Hockey's Cutting-Edge Canvas – the Art of the Goalie Mask

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1977-78 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1977-78 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Marcel Dionne Goals Leaders 2 Tim Young Assists Leaders 3 Steve Shutt Scoring Leaders 4 Bob Gassoff Penalty Minute Leaders 5 Tom Williams Power Play Goals Leaders 6 Glenn "Chico" Resch Goals Against Average Leaders 7 Peter McNab Game-Winning Goal Leaders 8 Dunc Wilson Shutout Leaders 9 Brian Spencer 10 Denis Potvin Second Team All-Star 11 Nick Fotiu 12 Bob Murray 13 Pete LoPresti 14 J.-Bob Kelly 15 Rick MacLeish 16 Terry Harper 17 Willi Plett RC 18 Peter McNab 19 Wayne Thomas 20 Pierre Bouchard 21 Dennis Maruk 22 Mike Murphy 23 Cesare Maniago 24 Paul Gardner RC 25 Rod Gilbert 26 Orest Kindrachuk 27 Bill Hajt 28 John Davidson 29 Jean-Paul Parise 30 Larry Robinson First Team All-Star 31 Yvon Labre 32 Walt McKechnie 33 Rick Kehoe 34 Randy Holt RC 35 Garry Unger 36 Lou Nanne 37 Dan Bouchard 38 Darryl Sittler 39 Bob Murdoch 40 Jean Ratelle 41 Dave Maloney 42 Danny Gare Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jim Watson 44 Tom Williams 45 Serge Savard 46 Derek Sanderson 47 John Marks 48 Al Cameron RC 49 Dean Talafous 50 Glenn "Chico" Resch 51 Ron Schock 52 Gary Croteau 53 Gerry Meehan 54 Ed Staniowski 55 Phil Esposito 56 Dennis Ververgaert 57 Rick Wilson 58 Jim Lorentz 59 Bobby Schmautz 60 Guy Lapointe Second Team All-Star 61 Ivan Boldirev 62 Bob Nystrom 63 Rick Hampton 64 Jack Valiquette 65 Bernie Parent 66 Dave Burrows 67 Robert "Butch" Goring 68 Checklist 69 Murray Wilson 70 Ed Giacomin 71 Atlanta Flames Team Card 72 Boston Bruins Team Card 73 Buffalo Sabres Team Card 74 Chicago Blackhawks Team Card 75 Cleveland Barons Team Card 76 Colorado Rockies Team Card 77 Detroit Red Wings Team Card 78 Los Angeles Kings Team Card 79 Minnesota North Stars Team Card 80 Montreal Canadiens Team Card 81 New York Islanders Team Card 82 New York Rangers Team Card 83 Philadelphia Flyers Team Card 84 Pittsburgh Penguins Team Card 85 St. -

Sydney Newman, with Contributions by Graeme Burk and a Foreword by Ted Kotcheff

ECW PRESS Fall 2017 ecwpress.com 665 Gerrard Street East General enquiries: [email protected] Toronto, ON M4M 1Y2 Publicity: [email protected] T 416-694-3348 CANADA TABLE OF CONTENTS *HUHKPHU4HUKH.YV\W/LHK6ɉJL FANTASY 664 Annette Street, Toronto, ON M6S 2C8 MUSIC mandagroup.com 1 Bon: The Last Highway 14 Beforelife by Jesse Fink by Randal Graham National Accounts & Ontario Representatives: Joanne Adams, David Farag, TELEVISION YA FANTASY Tim Gain, Jessey Glibbery, Chris Hickey, Peter 2 Head of Drama 15 Scion of the Fox Hill-Field, Anthony Iantorno, Kristina Koski, by Sydney Newman by S.M. Beiko Carey Low, Ryan Muscat, Dave Nadalin, Emily Patry, Nikki Turner, Ellen Warwick 3 A Dream Given Form T 416-516-0911 I`,UZSL`-.\ќL`HUK FICTION [email protected] K. Dale Koontz 16 Malagash by Joey Comeau Quebec & Atlantic Provinces Representative: Jacques Filippi VIDEO GAMES 17 Rose & Poe T 855-626-3222 ext. 244 4 Ain’t No Place for a Hero by Jack Todd QÄSPWWP'THUKHNYV\WJVT by Kaitlin Tremblay 18 Pockets by Stuart Ross Alberta, Saskatchewan & Manitoba Representative: Jean Cichon HUMOUR 5 A Brief History of Oversharing T 403-202-0922 ext. 245 THRILLER by Shawn Hitchins [email protected] 19 The Appraisal by Anna Porter British Columbia NATURE Representatives: 6 The Rights of Nature MYSTERY Iolanda Millar | T 604-662-3511 ext. 246 by David R. Boyd [email protected] 20 Ragged Lake Tracey Bhangu | T 604-662-3511 ext. 247 by Ron Corbett [email protected] BUSINESS 7 Resilience CRIME FICTION Warehouse and Customer Service by Lisa Lisson Jaguar Book Group 21 Zero Avenue 8300 Lawson Road by Dietrich Kalteis SPORTS Milton, ON L9T 0A5 22 Whipped T 905-877-4411 8 Best Canadian by William Deverell Sports Writing Stacey May Fowles 23 April Fool UNITED STATES and Pasha Malla, eds. -

For Immediate Release January 25, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JANUARY 25, 2019 PLAYER ASSIGNMENTS FOR THE 2019 SAP NHL ALL-STAR SKILLS™ 2019 NHL All-Stars to Face Off in Six Individual Events on Friday, Jan. 25 SAN JOSE (Jan. 25, 2019) – The National Hockey League (NHL®) today announced the player assignments for the the 2019 SAP NHL All-Star Skills™. The 2019 NHL All-Stars will compete in six events showcasing their talent tonight at 6 p.m. PT at SAP Center in San Jose, Calif., home of the San Jose Sharks. The 2019 SAP NHL All-Star Skills™ will be televised on NBCSN in the U.S. and on Sportsnet, CBC and TVA Sports in Canada. All six events of the 2019 SAP NHL All-Star Skills™ will be individual competitions, with the winner of each event earning $25,000. Details, rules and participants for all six events of the 2019 SAP NHL All-Star Skills™ are listed below. • Bridgestone NHL Fastest Skater™ • Gatorade NHL Puck Control™ • Ticketmaster NHL Save Streak™ • Enterprise NHL Premier Passer™ • SAP NHL Hardest Shot™ • Honda NHL Accuracy Shooting™ Bridgestone NHL Fastest Skater™ Eight players will compete in the Enterprise NHL Fastest Skater™. Each skater will be timed for one full lap around the rink. The skater may choose the direction of their lap and can be positioned a maximum of three feet behind the start line located on the penalty box side of the center red line. The skater must start on the referee’s whistle and the timing clock will start when the skater crosses the start line. -

Division I Men's Records

Division I Men’s Records Individual Records .................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................. 3 Annual Individual Champions .......... 11 Team Records ........................................... 13 Team Leaders ............................................ 14 Annual Team Champions .................... 21 Polls ............................................................... 22 2 NCAA MEN'S ICE HOCKEY 2014-15 DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2013-14 SEASON Individual Records Official NCAA men’s ice hockey records began ASSISTS PER GAME with the 1947-48 (1948) season and are based Season Miscellaneous on information submitted to the NCAA statistics 2.33—Paul Midghall, Rensselaer, 1959 (49 in 21 games) service by institutions participating in the statis- Career tics rankings. The NCAA began compiling men’s 1.98—Dave Rost, Army, 1974-77 (226 in 114 games) GOALIE WINNING PERCENTAGE ice hockey statistics in the 1995-96 (1996) season. Season From that season on, games against Canadian ASSISTS ON GAME-WINNING GOALS 1.000—Jim Craig, Boston U., 1978 (16-0-0); Brian Cropper, schools are only included in the NCAA team’s sta- Career Cornell, 1970 (29-0-0) tistics if they meet countable opponent require- 24—Marty Sertich, Colorado Col., 2003-06 Career *.944—Ken Dryden, Cornell, 1966-69 (76-4-1) ments. Before 1996, NCAA teams often included POWER-PLAY GOALS *Ties computed as half win, half loss. Must have played in 33% Canadian opponents in their statistics, and are in- Game of team’s minutes. cluded here in season and career records. Game 4—Jay Mazur, Maine vs. UMass Lowell, Feb. 7, 1987; Tom records, however, do not include those versus Ca- Cullity, Vermont vs. Yale, Feb. 3, 1979; Dave Silk, Boston nadian teams. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 9 June 12, 2008 There Being No Objection, the Senate Creating Michigan’S First State Park

June 12, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 9 12491 giving Red Wings fans everywhere the with 27 points, including a remarkable won the Conn Smythe Trophy for the most sweet taste of victory. I immediately six goal effort in the finals, the last of valuable player in the playoffs; called my daughter Erica to share in which proved to be the series clincher. Whereas Nicklas Lidstrom, Kris Draper, her joy as a Red Wing fanatic. Knowing In addition, Captain Nicklas Lidstrom, Kirk Maltby, Tomas Holmstrom, and Darren with his calm demeanor and McCarty have all been members of the team that for her, those last few seemed like for the last 4 Stanley Cups won by the Red an eternity. unshakable nerve, became the first Eu- Wings, and Chris Osgood, Chris Chelios, and This euphoria spilled out into the ropean born player to captain an NHL Brian Rafalski have each earned their third streets of Detroit last Friday, where team to a Stanley Cup championship. Stanley Cup Championship; over a million fans joined the Red The Red Wings continue to set the Whereas Marian and Mike Ilitch, the own- Wings organization in celebration. standard for championship-caliber ers of the Red Wings and community leaders Unfazed by the 92-degree heat, the Red hockey and teamwork. From long-time in Michigan, have once again returned Lord Wings faithful flaunted their red and members of the Red Wings organiza- Stanley’s Cup to the city of Detroit; tion, to veteran additions to the roster, Whereas Red Wings head coach Mike Bab- white, swelling with pride over victori- cock, following in the footsteps of the great ously navigating the difficult path to to new, young talent that helped to en- ergize the team, the 2008 team united Scotty Bowman, has won his first Stanley the cup. -

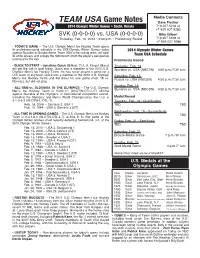

Team USA Game Notes Vs

Game Notes Media Contacts TEAM USA Dave Fischer 2014 Olympic Winter Games • Sochi, Russia 719.207.5216 or +7 925 007 9283 SVK (0-0-0-0) vs. USA (0-0-0-0) Mike Gilbert Thursday, Feb. 13, 2014 • 4:30 p.m. • Preliminary Round 719.207.5196 or +7 925 007 9286 • TODAY’S GAME -- The U.S. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team opens its preliminary-round schedule in the XXII Olympic Winter Games today 2014 Olympic Winter Games against Slovakia at Shayba Arena. Team USA is the visiting team, will wear Team USA Schedule its white jerseys and occupy the right bench (from the player’s perspective looking onto the ice). Preliminary Round • QUICK TO START -- Jonathan Quick (Milford, Ct./L.A. Kings/UMass) Thursday, Feb. 13 will get the call in goal today. Quick was a member of the 2010 U.S. Slovakia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team. He has never played a game for a U.S. team at any level. Quick was a member of the 2010 U.S. Olympic Saturday, Feb. 15 Men’s Ice Hockey Team and did dress for one game (Feb. 18 vs. Russia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. Norway), but did not play. Sunday, Feb. 16 • ALL-TIME vs. SLOVAKIA IN THE OLYMPICS -- The U.S. Olympic Men’s Ice Hockey Team is 0-0-0-1-1 (W-OTW-OTL-L-T) all-time Slovenia vs. USA (NBCSN) 4:30 p.m./7:30 a.m. -

Avalanche 2.7.09

St Louis Volume 4, Issue 27 Game Time February 7, 2009 Four Dollars To Waive Your Doubts The Game Day Guide To St. Louis Blues Hockey Established in 2005 By Brad Lee playing pretty good, I thought my season was starting to come around,” Legace said, referring to his meltdown in Detroit Many Blues fans expected the end of the Manny Legacy era Monday night. “Then to have the carpet pulled out from here in St. Louis was coming quickly. We just didn’t think it underneath you, it’s not a good feeling.” would happen Friday. Here’s the thing that’s not expressed in those words from Twenty-four hours ago the Blues placed their former All-Star Legace. The NHL is a business. And when the team is counting on goaltender on waivers with the intention of demoting him to the a player to stop pucks and win games, patience will wear thin. The Peoria Rivermen. He passed through waivers without a team Blues are under a ton of pressure to show results in order to claiming him and he is now expected to report to Central keep the turnstiles clicking and the beer vendors Illinois on Monday. Looking at Legace’s numbers, pouring. Legace talked about some things during you can see why the Blues made this move. But the interview that hinted at the business of there has been plenty of talk of Legace’s hockey while also saying the right things in attitude around the team in the wake of the order to keep Blues fans sympathetic to him. -

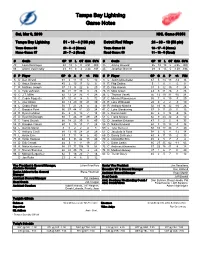

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes Sat, Mar 9, 2019 NHL Game #1051 Tampa Bay Lightning 51 - 13 - 4 (106 pts) Detroit Red Wings 24 - 33 - 10 (58 pts) Team Game: 69 28 - 6 - 2 (Home) Team Game: 68 13 - 17 - 5 (Home) Home Game: 37 23 - 7 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 33 11 - 16 - 5 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 70 Louis Domingue 24 19 5 0 2.91 .908 35 Jimmy Howard 45 18 18 5 2.95 .909 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 43 31 8 4 2.24 .931 45 Jonathan Bernier 29 6 15 5 3.39 .896 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 5 D Dan Girardi 61 4 11 15 5 12 8 L Justin Abdelkader 67 5 13 18 -14 34 6 D Anton Stralman 45 2 15 17 12 8 11 R Filip Zadina 5 1 0 1 -2 0 7 R Mathieu Joseph 57 13 9 22 6 20 17 D Filip Hronek 31 3 12 15 -7 24 9 C Tyler Johnson 66 22 17 39 8 24 25 D Mike Green 43 5 21 26 -1 28 10 C J.T. Miller 62 12 24 36 4 28 26 L Thomas Vanek 56 12 19 31 -10 24 13 C Cedric Paquette 67 10 4 14 5 72 27 C Michael Rasmussen 55 7 8 15 -7 29 17 L Alex Killorn 68 13 20 33 21 39 28 R Luke Witkowski 20 0 2 2 -3 10 18 L Ondrej Palat 50 7 21 28 4 14 39 R Anthony Mantha 52 16 16 32 -10 28 21 C Brayden Point 66 37 44 81 20 24 41 C Luke Glendening 67 9 11 20 0 15 24 R Ryan Callahan 45 6 9 15 7 14 43 L Darren Helm 46 6 8 14 -9 16 27 D Ryan McDonagh 68 7 26 33 29 28 51 C Frans Nielsen 62 9 23 32 -4 12 37 C Yanni Gourde 68 18 21 39 6 49 52 D Jonathan Ericsson 47 3 2 5 -8 35 55 D Braydon Coburn 60 3 15 18 7 24 55 D Niklas Kronwall 64 3 15 18 -3 36 62 L Danick Martel 8 0 2 2 4 8 59 L Tyler Bertuzzi 58 16 17 33 7 30 71 C Anthony Cirelli 68 -

An Educational Experience

INTRODUCTION An Educational Experience In many countries, hockey is just a game, but to Canadians it’s a thread woven into the very fabric of our society. The Hockey Hall of Fame is a museum where participants and builders of the sport are honoured and the history of hockey is preserved. Through the Education Program, students can share in the glory of great moments on the ice that are now part of our Canadian culture. The Hockey Hall of Fame has used components of the sport to support educational core curriculum. The goal of this program is to provide an arena in which students can utilize critical thinking skills and experience hands-on interactive opportunities that will assure a successful and worthwhile field trip to the Hockey Hall of Fame. The contents of this the Education Program are recommended for Grades 6-9. Introduction Contents Curriculum Overview ……………………………………………………….… 2 Questions and Answers .............................................................................. 3 Teacher’s complimentary Voucher ............................................................ 5 Working Committee Members ................................................................... 5 Teacher’s Fieldtrip Checklist ..................................................................... 6 Map............................................................................................................... 6 Evaluation Form……………………............................................................. 7 Pre-visit Activity ....................................................................................... -

Detroit Red Wings Game Notes

Detroit Red Wings Game Notes Thu, Mar 14, 2019 NHL Game #1087 Detroit Red Wings 24 - 36 - 10 (58 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 53 - 13 - 4 (110 pts) Team Game: 71 13 - 17 - 5 (Home) Team Game: 71 29 - 6 - 2 (Home) Home Game: 36 11 - 19 - 5 (Road) Road Game: 34 24 - 7 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 35 Jimmy Howard 46 18 19 5 3.02 .907 70 Louis Domingue 25 20 5 0 2.88 .908 45 Jonathan Bernier 31 6 17 5 3.33 .899 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 44 32 8 4 2.23 .931 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 8 L Justin Abdelkader 70 5 13 18 -14 38 5 D Dan Girardi 61 4 11 15 5 12 11 R Filip Zadina 8 1 1 2 -5 0 6 D Anton Stralman 45 2 15 17 12 8 17 D Filip Hronek 34 3 13 16 -9 28 7 R Mathieu Joseph 59 13 9 22 8 24 25 D Mike Green 43 5 21 26 -1 28 9 C Tyler Johnson 68 24 18 42 10 24 26 L Thomas Vanek 59 14 19 33 -13 26 10 C J.T. Miller 64 12 24 36 5 28 27 C Michael Rasmussen 58 7 8 15 -9 29 13 C Cedric Paquette 69 12 4 16 6 72 28 R Luke Witkowski 22 0 2 2 -3 10 17 L Alex Killorn 70 13 21 34 22 41 39 R Anthony Mantha 55 17 16 33 -13 28 18 L Ondrej Palat 52 8 21 29 5 14 41 C Luke Glendening 70 9 11 20 1 15 21 C Brayden Point 68 37 46 83 23 24 43 L Darren Helm 49 6 8 14 -9 18 24 R Ryan Callahan 46 6 9 15 7 14 51 C Frans Nielsen 65 9 24 33 -8 12 27 D Ryan McDonagh 70 8 28 36 32 28 52 D Jonathan Ericsson 50 3 2 5 -11 35 37 C Yanni Gourde 70 18 23 41 8 49 55 D Niklas Kronwall 67 3 18 21 -5 36 44 D Jan Rutta 25 2 6 8 1 12 56 L Ryan Kuffner - - - - - - 55 D Braydon Coburn 62 3 16 19 8 24 59 L Tyler Bertuzzi 61 16 17 33 -

Goal Prevention 2004 a Review of Goaltending and Team Defense Including a Study of the Quality of �������������’��������������

Goal Prevention 2004 a review of goaltending and team defense including a study of the quality of a hockey ’shots allowed Copyright Alan Ryder 2004 Goal Prevention 2004 Page 2 Introduction I recently completed an assessment of “”in the NHL for the 2002-03 “”season (http://www.HockeyAnalytics.com/Research.htm). That study revealed that the quality of shots allowed varied significantly from team to team and was not well correlated with the number of shots allowed on goal. The consequence of that study was an improved ability to assess the goal prevention performance of teams and their goaltenders. This paper applies the same methods to the analysis of the 2003-04 “”season, focusing more on the results than the method. Shot Quality In summary, the approach used to assess the quality of shots allowed by a team is: 1. Collect, from NHL game event logs, the relevant data on each shot. 2. Analyze the goal probabilities for each shooting circumstance. In my analysis I separated certain “”from “”shots and studied the probability of a goal given the shot type, the ’distance and the on-ice situation (power play vs other). 3. Build a model of goal probabilities that relies on the measured circumstance. 4. Apply the model to the shot data for the defensive team in question for the season. For each shot, determine its goal probability. 5. Determine Expected Goals: EG = the sum of the goal probabilities for each shot. 6. Neutralize the variation in the number of shots on goal by calculating Normalized Expected Goals (NEG) = EG x League Average Shots / Shots 7. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award .................................................................................................