City of Rocks National Reserve GMP EA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W 114°20'0"W PISTOL LAKE " CHINOOK MOUNTAIN ARTILLERY DOME SLIDEROCK RIDGE FALCONBERRY PEAK ROCK CREEK SHELDON PEAK Red Butte "Grouse Creek Peak WHITE GOAWTh iMte OVaUlleNyT MAoIuNntain LITTLE SOLDIER MOUNTAIN N FD " N FD 6 8 8 T d Parker Mountain 6 Greyhound Mountain r R a k i e " " 5 2 l e 0 1 0 r 0 0 il 1 C l i a 1 n r o Big Soldier Mountain a o e pi r n Morehead Mountain T Pinyon Peak L White MoSunletain g Deer Rd " T " HONEYMOON LAKE " " BIG SOLDIER MOUNTAIN SOLDIER CREEK GREYHOUND MOUNTAIN PINYON PEAK CASTO SHERMAN PEAK CHALLIS CREEK LAKES TWIN PEAKS PATS CREEK Lo FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS o n Sherman Peak C Mayfield Peak Corkscrew Mountain r " d e " " R ek ls R l d a Mosquito Flat Reservoir F r e Langer Peak rl g T g k a Ruffneck Peak " ac d D P R d " k R Blue Bunch Mo"untain d e M e k R ill C r e Bear Valley Mountain k e e htmile r " e ig C r E C en r C re d ave Estes Mountain e G ar B e k " R BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN d CAPE HORN LAKES LANGER PEAK KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN l Forest CUSTER ELEVENMILE CREEK BAYHORRSaEm sLhAorKn EMountaiBn AYHORSE Nat De Rd Keysto"ne Mountain velop Road 579 d R " Cabin Creek Peak Red Mountain rk Cape Horn MounCtaaipne Horn Lake #1 o Bay d " Bald Mountain F hors R " " e e Cr 2 d e eek 8 R " nk Rd 5 in Ya d a a nt o ou Lucky B R S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N Fo S p M y o 1 C d Bachelor Mountain R q l " u e 2 5 a e d v y 19 p R Bonanza Peak a B"ald Mountain e d e w Nf 045 D w R R N t " s H s H C d " e sf r e o Basin Butte r 0 t U ' o r e F a n e 0 l t 21 t -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Boise Caldwell Nampa Idaho Falls Pocatello Twin Falls

d R t y S e s h t m 4 a N R N ver Rd Old Spiral awai Riv n Ri 95 W Hanley Av Waw er Dow '( Hwy d R d Rd -.128 12 r R e Coeur d’Alene Lewiston y Snake River '(95 t se et 0 0.5 1.0 mi d u 0 1 2 mi R 95 m '( H a y s y R a a Wawaw l N l ai River l Nez Perce County Lewiston Rd t n e N A e B Levee t Historical Society Museum Clearwater River N o D St Park 12 3A o '( Rd E Margaret Av t ill S K l Bridge St S Pioneer D d M o ik ll R 6 e i y c 12 h 12 t B 52 t M a t Park yp a '(+,2 S Kiwanis S 5 ass ,+ n P l 5 +, W t Coeur d'Alene a r h o t t t Bridge S n Park M S t BRITISH COLUMBIA o 9 a Lapwai Rd S s n i n n Memorial i Golf Club g h v S p a t t Ramsey e t a i M h A e S Elm t St 6 D City m t r c Park 5 h t Magrath n e a t 1 7th Av r t A v Hall t Pakowki o 8 i P.O. Locomotive e 4 S v S N 1 St. Mary v R +, G 3 3 Clarkson +, h 36 41 o Lake Lewis-Clark h t Park +, +, e t 879 G ALBERTA 3 d Reservoir k -. -

Sage Notes September 2010

September 2010 SAGE NOTES A Publication of the Idaho Native Plant Society Vol. 32 (3) 2010 Annual Meeting: Friends, Field Trips, Fire, and Fun By Janet Campbell, Patricia Hine, Nancy Miller, Nancy Sprague & Helen Yost Along with their families and friends, over 55 members attended the successful 2010 Annual Meeting of the Idaho Native Plant Society (INPS), held this year at Heyburn State Park, near Plummer, Idaho, on Friday, June 11, through Sunday, June 13. Several participants arrived on Thursday to enjoy the deep forests and quiet waters of the reserved campground on Lake Chatcolet, while many members enthusiastically converged with their colleagues from across the state by Friday evening. Most members stayed through Sunday evening or Monday morning, participating in a dozen activities hosted by the White Pine Chapter. All of us who experienced this exuberant, sunny weekend together will remember the gathering as a bright spot in our shared quest to better understand and appreciate the bountiful natural wonders of Idaho and the good people who know and love its botanical treasures. A white form of scarlet gilia (Ipomopsis We all owe a debt of gratitude to the knowledgeable field trip leaders and aggregata) found in McCroskey State diligent Annual Meeting Committee, who so graciously and effectively Park (Nancy Miller photo) organized, hosted, and guided this event. Our sincere thanks go to Pam Brunsfeld, Kathy Hutton, Emily Poor, and Bill Rember for their In this Issue understanding of area lands and generous leadership of field -

Northern Rocky Mountain Exotic Plant Management Team FY 2013 Report

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Biological Resource Management Division Northern Rocky Mountain Exotic Plant Management Team Partner Parks: Bear Paw Battlefield, Big Hole NB, Bighorn Canyon NRA, City of Rocks NR, Craters of Moon NM&R, Dinosaur NM, Fossil Butte NM, Glacier NP, Golden Spike NHS, Grand Teton NP, Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS, Hagerman Fossil Beds NM, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial PKWY, Little Bighorn Battlefield NM, Minidoka NHS, Rocky Mountain NP, Yellowstone NP NRM EPMT 2013 Report Northern Rocky Mountain Exotic Plant Management Team FY 2013 Report Table of Contents PROGRAM SUMMARY SPECIAL and/or COOPERATIVE PROJECTS STAFFING SUMMARY PARK REPORTS BIGHORN CANYON NATIONAL RECREATION AREA CITY OF ROCKS NATIONAL RESERVE CRATERS OF THE MOON NATIONAL MONUMENT AND PRESERVE DINOSAUR NATIONAL MONUMENT FOSSIL BUTTE NATIONAL MONUMENT GLACIER NATIONAL PARK GOLDEN SPIKE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER MEMORIAL PARKWAY GRANT-KOHRS RANCH NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE HAGERMAN FOSSIL BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT MINIDOKA NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE NEZ PERCE NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK BEAR PAW BATTLEFIELD BIG HOLE NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK APCAM 6.4 DEFINITIONS for ACRES for NRM EPMT HERBICIDE USE TABLES NRM EPMT 2013 FINANCIAL REPORT FY2013 Craters of the Moon - Dyer’s Woad Project Hagermann Fossil Beds - Fire Recovery Project Base Funds 2 NRM EPMT 2013 Report In-Kind Contributions PROGRAM SUMMARY The 17 partner parks served by the Northern Rocky Mountain Exotic Plant Management Team (EPMT or Team) consist of more than 4.5 million acres spread across five states (Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming) and two NPS regions (Intermountain and Pacific West). -

Boreal Owl (Aegolius Funereus) Surveys on the Sawtooth and Boise

BOREAL OWL (Aeqolius funereus) SURVEYS ON THE SAWTOOTH AND BOISE NATIONAL FORESTS BY Craig Groves Natural Heritage Section Nongame Wildlife and Endangered Species Program Bureau of Wildlife July 1988 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 S. Walnut St. Bow 25 Boise ID 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost Share Project Sawtooth and Boise National Forests Idaho Department of Fish and Game Purchase Order Nos. 43-0261-8-663 (BNF) 40-0270-8-13 (SNP) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................... Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 Methods .................................................................................................................................2 Results and Discussion ..........................................................................................................6 Management Considerations ...............................................................................................13 Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................................15 Literature Cited ...................................................................................................................16 Appendix A .........................................................................................................................17 -

§¨¦86 §¨¦84 §¨¦84 §¨¦84

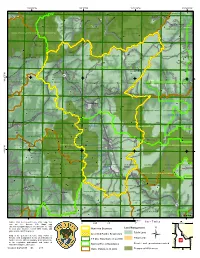

114°0'0"W 113°40'0"W 113°20'0"W N " 0 ' Cinder Butte 0 4 ° " 2 4 EDEN NE BURLEY NW BURLEY NE RUPERT NW ACEQUIA LAKE WALCOTT WEST LAKE WALCOTT EAST GIFFORD SPRING (!Rupert RQ25 RQ25 86 RQ27 RQ24 ¨¦§ 84 ¨¦§ 84 Heyburn RUPERT SE ¨¦§ LAKE WALCOTT SW LAKE WALCOTT SE NORTH CHAPIN MOUNTAIN " MILNER BURLEY SW BURLEY !( RUPERT Burley (! RQ27 RQ81 North Chapin Mountain Horse Butte " " Burley Butte ¤£30 " Milner Butte South Chapin Mountain " " MILNER BUTTE BURLEY BUTTE KENYON VIEW ALBION IDAHOME MALTA NE SOUTH CHAPIN MOUNTAIN Albion !( ¨¦§84 N " RQ77 0 ' 0 2 ° 2 4 BUCKHORN CANYON MARION MARION SE MOUNT HARRISON CONNOR RIDGE NIBBS CREEK MALTA SUBLETT S A W T O O T H N F !( Oakley Red Rock Mountain " Independence Mountain Cache Peak " SANDROCK CANYON SEVERE SPRING OAKLEY BASIN CACHE PEAK" ELBA KANE CANYON BRIDGE Thunder Mountain She"ep Mountain " Graham Peak Black Pine Peak " " War Eagle Peak " Lbex Peak Almo "Ibex Peak !( Smoky Mountain " CHOKECHERRY CANYON NAF STREVELL IBEX PEAK BLUE HILL LYMAN PASS ALMO JIM SAGE CANYON "Middle Mountain Round Mountain " N " 0 ' 0 ° 2 4 A D A KELTON PASS STANDROD ROSEVERE POINT NILE SPRING POLE CREEK COTTON THOMAS BASIN BUCK HOLLOW YOST V E N U T A H Miles 1 in = 7 miles NOTE: This is a georeference PDF map. You 0 3.5 7 14 CANADA can use the Avenza PDF Maps app N O T (avenza.com/pdf-maps) to interact with the map G N Hunt Area Boundary Land Management I to view your location, record GPS tracks, add H S placemarks, and find places. -

Idaho Room Books by Date

Boise Public Library - Idaho Room Books 2020 Trails of the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness Fuller, Margaret, 1935- 2020 Skiing Sun Valley : a history from Union Pacific to the Holdings Lundin John W. 2020 Sky Ranch : living on a remote ranch in Idaho Phelps, Bobbi, author. 2020 Tales and tails : a story runs through it : anthologies and previously Kleffner, Flip, author. 2020 little known fishing facts Symbols signs and songs Just, Rick, author. 2020 Sun Valley, Ketchum, and the Wood River Valley Lundin, John W. 2020 Anything Will Be Easy after This : A Western Identity Crisis Maile, Bethany, author. 2020 The Boise bucket list : 101 ways to explore the City of Trees DeJesus, Diana C, author. 2020 An eye for injustice : Robert C. Sims and Minidoka 2020 Betty the Washwoman : 2021 calendar. 2020 Best easy day hikes, Boise Bartley, Natalie L. 2020 The Castlewood Laboratory at Libuyu School : a team joins together O'Hara, Rich, author. 2020 Apple : writers in the attic Writers in the Attic (Contest) (2020), 2020 author. The flows : hidden wonders of Craters of the Moon National Boe, Roger, photographer. 2020 Monument and Preserve Educating : a memoir Westover, LaRee, author. 2020 Ghosts of Coeur d'Alene and the Silver Valley Cuyle, Deborah. 2020 Eat what we sow cook book 2020 5 kids on wild trails : a memoir Fuller, Margaret, 1935- 2020 Good time girls of the Rocky Mountains : a red-light history of Collins, Jan MacKell, 1962- 2020 Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming 100 Treasure Valley pollinator plants. 2020 A hundred little pieces on the end of the world Rember, John, author. -

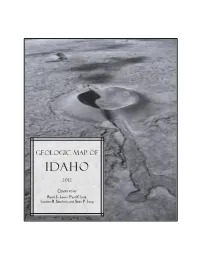

Geologic Map of IDAHO

Geologic Map of IDAHO 2012 COMPILED BY Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Geologic Map of Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Idaho Geological Survey Geologic Map 9 Third Floor, Morrill Hall 2012 University of Idaho Front cover photo: Oblique aerial Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 view of Sand Butte, a maar crater, northeast of Richfield, Lincoln County. Photograph Ronald Greeley. Geologic Map Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long 2012 INTRODUCTION The Geologic Map of Idaho brings together the ex- Map units from the various sources were condensed tensive mapping and associated research released since to 74 units statewide, and major faults were identified. the previous statewide compilation by Bond (1978). The Compilation was at 1:500,000 scale. R.S. Lewis com- geology is compiled from more than ninety map sources piled the northern and western parts of the state. P.K. (Figure 1). Mapping from the 1980s includes work from Link initially compiled the eastern and southeastern the U.S. Geological Survey Conterminous U.S. Mineral parts and was later assisted by S.P. Long. County geo- Appraisal Program (Worl and others, 1991; Fisher and logic maps were derived from this compilation for the others, 1992). Mapping from the 1990s includes work Digital Atlas of Idaho (Link and Lewis, 2002). Follow- by the U.S. Geological Survey during mineral assess- ments of the Payette and Salmon National forests (Ev- ing the county map project, the statewide compilation ans and Green, 2003; Lund, 2004). -

Payette National Forest

Appendix 2 Proposed Forest Plan Amendments Sawtooth National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan Chapter III Sawtooth WCS Appendix 2 Chapter III. Management Direction Table of Contents Management Direction......................................................................................................... III-1 Forest-Wide Management Direction ................................................................................ III-1 Threatened, Endangered, Proposed, and Candidate Species ....................................... III-1 Air Quality and Smoke Management .......................................................................... III-4 Wildlife Resources ....................................................................................................... III-5 Vegetation .................................................................................................................... III-9 Non-native Plants ....................................................................................................... III-13 Fire Management ....................................................................................................... III-14 Timberland Resources ............................................................................................... III-16 Rangeland Resources ................................................................................................. III-17 Minerals and Geology Resources .............................................................................. III-18 Lands and Special -

Baseline and Stewardship Monitoring on Sawtooth National Forest Research Natural Areas

Baseline and stewardship monitoring on Sawtooth National Forest Research Natural Areas Steven K. Rust and Jennifer J. Miller April 2003 Idaho Conservation Data Center Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Steven M. Huffaker, Director Prepared for: USDA Forest Service Sawtooth National Forest ii Table of Contents Introduction ............................................... 1 Study Area ............................................... 1 Methods ................................................. 4 Results .................................................. 5 Recommendations and Conclusions .......................... 12 Literature Cited ........................................... 14 List of Figures ............................................ 16 List of Tables ............................................ 26 Appendix A .............................................. 35 Appendix B .............................................. 36 Appendix C .............................................. 61 iii iv Introduction Research natural areas are part of a national network of ecological areas designated in perpetuity for research and education and to maintain biological diversity on National Forest System lands. Seven research natural areas occur on Sawtooth National Forest: Basin Gulch, Mount Harrison, Pole Canyon, Pole Creek Exclosure, Redfish Lake Moraine, Sawtooth Valley Peatlands, and Trapper Creek (Figure 1). These natural areas were established in the late 1980s and mid 1990s to provide representation of a diverse -

By David M. Miller Open-File Report 81-463 This Report Is Preliminary

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROPOSED CORRELATION OF AN ALLOCHTHONOUS QUARTZITE SEQUENCE IN THE ALBION MOUNTAINS, IDAHO, WITH PROTEROZOIC Z AND LOWER CAMBRIAN STRATA OF THE PILOT RANGE, UTAH AND NEVADA by David M. Miller Open-File Report 81-463 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. ABSTRACT A thick sequence of quartzite and schist exposed on Mount Harrison in the Albion Mountains, Idaho, is described and tentatively correlated with the upper part of Proterozoic Z McCoy Creek Group and Proterozoic Z and Lower Cambrian Prospect Mountain Quartzite (restricted) in the Pilot Range, Utah and Nevada, on the basis of lithology, thickness, and sedimentary structures. Correlations with early Paleozoic or middle Proterozoic strata exposed in central Idaho are considered to be less probable. Rapid thickness changes and locally thick conglomerates in Unit G of McCoy Creek Group (and its proposed correlatives in the Albion Mountains) indicate that cJepositional environments were variable locally. Environments were more uniform during the deposition of limy shaly and limestone in the top of Unit G and quartz sandstone in subsequent strata. The strata on Mount Harrison identified as Proterozoic Z and Lower Cambrian in this study are part of an overturned, structurally complicated sequence of metasedimentary rocks that lie tec topically on overturned, metamorphosed Ordovician carbonate strata and possible metamorphosed Cambrian shale, suggesting that a typical miogeoclinal sequence (Proterozoic Z to Ordovician) was possibly once present near the Albion Mountains area. Elsewhere in the Albion Mountains and the adjoining Raft River and Grouse Creek Mountains, however, Ordovician carbonate rocks appear to stratigraphically overlie metamorphosed clastic rocks of uncertain age that are dissimilar to miogeoclinal rocks of the region.