Covered Call Options: a Proposal to Ease LDC Debt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES SAMPLE QUESTIONS Q1. a Strangle Is an Investment Strategy That Combines A. a Call and a Put for the Same

FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES SAMPLE QUESTIONS Q1. A strangle is an investment strategy that combines a. A call and a put for the same expiry date but at different strike prices b. Two puts and one call with the same expiry date c. Two calls and one put with the same expiry dates d. A call and a put at the same strike price and expiry date Answer: a. Q2. A trader buys 2 June expiry call options each at a strike price of Rs. 200 and Rs. 220 and sells two call options with a strike price of Rs. 210, this strategy is a a. Bull Spread b. Bear call spread c. Butterfly spread d. Calendar spread Answer c. Q3. The option price will ceteris paribus be negatively related to the volatility of the cash price of the underlying. a. The statement is true b. The statement is false c. The statement is partially true d. The statement is partially false Answer: b. Q 4. A put option with a strike price of Rs. 1176 is selling at a premium of Rs. 36. What will be the price at which it will break even for the buyer of the option a. Rs. 1870 b. Rs. 1194 c. Rs. 1140 d. Rs. 1940 Answer b. Q5 A put option should always be exercised _______ if it is deep in the money a. early b. never c. at the beginning of the trading period d. at the end of the trading period Answer a. Q6. Bermudan options can only be exercised at maturity a. -

G85-768 Basic Terminology for Understanding Grain Options

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension Extension 1985 G85-768 Basic Terminology For Understanding Grain Options Lynn H. Lutgen University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Lutgen, Lynn H., "G85-768 Basic Terminology For Understanding Grain Options" (1985). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 643. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/643 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. G85-768-A Basic Terminology For Understanding Grain Options This publication, the first of six NebGuides on agricultural grain options, defines many of the terms commonly used in futures trading. Lynn H. Lutgen, Extension Marketing Specialist z Grain Options Terms and Definitions z Conclusion z Agricultural Grain Options In order to properly understand examples and literature on options trading, it is imperative the reader understand the terminology used in trading grain options. The following list also includes terms commonly used in futures trading. These terms are included because the option is traded on an underlying futures contract position. It is an option on the futures market, not on the physical commodity itself. Therefore, a producer also needs a basic understanding of the futures market. GRAIN OPTIONS TERMS AND DEFINITIONS AT-THE-MONEY When an option's strike price is equal to, or approximately equal to, the current market price of the underlying futures contract. -

Futures and Options Workbook

EEXAMININGXAMINING FUTURES AND OPTIONS TABLE OF 130 Grain Exchange Building 400 South 4th Street Minneapolis, MN 55415 www.mgex.com [email protected] 800.827.4746 612.321.7101 Fax: 612.339.1155 Acknowledgements We express our appreciation to those who generously gave their time and effort in reviewing this publication. MGEX members and member firm personnel DePaul University Professor Jin Choi Southern Illinois University Associate Professor Dwight R. Sanders National Futures Association (Glossary of Terms) INTRODUCTION: THE POWER OF CHOICE 2 SECTION I: HISTORY History of MGEX 3 SECTION II: THE FUTURES MARKET Futures Contracts 4 The Participants 4 Exchange Services 5 TEST Sections I & II 6 Answers Sections I & II 7 SECTION III: HEDGING AND THE BASIS The Basis 8 Short Hedge Example 9 Long Hedge Example 9 TEST Section III 10 Answers Section III 12 SECTION IV: THE POWER OF OPTIONS Definitions 13 Options and Futures Comparison Diagram 14 Option Prices 15 Intrinsic Value 15 Time Value 15 Time Value Cap Diagram 15 Options Classifications 16 Options Exercise 16 F CONTENTS Deltas 16 Examples 16 TEST Section IV 18 Answers Section IV 20 SECTION V: OPTIONS STRATEGIES Option Use and Price 21 Hedging with Options 22 TEST Section V 23 Answers Section V 24 CONCLUSION 25 GLOSSARY 26 THE POWER OF CHOICE How do commercial buyers and sellers of volatile commodities protect themselves from the ever-changing and unpredictable nature of today’s business climate? They use a practice called hedging. This time-tested practice has become a stan- dard in many industries. Hedging can be defined as taking offsetting positions in related markets. -

Buying Options on Futures Contracts. a Guide to Uses

NATIONAL FUTURES ASSOCIATION Buying Options on Futures Contracts A Guide to Uses and Risks Table of Contents 4 Introduction 6 Part One: The Vocabulary of Options Trading 10 Part Two: The Arithmetic of Option Premiums 10 Intrinsic Value 10 Time Value 12 Part Three: The Mechanics of Buying and Writing Options 12 Commission Charges 13 Leverage 13 The First Step: Calculate the Break-Even Price 15 Factors Affecting the Choice of an Option 18 After You Buy an Option: What Then? 21 Who Writes Options and Why 22 Risk Caution 23 Part Four: A Pre-Investment Checklist 25 NFA Information and Resources Buying Options on Futures Contracts: A Guide to Uses and Risks National Futures Association is a Congressionally authorized self- regulatory organization of the United States futures industry. Its mission is to provide innovative regulatory pro- grams and services that ensure futures industry integrity, protect market par- ticipants and help NFA Members meet their regulatory responsibilities. This booklet has been prepared as a part of NFA’s continuing public educa- tion efforts to provide information about the futures industry to potential investors. Disclaimer: This brochure only discusses the most common type of commodity options traded in the U.S.—options on futures contracts traded on a regulated exchange and exercisable at any time before they expire. If you are considering trading options on the underlying commodity itself or options that can only be exercised at or near their expiration date, ask your broker for more information. 3 Introduction Although futures contracts have been traded on U.S. exchanges since 1865, options on futures contracts were not introduced until 1982. -

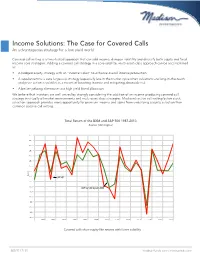

Income Solutions: the Case for Covered Calls an Advantageous Strategy for a Low-Yield World

Income Solutions: The Case for Covered Calls An advantageous strategy for a low-yield world Covered call writing is a time-tested approach that can add income, dampen volatility and diversify both equity and fixed income core strategies. Adding a covered call strategy in a core-satellite, multi-asset-class approach can be accomplished as: • A hedged equity strategy with an “income kicker” to enhance overall income production • A supplement to a core large-cap strategy (especially late in the market cycle when valuations are long-in-the-tooth and price action is volatile) as a means of boosting income and mitigating downside risk • A better-yielding alternative to a high yield bond allocation We believe that investors are well-served by strongly considering the addition of an income-producing covered call strategy in virtually all market environments and multi-asset class strategies. Madison’s active call writing/active stock selection approach provides more opportunity for premium income and alpha from underlying security selection than common passive call writing. Total Return of the BXM and S&P 500 1987-2013 Rolling Returns Source: Morningstar Time Period: 1/1/1987 to 12/31/2013 Rolling Window: 1 Year 1 Year shift 40.0 35.0 30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 Return 0.0 S&P 500 -5.0 -10.0 CBOE S&P 500 Buywrite BXM -15.0 -20.0 -25.0 -30.0 -35.0 -40.0 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 S&P 500 TR USD Covered calls show equity-likeCBOE returns S&P 500 with Buyw ritelower BXM volatility Source: Morningstar Direct 888.971.7135 madisonfunds.com | madisonadv.com Covered Call Strategy(A) Benefits of Individual Stock Options vs. -

Structured Products in Asia

2015 ISSUE: NOVEMBER Structured Products in Asia hubbis.com 1st Leonteq has received more than 20 awards since its foundation in 2007 THE QUINTESSENCE OF OUR MISSION STATEMENT LET´S REDEFINE YOUR INVESTMENT EXPERIENCE Leonteq’s explicit goal is to make a difference through particular transparency in structured investment products and to be the preferred technology and service partner for investment solutions. We count on experienced industry experts with a focus on achieving client’s goals and a fi rst class IT infrastructure, setting new stand- ards in stability and fl exibility. OUR DIFFERENTIATION Modern platform • Integrated IT platform built from ground up with a focus on automation of key processes in the value chain • Platform functionality to address increased customer demand for transparency, service, liquidity, security and sustainability Vertical integration • Control of the entire value chain as a basis for proactive service tailored to specifi c needs of clients • Automation of key processes mitigating operational risks Competitive cost per issued product • Modern platform resulting in a competitive cost per issued product allowing for small ticket sizes LEGAL DISCLAIMER Leonteq Securities (Hong Kong) Limited (CE no.AVV960) (“Leonteq Hong Kong”) is responsible for the distribution of this publication in Hong Kong. It is licensed and regulated by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission for Types 1 and 4 regulated activities. The services and products it provides are available only to “profes- sional investors” as defi ned in the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) of Hong Kong. This document is being communicated to you solely for the purposes of providing information regarding the products and services that the Leonteq group currently offers, subject to applicable laws and regulations. -

Show Me the Money: Option Moneyness Concentration and Future Stock Returns Kelley Bergsma Assistant Professor of Finance Ohio Un

Show Me the Money: Option Moneyness Concentration and Future Stock Returns Kelley Bergsma Assistant Professor of Finance Ohio University Vivien Csapi Assistant Professor of Finance University of Pecs Dean Diavatopoulos* Assistant Professor of Finance Seattle University Andy Fodor Professor of Finance Ohio University Keywords: option moneyness, implied volatility, open interest, stock returns JEL Classifications: G11, G12, G13 *Communications Author Address: Albers School of Business and Economics Department of Finance 901 12th Avenue Seattle, WA 98122 Phone: 206-265-1929 Email: [email protected] Show Me the Money: Option Moneyness Concentration and Future Stock Returns Abstract Informed traders often use options that are not in-the-money because these options offer higher potential gains for a smaller upfront cost. Since leverage is monotonically related to option moneyness (K/S), it follows that a higher concentration of trading in options of certain moneyness levels indicates more informed trading. Using a measure of stock-level dollar volume weighted average moneyness (AveMoney), we find that stock returns increase with AveMoney, suggesting more trading activity in options with higher leverage is a signal for future stock returns. The economic impact of AveMoney is strongest among stocks with high implied volatility, which reflects greater investor uncertainty and thus higher potential rewards for informed option traders. AveMoney also has greater predictive power as open interest increases. Our results hold at the portfolio level as well as cross-sectionally after controlling for liquidity and risk. When AveMoney is calculated with calls, a portfolio long high AveMoney stocks and short low AveMoney stocks yields a Fama-French five-factor alpha of 12% per year for all stocks and 33% per year using stocks with high implied volatility. -

Straddles and Strangles to Help Manage Stock Events

Webinar Presentation Using Straddles and Strangles to Help Manage Stock Events Presented by Trading Strategy Desk 1 Fidelity Brokerage Services LLC ("FBS"), Member NYSE, SIPC, 900 Salem Street, Smithfield, RI 02917 690099.3.0 Disclosures Options’ trading entails significant risk and is not appropriate for all investors. Certain complex options strategies carry additional risk. Before trading options, please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, and call 800-544- 5115 to be approved for options trading. Supporting documentation for any claims, if applicable, will be furnished upon request. Examples in this presentation do not include transaction costs (commissions, margin interest, fees) or tax implications, but they should be considered prior to entering into any transactions. The information in this presentation, including examples using actual securities and price data, is strictly for illustrative and educational purposes only and is not to be construed as an endorsement, or recommendation. 2 Disclosures (cont.) Greeks are mathematical calculations used to determine the effect of various factors on options. Active Trader Pro PlatformsSM is available to customers trading 36 times or more in a rolling 12-month period; customers who trade 120 times or more have access to Recognia anticipated events and Elliott Wave analysis. Technical analysis focuses on market action — specifically, volume and price. Technical analysis is only one approach to analyzing stocks. When considering which stocks to buy or sell, you should use the approach that you're most comfortable with. As with all your investments, you must make your own determination as to whether an investment in any particular security or securities is right for you based on your investment objectives, risk tolerance, and financial situation. -

Empirical Properties of Straddle Returns

EDHEC RISK AND ASSET MANAGEMENT RESEARCH CENTRE 393-400 promenade des Anglais 06202 Nice Cedex 3 Tel.: +33 (0)4 93 18 32 53 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.edhec-risk.com Empirical Properties of Straddle Returns December 2008 Felix Goltz Head of applied research, EDHEC Risk and Asset Management Research Centre Wan Ni Lai IAE, University of Aix Marseille III Abstract Recent studies find that a position in at-the-money (ATM) straddles consistently yields losses. This is interpreted as evidence for the non-redundancy of options and as a risk premium for volatility risk. This paper analyses this risk premium in more detail by i) assessing the statistical properties of ATM straddle returns, ii) linking these returns to exogenous factors and iii) analysing the role of straddles in a portfolio context. Our findings show that ATM straddle returns seem to follow a random walk and only a small percentage of their variation can be explained by exogenous factors. In addition, when we include the straddle in a portfolio of the underlying asset and a risk-free asset, the resulting optimal portfolio attributes substantial weight to the straddle position. However, the certainty equivalent gains with respect to the presence of a straddle in a portfolio are small and probably do not compensate for transaction costs. We also find that a high rebalancing frequency is crucial for generating significant negative returns and portfolio benefits. Therefore, from an investor's perspective, straddle trading does not seem to be an attractive way to capture the volatility risk premium. JEL Classification: G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions, G12 - Asset Pricing, G13 - Contingent Pricing EDHEC is one of the top five business schools in France. -

EC3070 FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES GLOSSARY Ask Price the Bid Price

EC3070 FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES GLOSSARY Ask price The bid price. Arbitrage An arbitrage is a financial strategy yielding a riskless profit and requiring no investment. It commonly amounts to the successive purchase and sale, or vice versa, of an asset at differing prices in different markets. i.e. it involves buying cheap and selling dear or selling dear and buying cheap. Bid A bid is a proposal to buy. A typical convention for vocalising a bid is “p for n”: p being the proposed unit price and n being the number of units or contracts demanded. Backwardation Backwardation describes a situation where the amount of money required for the future delivery of an item is lower than the amount required for immediate delivery. Backwardation is a signal that the item in question is in short supply. The opposite market condition to backwardation is known as contango, which is when the spot price is lower than the futures price. In fact, there is some ambiguity in the usage of the term. According to the definition above, backwardation is when Fτ|0 <S0, where Fτ|0 is the current price for a delivery at time τ and S0 is the current spot price. In an alternative definition, backwardation exists when Fτ|0 <E(Fτ|t) with 0 <t<τ, which is when the expected future price at a later date exceeds the futures price settled at time t = 0. In modern usage, this is called normal backwardation. Buyer A buyer is a long position holder who has agreed to accept the delivery of a commodity at some future date. -

Introduction to Options Mark Welch and James Mintert*

E-499 RM2-2.0 01-09 Risk Management Introduction To Options Mark Welch and James Mintert* Options give the agricultural industry a flexi- a put option can convert an option position into ble pricing tool that helps with price risk manage- a short futures position, established at the strike ment. Options offer a type of insurance against price, by exercising the put option. Similarly, the adverse price moves, require no margin deposits buyer of a call option can convert an option posi- for buyers, and allow buyers to participate in tion into a long futures position, established at favorable price moves. Commodity options are the strike price, by exercising the call option. The adaptable to a wide range of pricing situations. option buyer also can sell the option to someone For example, agricultural producers can use com- else or do nothing and let the option expire. The modity options to establish an approximate price choice of action is left entirely to the option buyer. floor, or ceiling, for their production or inputs. The option buyer obtains this right by paying the With today’s large price fluctuations, the financial premium to the option seller. payoff in controlling price risk and protecting What about the option seller? The option seller profits can be substantial. receives the premium from the option buyer. If the option buyer exercises the option, the option What is an Option? seller is obligated to take the opposite futures An option is simply the right, but not the position at the same strike price. Because of the obligation, to buy or sell a futures contract at seller’s obligation to take a futures position if the some predetermined price within a specified option is exercised, an option seller must post a time period. -

EQUITY DERIVATIVES Faqs

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SECURITIES MARKETS SCHOOL FOR SECURITIES EDUCATION EQUITY DERIVATIVES Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Authors: NISM PGDM 2019-21 Batch Students: Abhilash Rathod Akash Sherry Akhilesh Krishnan Devansh Sharma Jyotsna Gupta Malaya Mohapatra Prahlad Arora Rajesh Gouda Rujuta Tamhankar Shreya Iyer Shubham Gurtu Vansh Agarwal Faculty Guide: Ritesh Nandwani, Program Director, PGDM, NISM Table of Contents Sr. Question Topic Page No No. Numbers 1 Introduction to Derivatives 1-16 2 2 Understanding Futures & Forwards 17-42 9 3 Understanding Options 43-66 20 4 Option Properties 66-90 29 5 Options Pricing & Valuation 91-95 39 6 Derivatives Applications 96-125 44 7 Options Trading Strategies 126-271 53 8 Risks involved in Derivatives trading 272-282 86 Trading, Margin requirements & 9 283-329 90 Position Limits in India 10 Clearing & Settlement in India 330-345 105 Annexures : Key Statistics & Trends - 113 1 | P a g e I. INTRODUCTION TO DERIVATIVES 1. What are Derivatives? Ans. A Derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset. The underlying asset can be equity shares or index, precious metals, commodities, currencies, interest rates etc. A derivative instrument does not have any independent value. Its value is always dependent on the underlying assets. Derivatives can be used either to minimize risk (hedging) or assume risk with the expectation of some positive pay-off or reward (speculation). 2. What are some common types of Derivatives? Ans. The following are some common types of derivatives: a) Forwards b) Futures c) Options d) Swaps 3. What is Forward? A forward is a contractual agreement between two parties to buy/sell an underlying asset at a future date for a particular price that is pre‐decided on the date of contract.