Hospital Accountability Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harbin Clinic: Early Adoption of EMR Advantages and Challenges

The Harbin Clinic: Early Adoption of EMR Advantages and Challenges Introduction Dr. Ken Davis leaned back in his desk chair, one ankle hooked on his knee, and reflected on the events of his day. Once again, the decision had been made to make another big change at The Harbin Clinic in order to improve patient care. The Clinic had made the decision to move from their current electronic medical record (EMR)1 vendor and select new software, a new electronic medical record, and a new vendor. Dr. Davis, along with the Information Technology director, Angie McWhorter, had taken all things into consideration- the support staff, the size of the company, how dedicated the company would be to The Harbin Clinic, and whether the new technology would allow The Harbin Clinic to successfully comply with the federal government’s meaningful use mandate. When he accepted the position of CEO in 2002, Davis had told the board of directors that he would only do this for two years. And yet here he was, ten years later. Davis sighed to himself. He realized that while they had made many advancements in the past decade, in some ways the Harbin Clinic was about to face the same issues once again. While the physicians and staff were now accustomed to using an electronic medical record, the Clinic would still have to undergo another implementation process, one that would include many difficulties. Given the amount of pressure on him today, he could only imagine how Dr. Ferguson, his predecessor, had felt when he had made the decision to introduce electronic medical records into the daily operations of the Harbin Clinic for the first time in 1999. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama Southern Division

Case 2:11-cv-04099-RDP Document 12 Filed 03/20/13 Page 1 of 29 FILED 2013 Mar-20 PM 01:24 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION LAURA C. NOAH, } } Plaintiff, } } v. } Case No.: 2:11-CV-4099-RDP } MICHAEL J. ASTRUE, } COMMISSIONER OF } SOCIAL SECURITY, } } Defendant. } MEMORANDUM OF DECISION Plaintiff Laura C. Noah brings this action pursuant to Sections 205(g) and 1631(c)(3) of the Social Security Act (the “Act”) seeking review of the decision by the Commissioner of the Social Security Administration (“Commissioner”) denying her claim for Social Security Disability Insurance Benefits and Supplemental Security Income. (Doc. #1 at 1); see 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(g) and 1383(c). Based upon the court’s review of the record and the briefs submitted by the parties, the court finds that the decision of the Commissioner is due to be affirmed. I. Proceedings Below This action arises from Plaintiff’s applications for Social Security Disability Insurance Benefits (“DIB”) and Supplemental Security Income (“SSI”), filed November 18, 2008, alleging disability beginning on December 22, 2005,1 four days before she stopped working as a waitress at a Waffle House. (Tr. 131, 40). Both claims were denied on January 7, 2009. (Tr. 79). Plaintiff then requested and received a hearing before Administrative Law Judge Jill Lolley Vincent on August 12, 2010 in Birmingham, Alabama. (Tr. 34). In her decision, dated 1 This is Plaintiff’s third application alleging disability beginning on December 22, 2005. -

Powerpoint Arcs (Ppt)

Medical Staff Orientation Welcome to the Floyd Health System Your orientation to the Floyd Health System includes meetings with designated resource people, facility tours and written materials. The resource people and your assigned orientation facilitator are available to answer any questions you may have. You will be introduced to staff members and will become familiar with areas of the facility where you will be providing care and services. Clinical managers, clinical supervisors and staff of each area are available to assist you as you become familiar with our facilities. References to policies and guidelines may be found in the attached Appendix section at the end of this orientation file. At the end of the online portion of this orientation, you will be asked to verify that you have reviewed the information provided. Organizational Overview: Learning About Floyd Health System Learning About Floyd Health System Learning About Floyd Health System The Floyd Health System family of health care services includes Floyd Medical Center, Polk Medical Center, Floyd Cherokee Medical Center, Floyd Behavioral Health, Heyman HospiceCare, the Floyd Primary Care Network and numerous outpatient services. Learning About Floyd Health System Our service area covers Floyd, Polk, Chattooga, Bartow and Gordon counties in Georgia, and Calhoun and Cherokee counties in Alabama. Approximately 470,000 people live and work in these seven counties. Organizational Overview What Guides Us – Our Value Compass The four points of our Value Compass serve as a visual reminder of the areas that drive our efforts: patient satisfaction, strategy, finance and quality. At the center is “people.” These are our customers, their friends and family, our co-workers, our physicians, our volunteers and our vendors. -

Floyd Medical Center Policy and Procedure Manual Patient Financial Services

Page 1 of 8 FC-016 FLOYD MEDICAL CENTER POLICY AND PROCEDURE MANUAL PATIENT FINANCIAL SERVICES TITLE: Financial Assistance Policy Policy No.: FC-016 (FAP) Purpose: To set forth the eligibility criteria and Developed Date: 03/25/2013 process relating to Floyd Medical Center’s Review Date: 03/17/2021 provision of financial assistance to qualifying Revised Date: patients for emergency and other medically 11/10/2017,4/6/2018,7/30/2019,04/2020, 09/2020, necessary care. 03/2021 Review Responsibility: Revenue Cycle Reference Standards: IRC § 501(r) Policy: Floyd Medical Center will provide to qualifying patients free or discounted emergency and other medically necessary care in accordance with the eligibility criteria and determination processes set forth in this Policy. In addition, following a determination of a patient’s eligibility for financial assistance, Floyd Medical Center will not charge the patient more for emergency or other medically necessary care than the amounts generally billed to individuals who have insurance covering such care, as determined in accordance with this Policy. As further described below, this Financial Assistance Policy: 1. Includes the eligibility criteria for financial assistance and sets forth the circumstances in which a patient will qualify for free or discounted care. 2. Describes the basis for calculating amounts charged to patients eligible for financial assistance under this Policy, as well as the amounts to which discounts will be applied. 3. Limits the amounts that Floyd Medical Center will charge for emergency or other medically necessary care provided to patients eligible for financial assistance to no more than the amount generally billed to individuals who have insurance covering such care. -

Georgia Committee for Trauma Excellence

Georgia Committee for Trauma Excellence MEETING MINUTES Thursday November 8, 2018 Conference Call MEMBERS ON CALL REPRESENTING Liz Atkins, Chair Grady Memorial Gina Solomon, Past Chair Gwinnett MediCal Center Regina Medeiros, GTC Georgia Trauma Commission Kristal Smith, Injury Prevention NaviCent Health MediCal Center Anastasia Hartigan, PI DoCtors Hospital of Augusta Erin MoorCones, Education Grady Memorial Hospital OTHERS ON CALL REPRESENTING Amanda Wright Augusta University NanCy Friedel CHOA Egleston Jennifer Hutchinson CHOA at Scottish Rite Joni Napier Crisp Regional Hospital Janann Dunnavant Crisp Regional Hospital Farrah Parker DoCtor’s Hospital, HCA Gail Thornton Emanuel County Hospital Kristen Campbell Fairview Park Hospital Melissa Parris Floyd MediCal Center Katie Hasty Floyd MediCal Center Susan Campis Grady Burn Center Kenya Cosby Grady Burn Center Bernadette Frias Grady Memorial Hospital Elizabeth Williams Mays Grady Memorial Hospital Sarah Parker Grady Memorial Hospital Rayma Stephens Gwinnett MediCal Center RaChelle Bloom Gwinnett MediCal Center Colleen Horne Gwinnett MediCal Center Barlynda Bryant Gwinnett MediCal Center Georgia Committee of Trauma Excellence Meeting Minutes: 08 November 2018 Page 1 Kim Brown Hamilton MediCal Center Karrie Page Meadows Regional MiChele Benton Morgan Memorial University Tawnie Campbell NaviCent Health MediCal Center Josephine Fabico-Dulin NaviCent Health MediCal Center Jessica Mantooth Northeast Georgia MediCal Center Jesse Gibson Northeast Georgia MediCal Center Laura Wolf Northeast Georgia -

Gallbladder Removal

Patient Education Partners in Your Surgical Care AMericaN COLLege OF SUrgeoNS DIVisioN OF EDUcatioN Cholecystectomy Surgical Removal of the Gallbladder LaparoscopicLaparoscopic versus versus Open Open Cholecystectomy Cholecystectomy LLaparoscopicaparoscopic Cholecystectomy Cholecystectomy OpenOpen Cholecystectomy Cholecystectomy Patient Education This educational information is to help you be better informed about your operation and empower you with the skills and knowledge needed to actively participate in your care. Keeping You Informed Treatment Options Expectations Information that will help you further understand your operation. Surgery Before your operation— Evaluation usually Education is provided on: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy—The includes blood work, an gallbladder is removed with instruments abdominal ultrasound, Cholecystectomy Overview ............. 1 placed into 4 small slits in the abdomen. and an evaluation by your Condition, Symptoms, Tests ............ 2 Open cholecystectomy—The gallbladder surgeon and anesthesia Treatment Options ......................... 3 is removed through an incision on the provider to review your right side under the rib cage. health history and Risks and Possible Complications ..... 4 medications and to discuss Preparation and Expectations ......... 5 Nonsurgical pain control options. Your Recovery and Discharge ........... 6 Stone retrieval The day of your operation— Pain Control .................................. 7 For gallstones without symptoms You will not eat or drink for at least 4 hours -

March 6, 2019 – March 12, 2019 Need Projection Analyses

Use the links below for easy navigation Letters of Intent Letters of Intent - Expired New CON Applications Pending/Complete Applications Pending Review/Incomplete CON Applications Office of Health Planning Recently Approved CON Applications Recently Denied CON Applications Appealed CON Projects Letters of Determination Requests for Miscellaneous Letters of Determination Appealed Determinations DET Review LNR Conversion Requests for LNR for Diagnostic or Therapeutic Equipment Requests for LNR for Establishment CERTIFICATE OF NEED of Physician-Owned Ambulatory Surgery Facilities Appealed LNRs Requests for Extended Implementation/Performance Period Batching Notifications - Fall March 6, 2019 – March 12, 2019 Need Projection Analyses New Batching Review Winter Cycle Fall Cycle Non-Filed or Incomplete Surveys Georgia Department of Community Health Office of Health Planning Indigent-Charity Shortfalls 2 Peachtree Street 5th Floor CON Filing Requirements (effective July 18, 2017) Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3159 Contact Information (404) 656-0409 (404) 656-0442 Fax Verification of Lawful Presence within U.S. www.dch.georgia.gov Periodic Reporting Requirements CON Thresholds Open Record Request Form Web Links Certificate of Need Appeal Panel www.GaMap2Care.info Letters of Intent LOI2019010 Tanner Imaging Center, Inc. Development of Freestanding Imaging Center on Tanner Medical Center-Carrollton Campus Received: 2/15/2019 Application must be submitted on: 3/18/2019 Site: 706 Dixie Street, Carrollton, GA 30117 (Carroll County) Estimated Cost: $2,200,000 -

FLOYD Health System Disaster Management Physician Responsibilities

FLOYD Health System Disaster Management Physician Responsibilities The Medical Staff of Floyd Medical Center, Polk Medical Center and Floyd Cherokee Medical Center participate in internal and external disaster drills (or real-world events) affecting the hospital in order to ensure continuous and safe delivery of health care services. Please take an opportunity to review this information and familiarize yourself prior to a disaster occurring. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact: Floyd Medical Center Sheila Bennett, Executive Vice President; Chief of Patient Services at 706.509.6900 or Ben Rigas, Floyd Medical Center Safety Officer/Emergency Preparedness Coordinator at 706.509.6823 Polk Medical Center Tifani Kinard, Administrator/CNO at 770.749.4202 or Tim McElwee, Polk Medical Center Safety Officer/Emergency Preparedness Coordinator at 770.749.4232 Floyd Cherokee Medical Center David Early, Administrator at 706.509.6177/ 256.927.1311 or Josh Garmany, Floyd Cherokee Medical Center Safety Officer/Emergency Preparedness Coordinator at 256.927.1417. PROCEDURE: 1. The Executive Leader and/or Medical Staff President are notified by the Incident Commander or their designee to activate the call roster of the Medical Staff. 2. The Executive Leader, in conjunction with the Medical Staff Officer, notifies the Medical Staff as follows: ♦ Medical Staff President/Medical Staff President Elect ♦ Department Chairs ♦ Medical Directors ♦ Alphabetically calls the Medical Staff 3. The Executive Leader, Medical Staff President or designee will assume the responsibilities of Medical Staff Director for the Emergency Operations Center upon notification form the Incident Commander 4. The Executive Leader, Medical Staff President or designee reports directly to the Labor Pool area (Physician’s Lounge). -

Behind the 2017 Report to the Community Welcome Behind the Green

GreenBehind the 2017 Report to the Community Welcome Behind the Green Seventy-five years ago, Floyd Hospital opened its doors as the community hospital for Rome and Floyd County. An entire election centered on the call for a facility that would provide care to all comers in a post-Depression, World War II-wary community. That mission continues today. Seventy-five years later, the Floyd health system still maintains that mission and commitment to community leadership, even as it has grown to include multiple hospitals, a Primary Care network and a Family Medicine Residency program. Over the years Floyd has been a catalyst for growth and, today, it continues to be an economic engine for northwest Georgia as the county’s largest employer. Behind the Green is a review of the people, programs and compassionate acts over the past year that help tell the Floyd story. We are a not-for-profit community hospital, but what does that mean? It means we invest in our community by working in our schools and industries, by educating and screening our neighbors and by adding services and improving our facilities. And, we do all of that with a heart of compassion that you’ll read about in the pages that follow. You’ll also discover an important number, $72.8 million, which is the total cost of care Floyd and Polk provided to people in our community who could not afford to pay for their own care. On this page are elements that we assembled over the past two years to tell our 75-year story. -

A Roadmap for Recognizing, Evaluating, and Treating

Getting Tissue for Molecular Testing: An NSCLC Strategic Initiative Activity Summary Date: Jan, 2015 CME Credit Provider: Temple University School of Medicine Collaborators: Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), Fox Chase Cancer Center, and MCM Education Grant Supporter: Pfizer Start Date: March, 2013 End Date: Jan, 2015 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Planning Committee: .................................................................................................................................... 3 Learning Objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Participating Cancer Centers ......................................................................................................................... 3 QI Initiative Design ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Molecular Testing Rates: Pre (Baseline) vs. Post (Follow-Up) ...................................................................... 5 QI Summary of Centers ................................................................................................................................ -

2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Forward

2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Forward loyd Medical Center is committed to the health of members in our service area. This This Community Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) was completed in May 2019 to provide Health Needs F a snapshot of the health of Floyd’s primary service area, which includes Floyd, Polk and Assessment (CHNA) Chattooga counties in northwest Georgia and Cherokee County in northeast Alabama. was completed in May 2019 This document was developed in compliance with IRS 501(r) guidelines, incorporating input to provide a snapshot of the from community stakeholders and public health experts. The decision data used in this health of Floyd’s primary service assessment was resourced from publicly reported aggregated health information and internally area, which includes Floyd, generated statistical information. The data was then extrapolated to identify the health needs of Polk and Chattooga counties this community. This information is publicly available and may be used by diverse stakeholders in northwest Georgia in our community to address identified health needs, either individually or in partnership with and Cherokee County in others. The data presented in the Floyd Medical Center CHNA will be updated every three years northeast Alabama. and will be available for public inspection and comment. 2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 2 About Floyd ...................................................................................... -

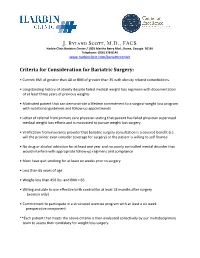

J. Ryland Scott, M.D., FACS

J. Ryland Scott, M.D., FACS Harbin Clinic Bariatric Center / 1825 Martha Berry Blvd., Rome, Georgia 30165 Telephone: (706) 378-8140 www.harbinclinic.com/bariatriccenter Criteria for Consideration for Bariatric Surgery: • Current BMI of greater than 40 or BMI of greater than 35 with obesity related comorbidities. • Longstanding history of obesity despite failed medical weight loss regimens with documentation of at least three years of previous weights • Motivated patient that can demonstrate a lifetime commitment to a surgical weight loss program with nutritional guidelines and follow-up appointments • Letter of referral from primary care physician stating that patient has failed physician supervised medical weight loss efforts and is motivated to pursue weight loss surgery • Verification from insurance provider that bariatric surgery consultation is a covered benefit (i.e. will the provider even consider coverage for surgery) or the patient is willing to self finance • No drug or alcohol addiction for at least one year and no poorly controlled mental disorder that would interfere with appropriate follow-up regimens and compliance • Must have quit smoking for at least six weeks prior to surgery • Less than 65 years of age • Weighs less than 450 lbs. and BMI < 65. • Willing and able to use effective birth control for at least 18 months after surgery (women only) • Commitment to participate in a structured exercise program with at least a six week preoperative component **Each patient that meets the above criteria is then evaluated collectively