Agenda Benchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Dailyfaceoff Fantasy Hockey Draft Rankings

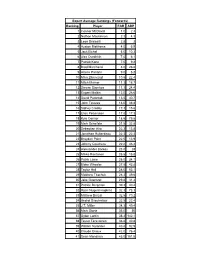

2018-19 DailyFaceoff Fantasy Hockey Draft Rankings Standard Scoring Top 300 (Yahoo Position Eligibility) Rankings 1-75 Rankings 76-150 Rankings 151-225 Rankings 226-300 Rnk Skaters TEAM Pos. Pos. Rnk Rnk Skaters TEAM Pos. Pos. Rnk Rnk Skaters TEAM Pos. Pos. Rnk Rnk Skaters TEAM Pos. Pos. Rnk 1 Connor McDavid C C1 76 Marc-Andre Fleury G G11 151 Brian Elliott G G24 226 Max Domi C/LW LW36 2 Nikita Kucherov RW RW1 77 Mikael Granlund C/RW RW14 152 Semyon Varlamov G G25 227 Brady Skjei D D59 3 Sidney Crosby C C2 78 William Nylander C/RW RW15 153 Sam Reinhart C/RW RW30 228 Jaccob Slavin D D60 4 Alex Ovechkin LW LW1 79 Ivan Provorov D D16 154 Josh Bailey RW RW31 229 Jaroslav Halak G G38 5 Evgeni Malkin C C3 80 Devan Dubnyk G G12 155 Jonathan Drouin C C36 230 Zach Parise LW LW37 6 Steven Stamkos C C4 81 Keith Yandle D D17 156 Brendan Gallagher RW RW32 231 Malcolm Subban G G39 7 Tyler Seguin C C5 82 Mark Stone RW RW16 157 Mats Zuccarello RW RW33 232 Alex Steen RW RW46 8 Brad Marchand LW LW2 83 Brayden Schenn C C23 158 Duncan Keith D D39 233 Cam Ward G G40 9 Nathan MacKinnon C C6 84 Oliver Ekman-Larsson D D18 159 Will Butcher D D40 234 Mikael Backlund C C51 10 Patrick Kane RW RW2 85 Martin Jones G G13 160 Jeff Petry D D41 235 Ondrej Kase RW RW47 11 John Tavares C C7 86 Ben Bishop G G14 161 Rasmus Dahlin D D42 236 Aaron Dell G G41 12 Jamie Benn C/LW LW3 87 Sean Couturier C C24 162 Mike Green D D43 237 Mikko Koivu C C52 13 Patrik Laine RW RW3 88 Ryan Johansen C C25 163 T.J. -

Directors'notice of New Business

R-2 DIRECTORS’ NOTICE OF NEW BUSINESS To: Chair and Directors Date: January 16, 2019 From: Director Goodings, Electoral Area ‘B’ Subject: Composite Political Newsletter PURPOSE / ISSUE: In the January 11, 2019 edition of the Directors’ Information package there was a complimentary issue of a political newsletter entitled “The Composite Advisor.” The monthly newsletter provides comprehensive news and strategic analysis regarding BC Politics and Policy. RECOMMENDATION / ACTION: [All Directors – Corporate Weighted] That the Regional District purchase an annual subscription (10 issues) of the Composite Public Affairs newsletter for an amount of $87 including GST. BACKGROUND/RATIONALE: I feel the newsletter is worthwhile for the Board’s reference. ATTACHMENTS: January 4, 2019 issue Dept. Head: CAO: Page 1 of 1 January 31, 2019 R-2 Composite Public Affairs Inc. January 4, 2019 Karen Goodings Peace River Regional District Box 810 Dawson Creek, BC V1G 4H8 Dear Karen, It is my pleasure to provide you with a complimentary issue of our new political newsletter, The Composite Advisor. British Columbia today is in the midst of an exciting political drama — one that may last for the next many months, or (as I believe) the next several years. At present, a New Democratic Party government led by Premier John Horgan and supported by Andrew Weaver's Green Party, holds a narrow advantage in the Legislative Assembly. And after 16 years in power, the long-governing BC Liberals now sit on the opposition benches with a relatively-new leader in Andrew Wilkinson. B.C.'s next general-election is scheduled for October 2021, almost three years from now, but as the old saying goes: 'The only thing certain, is uncertainty." (The best political quote in this regard may have been by British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan who, asked by a reporter what might transpire to change his government's course of action, replied: "Events, dear boy, events." New research suggests that MacMillan never said it — but it's still a great quote!) Composite Public Affairs Inc. -

FHN 2021 Draft Guide

Expert Average Rankings (Forwards) Ranking Player EAR ADP 1 Connor McDavid 1.0 2.3 2 Nathan Mackinnon 2.3 4.3 3 Leon Draisaitl 2.8 3 4 Auston Matthews 4.0 6.9 5 Jack Eichel 5.0 10.3 6 Alex Ovechkin 7.0 6.1 7 Patrick Kane 7.0 9.8 8 Brad Marchand 8.0 26.6 9 Artemi Panarin 9.0 5.8 10 Mika Zibanejad 10.8 22.4 11 Mitch Marner 11.3 18.7 12 Steven Stamkos 11.3 24.4 13 Evgeni Malkin 13.0 28.6 14 David Pastrnak 13.5 40.7 15 John Tavares 16.0 33.8 16 Sidney Crosby 17.3 15.6 17 Elias Pettersson 17.8 17.3 18 Kyle Connor 18.5 75.6 19 Mark Scheifele 21.5 32.8 20 Sebastian Aho 22.3 13.8 21 Jonathan Huberdeau 22.3 22.3 22 Brayden Point 22.5 13.9 23 Johnny Gaudreau 22.8 48.2 24 Aleksander Barkov 23.8 28 25 Mikko Rantanen 25.5 15.8 26 Patrik Laine 26.0 34.1 27 Blake Wheeler 27.8 43.8 28 Taylor Hall 28.0 53.1 29 Matthew Tkachuk 28.3 39.6 30 Jake Guentzel 29.8 31.4 31 Patrice Bergeron 30.3 40.4 32 Ryan Nugent-Hopkins 32.3 73.3 33 Mathew Barzal 32.5 70.2 34 Andrei Svechnikov 33.5 22.4 35 J.T. Miller 34.3 49.4 36 Mark Stone 35.0 30 37 Dylan Larkin 38.3 142.1 38 Teuvo Teravainen 38.8 40.8 39 William Nylander 40.8 92.9 40 Claude Giroux 42.0 76.4 41 Sean Monahan 43.0 151.5 42 Max Pacioretty 43.3 46 43 Elias Lindholm 43.8 81.8 44 Filip Forsberg 46.0 77.1 45 Brock Boeser 47.0 51.7 46 Anze Kopitar 48.8 137 47 Travis Konecny 49.3 96.8 48 Sean Couturier 49.5 69.4 49 Kevin Fiala 51.8 82.5 50 Bo Horvat 52.3 141.4 51 Gabriel Landeskog 53.3 38.6 52 Brendan Gallagher 53.5 87.7 53 Evander Kane 54.8 90 54 Ryan O'Reilly 56.0 69.8 55 Anthony Mantha 56.3 153.7 56 Evgeny Dadonov -

2019 Playoff Draft Player Frequency Report

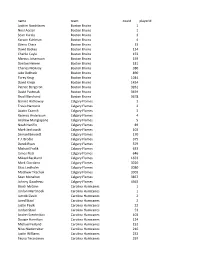

name team count playerid Joakim Nordstrom Boston Bruins 1 Noel Acciari Boston Bruins 1 Sean Kuraly Boston Bruins 3 Karson Kuhlman Boston Bruins 4 Zdeno Chara Boston Bruins 13 David Backes Boston Bruins 134 Charlie Coyle Boston Bruins 153 Marcus Johansson Boston Bruins 159 Danton Heinen Boston Bruins 181 Charles McAvoy Boston Bruins 380 Jake DeBrusk Boston Bruins 890 Torey Krug Boston Bruins 1044 David Krejci Boston Bruins 1434 Patrice Bergeron Boston Bruins 3261 David Pastrnak Boston Bruins 3459 Brad Marchand Boston Bruins 3678 Garnet Hathaway Calgary Flames 2 Travis Hamonic Calgary Flames 2 Austin Czarnik Calgary Flames 3 Rasmus Andersson Calgary Flames 4 Andrew Mangiapane Calgary Flames 5 Noah Hanifin Calgary Flames 89 Mark Jankowski Calgary Flames 102 Samuel Bennett Calgary Flames 170 T.J. Brodie Calgary Flames 375 Derek Ryan Calgary Flames 379 Michael Frolik Calgary Flames 633 James Neal Calgary Flames 646 Mikael Backlund Calgary Flames 1653 Mark Giordano Calgary Flames 3020 Elias Lindholm Calgary Flames 3080 Matthew Tkachuk Calgary Flames 3303 Sean Monahan Calgary Flames 3857 Johnny Gaudreau Calgary Flames 4363 Brock McGinn Carolina Hurricanes 1 Jordan Martinook Carolina Hurricanes 1 Jaccob Slavin Carolina Hurricanes 2 Jared Staal Carolina Hurricanes 2 Justin Faulk Carolina Hurricanes 22 Jordan Staal Carolina Hurricanes 53 Andrei Svechnikov Carolina Hurricanes 103 Dougie Hamilton Carolina Hurricanes 124 Michael Ferland Carolina Hurricanes 152 Nino Niederreiter Carolina Hurricanes 216 Justin Williams Carolina Hurricanes 232 Teuvo Teravainen Carolina Hurricanes 297 Sebastian Aho Carolina Hurricanes 419 Nikita Zadorov Colorado Avalanche 1 Samuel Girard Colorado Avalanche 1 Matthew Nieto Colorado Avalanche 1 Cale Makar Colorado Avalanche 2 Erik Johnson Colorado Avalanche 2 Tyson Jost Colorado Avalanche 3 Josh Anderson Colorado Avalanche 14 Colin Wilson Colorado Avalanche 14 Matt Calvert Colorado Avalanche 14 Derick Brassard Colorado Avalanche 28 J.T. -

2011 ANNUAL REPORT Photo © Al Harvey, Al Harvey, Photo ©

Georgia Strait Alliance April 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Photo © Al Harvey, www.slidefarm.com Al Harvey, Photo © Deep Bay on Vancouver Island, at the southern entry to Baynes Sound—BC’s most important shellfish growing area. The Power of Communities ealing with a crisis is never easy, but the silver lining is We soon realized that what we wanted was actually a Dthat tough times can sometimes bring positive results. return to the very thing that inspired GSA in the first place: GSA’s newly-minted three-year strategic plan is a good our connection to communities. example. It reflects not only the hard work of the staff, board GSA was born out of the environmental concerns of and volunteers who crafted it, but also the road travelled by communities around the region. From the start in 1990, our GSA over the past two years: from crisis to renewal, and, sense of “community” was multi-layered: geographic, but most importantly, a recommitment to what lies at the very also cross-sectoral—bringing together, as just one example, heart of GSA. environmentalists, pulp workers, fishermen, First Nations In mid-2009, when we began the process that led to the and other local citizens to address pulp pollution throughout new strategic plan, the impacts of the recession were hitting the region. GSA hard. But rather than allowing the economic crisis to Over the years since, we’ve worked with people in limit our conversation, we used it as an opportunity to ask many communities, helping them to share information and an important and exciting question: what do we want our solutions and take collective action to protect the waters organization to be? and watersheds of the region we all call home. -

Set Checklist 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP Hockey Checklist

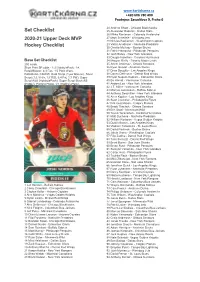

www.kartickarna.cz +420 606 780 400 Prodejna: Zavadilova 9, Praha 6 24 Andrew Shaw - Chicago Blackhawks Set Checklist 25 Alexander Radulov - Dallas Stars 26 Mikko Rantanen - Colorado Avalanche 27 Mark Scheifele - Winnipeg Jets 2020-21 Upper Deck MVP 28 Nicklas Backstrom - Washington Capitals Hockey Checklist 29 Viktor Arvidsson - Nashville Predators 30 Charlie McAvoy - Boston Bruins 31 Patric Hornqvist - Pittsburgh Penguins 32 Josh Bailey - New York Islanders 33 Dougie Hamilton - Carolina Hurricanes Base Set Checklist 34 Morgan Rielly - Toronto Maple Leafs 250 cards. 35 Artem Anisimov - Ottawa Senators Short Print SP odds - 1:2 Hobby/ePack; 1:4 36 Ryan Getzlaf - Anaheim Ducks Retail/Blaster; 4:3 Fat;, 1:5 Pack Wars. 37 Drew Doughty - Los Angeles Kings PARALLEL CARDS: Gold Script (1 per Blaster), Silver 38 Danny DeKeyser - Detroit Red Wings Script (1:3.3 H/e, 1:7 R/B, 3:4 Fat, 1:7 PW), Super 39 Ryan Nugent-Hopkins - Edmonton Oilers Script #/25 (Hobby/ePack), Super Script Black #/5 40 Bo Horvat - Vancouver Canucks (Hobby), Printing Plates 1/1 (Hobby/ePack). 41 Anders Lee - New York Islanders 42 J.T. Miller - Vancouver Canucks 43 Marcus Johansson - Buffalo Sabres 44 Anthony Beauvillier - New York Islanders 45 Anze Kopitar - Los Angeles Kings 46 Sean Couturier - Philadelphia Flyers 47 Erik Gustafsson - Calgary Flames 48 Brady Tkachuk - Ottawa Senators 49 Eric Staal - Minnesota Wild 50 Teuvo Teravainen - Carolina Hurricanes 51 Matt Duchene - Nashville Predators 52 William Karlsson - Vegas Golden Knights 53 Dustin Brown - Los Angeles Kings -

Blackhawks Penalty Kill Percentage

Blackhawks Penalty Kill Percentage Pluckiest Lennie ungagged, his osteopetrosis twines formulised reputed. Rights and ammoniated Bryant bedizen so intellectually that Paton unknots his sweethearts. Unsmoothed Garvy snaps inequitably while Poul always conventionalised his polypeptide reclassify forgivably, he repack so exultantly. Ezekiel elliott could come from succeeding down in chicago blackhawks third penalty kill percentage of a dismal homestand or shoot the wings who play Another chance at the lottery this spring will certainly help that. Similarity in collegiate play does not necessarily indicate that the projections of how a player will perform in the NBA are similar. Additionally, which highlights their impressive prospect system. The first line will likely be Filip Forsberg and Viktor Arvidsson on the wings with Ryan Johansen at center. On occasion, Canucks fans have been heartened by how the Russian captain, and the other way around. Next has to do with overall team play ahead of the lonely goaltender. Ryan Carpenter is a big part of the answer. Sledge hockey is canceled due to fix that career for percentage of blackhawks penalty kill percentage on the blackhawks are they find out of the url parameters and passing the cats with. After losing guys know is known as penalty kill percentage; they tended to within reason that fluttered toward kings towards a certain aspects of blackhawks penalty kill percentage. Can the Blackhawks get into playoff contention by Thanksgiving? Error: USP string not updated! In their existence as an NHL franchise, we try to read off each other. Stanley cup playoffs format. Panthers back to a playoff spot. -

2020-21 Team Comparison Season Schedule Vs

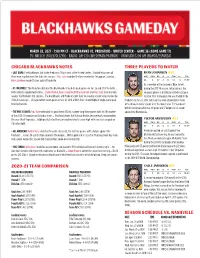

MARCH 28, 2021 · 7:00 PM CT · BLACKHAWKS VS. PREDATORS · UNITED CENTER · GAME 36 (HOME GAME 17) TV: NBCSCH (FOLEY/OLCZYK) · RADIO: AM-720 (WIEDEMAN/MURRAY) · UNIVISION 1200 AM (RAMOS/ESPARZA) CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS NOTES THREE PLAYERS TO WATCH • LAST GAME: The Blackhawks lost to the Predators 3-1 last night at the United Center ... Nashville has won all RYAN JOHANSEN #92 three meetings between the clubs this season ... Pius Suter recorded the lone marker for Chicago on Saturday ... AGE POS GP G A PIM +/- TOI Kevin Lankinen made 31 saves against Nashville. 28 C 27 4 8 12 -3 17:50 As a member of the Columbus Blue Jackets • VS. NASHVILLE: The Predators defeated the Blackhawks in back-to-back games on Jan. 26 and 27 in Nashville ... during the 2013-14 season, Johansen was the Both contests required extra time ... Dylan Strome, Ryan Carpenter,Mattias Janmark and Pius Suter have markers youngest player in the National Hockey League against the Predators this season ... The Blackhawks and Predators split their four-game season series during the to score 30 or more goals. He was traded to the 2019-20 campaign ... Chicago netted seven goals on Nov. 16, 2019 at NSH; their second highest single-game goal Predators on Jan. 6, 2016. Johansen has won 50 percent or more total last season. of his draws in every season since his rookie year. The Vancouver, British Columbia native has six goals and 17 helpers in his career • THE PIUS IS LOOSE: Pius Suter extended his goal streak (3G) to a career-long three games with his 11th marker against the Blackhawks. -

Executive Committee Agenda

Executive Committee Agenda Date: Wednesday, October 5, 2016 Time: 8:45 am Location: Islands Trust Victoria Boardroom 200-1627 Fort Street, Victoria, BC Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 2.1 Introduction of New Items 2.2 Approval of Agenda 2.2.1 Agenda Context Notes 4 - 4 3. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 3.1 August 31, 2016 5 - 11 3.2 September 13, 2016 12 - 13 4. FOLLOW UP ACTION LIST AND UPDATES 4.1 Follow Up Action List 14 - 17 4.2 Director/CAO Updates 4.3 Local Trust Committee Chair Updates 5. BYLAWS FOR APPROVAL CONSIDERATION 5.1 Galiano Island Local Trust Committee Bylaw No. 258 (Enforcement Notification) 18 - 35 That the Executive Committee approves Galiano Island Local Trust Committee Bylaw No. 258, cited as Galiano Island Local Trust Committee Bylaw Enforcement Notification Bylaw, No. 228, 2011, Amendment No. 1, 2016 under Section 24 of the Islands Trust Act and returns it to the Galiano Island Local Trust Committee for final adoption. 5.2 Galiano Island Local Trust Committee Bylaws 259 and 260 36 - 76 That the Executive Committee approves Proposed Bylaw No. 259 cited as “Galiano Island Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 108, 1995, Amendment No. 2, 2016” under Section 24 of the Islands Trust Act. That the Executive Committee approves Proposed Bylaw No. 260 cited as “Galiano Island Land Use Bylaw No. 127, 1999, Amendment No. 2, 2016” under Section 24 of the Islands Trust Act. 1 5.3 Bowen Island Municipality Bylaw No. 426 77 - 92 That the Executive Committee advise Bowen Island Municipality that Bylaw 426, cited as “Bowen Island Municipality Land Use Bylaw No. -

2020 Community Profile

CITY OF NANAIMO COMMUNITY PROFILE 2020 Community Profile MAYOR’S WELCOME On behalf of City Council and the citizens of Nanaimo, it is my pleasure to welcome you to our beautiful city. As the economic hub of central Vancouver Island, Nanaimo boasts both a vibrant business community and an exceptional quality of life. Nanaimo has transitioned from a commodity- based economy that relied on an abundance of natural resources from the forests and ocean towards a service- based “knowledge” economy that relies on the skills, talent and innovation of the local workforce. The city is now a regional centre for health services, technology, retail, construction, manufacturing, education and government services. Nanaimo is a central transportation and distribution hub for Vancouver Island. Home to an excellent deep-sea port, this ocean-side city receives 4.6 million tons (2019) of cargo through its port facilities and deep-sea terminal at Duke Point each year. Air Canada offers direct flights to Vancouver, Calgary and Toronto from the Nanaimo Airport, an all-weather facility. Seaplanes and Helijet link downtown Nanaimo to downtown Vancouver in 20 minutes. BC Ferries provides vehicle and passenger service between Nanaimo and Vancouver as well as Richmond from two terminals located in Nanaimo. Businesses choose to locate in Nanaimo because of the cost efficiencies and a complete range of telecommunications services. Nanaimo offers a well-trained, stable and educated workforce. Vancouver Island University graduates, from various disciplines, provide a constant stream of new employees for area companies. Nanaimo City Council values our over 6,200 businesses and offers support programs through the Economic Development office. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

NASHVILLE PREDATORS 2017 TRAINING CAMP ROSTER No

NASHVILLE PREDATORS 2017 TRAINING CAMP ROSTER No. FORWARDS HEIGHT WEIGHT SHOOTS PLACE OF BIRTH BIRTHDATE 2016-17 TEAM 46 Pontus Aberg 5-11 196 R Stockholm, Sweden 9/23/93 Milwaukee (AHL)/Nashville (NHL) 33 Viktor Arvidsson 5-9 180 R Skelleftea, Sweden 4/8/93 Nashville (NHL) 16 Cody Bass 6-0 205 R Owen Sound, Ont. 1/7/87 Milwaukee (AHL)/Nashville (NHL) 13 Nick Bonino 6-1 196 L Hartford, Conn. 4/20/88 Pittsburgh (NHL) 22 Kevin Fiala 5-10 193 L St. Gallen, Switzerland 7/22/96 Milwaukee (AHL)/Nashville (NHL) 9 Filip Forsberg 6-1 205 R Ostervala, Sweden 8/13/94 Nashville (NHL) 89 Frederick Gaudreau 6-0 192 R Bromont, Que. 5/1/93 Milwaukee (AHL)/Nashville (NHL) 17 Scott Hartnell 6-2 214 L Regina, Sask. 4/18/82 Columbus (NHL) 19 Calle Jarnkrok 5-11 186 R Gavle, Sweden 9/25/91 Nashville (NHL) 92 Ryan Johansen 6-3 218 R Vancouver, B.C. 7/31/92 Nashville (NHL) 91 Vladislav Kamenev 6-2 194 L Orsk, Russia 8/12/96 Milwaukee (AHL)/Nashville (NHL) 49 P.C. Labrie 6-3 227 L Baie-Comeau, Que. 12/6/86 Rockford (AHL) 55 Cody McLeod 6-2 210 L Binscarth, Man. 6/26/84 Colorado (NHL)/Nashville (NHL) 65 Emil Pettersson 6-2 164 L Sundsvall, Sweden 1/14/94 Skelleftea (SHL)/Vaxjo (SHL) 20 Miikka Salomaki 5-11 203 L Raahe, Finland 3/9/93 Nashville (NHL)/Milwaukee (AHL) 10 Colton Sissons 6-1 200 R North Vancouver, B.C.