Imbecile” Institution and the Limits of Public Engagement: Art Museums and Structural Barriers to Public Value Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARSV15N1A5.Pdf (1.183Mb)

Mid-American Review of Sociology GENDER AND EVALUATION IN FINE ART. They show their evaluation of her through their own rites and meetings" (p. n). Traq' X. Karner This differs from Schur'snotion of the source of the structural ambivalence The University ofKansas present within society. While Schur implies that the devaluation of women propagates from and is supported by the behavior and perception of men, the Mid-American Review of Sociology, 1991, Vol. XV, No. 1:53-69 literature cited indicates that female gang members are influenced more by the constraints of their female peers than by the perceptions of male gang !he significance of ~en~er and its potential as a stigmatic social label members. Contrary to the literature, one could argue that because female ~n the field i!f art IS Investigated. As art objectifies both a society's gangs are most often auxiliary components to male gangs, female gang ideals and biases, the recognition and appreciation of art can be seen members are more dependant upon their male counterparts to define as a pivot~1 poi~t fro~ which to ~tudy. social values. Gender, having gender-related norms than are females in the society at large, where ~een prevlo~s/y Identified as a StlgnJDIIC label in fonnalized careers, independent female associations are more likely to occur. Nevertheless, what ts hypotheslze~ to account for tile lack oj recognized art works by seems necessary is to approach female gang delinquency and the normative women: Especially as the realm oj art has no formalized criteria for structure of the gang as it relates to both male and female peer influences, e~aluatlng competence. -

The Role of Cultural Value in the Historical Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu Tony Bennett

The Historical Universal: The Role of Cultural Value in the Historical Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu Tony Bennett The definitive version of this article is published in: Bennet, T. 2005, ‘The Historical Universal: The Role of Cultural Value in the Historical Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu’, The British Journal of Sociology, 56(1): 141-164. The definitive version of this article is published in: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00051.x/abstract (institutional or subscribed access may be required) The journal British Journal of Sociology is available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1468-4446 (institutional or subscribed access may be required) Copyright remains with the publisher, Blackwell Publishing. Disclaimer Please note that this is an electronic, pre-print version of this article produced by the Institute for Culture & Society, University of Western Sydney, in accordance with the requirements of the publisher. Whilst this version of the article incorporates refereed changes and has been accepted for publication, differences may exist between this and the final, published version. Citations should only be made from the published version. User Agreement Copyright of these pre-print articles are retained by the author. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article to facilitate their own study or non-commercial research. Wider circulation and distribution of the material and/or use of it in profit-making activities is prohibited. URLs to access this pre-print version can -

New Saskatoon Museum Remai Modern Gives a Taste of Future

New Saskatoon museum Remai Modern gives a taste of future programming in its inaugural exhibition | The Art Newspaper 11/01/2021, 12:55 New Saskatoon museum Remai Modern gives a taste of future programming in its inaugural exhibition The Modern and contemporary museum will show Canadian and international artists including General Idea, John Baldessari and Rosemarie Trockel Victoria Stapley-Brown Stan Douglas, The Secret Agent [film still] (2015) Stan Douglas, image courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/new-saskatoon-museum-remai-…-gives-a-taste-of-future-programming-in-its-inaugural-exhibition Page 1 of 4 New Saskatoon museum Remai Modern gives a taste of future programming in its inaugural exhibition | The Art Newspaper 11/01/2021, 12:55 The Remai Modern, a new Modern and contemporary art museum in Saskatoon, Canada, due to open on 21 October, has chosen to launch its programming with a museum-wide group exhibition as “a primer to indicate our programme direction going forward”, says Gregory Burke, the director and chief executive. The show, Field Guide (until 25 February 2018), which Burke co-organised with the museum’s director of programmes and chief curator, Sandra Guimarães, demonstrates some of the museum’s priorities, such as showing works by a mix of Canadian and international artists, acting as an “artist-centred” institution and being a champion for work by contemporary indigenous artists. Field Guide shows pieces from the collection (many of which come from the city’s former Mendel Art Gallery, closed in 2015), new acquisitions, site-specific commissions and loaned works by 80 artists and collectives, including John Baldessari, Kader Attia and Hito Steyerl. -

Reproductions, Cultural Capital and Museums: Aspects of the Culture of Copies

47 Reproductions, cultural capital and museums: aspects of the culture of copies Gordon Fyfe* Keele University Abstract The concept of cultural capital is well known in museum studies from pioneering visitor research conducted and reported by Pierre Bourdieu in the 1960s. This paper examines the concept in the light of the criticism that, whilst it illuminates the dynamics of cultural consumption and inequality in advanced capitalist societies, its socio-genesis is less well understood. It is argued that the historical sociology of fine art reproduction provides an opportunity to (i) enlarge our understanding of its formation and (ii) to explore the cultural character of the copy and the sociology of the body. The paper draws on Marx’s concept of primitive accumulation, on Connerton’s distinction between incorporated and inscribing practices and on Bourdieu’s distinction between three states of cultural capital. Key words: cultural capital, art reproduction, museums. Introduction The concept of cultural capital features widely in museum studies and in debates about access and social inclusion. Pierre Bourdieu’s pioneering study of visitors, conducted in the 1960s, established its relevance for the museum although the concept has had a much wider sociological application than museum studies. In The Love of Art Bourdieu considers the puzzle that although public art museums celebrate citizenship and are open to all citizens only a relatively small and privileged proportion of people pass through their doors. His solution has three parts: -

Opening Date Press Release V2 Roo V4.Indd

P h +1 306 975-7610 P.O. Box 569 r e m a i m o d e r n . o r g Saskatoon SK S7K 3L6 Canada Remai Modern, Canada’s Museum of Modern Art Announces October 2017 Opening Inaugural program features world’s largest collection of Picasso linocuts, artist-led projects, immersive installations, and modern and contemporary art from Canada and the world. Saskatoon, SK, Canada (June 26, 2017) – Canada’s museum of modern art, Remai Modern, will open to the public October 21, 2017 in Saskatoon. The launch aligns with the international trend of world-class museums opening in unexpected destinations. The inaugural exhibition, Field Guide, curated by Executive Director & CEO, Gregory Burke, and Director of Programs & Chief Curator, Sandra Guimarães, will animate the entire building. Selected works from the museum’s collection will be displayed in dialogue with contemporary projects, commissions and installations by international and Canadian artists. Upon opening, Remai Modern will be an artist-centred institution that raises questions, inspires discussion, and enables transformative experiences among both local and global audiences. 1 Field Guide is not a thematic exhibition but rather a series of singular positions and coherent groupings of works that introduce Remai Modern’s program philosophy and direction, providing an open framework that invites consideration of a network of issues and questions impacting art and society today. “The concept for Field Guide emerges from a set of questions we asked ourselves during the establishment of Remai Modern, including: What is modern? Can art confront reality? What is urgent and why? How will Indigeneity shape the future? And what role can be played by a new art museum opening in Saskatoon, Canada?” said Gregory Burke, Executive Director & CEO. -

THE ARTIST's PRINT AS a STRATEGY for SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT Bess Frimodig a Thesis Submitted in Partial F

AN HONOURABLE PRACTICE: THE ARTIST’S PRINT AS A STRATEGY FOR SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT Bess Frimodig A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education University of the West of England, Bristol April 2014 Volume I 0 List of Illustrations Fig.3. Fukuzoku Koto Gakko High School Year Book, Kanazawa, Japan 1980 Plate I. She Still Rules Plate II. Twente Identity Robe Plate V. Stand Up To Hatred: Wall of Resistance Plate VI. To Let Plate VII. Mapping The Longest Print 1 CONTENTS Pg.4 AUTHOR DECLARATION Pg.5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Pg.6 ABSTRACT Pg.7 INTRODUCTION Pg.8 The dilemma Pg.10 Research Question Pg.10 Aims and Objectives Pg.10 Development of the research and its rationale Pg.12 Methodology Pg.14 Outline Pg.16 CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND Pg.17 Personal Context Pg.22 The Social Role of Art – A Debate Pg.27 Why print? Pg.27 History of Print Pg.35 Literature of Print – Texts, Websites and Blogs Pg.49 The Way Forward: The Individual Artist and Entering the Collective Pg.49 Models of practice Pg.58 Guiding principles Pg.59 CHAPTER TWO: CASE STUDIES Pg.60 CS1 Black History Month Pg.61 Introduction Pg.61 Aims and Objectives Pg.62 Context Pg.62 The Print Pg.63 Evaluation Pg.66 Conclusion Pg.67 The Way Forward Pg.68 CS2 AKI Twente Identity Robe Pg.69 Introduction Pg.69 Aims and Objectives Pg.70 Context Pg.70 The Print Pg.73 Evaluation Pg.74 Conclusion Pg.75 The Way Forward Pg.76 CS3 Stand up to Hatred: Wall of Resistance -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

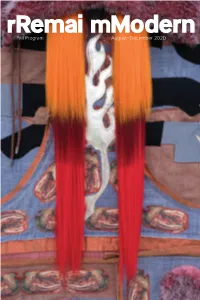

Fall Program August–December 2020 Welcome Back Ensuring a Safe and Healthy Return to Remai Modern for All Visitors and Staff Is Our Top Priority

Fall Program August–December 2020 Welcome back Ensuring a safe and healthy return to Remai Modern for all visitors and staff is our top priority. Visits to the museum promise to be as inspiring as ever, but there are a few new visitor guidelines to be aware of. We ask for your cooperation and patience as we institute new measures aimed at keeping everyone protected. Online tickets Visitors are encouraged to purchase their admission tickets in advance to limit contact during their visit. Members enjoy unlimited admission and do not need to pre-register their visit. Admission will be first-come, first-served to ensure new capacity guidelines aren’t exceeded. Adjusted hours At reopening, the museum will be open Thursday to Sunday from 10 AM–5 PM. Please visit remaimodern.org for updates. Increased sanitation Frequency of cleaning has been increased throughout the building, particularly in high traffic areas. Additionally, hand sanitization stations have been added at the front entrance and on each level of the museum. New signage Signage throughout the building will indicate maximum number of people in designated spaces, traffic flow and other important changes. Please follow these signs during your visit. Masks Visitors are strongly encouraged to wear a face covering while at Remai Modern. Distancing Visitors are asked to practice physical distancing in all museum spaces. Please remain two metres away from all guests who aren’t part of your household. Please follow guidelines posted throughout Remai Modern. Visit remaimodern.org/plan-your-visit for the latest information. Front cover: Zadie Xa, The Re-Up of Yung Yoomi: Hell Fire Can’t Scorch Me (detail), 2018, hand-sewn and machine-stitched assorted fabrics, faux fur and synthetic hair on bamboo, 188 cm x 210 cm. -

View the Gallery Branch Art Collection

THE COLLECTION AT CIBC WOOD GUNDY GALLERY BRANCH CIBC World Markets Inc. 200 King Street West, Suite 1807 Toronto ON M5H 3T4 PHOTOGRAPHY: Robert Burley ARCHITECT: Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg MAIN RECEPTION WORKS BY JOHN MASSEY JOHN MASSEY LOCATION — Reception The Jack Photographs #35 – 40 1992-95 6 silver gelatin prints edition 2/5 24 x 23 inches each shown: photos 38, 39 PHOTOS Courtesy of the Artist The inevitability of technology to maim the senses and privilege vision as the dominant sense preceptor at the expense of all others is here poignantly expressed. For Massey, the computer is also the puppet. It is not just the mannequin but the computer as well that represents an agent external to the self that may enact our wishes. Massey’s interrelated images of flesh and wood, sensory organs and mechanical joints in The Jack Photographs suggest to the viewer that the body is the site of perception and memory,not just the mind alone. For Massey, the notion of watching or looking at something is also an exercise in self-perception and forms another meaningful ellipsis to The Jack Photographs.The question of self-perception, how the tools of observation intercede, and how the mind works its anxious response, its motivations, and its insights are each puzzling experiences and difficult to explain but perhaps, in electronic art, possible.The visual codes Massey embeds in this artwork are an encryption that underscores the effects of working with photography in combination with other media. Jack is the foil through which the artist engages perception as subject, identity or self-awareness as object, and the structure of vision as content. -

UAAC Conference.Pdf

Friday Session 1 : Room uaac-aauc1 : KC 103 2017 Conference of the Universities Art Association of Canada Congrès 2017 de l’Association d’art des universités du Canada October 12–15 octobre, 2017 Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity uaac-aauc.com UAAC - AAUC Conference 2017 October 12-15, 2017 Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity 1 Welcome to the conference The experience of conference-going is one of being in the moment: for a few days, we forget the quotidian pressures that crowd our lives, giving ourselves over to the thrill of being with people who share our passions and vocations. And having Banff as the setting just heightens the delight: in the most astonishingly picturesque way possible, it makes the separation from everyday life both figurative and literal. Incredibly, the members of the Universities Art Association of Canada have been getting together like this for five decades—2017 is the fifteenth anniversary of the first UAAC conference, held at Queen’s University and organized around the theme of “The Arts and the University.” So it’s fitting that we should reflect on what’s happened in that time: to the arts, to universities, to our geographical, political and cultural contexts. Certainly David Garneau’s keynote presentation, “Indian Agents: Indigenous Artists as Non-State Actors,” will provide a crucial opportunity for that, but there will be other occasions as well and I hope you will find the experience productive and invigorating. I want to thank the organizers for their hard work in bringing this conference together. Thanks also to the programming committee for their great work with the difficult task of reviewing session proposals. -

Queer Spellings: Magic and Melancholy in Fantasy-Fiction

QUEER SPELLINGS: MAGIC AND MELANCHOLY IN FANTASY-FICTION Jes Battis B.A., University College of the Fraser Valley, 2001 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department English O Jes Battis 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Jes Battis Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Research Project: Queer Spellings: Magic and Melancholy in Fantasy-Fiction Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Margaret Linley Assistant Professor of English Dr. Peter Dickinson Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor of English Dr. Helen Hok-Sze Leung Supervisor Assistant Professor of Women's Studies Dr. Dana Symons Supervisor Assistant Professor of English Dr. Ann Travers Internal Examiner Assistant Professor of Sociology Dr. Veronica Hollinger External Examiner Professor of Cultural Studies, Trent University Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

PDF Version of Contemporary Indigenous Arts

CONTEMPORARY INDIGENOUS ARTS IN THE CLASSROOM OTTAWA ART GALLERY Edited by Stephanie Nadeau and Doug Dumais Texts by David Garneau and Wahsontiio Cross Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Contemporary indigenous arts in the classroom / edited by Stephanie Nadeau and Doug Dumais ; texts by David Garneau and Wahsontiio Cross = L’art autochtone contemporain en salle de classe / sous la direction de Stephanie Nadeau et Doug Dumais ; textes par David Garneau et Wahsontiio Cross. Includes bibliographical references and index. Text in English and French. ISBN 978-1-894906-55-5 (softcover) 1. Native art--Canada--Study and teaching. 2. Koebel, Jaime--Criticism and interpretation. 3. Ace, Barry, 1958- --Criticism and interpretation. I. Nadeau, Stephanie, 1980-, editor II. Dumais, Doug, editor III. Garneau, David, 1962-, writer of added commentary IV. Cross, Wahsontiio, 1983-, writer of added commentary V. Ottawa Art Gallery, issuing body VI. Title: Art autochtone contemporain en salle de classe. VII. Title: Contemporary indigenous arts in the classroom. VIII. Title: Contemporary indigenous arts in the classroom. French. N6549.5.A54C665 2018 704.03’97071 C2018-904800-XE © 2018 Ottawa Art Gallery Cover: Barry Ace, Anishinabek in the Hood, 2007, acrylic on vinyl screen, 147.3 x 127cm, Collection of Ottawa Art Gallery. All rights reserved regarding the use of any images in this book. Textual content, including all essays, lesson plans and resource material, is licensed under Creative Commons “Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International” (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). For the license agreement, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode, and a summary (not a substitute) see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.