Protection of Schools During Armed Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/75/6 (Sect. 1) General Assembly

United Nations A/75/6 (Sect. 1) General Assembly Distr.: General 27 April 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 141 of the preliminary list* Proposed programme budget for 2021 Proposed programme budget for 2021 Part I Overall policymaking, direction and coordination Section 1 Overall policymaking, direction and coordination Contents Page I. Policymaking organs ............................................................ 5 1. General Assembly .......................................................... 8 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2021*** ................ 8 2. Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (including its secretariat) ................................................................ 12 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2021*** ................ 12 3. Committee on Contributions ................................................. 16 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2021*** ................ 16 4. Board of Auditors (including its secretariat) ..................................... 17 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2021*** ................ 17 5. United Nations Joint Staff Pension Board (including United Nations participation in the costs of the secretariat of the United Nations Joint Staff Pension Fund) .............. 21 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2021*** ................ 21 * A/75/50. ** In The part consisting of the proposed programme plan for 2021 is submitted for consideration -

Download the Full Report

H U M A N PROTECTING SCHOOLS FROM R I G H T S MILITARY USE WATCH Laws, Policies, and Military Doctrine Protecting Schools from Military Use Law, Policy, and Military Doctrine Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34525 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org March 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34525 Protecting Schools from Military Use Law, Policy, and Military Doctrine Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 6 I. International .................................................................................................................. -

1 BACKGROUND PAPER1 on ATTACKS AGAINST GIRLS SEEKING to ACCESS EDUCATION Table of Contents INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND PAPER1 ON ATTACKS AGAINST GIRLS SEEKING TO ACCESS EDUCATION Table of Contents INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 2 I. FRAMING THE PROBLEM .................................................................................. 4 II. THE APPLICABLE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORKS ON EDUCATION ......................................................................... 6 A. THE FOUR ‘AS’ FRAMEWORK ............................................................................... 8 B. RIGHTS THROUGH EDUCATION ............................................................................. 9 III. ATTACKS ON GIRLS’ EDUCATION IN SITUATIONS OF INSECURITY AND CRISIS............................................................................................................... 10 IV. CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF ATTACKS ON GIRLS’ EDUCATION ............................................................................................................. 14 A. CAUSES OF ATTACKS AGAINST GIRLS’ EDUCATION ............................................... 14 B. HUMAN RIGHTS CONSEQUENCES OF ATTACKS ON GIRLS’ EDUCATION ................... 17 V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................. 22 VI. RESOURCES ....................................................................................................... 28 1 This background paper will be presented to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination of against Women, to contribute to the -

Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women Review of Niger 81St Pre-Session June 2021

Human Rights Watch Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Review of Niger 81st Pre-Session June 2021 We write in advance of the 81st pre-session of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and its adoption of a list of issues prior to reporting regarding Niger’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. This submission includes information on barriers to the right to primary and secondary education in Niger and the country’s efforts to protect education from attack during armed conflict. Barriers to the Right to Primary and Secondary Education (Article 10 and 16) Pregnant Pupils Niger has one of the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy, according to UNICEF data analyzed by Human Rights Watch.1 In Niger, 180 per 1000 women ages 15-19 gave birth.2 Only 42 percent of girls are enrolled in basic education, compared with 58 percent of boys, according to the Nigerien government.3 Many girls’ education suffers as a result of early marriage and pregnancy.4 Niger is among 24 countries that lack a policy or law to protect pregnant girls’ right to education, based on research by Human Rights Watch on pregnant pupils’ and adolescent parents’ rights to primary and secondary education in all African Union member countries.5 1 UNICEF, “Unicef Data Warehouse,” June 9, 2021, https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=UNICEF_SSA+KEN+ COD+CAF+NGA+NER+MOZ+ZAF+CMR+MWI+UGA+TZA.MNCH_BIRTH18..&startPeriod=2009&endPeriod=2021 (accessed June 9, 2021). -

Impact of COVID-19 on Children's Education in Africa Submission

Impact of Covid-19 on Children’s Education in Africa Submission to The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child 35th Ordinary Session 31 August – 4 September 2020 Human Rights Watch Observer status N⁰. 025/2017 Human Rights Watch respectfully submits this written presentation to contribute testimony from children to the discussion on the impact of Covid-19 on children at the 35th Ordinary Session of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Between April and August 2020, Human Rights Watch conducted 57 remote interviews with students, parents, teachers, and education officials across Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia to learn about the effects of the pandemic on children’s education. Our research shows that school closures caused by the pandemic exacerbated previously existing inequalities, and that children who were already most at risk of being excluded from a quality education have been most affected. Children Receiving No Education Many children received no education after schools closed across the continent in March 2020.1 “My child is no longer learning, she is only waiting for the reopening to continue with her studies,” said a mother of a 9-year-old girl in eastern Congo.2 A mother of two preschool-aged children in North Kivu, Congo, said, “It does not make me happy that my children are no longer going to school. Years don’t wait for them. They have already lost a lot... What will become -

General Assembly Distr.: Limited 6 July 2021

United Nations A/HRC/47/L.4 General Assembly Distr.: Limited 6 July 2021 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-seventh session 21 June–13 July 2021 Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Albania,* Armenia, Australia,* Austria, Belgium,* Bosnia and Herzegovina,* Bulgaria, Canada,* Chile,* Croatia,* Cyprus,* Czechia, Ecuador,* Estonia,* Fiji, Finland,* France, Georgia,* Germany, Greece,* Hungary,* Ireland,* Italy, Latvia,* Lithuania,* Luxembourg,* Malta,* Mexico, Monaco,* Montenegro,* Morocco,* Nepal, Netherlands, North Macedonia,* Paraguay,* Peru,* Philippines, Portugal,* Qatar,* Romania,* Serbia,* Slovakia,* Slovenia,* Spain,* Sweden,* Switzerland,* Ukraine, United States of America* and Uruguay: draft resolution 47/… The right to education The Human Rights Council, Guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, Reaffirming the human right of everyone to education, which is enshrined in, inter alia, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the -

When in Conflict: Guaranteeing the Right to Education in India

Human Rights Brief Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 6 2020 When in Conflict: Guaranteeing the Right to Education in India Sanskriti Sanghi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Sanghi, Sanskriti (2020) "When in Conflict: Guaranteeing the Right to Education in India," Human Rights Brief: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief/vol23/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRACTITIONERSanghi: Right to Education ARTICLES in India When in Conflict: Guaranteeing the Right to Education in India by Sanskriti Sanghi* INTRODUCTION toms applicable in armed conflict. This is established in Article 52(2) of the Additional Protocol I to the Since 2007, the military use of educational institutions Geneva Conventions, which recognized that “attacks has been documented in 29 countries, commonly shall be limited strictly to military objectives,”[5] and those countries which have been experiencing armed must comply with the rule of distinction and propor- conflict during the past decade.[1] Educational insti- tionality as required in an attack upon an object.[6] tutions have been taken over, partially or in entirety, Additionally, international humanitarian law states in order to be converted into military bases, used for that “intentionally directed attacks against buildings training fighters, used as interrogation and detention dedicated to education” constitute war crimes.[7] facilities, or to hide weapons. -

Pdf | 427.52 Kb

Violence Against or Obstruction of Education in Myanmar February-May 2021 July 2021 Mass Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) protests have been taking place across Myanmar after the Myanmar armed forces (known as the Tatmadaw) seized control of the country on 1 February following a general election that the National League for Democracy (NLD) party won by a landslide and formed the State Administration Council (SAC) on 2 February. The military have since declared a state of emergency that will last for at least a year. A number of countries have condemned the takeover and subsequent violent crackdown on protesters. Hundreds of people, including children, have been killed and many injured during the protests. Over the past months violence by both state security forces and non-state armed groups has distinctly impacted teachers, schools and universities. Support for the opposition has traditionally been high among university and secondary school students and some of their teachers. This has drawn educational institutions into the conflict affecting many students including even those that may not be opposition supporters. This document by Insecurity Insight highlights reported incidents affecting teachers, schools and universities in Myanmar between 01 February and 31 May 2021 to illustrate the impact of the conflict on education. Threats and violence against education facilities and teachers affects the provision of education directly when education facilities are no safe places and teachers disappear or are fearful. Students participating in anti-junta protests have been equally touched by crack-down on the opposition. However, they are not the specific focus of this report. Incident monitoring is not well suited to identify students affected by conflict. -

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief January 2020 UNICEF January 2020 Central Sahel Advocacy Brief A Children under attack The surge in armed violence across Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is having a devastating impact on children’s survival, education, protection and development. The Sahel, a region of immense potential, has long been one of the most vulnerable regions in Africa, home to some countries with the lowest development indicators globally. © UNICEF/Juan Haro Cover image: © UNICEF/Vincent Tremeau The sharp increase in armed attacks on communities, schools, health centers and other public institutions and infrastructures is at unprecedented levels. Violence is disrupting livelihoods and access to social services including education and health care. Insecurity is worsening chronic vulnerabilities including high levels of malnutrition, poor access to clean water and sanitation facilities. As of November 2019, 1.2 million people are displaced, of whom more than half are children.1 This represents a two-fold increase in people displaced by insecurity and armed conflict in the Central Sahel countries in the past 12 months, and a five-fold increase in Burkina Faso alone.* Reaching those in need is increasingly challenging. During the past year, the rise in insecurity, violence and military operations has hindered access by humanitarian actors to conflict-affected populations. The United Nations Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS) continues to spur inter-agency cooperation. UNISS serves as the regional platform to galvanize multi-country and cross-border efforts to link development, humanitarian and peace programming (triple nexus). Partners are invited to engage with the UNISS platform to scale-up action for resilience, governance and security. -

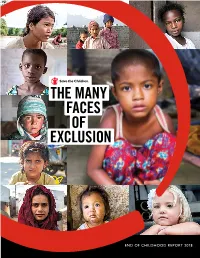

The Many Faces of Exclusion: 2018 End of Childhood Report

THE MANY FACES OF EXCLUSION END OF CHILDHOOD REPORT 2018 Six-year-old Arwa* and her family were displaced from their home by armed conflict in Iraq. CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 End of Childhood Index Results 2017 vs. 2018 7 THREAT #1: Poverty 15 THREAT #2: Armed Conflict 21 THREAT #3: Discrimination Against Girls 27 Recommendations 31 End of Childhood Index Rankings 32 Complete End of Childhood Index 2018 36 Methodology and Research Notes 41 Endnotes 45 Acknowledgements * after a name indicates the name has been changed to protect identity. Published by Save the Children 501 Kings Highway East, Suite 400 Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 United States (800) 728-3843 www.SavetheChildren.org © Save the Children Federation, Inc. ISBN: 1-888393-34-3 Photo:## SAVE CJ ClarkeTHE CHILDREN / Save the Children INTRODUCTION The Many Faces of Exclusion Poverty, conflict and discrimination against girls are putting more than 1.2 billion children – over half of children worldwide – at risk for an early end to their childhood. Many of these at-risk children live in countries facing two or three of these grave threats at the same time. In fact, 153 million children are at extreme risk of missing out on childhood because they live in countries characterized by all three threats.1 In commemoration of International Children’s Day, Save the Children releases its second annual End of Childhood Index, taking a hard look at the events that rob children of their childhoods and prevent them from reaching their full potential. WHO ARE THE 1.2 BILLION Compared to last year, the index finds the overall situation CHILDREN AT RISK? for children appears more favorable in 95 of 175 countries. -

Strengthening Resilience

International Review of the Red Cross (2017), 99 (2), 797–820. The missing doi:10.1017/S1816383118000553 Strengthening resilience: The ICRC’s community-based approach to ensuring the protection of education Geoff Loane and Ricardo Fal-Dutra Santos Geoff Loane is currently Head of Education at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). He has spent more than thirty years in a variety of operational positions in the field and at ICRC headquarters. Ricardo Fal-Dutra Santos is a Protection Delegate in the Pretoria Regional Delegation. He was formerly an Associate in the Protection of the Civilian Population Unit of the ICRC, where he worked on child protection issues, including children’s access to education. Abstract Education has received increased attention within the humanitarian sector. In conflict-affected contexts, access to education may be hampered by attacks against and the military use of educational facilities as well as attacks and threats of attacks against students, teachers and other education-related persons. Affected populations may also find themselves unable to access education, for example due to displacement. This article looks into the different sets of humanitarian responses aimed at (1) ensuring the protection of educational facilities and related persons, mostly through advocacy efforts centred on weapons bearers, and (2) (re-)establishing education services where they are not present or are no longer functioning, mostly through programmes directed at affected populations. It then argues that, in contrast with © icrc 2018 797 G. Loane and R. Fal-Dutra Santos dominant practices, the protection of education can also be ensured through programmatic responses with meaningful participation of affected communities, and examines the example of the Safer Schools programme in Ukraine. -

Childrenand Armedconflict

MONTHLY UPDATE: Children and Armed Conflict SEPTEMBER 2017 Recommendations to the Security Council AFGHANISTAN The Afghan National Police (ANP), including the Afghan Local Police (ALP), and three armed groups (Haqqani Situations before the Network, Hezb-i-Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and Taliban forces) are listed for recruitment and use of Council involving parties children. All three armed groups are also listed for killing and maiming, while the Taliban is further listed for listed for grave violations attacks on schools and/or hospitals and abduction. In September, the Secretary-General (SG) will report on against children: UNAMA’s progress pursuant to SCR 2344 (2017). From the last progress report (A/71/932/S/2017/508, para. Afghanistan 26), as of April 10, 135 children were detained on national security-related charges, including for association with anti-Government armed groups, and held in an adult maximum security detention facility in Parwan Central African Republic Province. Council Members should: Colombia Urge the Government to remove Article Nine of Annex One of the Criminal Procedural Code, which Democratic Republic enables the transfer of children to the maximum security detention facility in Parwan and apply of the Congo fully and without delay Afghanistan’s national Juvenile Code and the National Directorate for Iraq Security directive issued on July 2, 2016, instructing that children no longer be held in its detention facilities and the cessation of transfers of children to the prison; children currently being held Mali should immediately be transferred to juvenile rehabilitation centers in the provinces of origin; Myanmar (Burma) Echoing the SG’s calls (A/71/932/S/2017/508, para.