Placenarnes of Scottish Origin in Nova Scotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

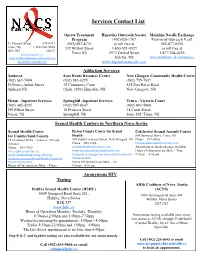

Services Contact List

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

Where to Go for Help – a Resource Guide for Nova Scotia

WHERE TO GO ? FOR HELP A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NOVA SCOTIA WHERE TO GO FOR HELP A Resource Guide for Nova Scotia v 3.0 August 2018 EAST COAST PRISON JUSTICE SOCIETY Provincial Divisions Contents are divided into the following sections: Colchester – East Hants – Cape Breton Cumberland Valley – Yarmouth Antigonish – Pictou – Halifax Guysborough South Shore Contents General Phone Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Crisis Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 HALIFAX Community Supports & Child Care Centres - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Food Banks / Soup Kitchens / Clothing / Furniture - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Resources For Youth - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20 Mental, Sexual And Physical Health - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 22 Legal Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Housing Information - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Shelters / Places To Stay - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Financial Assistance - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 Finding Work - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Education Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 Supportive People In The Community – Hrm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 40 Employers who do not require a criminal record check - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 COLCHESTER – EAST HANTS – CUMBERLAND Community Supports And Child Care Centres -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

Rupert's Land and North-West Territory Order

Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory Order (Order of Her Majesty in Council Admitting Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory into the Union) At the Court at Windsor, the 23rd day of June, 1870 PRESENT, The Queen's Most Excellent Majesty Lord President Lord Privy Seal Lord Chamberlain Mr. Gladstone Whereas by the "Constitution Act, 1867," it was (amongst other things) enacted that it should be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice or Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, on Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, to admit Rupert's Land and the North- Western Territory, or either of them, into the Union on such terms and conditions in each case as should be in the Addresses expressed, and as the Queen should think fit to approve, subject to the provisions of the said Act. And it was further enacted that the provisions of any Order in Council in that behalf should have effect as if they had been enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland: And whereas by an Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, of which Address a copy is contained in the Schedule to this Order annexed, marked A, Her Majesty was prayed, by and with the advice of Her Most Honourable Privy Council, to unite Rupert's Land and the NorthWestern Territory with the Dominion of Canada, and to grant to the Parliament of Canada authority to legislate for their future welfare and good government upon the terms and conditions therein stated. -

Troutquest Guide to Trout Fishing on the Nc500

Version 1.2 anti-clockwise Roger Dowsett, TroutQuest www.troutquest.com Introduction If you are planning a North Coast 500 road trip and want to combine some fly fishing with sightseeing, you are in for a treat. The NC500 route passes over dozens of salmon rivers, and through some of the best wild brown trout fishing country in Europe. In general, the best trout fishing in the region will be found on lochs, as the feeding is generally richer there than in our rivers. Trout fishing on rivers is also less easy to find as most rivers are fished primarily for Atlantic salmon. Scope This guide is intended as an introduction to some of the main trout fishing areas that you may drive through or near, while touring on the NC500 route. For each of these areas, you will find links to further information, but please note, this is not a definitive list of all the trout fishing spots on the NC500. There is even more trout fishing available on the route than described here, particularly in the north and north-west, so if you see somewhere else ‘fishy’ on your trip, please enquire locally. Trout Fishing Areas on the North Coast 500 Route Page | 2 All Content ©TroutQuest 2017 Version 1.2 AC Licences, Permits & Methods The legal season for wild brown trout fishing in the UK runs from 15th March to 6th October, but most trout lochs and rivers in the Northern Highlands do not open until April, and in some cases the beginning of May. There is no close season for stocked rainbow trout fisheries which may be open earlier or later in the year. -

E-News Winter 2019/2020

Winter e-newsletter December 2019 Photos Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Contributions to our newsletters Dates for your Diary & Winter Workparties....2 Borage - Painted Lady foodplant…11-12 are always welcome. Scottish Entomological Gathering 2020 .......3-4 Lunar Yellow Underwing…………….13 Please use the contact details Obituary - David Barbour…………..………….5 Chequered Skipper Survey 2020…..14 below to get in touch! The Bog Squad…………………………………6 If you do not wish to receive our Helping Hands for Butterflies………………….7 newsletter in the future, simply Munching Caterpillars in Scotland………..…..8 reply to this message with the Books for Sale………………………...………..9 word ’unsubscribe’ in the title - thank you. RIC Project Officer - Job Vacancy……………9 Coul Links Update……………………………..10 VC Moth Recorder required for Caithness….10 Contact Details: Butterfly Conservation Scotland t: 01786 447753 Balallan House e: [email protected] Allan Park w: www.butterfly-conservation.org/scotland Stirling FK8 2QG Dates for your Diary Scottish Recorders’ Gathering - Saturday, 14th March 2020 For everyone interested in recording butterflies and moths, our Scottish Recorders’ Gathering will be held at the Battleby Conference Centre, by Perth on Saturday, 14th March 2020. It is an opportunity to meet up with others, hear all the latest butterfly and moth news and gear up for the season to come! All welcome - more details will follow in the New Year! Highland Branch AGM - Saturday, 18th April 2020 Our Highlands & Island Branch will be holding their AGM on Saturday, 18th April in a new venue, Green Drive Hall, 36 Green Drive, Inverness, IV2 4EU. More details will follow on the website in due course. -

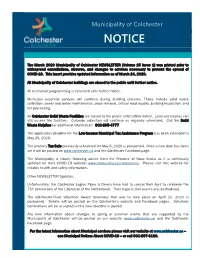

March 2020 Newsletter.Pub

Municipality of Colchester NOTICE The March 2020 Municipality of Colchester NEWSLETTER (Volume 25 Issue 1) was printed prior to widespread cancellations, closures, and changes to services necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This insert provides updated information as of March 24, 2020. All Municipality of Colchester buildings are closed to the public until further notice. All recreation programming is cancelled until further notice. Municipal essential services will continue during building closures. These include solid waste collection, sewer and water maintenance, snow removal, critical road repairs, building inspection, and bill processing. All Colchester Solid Waste Facilities are closed to the public until further notice. Licensed haulers can still access the facilities. Curbside collection will continue as regularly scheduled. Call the Solid Waste Helpline for additional information: 902-895-4777. The application deadline for the Low-Income Municipal Tax Assistance Program has been extended to May 29, 2020. The property Tax Sale previously scheduled for May 5, 2020 is postponed. Once a new date has been set it will be posted on www.colchester.ca and the Colchester Facebook page. The Municipality is closely following advice from the Province of Nova Scotia as it is continually updated on their COVID-19 website: www.novascotia.ca/coronavirus. Please visit this website for reliable health and safety information. Other NEWSLETTER Updates: Unfortunately, the Colchester Legion Pipes & Drums have had to cancel their April to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of the Netherlands. Their hope is that events are rescheduled. The Colchester-Truro Volunteer Award Ceremony that was to take place on April 20, 2020 is postponed. -

Antigonish Floodrisk and Erosion Climate Change Project

Antigonish Floodrisk and Erosion Climate Change Project The study commissioned by the Nova Scotia Department of Regional Economic Development and the Nova Scotia Department of the Environment By Dr. Tim Webster, Katie LeBlanc and Nathan Crowell Applied Geomatics Research Group, Centre of Geographic Science Nova Scotia Community College Middleton, NS B0S 1M0 & Acadia University, Wolfville, NS 1 Executive Summary The Canadian coastlines have been assessed for sensitivity to future sea-level change and it has been determined that the east coast of Canada is highly vulnerable to erosion and flooding. The third assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates that there will be an increase in mean global sea-level from 1990 to 2100 between 0.09 m and 0.88 m (Church et al. 2001). The latest IPCC Assessment Report 4 (AR4) has projected global mean seal-level to rise between 0.18 and 0.59 m from 1990 to 2095 (Meehl et al. 2007). However as Forbes et al. (2009) point out, these projections do not account for the large ice sheets melting and measurements of actual global sea-level rise are higher than the previous predictions of the third assessment report. Rhamstorf et al. (2007) compared observed global sea-level rise to that projected in the third assessment report and found it exceeded the projections and have suggested a rise between 0.5 and 1.4 m from 1990 to 2100. Thus, Forbes et al. (2009) use the upper limit of 1.3 m as a precautionary approach to sea-level rise projections in the Halifax region. -

ROMAN EMPERORS in POPULAR JARGON: SEARCHING for CONTEMPORARY NICKNAMES (1)1 by CHRISTER BRUUN

ROMAN EMPERORS IN POPULAR JARGON: SEARCHING FOR CONTEMPORARY NICKNAMES (1)1 By CHRISTER BRUUN Popular culture and opposite views of the emperor How was the reigning Emperor regarded by his subjects, above all by the common people? As is well known, genuine popular sentiments and feelings in antiquity are not easy to uncover. This is why I shall start with a quote from a recent work by Tessa Watt on English 16th-century 'popular culture': "There are undoubtedly certain sources which can bring us closer to ordinary people as cultural 'creators' rather than as creative 'consumers'. Historians are paying increasing attention to records of slanderous rhymes, skimmingtons and other ritualized protests of festivities which show people using established symbols in a resourceful way.,,2 The ancient historian cannot use the same kind of sources, for instance large numbers of cheap prints, as the early modern historian can. 3 But we should try to identify related forms of 'popular culture'. The question of the Roman Emperor's popularity might appear to be a moot one in some people's view. Someone could argue that in a highly 1 TIlls study contains a reworking of only part of my presentation at the workshop in Rome. For reasons of space, only Part (I) of the material can be presented and discussed here, while Part (IT) (' Imperial Nicknames in the Histaria Augusta') and Part (III) (,Late-antique Imperial Nicknames') will be published separately. These two chapters contain issues different from those discussed here, which makes it feasible to create the di vision. The nicknames in the Histaria Augusta are largely literary inventions (but that work does contain fragments from Marius Maximus' imperial biographies, see now AR. -

Ballot Name; Use of Nickname Section 99.021, Florida Statutes

DE 86-06 - May 1, 1986 Ballot Name; Use of Nickname Section 99.021, Florida Statutes To: Honorable Ann Robinson, Supervisor of Elections, Indian River County, 1840 - 25th Street, Suite N-109, Vero Beach, Florida 32960-3394 Prepared by: Division of Elections This is in response to your request for an advisory opinion pursuant to Section 106.23(2), Florida Statutes, regarding the use by a candidate as defined by the Florida Election Code, Chapters 97-106, Florida Statutes, of his or her proper name or nickname for appearance on the ballot. Section 99.021, Florida Statutes, requires each candidate to include in his or her oath of candidacy the name as the candidate wishes it to appear on the ballot and directs certification of the name by the qualifying officer to the appropriate supervisor of elections so that the name may thus be printed on the ballot. Under common law principles, not abrogated by Florida law, a name consists of one Christian or given name and one surname, patronymic or family name; therefore, the name printed on the ballot ordinarily should be the Christian or given name and surname, 29 C.J.S. Elections §161. In Florida, a person's legal name is his Christian or given name and family surname, Carlton vs. Phalan, 100 Fla. 1164, 131 So. 117 (1930). However, it has been determined that any name by which a candidate is known is sufficient on a ballot, and a person is legally permitted to have printed on the ballot the name which the candidate has adopted and under which he or she transacts private and official business, 29 C.J.S. -

Accessibility Meeting Minutes August 8, 2019 Town Council Chambers

Accessibility Meeting Minutes August 8, 2019 Town Council Chambers Present Deputy Mayor D. MacInnis Mayor L. Boucher Councillor M. Farrell P. Dec, Planner (EDPC) G. Kell G. Mattie Also Present G. Post, Executive Director of the Accessibility Directorate Councilor W. Cormier Councilor A. Murray Councilor D. Roberts J. Lawrence, CAO M. Barkhouse, Director of Corporate Services S. Scannell, Director of Community Development S. Smith, Bylaw Enforcement Officer E. Stephenson, Active Living Coordinator K. Gorman, Marketing and Communication Officer L. Basinger, Strategic Initiatives Coordinator Warden O. McCarron (Antigonish County) Councillor M. MacLellan (Antigonish County) Alex Dunphy, Planner (EDPC) The meeting was called to order at 1:03pm by the Chair, Deputy Mayor D. MacInnis. Mayor L. Boucher introduced Mr. G. Post, Executive Director of the Accessibility Directorate noting his commitment to improving accessibility in the province. Round table introductions took place. G. Post provided a presentation about Access by Design. He noted the Act is about preventing and removing barriers including physical, communication, attitude, institutional, and lack of awareness. A road map is available online for Access by Design, providing guidance on how to make a community accessible by 2030. Those in attendance were advised that the Province has a grant program through Communities Culture and Heritage that will fund up to two thirds of the costs to make businesses more accessible. This funding isn’t just for the built environment but also for things like upgrading business website to accommodate visual impairment, installing hearing aid amplifiers in large meeting rooms, or printing new menus in braille. G. Post noted that there is a requirement for all municipalities to develop an accessibility plan. -

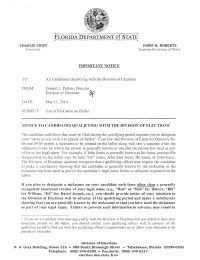

Use of Nickname on Ballot

FLORIDA DEPAR~MENT STATE I . or , CHARLIE CRIST DAWN K. ROBERTS Governor Interim Secretary of State IMPORTANT NOTICE TO: All Candidates Qualifying with the Division of Elections FROM: Donald L. Palmer, Director Division of Elections !If DATE: May 11,2010 SUBJECT: Use of Nickname on Ballot NOTICE TO CANDIDATES QUALIFYING WITH THE DIVISION OF ELECTIONS) The candidate oath form that must be filed during the qualifying period requires you to designate your "name as you wish it to appear on ballot." Case law and Division ofElections Opinions 86 06 and 09-05 permit a nickname to be printed on the ballot along with one's surname when the nickname is one by which the person is generally known or one that the person has used as part of his or her legal name. For example, if John Jones is generally known as Bo Jones, permissible designations on the ballot may be John "Bo" Jones, John (Bo) Jones, Bo Jones, or John Jones. The Division of Elections opinions recognize that a qualifying officer may require the candidate to make a satisfactory showing that the candidate is generally known by the nickname or the nickname has been used as part of the candidate's legal name before a nickname is printed on the ballot. If you plan to designate a nickname on your candidate oath form other than a generally recognized shortened version of your legal name (e.g., "Rob" or "Bob" for Robert, "Bill" for William, "DJ" for David Joseph, etc.), you should provide notice of your intention to the Division of Elections well in advance of the qualifying period and make a satisfactory showing that you are generally known by the nickname or that you have used the nickname as part of your legal name.