Erasing the Lines Between Leisure and Labor: Creative Work in the Comics World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

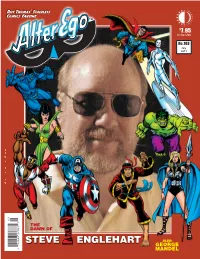

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Superhero Team Up!

Superhero Team up! Working together to teach intellectual property to our students Our Heroes Maria Burchill, The Bookkeeper John Meier, The Cybrarian The story so far... 1. Overview of intellectual property 1. Create your own superhero 1. Ideas for presenting a program like this Golden Age of Comics Silver Age of Comics How do the creators/artists of superheroes protect their creativity and innovation? ● How would you protect your original drawing, story, or theme song? ● How about your invention of a superhero gadget? ● What about the name of your hero? Copyright protects ‘ the authors of “original works of authorship,” including literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and certain other intellectual works’ www.copyright.gov Copyright 1938 - rights sold for $130 1948 - creators lose to DC 1975 - creators lose but get benefits 1999 - estates renegotiate 2013 - DC sole owner Trademarks “A trademark is a word, phrase, symbol or design, or a combination thereof, that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others.” US Patent and Trademark Office (www.uspto.gov) Patents “exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United States or importing the invention into the United States” - U.S. Patent Office Copycats are literally Villains! Using someone else’s work without giving them credit is dishonest and wrong (Schlipp and Kocis) Create your own superhero Draw a costume Write a ★Name ★Secret Origin ★Powers ★Gadgets Congratulations! You are now a copyright holder Trademarks need to be used on a product or service in order to file. Patents applications must actually work (no time machines!) Tips for your own program ❏Identify partners in superheroes and IP (local artists and comic store owners) ❏Prepare your presentation content (more video clips for younger audiences) ❏Promote, promote, promote ❏Bring plenty of supplies, comics, & freebies In our next exciting episode.. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Oasis Digital Studios and Apex Comics Group Partner with Comic-Book Industry Legends for New Multimedia Experiences and Nfts

Oasis Digital Studios and Apex Comics Group partner with Comic-Book Industry Legends for New Multimedia Experiences and NFTs Famed former Marvel Editor-in-ChiefTom DeFalco andartists Ron Frenz and Sal Buscema launch comic books, avatars, and AR enhanced NFT collectibles. Toronto / Vancouver, Canada / Erie PA / New York, NY – April 12, 2021 –Liquid Avatar Technologies Inc. (CSE: LQID / OTC:TRWRF / FRA:4T51) (“Liquid Avatar Technologies” or the “Company”,), a global blockchain, digital-identity and fintech solutions company, together with ImagineAR Inc. (CSE:IP / OTCQB:IPNFF), an Augmented Reality platform company, are excited to announce that Oasis Digital Studios (“Oasis”) has partnered with Apex Comics Group to publish Mr. Right, a new multimedia project by legendary Marvel Entertainment and pop culture veterans Tom DeFalco, Ron Frenz, and Sal Buscema. The program will consist of printed and digital comic books, digital avatars produced for the Liquid Avatar Mobile App and Marketplace, and AR enhanced NFT collectibles with Oasis. A sneak preview of the program will be made virtually on April 13th at the special presentation “NFTs Myths, Market, Media & Mania," hosted by Liquid Avatar, ImagineAR and Oasis Digital Studios: https://hello.liquidavatar.com/oasis-webinar-registration. The integrated campaign, expected to launch in early summer, will feature a series of limited- edition print and digital comic books, along with collector-enhanced NFTs, Liquid Avatar digital icons available in the Liquid Avatar Marketplace, and a fully immersive Augmented Reality multimedia program. A pre-sale waiting list is available for prospective purchasers and NFT collectors at the Oasis website: www.oasisdigitalstudios.com Mr. Right is led by Tom DeFalco, who was Marvel’s 10th Editor-in-Chief. -

Captain Marvel

Roy Thomas’On-The-Marc Comics Fanzine AND $8.95 In the USA No.119 August 2013 A 100th Birthday Tribute to MARC SWAYZE PLUS: SHELDON MOLDOFF OTTO BINDER C.C. BECK JUNE SWAYZE and all the usual SHAZAM! SUSPECTS! 7 0 5 3 6 [Art ©2013 DC7 Comics Inc.] 7 BONUS FEATURE! 2 8 THE MANY COMIC ART 5 6 WORLDS OF 2 TM & © DC Comics. 8 MEL KEEFER 1 Vol. 3, No. 119 / August 2013 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding Cover Artists Marc Swayze Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko Writer/Editorial: Marc Of A Gentleman . 2 With Special Thanks to: The Multi-Talented Mel Keefer . 3 Heidi Amash Aron Laikin Alberto Becattini queries the artist about 40 years in comics, illustration, animation, & film. Terrance Armstard Mark Lewis Mr.Monster’sComicCrypt!TheMenWhoWouldBeKurtzman! 29 Richard J. Arndt Alan Light Mark Arnold Richard Lupoff Michael T. Gilbert showcases the influence of the legendary Harvey K. on other great talents. Paul Bach Giancarlo Malagutti Comic Fandom Archive: Spotlight On Bill Schelly . 35 Bob Bailey Brian K. Morris Alberto Becattini Kevin Patrick Gary Brown throws a 2011 San Diego Comic-Con spotlight on A/E’s associate editor. Judy Swayze Barry Pearl re: [correspondence, comments, & corrections] . 43 Blackman Grey Ray Gary Brown Warren Reece Tributes to Fran Matera, Paul Laikin, & Monty Wedd . -

Friday, October 29Th

fridayprogramming fridayprogramming FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29TH 2 p.m.-2:45 p.m. Jackendoff as he talks with comic kingpin Marv WEBCOMICS: LIGHTING ROUND! Wolfman (Teen Titans), veteran comic writer WRITERS WORKSHOP PRESENTED by Seaside Lobby and editor Barbara Randall Kesel (Watchman, ASPEN Comics Thinking of starting a webcomic, or just curious Hellboy), comic writer Jimmy Palmiotti (Jonah Room 301 as to how the world of webcomics differs Hex), Tom Pinchuk (Hybrid Bastards) and Mickey Join comic book writers J.T. Krul, Scott Lobdell, from print counter-parts? Join these three Neilson (World of Warcraft). David Schwartz, David Wohl, Frank Mastromauro, webcomics pros [Harvey-nominated Dave Kellett and Vince Hernandez as they discuss the ins and (SheldonComics.com /DriveComic.com), Eisner- HOW TO SURVIVE AS AN ARTIST outs of writing stories for comics. Also, learn tips nominated David Malki (Wondermark.com) and WITH Scott Koblish of the trade firsthand from these experienced Bill Barnes (Unshelved.com / NotInventedHere. Room 301 writers as they detail the pitfalls and challenges of com)] as they take you through a 25-minute A panel focusing on the lifelong practical questions breaking into the industry. Also, they will answer guided tour of how to make webcomics work an artist faces. Scott Koblish gives you tips on questions directly in this special intimate workshop as a hobby, part-time job, or full-time career. how to navigate a career that can be fraught with that aspiring writers will not want to miss. Then the action really heats up: 20 minutes of unusual stress. With particular attention paid to fast-paced Q&A, designed to transmit as much thinking about finances in a realistic way, stressing 5 p.m.-7 p.m. -

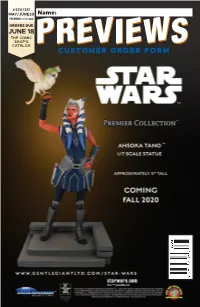

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

Sarah Becan CV

SARAH BECAN 3151 W. WELLINGTON AVE CHICAGO, IL 60618 PH 773.330.9453 WWW.SARAHBECAN.COM SARAH.BECANGMAIL.COM CREATIVE I am a creative director, designer and illustrator located in Chicago. I have twenty years of DIRECTOR professional experience in graphic design, art direction and creative direction, lettering and commercial illustration. I am also a published comics artist, with many titles available at DESIGNER www.sarahbecan.com. I have been twice nominated for Ignatz Awards, and was a recipient ILLUSTRATOR of a Xeric Award and a Stumptown Trophy for my comic art work. PORTFOLIO Recent work can be seen at WWW.SARAHBECAN.COM PROFESSIONAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR, SENIOR DESIGNER, ILLUSTRATOR FOR FATHEAD DESIGN EXPERIENCE Chicago IL. September 2002 - Present Concepting, design and creative direction of client identity packages, websites, print ad campaigns, extensive proposal packages, trade show graphics, product packaging, and email marketing campaigns; drawing and painting for client illustrations. Periodically managing and overseeing small teams of freelance designers and programmers. WWW.FATHEADDESIGN.COM DIGITAL ILLUSTRATOR, PRODUCTION ARTIST FOR ZIPATONI COMPANY St. Louis, MO. June 2000 - August 2002 WWW.ZIPATONI.COM NOW WWW.RIVETGLOBAL.COM GRAPHIC DESIGNER FOR PFEIFFER PLUS COMPANY St. Louis, MO. July 1999 - June 2000 ASSISTANT MANAGER OF ART DEPARTMENT FOR ELAN-POLO SHOES St. Louis, MO. March 1998 - July 1999. EDUCATION B.A. IN STUDIO ART PAINTING AND ILLUSTRATION Beloit College; Beloit, Wisconsin, 1998. B.A. IN MODERN LANGUAGES FRENCH, SPANISH, RUSSIAN Beloit College; Beloit, Wisconsin, 1998. CLIENTS Starr Restaurants Raja Foods INCLUDE Local Foods Saveur Magazine Folk Arts Management Eater.com Levy Restaurants Chicago Reader Bartolotta Restaurants 5th House Ensemble WholeHealth Chicago DePauw University Kelly Restaurant Group Bryn Mawr College Fat Rice TruthOut.com SARAH BECAN 3151 W. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Nov10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 10/13/2010 2:36 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 13NOV 2010 NOV E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG COF FI page:FI 10/14/2010 2:28 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS 1 COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS PHOENIX #0 G ARDDEN ENTERTAINMENT THE BOYS #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SHERLOCK HOLMES: YEAR ONE #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT LOVE FROM THE SHADOWS HC G FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS ARCHIE: 50 TIMES AN AMERICAN ICON SC G THE HERO INITIATIVE BOOK OF LILAH GN G KICKSTART COMICS THE SPIDER #1 G MOONSTONE 1 ROBERT JORDAN‘S NEW SPRING TP G TOR BOOKS VIETNAMERICA GN G VILLARD BOOKS HIGH SCHOOL OF DEAD VOLUME 1 GN G YEN PRESS GRIMM FAIRY TALES: MYTHS AND LEGENDS #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES DC SUPERHERO FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE: BLACKEST NIGHT COLLECTION G COMICS AGATHA HETERODYNE AND THE AIRSHIP CITY: A GIRL GENIUS NOVEL HC G FANTASY/SCI-FI 2 ROBERT E. HOWARD‘S THE SWORD WOMAN AND OTHER HISTORICAL ADVENTURES SC G FANTASY/SCI-FI STAR WARS: KNIGHT ERRANT MMPB G STAR WARS TOYFARE #163 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT TRADING CARDSS 2 UPPER DECK 2010 SP AUTHENTIC FOOTBALL TRADING CARDS G THE UPPER DECK COMPANY STAR WARS GALAXY SERIES 6 TRADING CARDS G TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL MARVEL VS. CAPCOM: DAVID VS GOLIATH T-SHIRT G MAD ENGINE BRIGHTEST DAY: THE FLASH WHITE T-SHIRT G GRAPHITTI DESIGNS LEGION II SYMBOL BLACK T-SHIRT G GRAPHITTI DESIGNS TOKIDOKI X MARVEL: METAL THOR BLACK T-SHIRT G TOKIDOKI TOYS & STATUES 3 WORLD‘S GREATEST DC HEROES RETRO ACTION FIGURES G DC HEROES 3 DOCTOR WHO: MATT SMITH AS THE ELEVENTH DOCTOR MAXI-BUST G DOCTOR WHO -

Parking Information

Parking Information Suburban Collection Showplace is conveniently located at 46100 Grand River Avenue, between Novi and Beck Roads in Novi, MI. Our Facility can be accessed From I-96 at the Novi and Beck Road exits. Parking will have a small charge For each day oF the event. There will be a Fully-equipped press room on site. Interviews may not be conducted inside the press room. More details on the location oF the press room will be provided. 3 Motor City Comic Con Floor Plan 2014 4 Schedule of Events *Schedule is subject to change Friday: ñ “Sweep the Leg” Panel with Billy Zabka and Martin Kove-Time TBD o They will discuss their roles in The Karate Kid ñ Ready-To-Play Deck Event-Beginners Level-Time TBD o Card game For beginners ñ Friday Anime Programming Schedule: o 11:30 a.m: Urusei Yatsura o Noon: Dirty Pair o 12:55 p.m.: Bodacious Space Pirates o 2:10 p.m.: Shinesmen o 3:10 p.m.: Saint Seiya o 4:30 p.m.: Tiger & Bunny- The Movie o 6:00 p.m.: Read or Die Saturday: ñ Costume Cosplay Contest (ages 13+)-Time TBD ñ Standard Format Constructed Event-Experienced Level o Card game For experienced gamers ñ Saturday Anime Programming Schedule: o 10:30 a.m.: Little Witch Academia o 11:00 a.m.: Fairy Tail o 12:15 p.m.: TBA o 2:15 p.m.: Nadia: The Secret oF Blue Water o 3:30 p.m.: TBA o 4:45 p.m.: Level E o 5:30 p.m.: TBA o 6:15 p.m.: Good Luck Girl o 7:30 p.m.: Akira o 9:30 p.m.: High School oF the Dead o 10:30 p.m.: Space Adventure Cobra ñ Get Drunk on Comics Panel-Time TBD o The guys From the Drunk on Comics podcast will discuss podcasting,