The Standard History of the War Vol. I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAT Karine Guérand Janvier 2006 .PMD

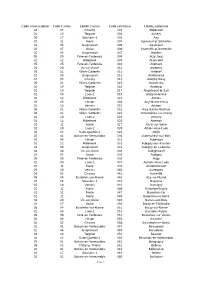

1 2 Préambule 3 Document élaboré à la demande des élus, par la Direction de l'Eau et de l'Environnement du Conseil Général de Seine et Marne avec le concoursde l'Agence de l'Eau Seine Normandie (en particulier le rapport de stage de David NGUYEN-THE- septembre 1999), de la Direction Départementale de l'Agriculture et de la Forêt de la Marne, des Missions Interservices de l'Eau de l'Aisne et de la Seine et Marne, et de la Direction Régionale de l'Environnement d'Ile de France. SITUATION ET TERRITOIRE ❚ Le Grand Morin et le Petit Morin sont deux affluents de la Marne. Ils sont situés dans la partie aval de celle-ci. Leurs confluences avec la Marne se trouvent pour ➧ le Grand Morin à Condé-Sainte-Libiaire et Esbly ➧ le Petit Morin à La Ferté-sous-Jouarre Ces deux confluences sont distantes d’une vingtaine de kilomètres. ❚ Les bassins versants des deux Morins sont mitoyens et se situent dans ➧ la Brie ➧ la Champagne ❚ Ils recouvrent trois régions administratives 4 ➧ la Picardie ➧ la Champagne-Ardennes ➧ l’Ile-de-France chacune étant représentée par un département ➧ l’Aisne ➧ la Marne ➧ la Seine-et-Marne ❚ Situation générale du bassin versant des deux Morins ❚ Répartition des communes appartenant au moins en partie, au bassin versant de l’un ou l’autre des Morins ➧ 7 dans l’Aisne ➧ 71 dans la Marne ➧ 105 dans la Seine et Marne soit 183 communes. La répartition de celles-ci entre les deux bassins versants est d'environ ➧ 1/3 pour le Petit Morin ➧ 2/3 pour le Grand Morin Limite du bassin versant ❚ Zoom sur le bassin versant des deux Morins LISTE -

Rapport D'activités 2018 16889.74 Ko |

RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉS & de gestion 2018 CONNAÎTRE PROTÉGER GÉRER VALORISER ACCOMPAGNER Vous avez entre les mains le rapport d’activités 2018 du Conservatoire d’espaces naturels de Picardie. Sans être exhaustif il présente les principales actions menées en 2018 par le Conservatoire d’espaces naturels de Picardie selon les axes structurants de notre plan d’actions quinquennal : connaître, protéger, gérer, valoriser, accompagner les politiques publiques de préservation de la nature, participer et contribuer aux dynamiques de réseaux permettant de démultiplier nos actions régionales. Bien sûr, s’ajoutent ici des informations générales et synthétiques sur la situation du Conservatoire : bilan chiffré et cartographique de la maîtrise foncière et d’usage, bilan moral, bilan financier, fonctionnement de la structure. Sur ce dernier point un accent particulier est mis sur la poursuite de nos travaux de rapprochement avec le Conservatoire Nord Pas-de-Calais. Nous espérons que sa lecture vous sera tout aussi informative qu’attrayante. Sommaire Bilan moral........................................................................................................p. 3 2018 en chiffres................................................................................................p. 5 Évolution du nombre de sites et de la surface d’intervention................p. 6 Le Conservatoire en Picardie ........................................................................p. 8 Tableau des sites............................................................................................p. -

Aubetin De Sa Source Au Confluent Du Grand Morin (Exclu)

FRHR151 L'Aubetin de sa source au confluent du Grand Morin (exclu) Référence carte 2514 Ouest; 2515 Ouest; Statut: naturelle Objectif global et Bon état IGN: 2615 Est; 2615 Ouest délai d'atteinte : 2027 Distance à la source : 0 Etat chimique actuel avec HAP: non atteinte du bon état Longeur cours principal: 61,9 Etat écologique actuel avec polluants spécifiques : état moyen (km) * la description des affluents de la masse d'eau figure en annexe IDENTIFICATION DE LA MASSE D'EAU Petite masse d'eau associée : FRHR151‐F656300 ru de volmerot FRHR151‐F656900 ru de chevru FRHR151‐F657400 ru de maclin FRHR151‐F656200 ru de l' etang L'Aubetin prend sa source sur la commune de Bouchy‐Saint‐Genest (51) puis entre en Seine et Marne après un parcours de quelques kilomètres et s'y écoule sur près de 50 km avant de confluer en rive gauche du Grand Morin, à Pommeuse. Il reçoit le long de son cours, les eaux de plusieurs affluents, principalement en rive droite : le ru de Turenne, les rus de Volmerot, Saint‐Géroche, de Chevru, Baguette, Maclin, Loef, et enfin l’Oursine. Les affluents en rive gauche drainent de faibles bassins versants boisés qui ravinent lors de fortes pluies. La rivière coule sur des alluvions reposant sur les calcaires de Champigny dans lesquelles s'infiltrent une partie des eaux superficielles. Les relations entre la nappe du Champigny et les eaux superficielles de l'Aubetin sont complexes et variables selon le niveau de la nappe. Voir cartes n° 1 et 2 de l'atlas départemental pour la localisation de la masse d'eau et les objectifs et délais DCE 1. -

Ualité De L'eau Distribuée À MAUPERTHUIS

- ualité de l’eau distribuée à MAUPERTHUIS n° 281 Synthèse de l’année 2012 EAU D ’EXCELLENTE QUALITE BACTERIOLOGIQUE BACTERIOLOGIE Origine de l'eau Micro -organismes indicateurs Tous les prélèvements sont conformes. Eau souterraine provenant d’un d’une éventuelle contamination puits et d’un forage situés à des eaux par des bactéries Dagny et en appoint, de quatre pathogènes. Absence exigée. forages situés à Amillis et Beautheil. Ces ouvrages captent les nappes des calcaires de NITRATES EAU CONFORME A LA LIMITE DE QUALITE , CONTENANT PEU DE Champigny et de Saint-Ouen. La NITRATES gestion est assurée par le Syndicat Nord Est. Eléments provenant principalement de l’agriculture, Moyenne : 18,4 mg/l Maximum : 23 mg/l des rejets domestiques et industriels. La teneur ne doit pas excéder 50 milligrammes par litre. Contrôles sanitaires réglementaires DURETE EAU CALCAIRE La Délégation Territoriale de Une eau calcaire n’a aucune incidence sur la santé Seine et Marne est chargée du contrôle sanitaire de l’eau Teneur en calcium et en Moyenne : 31 °F Maximum : 38 °F magnésium dans l’eau. Il n’y a pas potable. Cette synthèse prend en compte les résultats des 30 de valeur limite réglementaire de échantillons prélevés en dureté. productio n et des 48 échantillons prélevés en distribution. FLUOR EAU CONFORME A LA LIMITE DE QUALITE , TRES PEU FLUOREE Oligo -éléments présents Moyenne : 0,28 mg/l Maximum : 0,4 mg/l naturellement dans l’eau. La Le fluor a un rôle efficace pour prévenir l’apparition des caries. Conseils teneur ne doit pas excéder 1,5 milligrammes par litre. -

American Armies and Battlefields in Europe 533

Chapter xv MISCELLANEOUS HE American Battle Monuments The size or type of the map illustrating Commission was created by Con- any particular operation in no way indi- Tgress in 1923. In carrying out its cates the importance of the operation; task of commeroorating the services of the clearness was the only governing factor. American forces in Europe during the The 1, 200,000 maps at the ends of W or ld W ar the Commission erected a ppro- Chapters II, III, IV and V have been priate memorials abroad, improved the placed there with the idea that while the eight military cemeteries there and in this tourist is reading the text or following the volume records the vital part American tour of a chapter he will keep the map at soldiers and sailors played in bringing the the end unfolded, available for reference. war to an early and successful conclusion. As a general rule, only the locations of Ail dates which appear in this book are headquarters of corps and divisions from inclusive. For instance, when a period which active operations were directed is stated as November 7-9 it includes more than three days are mentioned in ail three days, i. e., November 7, 8 and 9. the text. Those who desire more com- The date giYen for the relief in the plete information on the subject can find front Jine of one division by another is it in the two volumes published officially that when the command of the sector by the Historical Section, Army W ar passed to the division entering the line. -

Arrêté Préfectoral N° 2015/DDT/SEPR/137 Définissant

PREFET DE SEINE-ET-MARNE Direction départementale des territoires Service environnement et prévention des risques Arrêté préfectoral n° 2015/DDT/SEPR/137 définissant les seuils entraînant des mesures de limitation provisoire des usages de l'eau et de surveillance sur les rivières et les aquifères de Seine-et-Marne Le Préfet de Seine-et-Marne Officier de la Légion d’honneur, Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite, VU le code de l’environnement et notamment ses articles L.210-1, L.211-3, L.214-7, L.214-18, L.215-10 R.211-66 à R.211-70, R212-1 à 2, R.213-14 à R.213-16 et R.216-9 ; VU le code de la santé publique ; VU le décret du Président de la République en date du 31 juillet 2014 portant nomination de Monsieur Jean-Luc MARX, préfet de Seine-et-Marne (hors classe); VU l’arrêté du Premier Ministre en date du 14 juin 2013 nommant Monsieur Yves SCHENFEIGEL, directeur départemental des territoires de Seine-et-Marne ; VU l’arrêté préfectoral n°14/PCAD/92 du 01 septembre 2014 donnant délégation de signatures à Monsieur Yves SCHENFEIGEL, administrateur civil hors classe, directeur départemental des territoires de Seine-et-Marne ; VU le décret n° 2004-374 du 29 avril 2004, relatif aux pouvoirs des préfets, à l'organisation et à l’action des services de l’État dans les régions et départements ; VU l’arrêté n°2009-1531 du 20 novembre 2009 approuvant le Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux du Bassin Seine-Normandie ; VU l’arrêté n°2015 103-0014 du 13 avril 2015 du Préfet de la région Île-de-France, Préfet de Paris, Préfet coordonnateur du bassin Seine-Normandie, préconisant des mesures coordonnées de gestion de l’eau sur le réseau hydrographique du bassin Seine-Normandie en période de sécheresse et définissant des seuils sur certaines rivières du bassin entraînant des mesures coordonnées de limitation provisoire des usages de l’eau et de surveillance sur ces rivières et leur nappe d’accompagnement. -

ZRR - Zone De Revitalisation Rurale : Exonération De Cotisations Sociales

ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales URSSAF Présentation du dispositif Les entreprises en ZRR (Zone de Revitalisation Rurale) peuvent être exonérée des charges patronales lors de l'embauche d'un salarié, sous certaines conditions. Ces conditions sont notamment liées à son effectif, au type de contrat et à son activité. Conditions d'attribution A qui s’adresse le dispositif ? Entreprises éligibles Toute entreprise peut bénéficier d'une exonération de cotisations sociales si elle respecte les conditions suivantes : elle exerce une activité industrielle, commerciale, artisanale, agricole ou libérale, elle a au moins 1 établissement situé en zone de revitalisation rurale (ZRR), elle a 50 salariés maximum. Critères d’éligibilité L'entreprise doit être à jour de ses obligations vis-à-vis de l'Urssaf. L'employeur ne doit pas avoir effectué de licenciement économique durant les 12 mois précédant l'embauche. Pour quel projet ? Dépenses concernées L'exonération de charges patronales porte sur le salarié, à temps plein ou à temps partiel : en CDI, ou en CDD de 12 mois minimum. L'exonération porte sur les assurances sociales : maladie-maternité, invalidité, décès, assurance vieillesse, allocations familiales. URSSAF ZRR - Zone de Revitalisation Rurale : exonération de cotisations sociales Page 1 sur 5 Quelles sont les particularités ? Entreprises inéligibles L'exonération ne concerne pas les particuliers employeurs. Dépenses inéligibles L'exonération de charges ne concerne pas les contrats suivants : CDD qui remplace un salarié absent (ou dont le contrat de travail est suspendu), renouvellement d'un CDD, apprentissage ou contrat de professionnalisation, gérant ou PDG d'une société, employé de maison. -

1779 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Kyllonen

1779 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Kyllonen pation, farmer; inducted at Hillsboro on April 29, 1918; sent to Camp Dodge, Iowa; served in Company K, 350th Infantry, to May 16, 1918; Com- pany K, 358th Infantry, to discharge; overseas from June 20, 1918, to June 7, 1919. Engagements: Offensives: St. Mihiel; Meuse-Argonne. De- fensive Sectors: Puvenelle and Villers-en-Haye (Lorraine). Discharged at Camp Dodge, Idwa, on June 14, 1919, as a Private. KYLLONEN, CHARLEY. Army number 4,414,704; registrant, Nelson county; born, Brocket, N. Dak., July 5, 1894, of Finnish parents; occu- pation, farmer; inducted at La,kota on Sept. 3, 1918; sent to Camp Grant, Ill.; served in Machine Gun Training Center, Camp Hancock, Ga., to dis- charge. Discharged at Camp Hancock, Ga., on March 26, 1919, as a Private. KYLMALA, AUGUST. Army number 2,110,746; registrant, Dickey county; born, Oula, Finland, Aug. 9, 1887; naturalized citizen; occupation, laborer; inducted at Ellendale on Sept. 21, 1917; sent. to Camp Dodge, Iowa; served in Company I, 352nd Infantry, to Nov. 28, 1917; Company L, 348th Infantry, to May 18, 1918; 162nd Depot Brigade, to June 17, 1918; 21st Battalion, M. S. Gas Company, to Aug. 2, 1918; 165th Depot Brigade, to discharge. Discharged at Camp Travis, Texas, on Dec. 4, 1918, as a Private. KYNCL, JOHN. Army number 298,290; registrant, Cavalier county; born, Langdon, N. Dak., March 27, 1896, of Bohemian parents; occupation, farmer; inducted at Langdon on Dec. 30, 1917; sent to Fort Stevens, Ore.; served in Battery D, 65th Artillery, Coast Artillery Corps, to discharge; overseas from March 25, 1918, to Jan. -

COMPTE RENDU Du CONSEIL MUNICIPAL Du 12 Juin 2017

COMPTE RENDU du CONSEIL MUNICIPAL du 12 juin 2017 L’an deux mil dix-sept, lundi 12 juin, 18 heures 30, le Conseil Municipal de la commune de MISSY sur AISNE, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni en session ordinaire, en séance publique, à la Mairie, sous la présidence de M. Claude MADIOT, Maire. Date de la convocation : 2 juin 2017. Présents : Didier AOSMAN, I. BROIGNIEZ, M.G. CHARPENTIER, J.B COUPY, Dominique LECOMTE, Corinne LEDOUX, Jean-Pierre MARTINIE, Richard MOREAU, Christophe POTIER, E. QUENNESSON, et Martin WIBAUX. Absents excusés avec pouvoir : Mme Sandrine SANTINI et M. Jean-Pierre HECQUET Madame Sandrine SANTINI donne pouvoir à Mme M.G. CHARPENTIER, adjointe au Maire. Monsieur Jean-Pierre HECQUET donne pouvoir à J.B COUPY, conseiller Absente excusée : Mme M. PINTO Madame M.G. CHARPENTIER a été élue secrétaire. {{{{{{{{{{{{{{ Monsieur le Maire demande au Conseil Municipal que soient ajoutés à l'ordre du jour 4 points - la demande de FDS 2017 - la mise en place des nouveaux transports scolaires avec ou sans prise en charge du montant de la carte scolaire, frais d'inscription, avenant à la régie d'avance. Le Conseil Municipal accepte l'ajout de ces 4 points - Adoption du procès verbal de la dernière réunion Après lecture, le procès verbal de la réunion du 27 mars 2017 est approuvé à l’unanimité. I. – CCVA modification des statuts art. 2 (D/2017-24) Le 29 septembre 2016, la CCVA a adopté de nouveaux statuts et les a soumis à l’approbation des communes. Le libellé des statuts ne respectant pas strictement celui prévu par l’article L5214-16 du Code général des collectivités territoriales, les services du contrôle de la légalité ont demandé à la CCVA de réécrire les statuts. -

DRAC Picardie « CRMH » Liste Des Édifices Protégés Triés Par Commune

DRAC Picardie « CRMH » Liste des édifices protégés triés par commune Département : 02 - Aisne Type : immeuble Commune Unité de patrimoine Protection Etendue de la protection Adresse Agnicourt-et- Eglise classement Eglise : classement par arrêté du 12 août 1921 Séchelles 12/08/1921 Aisonville-et- Château de Bernoville inscription Façades et toitures du château et des pavillons (B3, 181), grille Bernoville Bernoville, 02110 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 24/12/1997 d'entrée ( B3, 181), allée d'honneur (B3) et jardin à la française (B3, 182). Aizy-Jouy Creute du Caïd classement Paroi aux motifs de la Creute du Caïd. 02370 AIZY-JOUY 27/09/1999 Aizy-Jouy Eglise (ancienne) classement et par arrêté du 21 août 1927 Ambleny Donjon classement Donjon : classement par décret du 24 février 1929 24/02/1929 Ambleny Eglise classement Eglise : classement par arrêté du 27 juillet 1907 27/07/1907 Ancienville Croix inscription Croix, sur le bord de la route près de l'église : inscription par 15/06/1927 arrêté du 15 juin 1927 Andelain Eglise classement Eglise : classement par arrêté du 12 août 1921 12/08/1921 Archon Eglise inscription Deux tours de défense de la façade occidentale : inscription par 03/06/1932 arrêté du 3 juin 1932 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue Château de Branges (ancien) inscription Parties du 16e siècle comprenant la tourelle, la porte charretière 08/02/1928 et la petite porte armoriée : inscription par arrêté du 8 février 1928 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue Eglise classement Eglise : classement par arrêté du 10 janvier 1920 10/01/1920 Armentières-sur- Ponts Bernard -

1003 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Furuseth

1003 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Furuseth FURUSETH, OSCAR CARL. Army number 863,233; registrant, Moun- trail county; born, Halstad, Minn., March 7, 1891, of Norwegian parents; occupation, blacksmith; enlisted at Fort Snelling, Minn., on Dec. 15, 1917; sent to Vancouver Barracks, Wash.; served in 407th Aero Construction Squadron, Air Service, Signal Corps, to Feb. 1, 1918; 404th Aero Construc- tion Squadron, to July 4, 1918; 31st Provisional Squadron, to Jan. 21, 1919; 27th Spruce Squadron, 2nd Provisional Regiment, to discharge. Grade: Sergeant, Feb. 8, 1918. Discharged at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on Jan. 31, 1919, as a Sergeant. FUSKERUD. ALBERT. Navy number 1,518,819; registrant, LaMoure county; born, Nunda, S. Dak., March 29, 1890, of Norwegian-American parents; occupation, farmer; enlisted in the Navy at Aberdeen, S. Dak, on Dec. 4, 1917; served at Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Ill., to April 18, 1918; USS Leviathan, to Nov. 11, 1918; Grades: Apprentice Sea- man, 59 days; Seaman 2nd Class, 120 days; Fireman 3rd Class, 137 days; Fireman 2nd Class, 26 days. Discharged at Hoboken, N. J., on Oct. 29, 1919, as a Fireman 1st Class. FUSSELL, EDWIN BRIGGS. Army number 467,712; registrant, Cass county; born, Washington, D. C., Oct. 4, 1886, of (nationality of parents not given); occupation, reporter; inducted at Fargo on March 6, 1918; served in Training School, Ordnance Field Service, University of Cali- fornia, to April 27, 1918; SuPply School, Ordnance Training Camp, Camp Hancock, Ga., to July 2, 1918; Ordnance Detachment, Ordnance Depot Company No. 123, to discharge. Grade: Private 1st Class, July 10, 1918. -

Code Circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code Commune

Code circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code commune Libellé_commune 04 03 Chauny 001 Abbécourt 01 18 Tergnier 002 Achery 05 17 Soissons-2 003 Acy 03 11 Marle 004 Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 01 06 Guignicourt 005 Aguilcourt 03 07 Guise 006 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 01 06 Guignicourt 007 Aizelles 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 008 Aizy-Jouy 02 12 Ribemont 009 Alaincourt 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 010 Allemant 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 011 Ambleny 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 012 Ambrief 01 06 Guignicourt 013 Amifontaine 04 03 Chauny 014 Amigny-Rouy 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 015 Ancienville 01 18 Tergnier 016 Andelain 01 18 Tergnier 017 Anguilcourt-le-Sart 01 09 Laon-1 018 Anizy-le-Grand 02 12 Ribemont 019 Annois 03 08 Hirson 020 Any-Martin-Rieux 01 19 Vervins 021 Archon 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 022 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 023 Armentières-sur-Ourcq 01 10 Laon-2 024 Arrancy 02 12 Ribemont 025 Artemps 01 11 Marle 027 Assis-sur-Serre 01 10 Laon-2 028 Athies-sous-Laon 02 13 Saint-Quentin-1 029 Attilly 02 01 Bohain-en-Vermandois 030 Aubencheul-aux-Bois 03 08 Hirson 031 Aubenton 02 12 Ribemont 032 Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes 01 06 Guignicourt 033 Aubigny-en-Laonnois 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 034 Audignicourt 03 07 Guise 035 Audigny 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 036 Augy 01 09 Laon-1 037 Aulnois-sous-Laon 03 11 Marle 039 Autremencourt 03 19 Vervins 040 Autreppes 04 03 Chauny 041 Autreville 05 04 Essômes-sur-Marne 042 Azy-sur-Marne 04 16 Soissons-1 043 Bagneux 03 19 Vervins 044 Bancigny 01 11 Marle 046 Barenton-Bugny 01 11 Marle 047 Barenton-Cel 01 11 Marle 048 Barenton-sur-Serre