International Journal of Media Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009)

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009) New Delhi 151 Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Chairman: Mr. Justice G. N. Ray Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANIZATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPER Shri Vishnu Nagar Editors Guild of India, All India Nai Duniya, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Uttam Chandra Sharma All India Newspaper Editors’ Muzaffarnagar Conference, Editors Guild of India, Bulletin, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Vijay Kumar Chopra All India Newspaper Editors’ Filmi Duniya, Conference, Editors Guild of India, Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Sheetla Singh Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Ms. Suman Gupta Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Saryu Tat Se, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Editors of English Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Yogesh Chandra Halan Editors Guild of India, All India Asian Defence News, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri K. Sreenivas Reddy Indian Journalists Union, Working Visalaandhra, News Cameramen’s Association, Andhra Pradesh Press Association Shri Mihir Gangopadhyay Indian Journalists Union, Press Freelancer, (Ganguly) Association, Working News Bartaman, Cameramen’s Association West Bengal Shri M.K. Ajith Kumar Press Association, Working News Mathrubhumi, Cameramen’s Association, New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Joginder Chawla Working News Cameramen’s Freelancer Association, Press Association, Indian Journalists Union Shri G. -

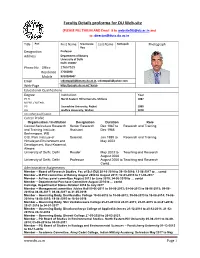

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Prof. First Name Sreenivasa Last Name Kottapalli Photograph Rao Designation Professor Address Department of Botany University of Delhi Delhi 110007 Phone No Office 27667525 Residence 27666898 Mobile 9313294607 Email [email protected], [email protected] Web-Page http://people.du.ac.in/~ksrao Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. North Eastern Hill University, Shillong 1987 M.Phil. / M.Tech. PG Saurashtra University, Rajkot 1980 UG Andhra University, Waltair 1978 Any other qualification Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Central Sericulture Research Senior Research Dec 1987 to Research and Training and Training Institute, Assistant Dec 1988 Berhampore, WB G.B. Pant Institute of Scientist Jan 1989 to Research and Training Himalayan Environment and May 2003 Development, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora University of Delhi, Delhi Reader May 2003 to Teaching and Research August 2008 University of Delhi, Delhi Professor August 2008 to Teaching and Research Contd.. Administrative Assignments Member – Board of Research Studies, Fac of Sci (DU) 30-10-2014 to 29-10-2016; 13-06-2017 to …contd Member – M.Phil committee of Botany August 2008 to August 2011; 12-03-2015 to 11-03-2017 Member – Ad-hoc panel committee August 2012 to June 2015; 24-06-2015 to … contd Member – Departmental Purchase Committee August 2014 to … contd Incharge, Departmental Stores October -

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2012-2013 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT (%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 67059 0.002525667 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 579134 0.021812132 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1172263 0.044151362 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 373181 0.01405525 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 390958 0.014724791 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 172950 0.006513878 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 366211 0.013792736 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 398436 0.015006438 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 180263 0.00678931 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 265972 0.010017399 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 4172 0.000157132 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 297035 0.011187336 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410280 HELAPURI NEWS TELUGU DAILY(E) 67795 0.002553387 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 152550 0.005745545 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410405 VASISTA TIMES TELUGU DAILY(E) 62805 0.002365447 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 369397 0.013912732 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 239960 0.0090377 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 209853 -

Resignations and Retirements

CCUURRRREENNTT AAFFFFAAIIRRSS JJUUNNEE 22001166 -- RREESSIIGGNNAATTIIOONNSS http://www.tutorialspoint.com/current_affairs_june_2016/resignations_and_retirements.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com News 1 - Nikesh Arora resigns as the SoftBank President and COO The SoftBank Group Corporation President Nikesh Arora resigned from the Telecom Giant effective June 22nd. Mr Arora had taken over as the President and COO of SoftBank in May 2015. He will assume an advisory role, effective July 1. The SoftBank Group has named Ken Miyauchi as its new President and Chief Operating Officer after the resignation of Nikesh Arora. SoftBank said Arora and Chairman and Chief Executive Masayoshi Son had disagreed over when Arora would replace Son as the head of the group. Arora was a former Chief Business Officer at Google Inc. News 2 - Anju Bobby George Resigned as the President of the Kerala Sports Council Olympian Anju Bobby George resigned as the President of the Kerala Sports Council after she felt humiliated by the State's Sports Minister, EP Jayarajan, who's accused her of corruption. The job was assigned to her by the previous Congress led government in the State eight months ago. She won the Gold Medal at the IAAF World Athletics Final in 2005 and won the bronze medal clearing 6.49 meters at the 2002 Commonwealth Games at Manchester. She also won the Gold Medal at the Asian Games in Busan. She was awarded the Arjuna Award in year 2002. News 3 - Aveek Sarkar Resigns as the Editor-In-Chief of ABP Group of Publications Mr. Aveek Sarkar has stepped down as the Chief Editor of ABP Pvt. -

Download Coverage File

CONFIDENTIAL Digisakshar.org Launch PUBLIC RELATIONS & COMMUNICATIONS – PROJECT REPORT 5th August-20th August 2020 Submitted by ADRIFT COMMUNICATIONS & INFLUENCER MARKETING www.adriftcommunications.com COVERAGE INDEX NEW DELHI S. No. Date Publication 1 13th August, 2020 The Economic Times (online) 2 13th August, 2020 Financial Express (online) 3 13th August, 2020 Deccan Herald (online) 4 13th August, 2020 Punjab Kesari (online) 5 11th August, 2020 Dainik Jagran (online) 6 05th August, 2020 www.Expresscomputer.in 7 05th August, 2020 www.crn.in 8 05th August, 2020 www.CSRJournal.in 9 05th August, 2020 www.CSRMandate.org 10 05th August, 2020 www.humancapitalonline.com 11 05th August, 2020 www.indiaeducationdiary.in 12 05th August, 2020 www.indiacsr.in 13 06th August, 2020 www.sightsinplus.com 14 07th August, 2020 www.ciol.com 15 07th August, 2020 www.crossbarriers.org 16 07th August, 2020 Deshbandhu 17 08th August, 2020 Aaj 18 08th August, 2020 Virat Vaibhav 19 08th August, 2020 Dilli Dil Se (Facebook pg) www.adriftcommunications.com 20 13th August, 2020 Thodkyaat.com (Marathi) LUCKNOW S. No. Date Publication 1 12th August, 2020 Hindustan Times 2 12th August, 2020 Pioneer 3 07th August, 2020 Dainik Jagran 4 12th August, 2020 Rashtriya Sahara 5 14th August, 2020 Aaj 6 07th August, 2020 Spasht Awaz 7 06th August, 2020 Voice of Lucknow 8 06th August, 2020 Nyayadheesh 9 06th August, 2020 Everyday News 10 06th August, 2020 Daily News Activist 11 06th August, 2020 Swatantra Bharat 12 06th August, 2020 Rashtriya Prastavana 13 10th August, 2020 Tarun Mitra www.adriftcommunications.com INDORE S. No. -

1 Jyotirmoy Thapliyal, Senior Staff Correspondent, the Tribune, Dehradun 2.Dhananjay Bijale, Senior Sub-Editor, Sakal, Pune 3

1 Jyotirmoy Thapliyal, senior staff correspondent, The Tribune, Dehradun 2.Dhananjay Bijale, senior sub-editor, Sakal, Pune 3. Vaishnavi Vitthal, reporter, NewsX, Bangalore 4.Anuradha Gupta, web journalist, Dainik Jagran, Kanpur 5. Ganesh Rawat, field reporter, Sahara Samay, Nainital 6.Gitesh Tripathi, correspondent, Aaj Tak, Almora 7. Abhishek Pandey, chief reporter, Sambad, Bhubaneswar 8. Vipin Gandhi, senior reporter, Dainik Bhaskar, Udaipur 9. Meena Menon, deputy editor, The Hindu, Mumbai 10. Sanat Chakraborty, editor, Grassroots Options, Shillong 11. Chandan Hayagunde, senior correspondent, The Indian Express, Pune 12. Soma Basu, correspondent, The Statesman, Kolkata 13. Bilina M, special correspondent, Mathrubhumi, Palakkad 14. Anil S, chief reporter, The New Indian Express, Kochi 15. Anupam Trivedi, special correspondent, Hindustan Times, Dehradun 16. Bijay Misra, correspondent, DD, Angul 17. P Naveen, chief state correspondent, DNA, Bhopal 18. Ketan Trivedi, senior correspondent, Chitralekha, Ahmedabad 19. Tikeshwar Patel, correspondent, Central Chronicle, Raipur 20. Vinodkumar Naik, input head, Suvarna TV, Bangalore 21. Ashis Senapati, district correspondent, The Times of India, Kendrapara 22. Appu Gapak, sub-editor, Arunachal Front, Itanagar 23. Shobha Roy, senior reporter, The Hindu Business Line, Kolkata 24. Anupama Kumari, senior correspondent, Tehelka, Ranchi 25. Saswati Mukherjee, principal correspondent, The Times of India, Bangalore 26. K Rajalakshmi, senior correspondent, Vijay Karnataka, Mangalore 27. Aruna Pappu, senior reporter, Andhra Jyothy, Vizag 28. Srinivas Ramanujam, principal correspondent, Times of India, Chennai 29. K A Shaji, bureau chief, The Times of India, Coimbatore 30. Raju Nayak, editor, Lokmat, Goa 31. Soumen Dutta, assistant editor, Aajkal, Kolkata 32. G Shaheed, chief of bureau, Mathrubhumi, Kochi 33. Bhoomika Kalam, special correspondent, Rajasthan Patrika, Indore 34. -

Media Accreditation Index

LOK SABHA PRESS GALLERY PASSES ISSUED TO ACCREDITED MEDIA PERSONS - 2020 Sl.No. Name Agency / Organisation Name 1. Ashok Singhal Aaj Tak 2. Manjeet Singh Negi Aaj Tak 3. Rajib Chakraborty Aajkaal 4. M Krishna ABN Andhrajyoti TV 5. Ashish Kumar Singh ABP News 6. Pranay Upadhyaya ABP News 7. Prashant ABP News 8. Jagmohan Singh AIR (B) 9. Manohar Singh Rawat AIR (B) 10. Pankaj Pati Pathak AIR (B) 11. Pramod Kumar AIR (B) 12. Puneet Bhardwaj AIR (B) 13. Rashmi Kukreti AIR (B) 14. Anand Kumar AIR (News) 15. Anupam Mishra AIR (News) 16. Diwakar AIR (News) 17. Ira Joshi AIR (News) 18. M Naseem Naqvi AIR (News) 19. Mattu J P Singh AIR (News) 20. Souvagya Kumar Kar AIR (News) 21. Sanjay Rai Aj 22. Ram Narayan Mohapatra Ajikali 23. Andalib Akhter Akhbar-e-Mashriq 24. Hemant Rastogi Amar Ujala 25. Himanshu Kumar Mishra Amar Ujala 26. Vinod Agnihotri Amar Ujala 27. Dinesh Sharma Amrit Prabhat 28. Agni Roy Ananda Bazar Patrika 29. Diganta Bandopadhyay Ananda Bazar Patrika 30. Anamitra Sengupta Ananda Bazar Patrika 31. Naveen Kapoor ANI 32. Sanjiv Prakash ANI 33. Surinder Kapoor ANI 34. Animesh Singh Asian Age 35. Prasanth P R Asianet News 36. Asish Gupta Asomiya Pratidin 37. Kalyan Barooah Assam Tribune 38. Murshid Karim Bandematram 39. Samriddha Dutta Bartaman 40. Sandip Swarnakar Bartaman 41. K R Srivats Business Line 42. Shishir Sinha Business Line 43. Vijay Kumar Cartographic News Service 44. Shahid K Abbas Cogencis 45. Upma Dagga Parth Daily Ajit 46. Jagjit Singh Dardi Daily Charhdikala 47. B S Luthra Daily Educator 48. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

ANNUAL REPORT 2013-2014 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE EDUCATION AND RESEARCH KOLKATA In this year’s report Preface 04 1. The IISER Kolkata Community 09 1.1 Staff Members 10 1.2 Achievements of Staff Members 19 1.3 Student Achievements 21 1.4 Insti tute Achievement 24 2. Administrative Report 25 3. Research & Teaching 29 3.1 Acti viti es 30 3.1.1 Department of Biological Sciences 30 3.1.2 Department of Chemical Sciences 34 3.1.3 Department of Earth Sciences 36 3.1.4 Department of Mathemati cs and Stati sti cs 42 3.1.5 Department of Physical Sciences 44 3.1.6 Center of Excellence in Space Sciences India (CESSI) 46 3.2 Research and Development Acti viti es 48 3.3 Sponsored Research 50 3.4 Equipment Procured 73 3.5 Library 77 3.6 Student Enrolment 78 3.7 Graduati ng Students 79 4. Seminars & Colloquia 85 4.1 Department of Biological Sciences 86 4.2 Department of Chemical Sciences 88 4.3 Department of Earth Sciences 89 4.4 Department of Mathemati cs and Stati sti cs 91 4.5 Department of Physical Sciences 92 4.6 Center of Excellence in Space Sciences 96 5. Publications 97 5.1 Publicati ons of Faculty Members 98 5.1.1 Department of Biological Sciences 98 5.1.2 Department of Chemical Sciences 100 5.1.3 Department of Earth Sciences 106 5.1.4 Department of Mathemati cs and Stati sti cs 107 5.1.5 Department of Physical Sciences 108 5.2 Student Publicati ons 112 5.3 Staff Publicati ons 112 6. -

Journalists and Trade Unions in Kolkata's Newspapers: Whither Collective Action?

IJMS Vol.1 No.1 International Journal of Media Studies July 2019 Journalists and Trade Unions in Kolkata’s Newspapers: Whither collective action? Suruchi Mazumdar O.P. Jindal Global University Abstract: This paper explores trade unions’ relationship to the notions of journalistic professionalism through a historical study of journalists and newsworkers’ unions in newspapers in the east Indian city of Kolkata. Much of the literature on the challenges that contemporary journalists face accords with experiences in India: the proliferation of digital ICTs; media concentration and conglomeration; and the rise of contractual employment and decreased collective power of journalists, which have been associated with a loss of bargaining power in newsrooms and the erosion of professional autonomy. A section of scholarship of journalistic labour tends to perceive unionised workforce as a necessary response to the challenges of market economy. Yet, the ability of journalism to exert control over its field of practice vis- a-vis external interests (Waisbord, 2013, p. 56) has long been argued to be an important concept in the narrative of the profession. Arguably, the notion of journalism’s “differentiation” from “external interests” has been challenged in a “hybrid digital environment” with people engaging with news in different forms “as audiences, users, producers, sources, experts, or citizens”. This further complicates journalist unions’ responses to the notions of professionalism. In India, a developing economy where organised labour largely enjoyed democratic rights and freedoms in the era after Independence from British colonial rule, the unions of journalists and other newspaper employees were engaged in a long-drawn struggle for structured wages as recommended by a statutory wage board.