Barricade Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tony-Award-Winning Creators of Les Misérables and Miss Saigon

Report on the January-February 2017 University of Virginia Events around Les Misérables Organized by Professor Emeritus Marva Barnett Thanks to the generous grant from the Arts Endowment, supported by the Provost’s Office Course Enhancement Grant connected to my University Seminar, Les Misérables Today, the University of Virginia hosted several unique events, including the world’s first exhibit devoted to caricatures and cartoons about Victor Hugo’s epic novel and the second UVA artistic residency with the award-winning creators of the world’s longest-running musical—artists who have participated in no other artistic residencies. These events will live on through the internet, including the online presence of the Les Misérables Just for Laughs scholarly catalogue and the video of the February 23 conversation with Boublil and Schönberg. Les Misérables Just for Laughs / Les Misérables Pour Rire Exhibit in the Rotunda Upper West Oval Room, Jan. 21-Feb. 28 Before it was made into over fifty films and an award-winning musical, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was a rampant best seller when it appeared in 1862. The popular cartoonists who had caricatured Hugo for thirty years leapt at the chance to satirize his epic novel. With my assistance and that of Emily Umansky (CLAS/Batten ’17), French Hugo specialist Gérard Pouchain mounted the first-ever exhibit of original publications of Les Misérables caricatures— ranging from parodies to comic sketches of the author with his characters. On January 23, at 4:00 p.m. he gave his illustrated French presentation, “La caricature au service de la gloire, ou Victor Hugo raconté par le portrait-charge,” in the Rotunda Dome Room to approximately 25 UVA faculty and students, as well as Charlottesville community members associated with the Alliance Française. -

Lesher Will Hear the People Sing Contra Costa Musical Theatre Closes 53Rd Season with Epic Production

Lesher Will Hear The People Sing Contra Costa Musical Theatre Closes 53rd Season with Epic Production WALNUT CREEK, February 15, 2014 — Contra Costa Musical Theatre (CCMT) will present the epic musical “Les Miserables“at Walnut Creek’s Lesher Center for the Arts, March 21 through April 20, 2014. Tickets for “Les Miserables” range from $45 to $54 (with discounts available for seniors, youth, and groups) and are on sale now at the Lesher Center for the Arts Ticket Office, 1601 Civic Drive in Walnut Creek, 925.943.SHOW (943-7469). Tickets can also be purchased online at www.lesherArtscenter.org. Based on the novel of the same name by Victor Hugo, “Les Miserables” has music by Claude-Michel Schonberg, lyrics by Alain Boublil, Jean-Marc Natel and Herbert Kretzmer and book by Schonberg, Boublil, Trevor Nunn and John Caird. The show premiered in London, where it has been running continuously since 1985, making it the longest-running musical ever in the West End. It opened on Broadway in 1987 and ran for 6,680 performances, closing in 2003, making it the fifth longest-running show on Broadway. A Broadway revival ran from 2008 through 2010. A film version of the musical opened in 2012 and was nominated for eight Academy Awards, winning three statues. “Les Miserables” won eight Tony Awards including Best Musical. Set in early 19th-century France, it follows the story of Jean Valjean, a French peasant, and his quest for redemption after serving nineteen years in jail for having stolen a loaf of bread for his sister’s starving child. -

The South African Who Wrote the English Lyrics for 'Les Miserables' Talks to Marianne Gray in London HERBERT Kretzmer Has Ve

The South African who wrote the English lyrics for ‘Les Miserables’ talks to Marianne Gray in London HERBERT Kretzmer has very little to be miserable about. Apart from living a fascinating life, which started in Kroonstad then went via Paris and New York to London, he also wrote the English lyrics for Les Miserables, the world’s longest-running musical, which is now coming out as an all-star film. For the film, he has written the lyrics for an additional song, Suddenly, which has been nominated for an Oscar as Best Original Song. We meet in his elegant townhouse in Kensington, London, to talk about the film of the musical which is based on Victor Hugo’s novel set in 19th-century France. The musical has been running worldwide for 27 years, has been seen by 60 million people and shows no signs of flagging. The film stars two Australian leading men —Russell Crowe as the relentless Inspector Javert and Hugh Jackman as the hunted ex convict Jean Valjean — and the gorgeous Anne Hathaway as the hapless Fantine, mother of Cosette, who sells her hair to raise money. Hathaway actually had her beautiful long hair shorn to the scalp during one of the movie’s possibly most emotional sequences. Kretzmer only went on set twice during the shoot. He says he is now a “spare wheel”. “Nobody wants a writer round once his work is done,” he laughs. “He’s just being a tourist.” At 87, and with an OBE (Order of the British Empire), a chevalier of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and an honorary doctorate from Rhodes University (which he dropped out of when a student), he still is totally on the ball as he chats, in a soft South African accent, about his extraordinary life. -

„Nowhere to Go but Up“? Die Gattungsmerkmale Des Musicals

„Nowhere to Go But Up“? Die Gattungsmerkmale des Musicals Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg im Promotionsfach Historische Musikwissenschaft vorgelegt von Sarah Baumhof Hamburg, 2021 Tag der Disputation: 21.1.2021 Vorsitzende der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Ivana Rentsch Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ivana Rentsch Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Huck Anmerkungen zu Begrifflichkeiten, Schreibweisen und Quellenangaben ............................................ IV 1 Einleitung .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Ziel und Titel der Dissertation .................................................................................... 1 1.2 Aktueller Forschungsstand ......................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Sekundärliteratur: Umfang und Publikationsart ..................................................... 2 1.2.2 Subjektivität und qualitative Mängel ...................................................................... 6 1.2.3 Geographische Zentrierung .................................................................................. 11 1.2.4 Fehlende Musikanalyse ........................................................................................ 13 1.2.5 Determiniertheit .................................................................................................... 15 1.3 Fragestellung und -

Consumer Alert Regarding Ticket Purchasing

CONSUMER ALERT REGARDING TICKET PURCHASING With so many high-profile and popular events coming to Wharton Center, we have found more and more patrons are being exploited by unscrupulous ticket resellers. Often our tickets are being marketed on secondary ticket websites before the operator of the website has even purchased tickets – and they are selling at prices far above the price you will pay through whartoncenter.com. Purchasing tickets to Wharton Center events through another source might result in paying too much for your tickets or paying for tickets that are invalid. If there is a problem with your tickets, you may not be able to receive help from Wharton Center’s Ticket Office as there will be no in-house record of your transaction. In addition, we are unable to contact you if there is a change in performance time, traffic notices, etc. To avoid being ensnared by unscrupulous ticket resellers: • Bookmark our website, whartoncenter.com for ticket and show information. • Sign up for our eClub to receive information directly from Wharton Center. We urge you to protect yourself by purchasing directly from the official source for Wharton Center tickets: at whartoncenter.com; by phone at 1-800-WHARTON (1-800-942-7866); or at the Auto-Owners Insurance Ticket Office at Wharton Center. IN CASE OF EMERGENCY Please observe the lighted exit signs located throughout the building and theatre(s). All patrons should note all exits, especially those closest to your seat location. Our staff and ushers are trained to assist patrons through multiple emergency situations. If you have questions regarding our safety and security procedures, please contact the house management staff at Wharton Center by calling 884-3119 or 884-3116. -

Edition 7 | 2019-2020

peace center 5 CAMERON MACKINTOSH presents BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S A musical based on the novel by VICTOR HUGO Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by HERBERT KRETZMER Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL and JEAN-MARC NATEL Additional material by JAMES FENTON Adaptation by TREVOR NUNN and JOHN CAIRD Original Orchestrations by JOHN CAMERON New Orchestrations by CHRISTOPHER JAHNKE STEPHEN METCALFE and STEPHEN BROOKER Musical Staging by MICHAEL ASHCROFT and GEOFFREY GARRATT Projections realized by FIFTY-NINE PRODUCTIONS Sound by MICK POTTER Lighting by PAULE CONSTABLE Costume Design by ANDREANE NEOFITOU and CHRISTINE ROWLAND Set and Image Design by MATT KINLEY inspired by the paintings of VICTOR HUGO Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR and JAMES POWELL For LES MISÉRABLES National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING/ GREGORY VANDER PLOEG KAITLIN SHAW, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producers NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG & TRINITY WHEELER for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designer Associate Set Designers NIC GRAY LAURA HUNT RICHARD PACHOLSKI DAVID HARRIS & CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Musical Director Musical Supervision Associate Director RICHARD BARTH BRIAN EADS STEPHEN BROOKER & JAMES MOORE COREY AGNEW A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation peace center 9 who’s who 10 peace center the cast (In order of Appearance) Jean Valjean ......................................................................................................... -

Musical Theatre: a Forum for Political Expression

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression Boyd Frank Richards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Richards, Boyd Frank, "Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/337 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT • APPROVAL -IJO J?J /" t~.s Name: -·v~ __ ~~v~--_______________ _______________________- _ J3~~~~ ____ ~~:__ d_ epartmen. ______________________ _ College: ~ *' S' '.e..' 0 t· Faculty Mentor: __ K~---j~2..9:::.C.e.--------------------------- PROJECT TITLE; _~LCQ.(__ :Jherui:~~ ___ I1 __:lQ.C1:UiLl~-- __ _ --------JI!.c. __ Pdl~'aJ___ ~J:tZ~L~ .. -_______________ _ ---------------------------------------_.------------------ I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors level undergraduate research in this :::'ed: _._________ ._____________ , Faculty !v1entor Date: _LL_ -9fL-------- Comments (Optional): Musical Theater: A Forum for Political Expression Presented by: Ashlee Ellis Boyd Richards May 5,1999 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................2 Introduction: Musical Theatre - A Forum for Political Expression .................. -

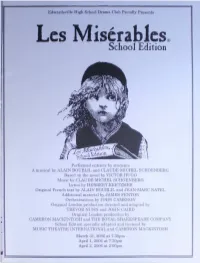

Performed Entirely by Students a Musical by ALAIN BOUBLIL And

Performed entirely by students A musical by ALAIN BOUBLIL and CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHOENBERG Based on the novel by VICTOR HUGO Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHOENBERG Lyrics by HERBERT KRETZMER Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL and JEAN-MARC NATEL Additional material by JAMES FENTON Orchestrations by JOHN CAMERON Original London production directed and adapted by TREVOR NUNN and JOHN CAIRD Original London production by CAMERON MACKINTOSH and THE ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY School Edition specially adapted and licensed by MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL and CAMERON MACKINTOSH March 31, 2006 at 7:30pm April 1, 2006 at 7:30pm April 2, 2006 at 2:00pm CAST OF CHARACTERS (In Order of Appearance) Javert.......................................................................................................................... .....David TomczakO Jean Valjean........................................................................................................................Devin ArcherO Bishop of Digne..................................................................................................................... Jason MillerO Constables...............................................................................................Tim Havis, Marshall Bowerman Foreman....... ..............................................................................................................................Zach PaulO Fantine......................... .........................................................................................Brianna SchumacherO Old Woman...........................................................................................................................Kaitlyne -

Tonight/Somewhere from West Side Story Words by Stephen Sondheim/ Music by Leonard Bernstein/Arr

A Few Words About the Rest of the Program: Tonight/Somewhere from West Side Story Words by Stephen Sondheim/ Music by Leonard Bernstein/arr. Terry Winch & Bob Krogstad Set as a mid-century, urban Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story explores the rivalry between two New York street gangs and the forbidden romance that blossoms in spite of it. Bernstein wrote the work in 1957 and it was nominated for 6 Tony Awards that year. If not for The Music Man, it might have won them all. This is the Moment from Jekyll & Hyde Words by Leslie Bricusse/Music by Frank Wildhorn/arr. Bob Krogstad The musical version of the legend of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was premiered in 1997. Frank Wildhorn composed the score and the book was taken from the original Robert Louis Stevenson by Leslie Bricusse. “This is the Moment” comes at the crucial point in the story when Dr. Jekyll is about to test the fateful formula on himself. Into the Fire from The Scarlet Pimpernel Words by Nan Knighthorn/Music by Frank Wildhorn/arr. JAC Redford Also from the pen of Frank Wildhorn and also from the year 1997, The Scarlet Pimpernel depicts the Reign of Terror and the French Revolution. “Into the Fire” comes early in Act I when Percy, Armand and others make plans to rescue some of the doomed aristocrats from the guillotine. The Prayer from Quest for Camelot Words & Music by Carole Bayer-Sager & David Foster/arr. Bob Krogstad Quest for Camelot was an animated feature film from 1998 which was based on the Arthurian novel by Vera Chapman called The King’s Damosel. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Do It Again": Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy's Margins Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4297q61r Author Baltimore, Samuel Dworkin Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Do It Again”: Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy’s Margins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Samuel Dworkin Baltimore 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Do It Again”: Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy’s Margins by Samuel Dworkin Baltimore Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Raymond Knapp, Chair This dissertation examines the ways that various subcultural audiences define themselves through repeated interaction with musical comedy. By foregrounding the role of the audience in creating meaning and by minimizing the “show” as a coherent work, I reconnect musicals to their roots in comedy by way of Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories of carnival and reduced laughter. The audiences I study are kids, queers, and collectors, an alliterative set of people whose gender identities and expressions all depart from or fall outside of the normative binary. Focusing on these audiences, whose musical comedy fandom is widely acknowledged but little studied, I follow Raymond Knapp and Stacy Wolf to demonstrate that musical comedy provides a forum for identity formation especially for these problematically gendered audiences. ii The dissertation of Samuel Dworkin Baltimore is approved. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® ® HOLLYWOODTHEATRE PANTAGES NAME THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 03-277.16-8.11 Charlie Miss Cover.indd Saigon Pantages.indd 1 1 7/2/193/6/19 10:05 3:15 PMAM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE CAMERON MACKINTOSH PRESENTS BOUBLIL & SCHÖNBERG’S Starring RED CONCEPCIÓN EMILY BAUTISTA ANTHONY FESTA and STACIE BONO J.DAUGHTRY JINWOO JUNG at certain performances EYMARD CABLING plays the role The Engineer and MYRA MOLLOY plays the role of Kim. Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by RICHARD MALTBY, JR. & ALAIN BOUBLIL Adapted from the Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL Additional lyrics by MICHAEL MAHLER Orchestrations by WILLIAM DAVID BROHN Musical Supervision by STEPHEN BROOKER Lighting Designed by BRUNO POET Projections by LUKE HALLS Sound Designed by MICK POTTER Costumes Designed by ANDREANE NEOFITOU Design Concept by ADRIAN VAUX Production Designed by TOTIE DRIVER & MATT KINLEY Additional Choreography by GEOFFREY GARRATT Musical Staging and Choreography by BOB AVIAN Directed by LAURENCE CONNOR For MISS SAIGON National Tour Casting by General Management TARA RUBIN CASTING GREGORY VANDER PLOEG MERRI SUGARMAN, CSA & CLAIRE BURKE, CSA for Gentry & Associates Executive Producers Executive Producer NICHOLAS ALLOTT & SETH SKLAR-HEYN SETH WENIG for Cameron Mackintosh Inc. for NETworks Presentations Associate Sound Designer Associate Costume Designer Associate Lighting Designers Associate Set Designer ADAM FISHER DARYL A. STONE WARREN LETTON & JOHN VIESTA CHRISTINE PETERS Resident Director Music Director Musical Supervisor Associate Choreographer Associate Director RYAN EMMONS WILL CURRY JAMES MOORE JESSE ROBB SETH SKLAR-HEYN A CAMERON MACKINTOSH and NETWORKS Presentation 4 PLAYBILL 7.16-8.11 Miss Saigon Pantages.indd 2 7/2/19 10:05 AM CAST (in order of appearance) ACT I SAIGON—1975 The Engineer ...................................................................................................RED CONCEPCIÓN Kim .................................................................................................................. -

Josh Groban Tolkar Vår Tids Största Musikallåtar På Nya Albumet Stages

2015-03-11 15:34 CET Josh Groban tolkar vår tids största musikallåtar på nya albumet Stages Platinasäljande världsstjärnan Josh Groban släpper nytt album med titeln Stages den 28 april via Reprise Records. Albumet är en samling med Grobans återgivningar av några av de största musikallåtarna genom tiderna. “Nothing has inspired me more in my life than the energy that is shared in a theater when great songs and great art are on the stage. I wanted this album to pay tribute to those inspirations and memories.” berättar Groban. Albumet är producerat av Humberto Gatica och Bernie Herms och spelades till stor del in i London’s legendariska Abbey Road Studios tillsammans med en orkester om 75 personer. “Stages is an album I’ve wanted to make since I signed to Reprise/Warner Bros. Records during my freshman year as a Musical Theater student at Carnegie Mellon. I knew in my heart that, at some point, I would visit the songs I love from that world as an album. Having lived in New York City the last few years, seeing as much theater as I could see, and having so many great friends in the theater community, it became really inspiring to take this on. It was time.” - Josh Groban. Se albumtrailern till Stageshär. Tracklist • Pure Imagination (Willy Wonka / Charlie & The Chocolate Factory) Written by: Leslie Bricusse & Anthony Newley • What I Did For Love (A Chorus Line) Written by: Marvin Hamlisch & Edward Kleban • Bring Him Home (Les Misérables) Written by: Alain Boublil, Herbert Kretzmer & Claude-Michel Schonbert • Le Temps Des Cathedrals (Notre-Dame de Paris) Written by: Riccardo Cocciante & Luc Plamondon • All I Ask Of You (duet with Kelly Clarkson) (The Phantom Of The Opera) Written by: Andrew Lloyd-Webber, Elliot Hart & Zachary Stilgoe • Try To Remember (The Fantasticks) Written by: Tom Jones & Harvey Schmidt • Over The Rainbow (The Wizard Of Oz) Written by: Harold Arlen & E.Y.