who was treating a Hebrew unjustly. It is hard for us to grasp that slavery is more alive today in the world than any point in history, and that we benefit from it every day through the products we buy and how we spend our money. -

Lesson 13 – Wisdom Literature Text: Job; Psalms; Proverbs

Lesson 13 – Wisdom Literature Text: Job; Psalms; Proverbs; Ecclesiastes; Song of Solomon Job: The book of Job describes a man, Job, who deals with the aftermath of great calamity in his life. Job was a righteous man, and Satan challenged the reason for his righteousness to God, arguing that Job only was faithful because of the blessings God provided him. God allowed Satan to afflict Job in various ways, taking away his wealth, children, and good health. Job’s friends came to comfort him, but eventually they and Job began to argue about the reason that Job was afflicted in the first place (they believed that he was being punished for sin). The ultimate lesson is that one’s relationship with God must constant, not affected by the trials of life. Job and his friends learned this lesson, amongst many others. At the end of the book, God restored Job’s possessions and family (and even more). Psalms: The book of Psalms is simply a collection of Jewish songs which cover a variety of topics, including praise to the Lord, historical events, prayers for help, thanksgiving, and even prophecy. Many of the psalms were written by David, who wrote psalms to during many events of his life such as his sin with Bathsheba (51), his deliverance from Saul (18), and others. Other authors include the sons of Korah (the Levite who rebelled in Numbers 16), Asaph (a director of singers in the temple), Solomon, and even Moses. Perhaps the most important psalms are those that prophecy about Jesus’s coming, death, resurrection, and the establishment of His church (for good examples, see Psalms 2 and 22). -

Testament of Job

Testament of Job the blameless, the sacrifice, the conqueror in many contests. Book of Job, called Jobab, his life and the transcript of his Testament. Translated by M. R. James -Revised English by Jeremy Kapp- Chapter 1 1 On the day he became sick and (he) knew that he would have to leave his bodily abode, he called his seven sons and his three daughters together and spoke to them as follows: 2 “Form a circle around me, children, and hear, and I shall relate to you what the Lord did for me and all that happened to me. 3 For I am Job your father. 4 Know then my children, that you are the generation of a chosen one and take heed of your noble birth. 5 For I am of the sons of Esau. My brother is Nahor, and your mother is Dinah. By her have I become your father. 6 For my first wife died with my other ten children in bitter death. 7 Hear now, children, and I will reveal to you what happened to me. 8 I was a very rich man living in the East in the land Ausitis, (Utz) and before the Lord had named me Job, I was called Jobab. 9 The beginning of my trial was like this. Near my house there was the idol of one worshipped by the people; and I saw constantly burnt offerings brought to him as a god. 10 Then I pondered and said to myself: “Is this he who made heaven and earth, the sea and us all? How will I know the truth?” 11 And in that night as I lay asleep, a voice came and called: “Jobab! Jobab! rise up, and I will tell you who is the one whom you wish to know.