Relative Abuse Liability of GHB in Humans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PENTOBARBITAL SODIUM- Pentobarbital Sodium Injection Akorn, Inc

PENTOBARBITAL SODIUM- pentobarbital sodium injection Akorn, Inc. ---------- Nembutal® Sodium Solution CII (pentobarbital sodium injection, USP) + novaplus TM Rx only Vials DO NOT USE IF MATERIAL HAS PRECIPITATED DESCRIPTION The barbiturates are nonselective central nervous system depressants which are primarily used as sedative hypnotics and also anticonvulsants in subhypnotic doses. The barbiturates and their sodium salts are subject to control under the Federal Controlled Substances Act (See “Drug Abuse and Dependence” section). The sodium salts of amobarbital, pentobarbital, phenobarbital, and secobarbital are available as sterile parenteral solutions. Barbiturates are substituted pyrimidine derivatives in which the basic structure common to these drugs is barbituric acid, a substance which has no central nervous system (CNS) activity. CNS activity is obtained by substituting alkyl, alkenyl, or aryl groups on the pyrimidine ring. NEMBUTAL Sodium Solution (pentobarbital sodium injection) is a sterile solution for intravenous or intramuscular injection. Each mL contains pentobarbital sodium 50 mg, in a vehicle of propylene glycol, 40%, alcohol, 10% and water for injection, to volume. The pH is adjusted to approximately 9.5 with hydrochloric acid and/or sodium hydroxide. NEMBUTAL Sodium is a short-acting barbiturate, chemically designated as sodium 5-ethyl-5-(1- methylbutyl) barbiturate. The structural formula for pentobarbital sodium is: The sodium salt occurs as a white, slightly bitter powder which is freely soluble in water and alcohol but practically insoluble in benzene and ether. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Barbiturates are capable of producing all levels of CNS mood alteration from excitation to mild sedation, to hypnosis, and deep coma. Overdosage can produce death. In high enough therapeutic doses, barbiturates induce anesthesia. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

List of Union Reference Dates A

Active substance name (INN) EU DLP BfArM / BAH DLP yearly PSUR 6-month-PSUR yearly PSUR bis DLP (List of Union PSUR Submission Reference Dates and Frequency (List of Union Frequency of Reference Dates and submission of Periodic Frequency of submission of Safety Update Reports, Periodic Safety Update 30 Nov. 2012) Reports, 30 Nov. -

211230Orig1s000 211230Orig2s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 211230Orig1s000 211230Orig2s000 RISK ASSESSMENT and RISK MITIGATION REVIEW(S) Division of Risk Management (DRISK) Office of Medication Error Prevention and Risk Management (OMEPRM) Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Application Type NDA Application Number 211230 PDUFA Goal Date December 20, 2018 OSE RCM # 2018‐1313 Reviewer Name(s) Naomi Redd, Pharm.D. Team Leader Elizabeth Everhart, RN, MSN, ACNP Division Director Cynthia LaCivita, Pharm.D. Review Completion Date September 25, 2018 Subject Evaluation of the Need for a REMS Established Name Solriamfetol Trade Name Sunosi Name of Applicant Jazz Pharmaceuticals Therapeutic class Dopamine and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (DNRI) Formulation 75 mg, 150 mg (b) (4) oral tablets Dosing Regimen Take one tablet once daily upon awakening 1 Reference ID: 4327439 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Product Information .......................................................................................................................................... -

Deliberate Self-Poisoning with a Lethal Dose of Pentobarbital: Survival with Supportive Care

Deliberate self-poisoning with a lethal dose of pentobarbital: Survival with supportive care. (1) (1,2) Santosh Gone , Andis Graudins (1) Clinical Toxicology Service, Program of Emergency Medicine, Monash Health (2) Monash Emergency Research Collaboration, Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, Monash University Abstract 84 INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT (continued) DISCUSSION Pentobarbital (Nembutal) is short acting In the ED: Pentobarbital has been a banned substance for barbiturate sedative-hypnotic, currently widely GCS: 3/15, fixed dilated pupils, apnoeic and human use in Australia since 1998. However, it can used in veterinary practice for anesthesia and ventilated. be procured overseas or bought on the internet. euthanasia. Pulse: 116 bpm sinus tachycardia BP: 115/60 on epinephrine infusion. Pentobarbital is recommended as an effective It is also commonly recommended as a VBG: pH 7.03 pCO2 77 mmHg Bicarb 19 mmol/L agent for use in euthanasia due to its apparently euthanasia drug for assisted suicide and it is Lactate 8.8 mmol/L peaceful transition to death. unlikely that any resuscitative measures will be Activated charcoal (50g) given via an NG tube. attempted in such cases. Course in the Intensive Care Department: In a case series of 150 assisted suicides in Day-1 post-OD: Sweden, a 100% success rate was seen with Intentional overdose results in depression of - Absent brain stem reflexes and fixed dilated pupils for ingestion of 9 grams. Cardiovascular collapse was brain stem function and rapid onset respiratory five days. seen within 15 minutes in 30% of patients. It is rare depression and apnoea. Hypotension also - Diabetes insipidus developed with urine output of to see survival after intentional ingestion for develops, followed by cardiovascular collapse 300ml/hour. -

Pentobarbital Sodium

PENTobarbital Sodium Brand names Nembutal Sodium Medication error Look-alike, sound-alike drug names. Tall man letters (not FDA approved) are recommended potential to decrease confusion between PENTobarbital and PHENobarbital.(1,2) ISMP recommends the following tall man letters (not FDA approved): PENTobarbital.(30) Contraindications Contraindications: In patients with known hypersensitivity to barbiturates or any com- and warnings ponent of the formulation.(2) If an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction or a life-threatening adverse event occurs, rapid substitution of an alternative agent may be necessary. If pentobarbital is discontinued due to development of a rash, an anticonvulsant that is structurally dissimilar should be used (i.e., nonaromatic). (See Rare Adverse Effects in the Comments section.) Also contraindicated in patients with a history of manifest or latent porphyria.(2) Warnings: Rapid administration may cause respiratory depression, apnea, laryngospasm, or vasodilation with hypotension.(2) Should be withdrawn gradually if large doses have been used for prolonged periods.(2) Paradoxical excitement may occur or important symptoms could be masked when given to patients with acute or chronic pain.(2) May be habit forming. Infusion-related Respiratory depression and arrest requiring mechanical ventilation may occur. Monitor cautions oxygen saturation. If hypotension occurs, the infusion rate should be decreased and/or the patient should be treated with IV fluids and/or vasopressors. Pentobarbital is an alkaline solution (pH = 9–10.5); therefore, extravasation may cause tissue necrosis.(2) (See Appendix E for management.) Gangrene may occur following inadvertent intra-arterial injection.(2) Dosage Medically induced coma (for persistently elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) or refractory status epilepticus): Patient should be intubated and mechanically ventilated. -

And Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium and Sodium Oxybates (Xywav™)

Louisiana Medicaid Sodium Oxybate (Xyrem®) and Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium and Sodium Oxybates (Xywav™) The Louisiana Uniform Prescription Drug Prior Authorization Form should be utilized to request clinical authorization for sodium oxybate (Xyrem®) and calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium oxybates (Xywav™). These agents have Black Box Warnings and are subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) under FDA safety regulations. Please refer to individual prescribing information for details. Approval Criteria • The recipient is 7 years of age or older on date of request; AND • The recipient has a documented diagnosis of narcolepsy or cataplexy; AND • The prescribing provider is a Board-Certified Neurologist or a Board-Certified Sleep Medicine Physician; AND • By submitting the authorization request, the prescriber attests to the following: o The prescribing information for the requested medication has been thoroughly reviewed, including any Black Box Warning, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), contraindications, minimum age requirements, recommended dosing, and prior treatment requirements; AND o All laboratory testing and clinical monitoring recommended in the product prescribing information have been completed as of the date of the request and will be repeated as recommended; AND o The recipient has no inappropriate concomitant drug therapies or disease states. Duration of initial authorization approval: 3 months Reauthorization Criteria • The recipient continues to meet all initial approval criteria; AND -

Misuse of Drugs Act 1975

Reprint as at 1 July 2014 Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 Public Act 1975 No 116 Date of assent 10 October 1975 Commencement see section 1(2) Contents Page Title 4 1 Short Title and commencement 4 2 Interpretation 4 3 Act to bind the Crown 9 3A Classification of drugs 9 4 Amendment of schedules that identify controlled drugs 10 and precursor substances, and set amount, level, or quantity at and over which controlled drugs are presumed to be for supply 4A Procedure for bringing Order in Council made under 12 section 4(1) or (1B) into force 4B Matters to which Minister must have regard before 13 recommending Order in Council under section 4(1) or (1B) 4C Temporary class drug notice [Repealed] 14 4D Effect of temporary class drug notice [Repealed] 15 4E Duration of temporary class drug notice [Repealed] 15 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this official reprint. Note 4 at the end of this reprint provides a list of the amendments incorporated. This Act is administered by the Ministry of Health. 1 Reprinted as at Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 1 July 2014 5 Advisory and technical committees 15 5AA Expert Advisory Committee on Drugs 15 5A Approved laboratories 17 5B Functions of Minister 17 6 Dealing with controlled drugs 18 7 Possession and use of controlled drugs 20 8 Exemptions from sections 6 and 7 22 9 Cultivation of prohibited plants 26 10 Aiding offences against corresponding law of another 27 country 11 Theft, etc, of controlled drugs 28 12 Use of premises or vehicle, etc 29 12A Equipment, -

Prescription Drug Management

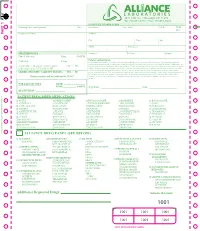

Check out our new site: www.acllaboratories.com Prescription Drug Management Non Adherence, Drug Misuse, Increased Healthcare Costs Reports from the Centers for DiseasePrescription Control and Prevention (CDC) say Drug deaths from Managementmedication overdose have risen for 11 straight years. In 2008 more than 36,000 people died from drug overdoses, and most of these deaths were caused by prescription Nondrugs. Adherence,1 Drug Misuse, Increased Healthcare Costs The CDC analysis found that nearly 40,000 drug overdose deaths were reported in 2010. Prescribed medication accounted for almost 60 percent of the fatalities—far more than deaths from illegal street drugs. Abuse of painkillers like ReportsOxyContin from and the VicodinCenters forwere Disease linked Control to the and majority Prevention of the (CDC) deaths, say deaths from according to the report.1 medication overdose have risen for 11 straight years. In 2008 more than 36,000 people died from drug overdoses, and most of these deaths were caused by prescription drugs. 1 A health economics study analyzed managed care claims of more than 18 million patients, finding that patients undergoing opioid therapyThe CDCfor chronic analysis pain found who that may nearly not 40,000 be following drug overdose their prescription deaths were regimenreported in 2010. Prescribed medication accounted for almost 60 percent of the fatalities—far more than deaths have significantly higher overall healthcare costs. from illegal street drugs. Abuse of painkillers like OxyContin and Vicodin were linked to the majority of the deaths, according to the report.1 ACL offers drug management testing to provide information that can aid clinicians in therapy and monitoring to help improve patientA health outcomes. -

Nonpeptide Orexin Type-2 Receptor Agonist Ameliorates Narcolepsy-Cataplexy Symptoms in Mouse Models

Nonpeptide orexin type-2 receptor agonist ameliorates narcolepsy-cataplexy symptoms in mouse models Yoko Irukayama-Tomobea,1, Yasuhiro Ogawaa,1, Hiromu Tominagaa,1, Yukiko Ishikawaa, Naoto Hosokawaa, Shinobu Ambaia, Yuki Kawabea, Shuntaro Uchidaa, Ryo Nakajimaa, Tsuyoshi Saitoha, Takeshi Kandaa, Kaspar Vogta, Takeshi Sakuraia, Hiroshi Nagasea, and Masashi Yanagisawaa,2 aInternational Institute for Integrative Sleep Medicine, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8575, Japan Contributed by Masashi Yanagisawa, March 22, 2017 (sent for review January 13, 2017; reviewed by Thomas S. Kilduff and Thomas E. Scammell) Narcolepsy-cataplexy is a debilitating disorder of sleep/wakefulness methylphenidate and modafinil), sedative (sodium oxybate), and caused by a loss of orexin-producing neurons in the lateroposterior tricyclic antidepressants. However, the use of these medications is hypothalamus. Genetic or pharmacologic orexin replacement ame- often limited by adverse side effects such as headache, nausea, liorates symptoms in mouse models of narcolepsy-cataplexy. We anxiety, irritability, and insomnia. have recently discovered a potent, nonpeptide OX2R-selective Murine models of narcolepsy-cataplexy include OXKO mice − − − − agonist, YNT-185. This study validates the pharmacological activity (2), orexin receptor-deficient (Hcrtr1 / ;Hcrtr2 / , abbreviated as of this compound in OX2R-transfected cells and in OX2R-expressing OXRDKO) mice, and the orexin/ataxin-3 transgenic mice (in neurons in brain slice preparations. Intraperitoneal, and intracere- which orexin neurons are genetically and postnatally ablated) broventricular, administration of YNT-185 suppressed cataplexy-like (12). Tabuchi et al. created another narcolepsy mouse model, episodes in orexin knockout and orexin neuron-ablated mice, but not which expressed diphtheria toxin A in orexin neurons under in orexin receptor-deficient mice. -

Additional Requested Drugs

PART 1 PART PATIENT PRESCRIBED MEDICATIONS: o ACTIQ o DESIPRAMINE o HYDROCODONE o MORPHINE o ROXICODONE o ADDERALL o DIAZEPAM* o HYDROMORPHONE o MS CONTIN o SOMA o ALPRAZOLAM* o DILAUDID o IMIPRAMINE o NEURONTIN o SUBOXONE o AMBIEN o DURAGESIC o KADIAN o NORCO o TEMAZEPAM o AMITRIPTYLINE o ELAVIL o KETAMINE o NORTRIPTYLINE o TRAMADOL* o ATIVAN o EMBEDA o KLONOPIN o NUCYNTA o TYLENOL #3 o AVINZA o ENDOCET o LORAZEPAM o OPANA o ULTRAM o BUPRENEX o FENTANYL* o LORTAB o OXYCODONE o VALIUM o BUPRENORPHINE o FIORICET o LORCET o OXYCONTIN o VICODIN o BUTRANS o GABAPENTIN o LYRICA o PERCOCET o XANAX o CLONAZEPAM* o GRALISE o METHADONE o RESTORIL TO RE-ORDER CALL RITE-PRINT 718/384-4288 RITE-PRINT CALL TO RE-ORDER ALLIANCE DRUG PANEL (SEE BELOW) o ALCOHOL o BARBITURATES o ILLICITS o MUSCLE RELAXANTS o OPIODS (SYN) ETHANOL PHENOBARBITAL 6-MAM (HEROIN)* CARISPRODOL FENTANYL* BUTABARBITAL a-PVP MEPROBAMATE MEPERIDINE o AMPHETAMINES SECOBARBITAL BENZOYLECGONINE NALOXONE AMPHETAMINE PENTOBARBITAL LSD o OPIODS (NATURAL) METHADONE* METHAMPHETAMINE BUTALBITAL MDA CODEINE METHYLPHENEDATE MDEA MORPHINE o NON-OPIOID o BENZODIAZEPINES MDMA ANALGESICS o OPIODS (SEMI-SYN) o ANTICONVULSIVES ALPRAZOLAM* MDPV TRAMADOL BUPRENORPHINE* GABAPENTIN CLONAZEPAM* MEPHEDRONE TAPENTADOL DIHROCODEINE PREGABALIN DIAZEPAM METHCATHINONE DESOMORPHINE o NON-BENZODIAZEPINE FLUNITRAZEPAM* METHYLONE HYDROCODONE HYPNOTIC o ANTIDEPRESSANTS FLURAZEPAM* PCP HYDROMORPHONE ZOLPIDEM* AMITRIPTYLINE LORAZEPAM THC* OXYCODONE DOXEPIN OXAZEPAM CBD ° OXYMORPHONE o MISCELLANEOUS DRUGS IMIPRIMINE -

The Use of Barbital Compounds in Producing Analgesia and Amnesia in Labor

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1939 The Use of barbital compounds in producing analgesia and amnesia in labor Stuart K. Bush University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Bush, Stuart K., "The Use of barbital compounds in producing analgesia and amnesia in labor" (1939). MD Theses. 730. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/730 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF THE BARBITAL COMPOUl~DS IN PRODUCING ANALGESIA AND .AMNESIA.IN LABOR Stuart K. Bush Senior Thesis Presented to the College of Medicine, University of Nebraska, Omaha, 1939 481021 THE USE OF THE BARBITAL COMPOUNDS IN PROLUCING ANALGESIA AND AMNESIA IN LABOR The Lord God said unto Eve, "I will greatly mul tiply thy sorrow and thJ conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children." Genesis 3:lti Many a God-fearing man has held this to mean that any attempt to ease the suffering of the child bearing mother would be a direct violation of the Lord's decree. Even though the interpretation of this phrase has formed a great barrier to the advance ment of the practice of relieving labor pains, attempts to achieve this beneficent goal have been made at va rious times throughout the ages.