Green Naughty Bits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011 Table of Contents: Fact Sheet 3 Why I Chose Top Shelf 4 Interview with Chris Staros 5 Book Review: Blankets by Craig Thompson 12 2 Fact Sheet: Top Shelf Productions Web Address: www.topshelfcomix.com Founded: 1997 Founders: Brett Warnock & Chris Staros Editorial Office Production Office Chris Staros, Publisher Brett Warnock, Publisher Top Shelf Productions Top Shelf Productions PO Box 1282 PO Box 15125 Marietta GA 30061-1282 Portland OR 97293-5125 USA USA Distributed by: Diamond Book Distributors 1966 Greenspring Dr Ste 300 Timonium MD 21093 USA History: Top Shelf Productions was created in 1997 when friends Chris Staros and Brett Warnock decided to become publishing partners. Warnock had begun publishing an anthology titled Top Shelf in 1995. Staros had been working with cartoonists and had written an annual resource guide The Staros Report regarding the best comics in the industry. The two joined forces and shared a similar vision to advance comics and the graphic novel industry by promoting stories with powerful content meant to leave a lasting impression. Focus: Top Shelf publishes contemporary graphic novels and comics with compelling stories of literary quality from both emerging talent and known creators. They publish all-ages material including genre fiction, autobiographical and erotica. Recently they have launched two apps and begun to spread their production to digital copies as well. Activity: Around 15 to 20 books per year, around 40 titles including reprints. Submissions: Submissions can be sent via a URL link, or Xeroxed copies, sent with enough postage to be returned. -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

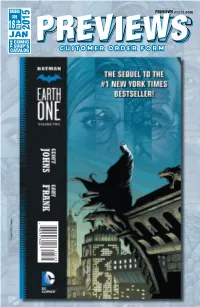

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Exhibitor List July 7, 2009

American Library Association Annual Conference Exhibitor List as of July 7, 2009 Company Name Booth Number(s) 3M Library Systems 2416 A+ Child Supply Inc. 1448 A1Books.com/A1Overstock.com 938 AAAS/Science Online 3953 Abbeville Press, Inc. 1820 ABC-CLIO 3918 ABDO Publishing - Spotlight - Magic Wagon - ABDO iBooks 1951 Abingdon Press 3152 Able Card, LLC 4451 Abrams/Amulet/STC. 2343 Access Control Solutions & Selectec, Inc. 1213 Accessible Archives 4918 AccuCut 1526 Acorn Media 2131 Action! Library Media Service 4138 Adam Matthew Digital 5336 Advance Publishing 1649 Agati, Inc. 4619 ALA Guide to Reference. 1426 ALA Membership Pavilion 3034 ALA Public Programs Office 3254 ALA Publishing 1426 ALA/ Affiliate Members 3429 ALA/AFL-CIO/RUSA Joint Com. 3227 Albert Whitman & Company 2123 Alexander Street Press 1852, 3223 Alexandria 3554 Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill (A division of Workman Publishing Company) 1416 Alibris 3111 Alliance Entertainment 3940 Altarama Information Systems 1138 Alternative Press Center 1637 Ambassador Books and Media 4626 Ambrose Video Publishing 4237 America Reads Spanish 2229 American City Business Journals 4739 American Collective Stand 2029 American Interfile & Library Relocations 1242 American Psychological Association 5034 American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 3217 Annick Press 2359 Ariel Arwen Jewelry Designs 1047 Arte Publico Press 3654 Artisan Books (A division of Workman Publishing Company) 1416 Atiz Innovation, Inc. 922 Atlas & Co. 1616 Atlas Systems 4416 Auburn Moon Agency 3653 Audio Editions Books On Cassette & CD 1936 August House Publishers 2451 Auto-Graphics, Inc. 2651 Aux Amateurs De Livres 4529 AWE, Inc. 5042 Azuradisc, Inc. 5327 B-books, Ltd. / Kiki Magazine 2660 Backstage Library Works 4430 Baker & Taylor 3620 Barnes & Noble Booksellers 4351 Basch Subscriptions 3518 BayScan Technologies, LLC 934 BBC Audiobooks America 4934 BCI/Eurobib c/o Longo Inc. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Autobiographical Comics Graphic Novels

✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧ ✵National Book-Collecting Contest✵ ❧ The Complexities of Ordinary Life: Autobiographical Comics AND Graphic Novels ❝ ❝Collect ‘em all! ❞ Trade ‘em with your friends!❞ COLLECTED AND DESCRIBED BY: ✻ Naseem Hrab ✻ ✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧✧ The Complexities of Ordinary Life: Autobiographical Comics and Graphic Novels Being raised by two psychiatrists has made me extraordinarily interested in learning about the lives of others. While autobiographical comics may seem like an odd crib sheet to use to learn about the human condition, their confessional style provides readers like me with the answers to the questions we dare not ask. I equate reading an autobiographical comic with the occurrence of a stranger handing you his diary, staring meaningfully into your eyes and saying, “I want you to read this… all of it. Oh, and just so you know, I drew pictures of everything that happened, too.” I first became interested in autobiographical comics and graphic novels after reading some of Jeffrey Brown’s comics in 2005. There was something about his loose, sketchbook-style illustrations that made his work accessible to a newly minted comics fan such as myself. There were no superpowers, no buxom women and no maniacal villains in his comics… just real stories. Right when I was on the brink of exhausting Brown’s catalogue, Peter Birkemoe, the co-owner of The Beguiling1, suggested that I expand my interests. When he rang up my latest purchase, he said, “If you like this stuff, you should try reading some John Porcellino.” I promptly swept up Porcellino’s King-Cat Classix: The Best of King-Cat Comics and Stories and I soon discovered other autobiographical cartoonists including Chester Brown, Joe Matt, Lucy Knisley and Harvey Pekar. -

Exhibitor Resources & Information

A VISION FOR ALL TEXANS VIRTUAL Exhibitor Resources & Information TLA Virtual 2020 | Exhibitor Resources & Information Welcome! I want to thank our exhibitors and TLA held its annual in-person sponsors so much for continuing to conference for more than 100 years; support the Texas Library Association only a historic epidemic prevented us and Texas libraries during this from coming together. We appreciate challenging and unprecedented time. our exhibitors and sponsors’ support now more than ever, and look forward I’m amazed at the wealth of resources to coming together with everyone for they are offering to TLA 2020 Virtual TLA 2021 in San Antonio. attendees. From author videos to free downloads, ARCs to guides, posters, event kits and more, I know our members will be just as impressed as I am with the quality and breadth of their Cecilia Barham publications and products, both virtual 2019-2020 TLA President, Director, and in print. And the students, teachers, North Richland Hills Library parents and community patrons who rely on you will benefit from their generosity as well. ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: TLA 2020 Exhibits Directory includes a list of all exhibitors and company descriptions TLA 2020 Conference app #ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPRSTUVWZ Click on a letter to jump to those listings 2 TLA Virtual 2020 | Exhibitor Resources & Information Thank You to Our 2020 Sponsors LEGACY PRESIDENT’S PARTNER CIRCLE DIAMOND PLATINUM GOLD SILVER BRONZE #ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPRSTUVWZ Click on a letter to jump to those listings 3 TLA Virtual 2020 | Exhibitor Resources -

2010 1:22 PM Page 1

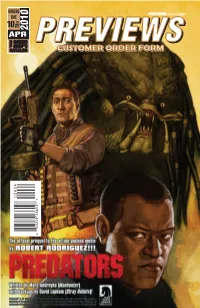

April 10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 3/18/2010 1:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 10APR 2010 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG Project7:Layout 1 3/15/2010 1:35 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Apr:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/18/2010 2:07 PM Page 1 PREDATORS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUZZARD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN ARROW #1 DC COMICS SUPERMAN #700 DC COMICS JURASSIC PARK: REDEMPTION #1 IDW PUBLISHING HACK/SLASH: MY FIRST MANIAC #1 MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH IMAGE COMICS THE BULLETPROOF COFFIN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD MAGAZINE #226 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #634 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/18/2010 2:14 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS 1 THE ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ #1 G AMAZE INK/ SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS CRITICAL MILLENNIUM #1 G ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC DARKWING DUCK: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS DISNEY‘S ALICE IN WONDERLAND GN/HC G BOOM! STUDIOS RED SONJA #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STARGATE: DANIEL JACKSON #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 GHOSTOPOLIS SC/HC G GRAPHIX THE WHISPERS IN THE WALLS #1 G HUMANOIDS INC STARDROP VOLUME 1 GN G I BOX PUBLISHING KRAZY KAT: A CELEBRATION OF SUNDAYS HC G SUNDAY PRESS BOOKS SIMON & KIRBY SUPERHEROES HC G TITAN PUBLISHING THE PLAYWRIGHT HC G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS CHARMED #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES WILLIAM STOUT: HALLUCINATIONS SC/HC G ART BOOKS 2 SUCK IT, WONDER WOMAN! MISADVENTURES OF A HOLLYWOOD GEEK G HUMOR ASLAN: THE PIN-UP SC G INTERNATIONAL STAR WARS: THE OFFICIAL FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE G STAR WARS TOYFARE #156 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CALENDARS 2 BONE 2011 WALL CALENDAR G COMICS VINTAGE -

Comic Book Coloring Stricciones Y Creatividad” Titles Include: Bizarro Comics (DC), Nick- Festival ÑAM, Palencia, Spain, October 5, 2014

Matt Madden curriculum vitae areas of expertise contact • comics La maison des auteurs • art education 2 Bd Aristide Briand • comics criticism 16000 Angoulême • translation from French and Spanish France [email protected] +33 (0)6 80 67 55 80 teaching experience www.mattmadden.com faculty positions education Université de Picardie Jules Verne à Amiens University of Texas at Austin, May 1996 2013-2015 Austin, Texas USA Designed and led workshops teaching basics of cartooning language M.A., Foreign Language Education (TEFL) and skills to students in comics degree program. University of Michigan, May 1990 School of Visual Arts, 209 East 23 St., New York NY Ann Arbor, Michigan USA fall 2001-2012 B.A., Comparative Literature Classes taught include full year “Storytelling” class, a class on experimental comics, and a continuing education class, “Comics memberships & distinctions Storytelling” as well as a monthly seminar. Develop own syllabi and course materials. Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres Paid consultant on curriculum development for Division of 2012 Continuing Education comics classes. Conseil d’Orientation de la Cité Internatio- nale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image Eugene Lang College, The New School, 65 West 11th Street, New 2013-present York NY Comics Committee, Brooklyn Book Festival Spring 2007 2011-present Taught intensive workshop class on comics storytelling to Advisor, Sequential Artists Workshop humanities and art students. 2010-present Member, OuBaPo, Workshop for Potential Comics Yale University, New Haven CT 2002- present summer 2004 National Association of Comics Art Educators Created and taught five-week intensive course called “Comics 2002-present Storytelling” taught in the English Department as part of Yale Graphic Artists Guild Summer Programs. -

Web Resources the Following Is a List of Web Resources Mentioned Throughout This YA Hotline, with Useful Additions. Beyond the F

Web Resources The following is a list of web resources mentioned throughout this YA Hotline, with useful additions. Beyond the Funnies http://www.collectionscanada.ca/comics/index-e.html comix.@$#!; A Graphic Novel http://www.calbook.org/Programs/Comix/ Discussion Program for Teens Comic Book Awards Almanac http://users.rcn.com/aardy/comics/awards/ Comic Book Legal Defense Fund www.cbldf.org/ Comic Book Resources http://vvww.comicbookresources.com/ Comic Books for Young Adults http://ublib.buffalo.eduilml/comics/pages/ Comic Book Movies http://www.comicbookmovie.com/ Comics Continuum http://comicscontinuum.com/ The Comics Journal http://www.tcj.com/ Comics to Film http://vvvvw.comics2film.com/ Decimal Classification Editorial http://www.ocic.orgidewey/discussion/papers/GraphicTestNov2004.htm Policy Committee:statement on shelving graphic novels The Diamond Bookshelf http://bookshelf.diamondcomics.com +Drawn & Quarterly http://www.drawnandquarterly.com/ Eisner Awards http://vvww.comic-con.org/cci/ccieisners_main.shtml Fantagraphics Books http://www.fantagraphics.com/ Friends of Lulu http://www.friends-lulu.org/ Graphic Novels in Libraries Listery http://www.angelfire.com/comics/gnlib/ Harvey Awards www.harveyawards.org lbox Publishing (Home to Thieves www.iboxpublishing.com and Kings GN) Ignatz Awards http://www.spxpo.com/ignatz.shtml Japan's Media Arts Festival Awards http://plaza.bunka.go.jpienglishfiestival.html Newsarama http://wvvw.newsarama.com/ Newtype USA http://www.newtype-usa.com New York Public Library Guide to http://www.nypl.org/research/chss/grd/resguides/comic/ -

ALA ANNUAL 2010 EXHIBITOR LIST As of 6-2-10

ALA ANNUAL 2010 EXHIBITOR LIST As of 6-2-10 Company Name Booth 3M Library Systems 1703 America Reads Spanish 3025 A Fashion Hayvin, Inc. 3560 American Collective Stand 3108 AAAS/SB&F 4214 American Geological Institute 1111 Abbeville Press, Inc. 2752 American Interfile & Library ABC-CLIO 3725 Relocations 4062 ABDO Publishing - Spotlight - Magic American Psychological Association 3131 Wagon - ABDO iBooks 3109 American Public Health Association 2346 ABI Professional Amicus 2964 Publications/Vandamere Press 4132 Annick Press 2809 Abingdon Press 1033 Anup Research And Multimedia USA Abrams/Amulet/STC. 2732 Health and Wellness Management Abu Dhabi International Book Fair 3108 Including Diabetes, High Blood Accessible Archives 4047 Pressure, High Cholestrol, Heart Problem, Asthma, Women Health and AccuCut 2838 Many More 4231 Ackermann Kunstverlag 3124 Anvil Publishing 1026 Acorn Media 3118 AP Images from AccuWeather 2009 Action! Library Media Service 2560 Arcadia Publishing 4105 Actrace 1428 Arsenal Pulp Press 2833 Adam Matthew Digital 4005 Arte Publico Press 2643 aha! Chinese Inc. 4242 Artisan Books (A division of Workman Agati, Inc. 3515 Publishing Company) 2701 ALA Membership Pavilion 2424 ARTstor 3937 ALA Public Programs Office 2659 Asia for Kids/Culture for Kids/Master ALA Publishing 2605 Comm 2450 ALA/ Affiliate Members 2533 Association of College & Research Libraries 2439 ALA/AFL-CIO 4040 Association of Research Libraries: Albert Whitman & Company 2616 LibQUAL+ & StatsQUAL 3853 Alexander Street Press 3813 Atiz Innovation, Inc. 1032 Alexandria 1208 Atlas Systems 3825 Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill (A division of Workman Publishing Audio Bookshelf 2541 Company) 2701 Audio Editions Books On Cassette & CD 3340 Alibris 3548 Author Solutions, Inc.