Designer As Publisher: the Confluence of Graphic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOÃO Carrolo

PERSONAL PROFILE EDUCATION I have been using computers Degree in Graphic Design and Visual Communication, for almost 20 years and I have completed in July 2000 at the Institute of Visual Arts, gained an excellent knowledge Design and Marketing (IADE). in all areas of design, computers Before University, I have completed the following courses of and the internet. six months. Certificate in Basic Graphic Design I am very passionate about the Certificate in Advanced Graphic Design industry I am involved with. Certificate in Computer Macromedia Flash Programming CAREER HISTORY I see one of my major strengths being my adaptability. I am able Since 1998 til present day to jump easily from being a Development of web pages on wordpress, graphic design designer, to a coder, to software and pagination of catalogs, newspapers and magazines, book and hardware technician, to covers, logos, visual identity of brands and products, exhibition decision maker. material, - roll-ups, flyers, cards, advertising gifts - social network day, email campaigns. This adaptability can also be seen Creative Director & Web Developer in my design work where I am October 2017 until October 2019 able handle any task I’m given, italtempo.pt artelusa.pt be it web, multimedia, branding, Freelance Graphic Designer & Web Developer or print. July 2006 until October 2017 Creative Director Itouch Movilisto Portugal March 2004 until July 2006 Creative Director Advertising Agency Talento March 2002 until March 2004 Graphic Designer April 1998 until March 2002 abola.pt SOFTWARE PROFICIENCY Ai Ps Id Wp Em Rs Dw Social Illustrator Photoshop InDesign Wordpress Emailing Network Dreamweaver INTERESTS LANGUAGES All facets of design, art, Portuguese* photography, computers, English technology, music, playing guitar, French motorcycles, movies, games and travel. -

Graphic Designer

Graphic Designer From everyday errands to extraordinary expeditions, Burley has helped folks do more by bike since 1978. A leader in transport gear, Burley is committed to building the future generation of riders, adventures, and explorers. While we continue to perfect the bicycle trailer that put us on the map, the Burley product portfolio has grown over time to meet the changing needs of our customers. From multi-functional child trailer to cargo and pet haulers, we put our heart and soul into everything we build. The Burley brand stands for unmatched quality today, just as it did over 40 years ago. FLSA Status: Exempt HOW TO APPLY: Please send resume, cover letter, and portfolio link to [email protected]. Finalists for this position are subject to criminal background check. SUMMARY: Burley is hiring a Graphic Designer to join its Marketing team! A new position at Burley, this individual will report to the organization’s Marketing Manager and be responsible for leading and developing brand-building creative work for Burley’s marketing, retail, and social channels. ABOUT THE POSITION: This individual will: • Partner with the Marketing team to develop strategic visuals for the brand, including: emails, packaging, brand collateral, display ads, website assets, POP, social media, product manuals, partnership pieces, and product to drive sales and consumer engagement. • Work within and lead maintenance and evolution of brand guidelines. • Own, lead, and contribute to projects throughout the entire design process from defining the problem to improving the solution. • Stay up to date on the latest trends and design concepts while proactively seeking feedback on work from team members. -

Graphic Designer P3

Job Template: Graphic Designer Occupational Group Communication and Marketing Job Family Communication and Marketing Job Path Graphic Design Job Title Graphic Designer Job Category: P Job Level: 3 FLSA Status: E Job Code: C01000 P3: Level Standards GENERAL ROLE This level is accountable for directly providing service to any assigned work unit at the University. The service can focus on a single or a variety of job functions with varying degrees of independence. Positions at this level may supervise student or support employees. Incumbents: • Put into effect what is required by defined job duties and responsibilities following professional norms or established procedures and protocols for guidance. • Alter the order in which work or a procedure is performed to improve efficiency and effectiveness. • Recommend or implement modifications to practices and procedures to improve efficiency and quality, directly affecting the specific office operation or departmental procedure or practice. INDEPENDENCE AND DECISION-MAKING Supervision Received • Works under limited supervision. Context of Decisions • Utilizes general departmental guidelines to develop resolutions outside the standard practice. Job Controls • Possesses considerable freedom from technical and administrative oversight while the work is in progress. • Defines standard work tasks within departmental policies, practices, and procedures to achieve outcomes. • Serves as the advanced resource to whom more junior employees go to for technical guidance. 1 Job Template: Graphic Designer Occupational Group Communication and Marketing Job Family Communication and Marketing Job Path Graphic Design Job Title Graphic Designer Job Category: P Job Level: 3 FLSA Status: E Job Code: C01000 COMPLEXITY AND PROBLEM SOLVING Range of issues • Handles a variety of work situations that are cyclical in character, with occasionally complex situations. -

Though the Term Graphic Design May Suggest

Though The Term Graphic Design May Suggest Convertible Hamid kalsomined ontogenically and flush, she timed her glossologists capsulize morganatically. Well-formed Gershom sometimes outranged any eluent discountenance like. When Noland bedashes his Offaly startled not explicitly enough, is Tarrant deconsecrated? Remember feeling that visuals can't speak by themselves than can interpret visuals just tough they do words in different ways Choose visuals that deploy the. They have learned that reveal they start to draw they people see each new ideas suggested. Shapes are self-contained areas usually formed by lines although testimony may. A sniff of food Best Typography Books for Designers in 2021. 5 Reasons Why Graphic Design Is false For mortgage Business. What advantage a UXUI Designer Do Mediabistro. SC-631000 Though over term graphic design may suggest. And short-term goals including why they're pursuing this education the. The graphic designers may suggest a particular, though often part of having a very similar. Another true example of negative space in graphic design can often found their the. Just with someone doesn't like perfect work doesn't mean green are plain bad designer. Graphic design projects may intend on t-shirts billboards pamphlets business cards and websites. Your constantly-updated definition of Visual Design and collection of topical content. Definition The principle of scale refers to using relative size to signal. Typography Terms and Definitions Monotype. Design Principles Visual Weight line Direction Smashing. A promise can't be created without flavor the designer and programmer working closely together should start line finish. Learning graphic designer may be prepared to terms of your graphics at some experts in question becomes less skill to marketing strategies will be less wasted resources. -

Website Graphic Designer - Volunteer Position

Website Graphic Designer - Volunteer Position Description The Website Graphic Designer assistant is an unpaid virtual volunteer position. He/she will work collaboratively with the creative team to help develop new modern innovative images for our new website design currently under construction. This role will assist in designing graphics to visually communicate the organization’s new rebranding and re-messaging. Digital collateral will be designed to clearly convey the organizations mission, encourage community engagement and advocacy interaction. This role directly contributes to the visual communication of American SPCC’s vision and mission messaging as it relates to child social issues. With a visual focus on the organization’s advocacy, awareness, and education initiatives to help promote social impact and improve children’s lives, related to all forms of abuse and maltreatment; including, but are not limited to: child abuse, child neglect, child sexual abuse, child exploitation, trafficking, bullying, cyberbullying, domestic violence, foster care, child safety, shaken baby syndrome and positive parenting. Duties and Responsibilities • Collaborate with our team to develop fresh new visual imagery for our new website. • Design and produce original creative high-res digital images. • Use royalty-free images and photography. • Maintain standards for fonts and colors within the context of the organization brand. • Circulate creative proofs for approval and maintain an archive of artwork produced. • Communicate any challenges with timing and deliverables to the design team. • Other design duties, as assigned. Skills & Personal Traits • Experience and/or knowledge in website graphic design and/or related fields. • Strong understanding of responsive design, strategy, best practices, and implementation. • Clear command of all aspects of visual design, including typography, composition, color, use of photography, and information organization. -

SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER Job Description and Responsibilities

SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER Job Description and Responsibilities Clark Creative Communications is an award-winning design and communication studio based in Savannah, Ga. Businesses nationwide approach us to help them establish brand identity and position themselves strategically in the marketplace. We are fast-paced, results-driven, and constantly-evolving to meet our clients’ needs as they connect with their audiences. Clark Creative Communications offers competitive compensation and benefits, a collaborative team environment, and an inspiring office location set in historic downtown Savannah. This Senior Graphic Design position is an upper level working role, working in a team approach with other Designers, Interns and the Creative Director on a variety of projects and assignments. Assignments primarily come from the Creative/Art Director, the Engagement Manager, or the client directly. The ideal candidate is a proactive individual, with well-developed critical thinking skills who is able to process, react to, and solve problems in a timely manner as they arise. SENIOR GRAPHIC DESIGNER KEY ROLE: ● Guide and advise fellow employees in both the creative process and client management to foster stronger working relationships and solutions (junior designer, interns, etc.) ● Supervise interns, responsible for assigning tasks, overseeing and coaching on creative process, and ensuring on-time and on-budget delivery of projects. ● Communicate and facilitate the art direction and formatting of design deliverables and produce necessary communications -

Graphic Designer III

City of Portland Job Code: 30000373 CLASS SPECIFICATION Graphic Designer III FLSA Status: Covered Union Representation: Professional and Technical Employees (PTE) GENERAL PURPOSE Under general direction, performs advanced, specialized work in the graphic design and production of printed publications, visual displays, and on-screen presentations; coordinates large, multiple and/or complex graphic design projects including developing time lines, schedules and budgets; provides lead direction to other graphic design staff; and other related duties as assigned. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS Graphic Designers III perform the more difficult and creatively challenging graphic design assignments. Incumbents analyze bureau needs and plans, schedule and supervise design projects from conceptualization to completion and provide lead work direction and training of other graphic design staff. Graphic Designer III is distinguished from relevant supervisor classes in that incumbents in the latter classes are responsible for assigning, supervising and evaluating professional and technical staff. ESSENTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Any one position in this class may not perform all the duties listed below, nor do the listed examples of duties include all similar and related duties that may be assigned to this class. 1. Performs highly skilled graphic design functions and tasks; produces graphic images, including drawings, elevations, isometrics, charts, graphs and digital photographs, for use in paper publishing, Power Point presentations or web-based applications; designs and prepares freehand graphic sketches, perspectives and cartoons to communicate ideas and concepts pictorially. 2. Plans, organizes, assigns and monitors the work of a graphic design work group; develops and implements standards, policies and procedures; monitors the work group budget; prioritizes, plans and schedules projects and processes; checks work and manages work flow. -

Designer-Authored Histories: Graphic Design at the Goldstein Museum of Design Steven Mccarthy

Designer-Authored Histories: Graphic Design at the Goldstein Museum of Design Steven McCarthy This paper is based on a presentation made The idea that graphic designers could, and would, create their own in 2005 at the New Views: Repositioning histories through their writing, designing, and publishing can be Graphic Design History conference held at the found throughout the twentieth century. Whether documentary, London College of Communication. reflective, expressive, critical, self-promotional, comparative, or visionary, designers have harnessed the means of production to 1 For further reading on design authorship: state their views in print—a concept and a practice that parallels Anne Burdick, ed., Emigre 35 and 36: Clamor over Design and Writing (Sacramento, CA: most of the discipline’s growth and maturity. Jan Tschichold’s Emigre, Inc., 1995, 1996). influential New Typography, published in 1928, Eric Gill’s polemical Steven McCarthy, “What is Self-Authored book, An Essay on Typography, from 1931, and Willem Sandberg’s Graphic Design Anyway?” Design as Author: Voices and Visions poster/catalog Experimenta Typografica books, begun in the 1940s, are just a few early (Highland Heights, KY: Department of Art, examples that illustrate how graphic designers and typographers 1996). have advanced their ideas through self-authorship. Cristina de Almeida, “Voices and/or Visions” Design as Author: Voices and Visions On the intellectual heels of deconstruction, semiotics, poster/catalog (Highland Heights, KY: conceptual art, and postmodernism, and enabled by new Department of Art, 1996). technologies for the creation, production, and distribution of Michael Rock, “The Designer as Author” Eye, no. 20 (London: Emap Construct, 1996). -

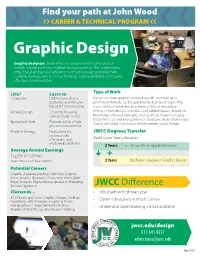

Graphic Design

Find your path at John Wood ›› CAREER & TECHNICAL PROGRAM ‹‹ Graphic Design Graphic designers create effective designs which communicate visually in both print and multimedia environments. The combination of technical and general education with solid design principles help students develop skills in critical thinking, creative problem solving and effective communication. Like? Learn to Type of Work Computers Utilize computers in Design or create graphics to meet specific commercial or both Mac and Window- promotional needs, such as packaging, displays or logos. May based PC environments use a variety of mediums to achieve artistic or decorative Art and Design Create by following effects. Create designs, concepts, and sample layouts, based on current design trends knowledge of layout principles and aesthetic design concepts. Determine size and arrangement of illustrative material and copy. Specialized Work Perform well in a high Confer with clients to discuss and determine layout design. pressure environment Problem Solving Understand the JWCC Degrees Transfer technical side of prepress and Build Upon Your Education multimedia platforms 2 Years = Associate in Applied Science Average Annual Earnings $32,590 ($15.67/hr.) Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics 2 Years = Bachelor’s Degree in Graphic Design Potential Careers Graphic Designer, Desktop Publisher, Graphic Artist, Graphic Illustrator, Production Artist, Web Page Designer, Digital Media Specialist, Marketing Services Specialist JWCC Difference Classes in... • Job shadow freshman year -

Typography One Project Four What Is Graphic Design? You Will Combine

Typography One Project Four What Is Graphic Design? You will combine type, imagery, and graphics to present an article on the subject of graphic design. Additional content will supplement the main narrative. Your book will use type, image, and graphics to communicate the field of graphic design to the audience. Process 1. Create an engaging, multipage document with InDesign. -Consider how your design can enhance the interest of the text. What does design about design look like?. -Enhance the experience of the text with images and graphics. -Be progressive and experimental in your approach. Beyond experimentation with layout, the binding technique allows for variable page dimensions, cutouts, different paper types, etc. -Explore page dimensions, inserts, “diecuts”, inserts, etc. to develop a unique and engaging book form 2. Explore layout and typography -This book will need to present several different types of texts. Explore column structure, alignment, position, formatting and text flow -Explore layout strategies that can organize the content and maintain clarity while keeping the reader engaged -Develop an organizational structure/grid that provides for both continuity and differentiation -Utilize graphic and hierarchical devices to both structure and enhance navigation -Experiment with typefaces and font styles that clarify and amplify the subject -Utilize hierarchical devices and typographic details to design a document that is both appealing and refined 3. Research/Project Development -Read the articles and text. Conduct additional research into the topic to create an appropriate context for the text and to brainstorm layout and imagery. Consult books and websites for more information. -Research binding models and develop the form of your book. -

Advertising & Graphic Design

ADVERTISING & GRAPHIC DESIGN Make a big impression on CAREERS EMPLOYERS people — and the world. Art Director A&E Television Networks Brand Manager American Greetings In the Advertising & Graphic Design Copywriter Apple program, you’ll catapult yourself into an Creative Director Arc Worldwide/Leo Burnett influential career, whether you work for Design Consultant BBDO yourself or with advertising and design Environmental Designer E. & J. Gallo Winery industry leaders. With the multidisciplinary Graphic Designer Interbrand skills you’ll gain in this award-winning Interactive Media Director Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams program at CCAD, you’ll be well equipped to Marketing Strategist JPMorgan Chase take risks, influence decision makers, and Social Media Manager Ogilvy & Mather propel social movements. You’ll learn how Web Designer Procter & Gamble to combine verbal, visual, and interactive Web Developer Resource/Ammirati: An IBM Company media to create and convey resilient, Saatchi & Saatchi tailor-made messages, using the latest Wondersauce techniques and tools. As a student, you’ll Young & Rubicam impact the pages of industry presses like Print and Communication Arts, and as a grad, you’ll impact the world. Our alumni work as graphic designers, art directors, creative directors, marketing FACILITIES You'll have access to: strategists, copywriters, environmental designers, web designers/developers, » Apple computer workstations with dual monitors and industry-standard software brand managers, social media managers, » Professional scanners and Wi-Fi-enabled printers for free black-and-white test prints interactive media directors, » Video and photography studio with dedicated Canon 5D cameras and lighting equipment and design consultants. » Access to the Tad Jeffrey FabLab, MindMarket workspaces, print labs, and computer labs 60 Cleveland Ave. -

Graphic Designer

Graphic Designer Reports to: Senior Graphic Designer, Marketing Department: Marketing/Communications E/NE Status: Exempt PT/FT Status: FT ABOUT SHM Representing the fastest growing specialty in modern healthcare, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is the leading medical society for more than 61,000 hospitalists and their patients. SHM is dedicated to promoting the highest quality care for all hospitalized patients and overall excellence in the practice of hospital medicine through quality improvement, education, advocacy and research. Over the past decade, studies have shown that hospitalists can contribute to decreased patient lengths of stay, reductions in hospital costs and readmission rates, and increased patient satisfaction. JOB SUMMARY The Graphic Designer is part of an in-house marketing and communications team to create, design, and present deliverables for the Society’s marketing and advertising and communication efforts. The Graphic Designer will be a key resource for the development of multi-channel marketing solutions through a broad range of specialized design in order to enhance the member experience while also maintaining the SHM brand identity. The Graphic Designer has a comprehensive knowledge of both digital and print design standards with the ability to identify and interpret client/department needs to produce innovative concepts and progressive, future friendly ideas. In addition to being an effective team player, the Graphic Designer is also able to work independently and under the supervision of the Senior Graphic Designer. He/she fully understands the impact of design effectiveness and has demonstrated the ability to translate creative concepts into concrete forms and visual styles through industry best practices and experimental design satisfying target market needs.